Lecture

In practice, it is often necessary to estimate an unknown probability.  developments

developments  by its frequency

by its frequency  at

at  independent experiences.

independent experiences.

This task is closely related to those considered in the previous ones.  . Indeed, the frequency of the event

. Indeed, the frequency of the event  at

at  independent experiments is nothing more than the arithmetic average of the observed values of

independent experiments is nothing more than the arithmetic average of the observed values of  which in each individual experience takes the value 1 if the event

which in each individual experience takes the value 1 if the event  appeared, and 0, if not appeared:

appeared, and 0, if not appeared:

. (14.5.1)

. (14.5.1)

Recall that the expected value  equally

equally  ; its dispersion

; its dispersion  where

where  . The mathematical expectation of the arithmetic mean is also equal to

. The mathematical expectation of the arithmetic mean is also equal to

(14.5.2)

(14.5.2)

i.e. assessment  for

for  is unbiased.

is unbiased.

Variance of magnitude  equals

equals

. (14.5.3)

. (14.5.3)

It is possible to prove that this variance is minimally possible, i.e.  for

for  is effective.

is effective.

Thus, as a point estimate for an unknown probability  it is reasonable to take frequency in all cases

it is reasonable to take frequency in all cases  . The question arises about the accuracy and reliability of such an assessment, i.e., about building a confidence interval for the probability

. The question arises about the accuracy and reliability of such an assessment, i.e., about building a confidence interval for the probability  .

.

Although this problem is a special case of the previously considered confidence interval problem for mathematical expectation, it is still advisable to solve it separately. The specificity here is that the magnitude  - a discontinuous random variable with only two possible values: 0 and 1. In addition, its expectation

- a discontinuous random variable with only two possible values: 0 and 1. In addition, its expectation  and variance

and variance  linked by functional dependence. This simplifies the task of building a confidence interval.

linked by functional dependence. This simplifies the task of building a confidence interval.

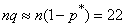

We first consider the simplest case, when the number of experiments  relatively high and the probability

relatively high and the probability  not too big and not too small. Then we can assume that the frequency of the event

not too big and not too small. Then we can assume that the frequency of the event  there is a random variable whose distribution is close to normal. Calculations show that this assumption can be used even for not very large values.

there is a random variable whose distribution is close to normal. Calculations show that this assumption can be used even for not very large values.  : enough for both quantities

: enough for both quantities  and

and  there were more than four. We will assume that these conditions are met and the frequency

there were more than four. We will assume that these conditions are met and the frequency  can be considered distributed according to the normal law. The parameters of this law will be:

can be considered distributed according to the normal law. The parameters of this law will be:

;

;  . (14.5.4)

. (14.5.4)

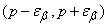

Suppose first that the quantity  we know. Assign confidence probability

we know. Assign confidence probability  and find such an interval

and find such an interval  to value

to value  fell into this interval with probability

fell into this interval with probability  :

:

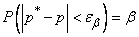

. (14.5.5)

. (14.5.5)

Since the value  distributed normally then

distributed normally then

,

,

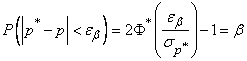

from where as in  14.3,

14.3,

,

,

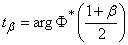

Where  - inverse function of the normal distribution function

- inverse function of the normal distribution function  .

.

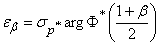

For determining  , As in

, As in  14.3, can be denoted

14.3, can be denoted

.

.

Then

, (14.5.6)

, (14.5.6)

Where  determined from table 14.3.1.

determined from table 14.3.1.

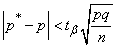

So with probability  it can be argued that

it can be argued that

. (14.5.7)

. (14.5.7)

Actual value  unknown to us; however, inequality (14.5.7) will have the probability

unknown to us; however, inequality (14.5.7) will have the probability  regardless of whether we know or do not know the probability

regardless of whether we know or do not know the probability  . Getting from experience a specific frequency value

. Getting from experience a specific frequency value  , it is possible, using inequality (14.5.7), to find the interval

, it is possible, using inequality (14.5.7), to find the interval  which with probability

which with probability  covers the point

covers the point  . Indeed, we transform this inequality to the form

. Indeed, we transform this inequality to the form

(14.5.8)

(14.5.8)

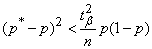

and give it a geometric interpretation. We will postpone the frequency on the x-axis  and the ordinate is the probability

and the ordinate is the probability  (fig. 14.5.1).

(fig. 14.5.1).

Fig. 14.5.1.

Geometric location of points whose coordinates  and

and  satisfy the inequality (14.5.8), will be the inner part of the ellipse passing through the points

satisfy the inequality (14.5.8), will be the inner part of the ellipse passing through the points  and

and  and having tangents at these points parallel to the axis

and having tangents at these points parallel to the axis  . Since the value

. Since the value  there can be neither negative nor greater than one, then the region

there can be neither negative nor greater than one, then the region  corresponding to inequality (14.5.8), it is necessary to restrict left and right straight lines

corresponding to inequality (14.5.8), it is necessary to restrict left and right straight lines  and

and  . Now possible for any value

. Now possible for any value  obtained from experience, build a confidence interval

obtained from experience, build a confidence interval  which with probability

which with probability  will cover an unknown value

will cover an unknown value  . For this we draw through the point

. For this we draw through the point  straight line parallel to the ordinate axis; on this straight border area

straight line parallel to the ordinate axis; on this straight border area  will cut off the confidence interval

will cut off the confidence interval  . Really point

. Really point  with random abscissa

with random abscissa  and non-random (but unknown) ordinate

and non-random (but unknown) ordinate  with probability

with probability  gets inside the ellipse, i.e. spacing

gets inside the ellipse, i.e. spacing  with probability

with probability  will cover the point

will cover the point  .

