Lecture

When solving practical problems related to random variables, it is often necessary to calculate the probability that a random variable will take a value contained within certain limits, for example, from  before

before  . We will call this event “a hit of a random variable

. We will call this event “a hit of a random variable  on the plot from

on the plot from  before

before  ".

".

Let's agree for definiteness the left end  include in the plot

include in the plot  , and the right one is not included. Then hit a random variable

, and the right one is not included. Then hit a random variable  on the plot

on the plot  equivalent to the fulfillment of inequality:

equivalent to the fulfillment of inequality:

.

.

Express the probability of this event through the distribution function of  . To do this, consider three events:

. To do this, consider three events:

event A is that  ;

;

event B is that  ;

;

event C is that  .

.

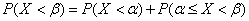

Considering that  , by the addition theorem we have:

, by the addition theorem we have:

,

,

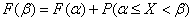

or

,

,

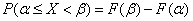

from where

, (5.3.1)

, (5.3.1)

those. the probability of a random variable falling on a given area is equal to the increment of the distribution function in this area.

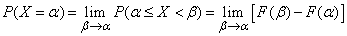

We will unlimitedly reduce the area  believing that

believing that  . In the limit, instead of the probability of hitting the plot, we obtain the probability that the value will take a separately taken value

. In the limit, instead of the probability of hitting the plot, we obtain the probability that the value will take a separately taken value  :

:

. (5.3.2)

. (5.3.2)

The value of this limit depends on whether the function is continuous.  at the point

at the point  or suffers a break. If at

or suffers a break. If at  function

function  has a gap, the limit (5.3.2.) is equal to the value of the function jump

has a gap, the limit (5.3.2.) is equal to the value of the function jump  at the point

at the point  . If the function

. If the function  at the point

at the point  is continuous, then this limit is zero.

is continuous, then this limit is zero.

In the following presentation, we will agree to call "continuous" only those random variables whose distribution function is continuous everywhere. With this in mind, we can formulate the following statement:

The probability of any single value of a continuous random variable is zero.

Let us dwell on this position in somewhat more detail. In this course, we have already met with events whose probabilities were zero: these were impossible events. Now we see that not only impossible, but also possible events can have zero probability. Really an event  consisting in that continuous random variable

consisting in that continuous random variable  will take value

will take value  Perhaps, however, its probability is zero. Such events - possible, but with zero probability - appear only when considering experiments that are not reducible to the scheme of cases.

Perhaps, however, its probability is zero. Such events - possible, but with zero probability - appear only when considering experiments that are not reducible to the scheme of cases.

The notion of an event “possible, but having a zero probability” seems at first glance paradoxical. In fact, it is no more paradoxical than the idea of a body having a certain mass, whereas none of the points inside the body has a definite final mass. An arbitrarily small volume isolated from the body has a certain final mass; this mass approaches zero as the volume decreases and is zero in the limit to the point. Similarly, with a continuous probability distribution, the probability of hitting an arbitrarily small segment may be non-zero, whereas the probability of hitting a strictly defined point is exactly zero.

If an experience is produced in which a continuous random variable  must take one of its possible values, then prior to experience the probability of each of these values is zero; however, in the outcome of the experiment the random variable

must take one of its possible values, then prior to experience the probability of each of these values is zero; however, in the outcome of the experiment the random variable  will certainly take one of its possible values, i.e., one of the events will obviously occur, the probabilities of which were equal to zero.

will certainly take one of its possible values, i.e., one of the events will obviously occur, the probabilities of which were equal to zero.

From what event  has a probability equal to zero, does not follow at all that this event will not appear, i.e. that the frequency of this event is zero. We know that the frequency of an event with a large number of experiments is not equal, but only approaches the probability. From the fact that the probability of an event

has a probability equal to zero, does not follow at all that this event will not appear, i.e. that the frequency of this event is zero. We know that the frequency of an event with a large number of experiments is not equal, but only approaches the probability. From the fact that the probability of an event  is equal to zero, it follows only that with unlimited repetition of experience this event will appear as rarely as desired.

is equal to zero, it follows only that with unlimited repetition of experience this event will appear as rarely as desired.

If an event  in this experience it is possible, but it has a probability equal to zero, then the opposite event

in this experience it is possible, but it has a probability equal to zero, then the opposite event  has a probability equal to one, but unreliable. For continuous random variable

has a probability equal to one, but unreliable. For continuous random variable  at any

at any  event

event  has a probability equal to one, but this event is not reliable. Such an event with unlimited repetition of experience will occur almost always, but not always.

has a probability equal to one, but this event is not reliable. Such an event with unlimited repetition of experience will occur almost always, but not always.

In n ° 5.1, we became acquainted with the “mechanical” interpretation of a discontinuous random variable as a unit mass distribution concentrated in several isolated points on the x-axis. In the case of a continuous random variable, the mechanical interpretation is reduced to the distribution of a unit mass not at individual points, but continuously along the abscissa, and no single point has a finite mass.

Comments

To leave a comment

Probability theory. Mathematical Statistics and Stochastic Analysis

Terms: Probability theory. Mathematical Statistics and Stochastic Analysis