.

The size and configuration of the “confidence ellipse” depends on the number of experiments.  . The more

. The more  , the more the ellipse is stretched and the narrower the confidence interval.

, the more the ellipse is stretched and the narrower the confidence interval.

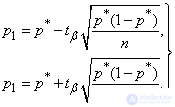

Confidence limits  and

and  can be found from relation (14.5.8), replacing the inequality sign with equality. Solving the resulting quadratic equation with respect to

can be found from relation (14.5.8), replacing the inequality sign with equality. Solving the resulting quadratic equation with respect to  , we get two roots:

, we get two roots:

(14.5.9)

(14.5.9)

Confidence interval for probability  will be

will be

.

.

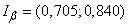

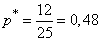

Example 1. Event frequency  in a series of 100 experiments was

in a series of 100 experiments was  . Determine the 90% confidence interval for the probability.

. Determine the 90% confidence interval for the probability.  developments

developments  .

.

Decision. First of all, we check the applicability of the normal law; for this we estimate the values  and

and  . Assuming roughly

. Assuming roughly  get

get

;

;  .

.

Both values are much greater than four; normal law is applicable. From table 14.3.1 for  we find

we find  . By the formulas (14.5.9) we have

. By the formulas (14.5.9) we have

;

;  ;

;  .

.

Note that when increasing  magnitudes

magnitudes  and

and  in formulas (14.5.9) tend to zero; in the limit, the formulas take the form

in formulas (14.5.9) tend to zero; in the limit, the formulas take the form

(14.5.10)

(14.5.10)

These formulas can also be obtained directly by using the approximate method of constructing a confidence interval for the expectation given in  14.3. Formulas (14.5.10) can be used for large

14.3. Formulas (14.5.10) can be used for large  (on the order of hundreds), if only the probability

(on the order of hundreds), if only the probability  not too large and not too small (for example, when both quantities are

not too large and not too small (for example, when both quantities are  and

and  about 10 or more).

about 10 or more).

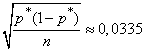

Example 2. Made 200 experiments; event frequency  turned out to be

turned out to be  . Construct an 85% confidence interval for the probability of an event approximately (using formulas (14.5.10)). Compare the result with the exact corresponding formulas (14.5.9).

. Construct an 85% confidence interval for the probability of an event approximately (using formulas (14.5.10)). Compare the result with the exact corresponding formulas (14.5.9).

Decision.  ; according to table 14.3.1 we find

; according to table 14.3.1 we find  . Multiplying it by

. Multiplying it by

,

,

will get

,

,

where do we find the approximate confidence interval

.

.

By the formulas (14.5.9) we find more accurate values.  ;

;  which almost do not differ from the approximate.

which almost do not differ from the approximate.

Above, we considered the question of constructing a confidence interval for the case of a sufficiently large number of experiments where the frequency can be considered normally distributed. With a small number of experiments (and also if the probability  very large or very small) such an assumption cannot be used. In this case, the confidence interval is built based not on the approximate, but on the exact law of frequency distribution. It is easy to verify that this is the binomial distribution discussed in Chapters 3 and 4. Indeed, the number of occurrences of an event

very large or very small) such an assumption cannot be used. In this case, the confidence interval is built based not on the approximate, but on the exact law of frequency distribution. It is easy to verify that this is the binomial distribution discussed in Chapters 3 and 4. Indeed, the number of occurrences of an event  at

at  experiments are distributed according to the binomial law: the probability that an event

experiments are distributed according to the binomial law: the probability that an event  will appear exactly

will appear exactly  times equals

times equals

, (14.5.11)

, (14.5.11)

and frequency  there is nothing more than the number of occurrences of an event divided by the number of experiences.

there is nothing more than the number of occurrences of an event divided by the number of experiences.

Based on this distribution, you can build a confidence interval  similar to the way we built it, based on the normal law for large

similar to the way we built it, based on the normal law for large  (p. 331).

(p. 331).

Suppose first that the probability  we know and find the frequency range

we know and find the frequency range  ,

,  in which with probability

in which with probability  event frequency

event frequency  .

.

For the case of large  we used the normal distribution law and took an interval symmetric with respect to the expectation. The binomial distribution (14.5.11) does not have symmetry. In addition, (due to the fact that the frequency is a discontinuous random variable) of the interval, the probability of hitting it is exactly equal to

we used the normal distribution law and took an interval symmetric with respect to the expectation. The binomial distribution (14.5.11) does not have symmetry. In addition, (due to the fact that the frequency is a discontinuous random variable) of the interval, the probability of hitting it is exactly equal to  may not exist. Therefore, we choose as the interval

may not exist. Therefore, we choose as the interval  ,

,  the smallest interval, the probability of falling to the left of which and to the right of which will be greater

the smallest interval, the probability of falling to the left of which and to the right of which will be greater  .

.

Similar to the way we built the area  for a normal law (fig. 14.5.1), it will be possible for each

for a normal law (fig. 14.5.1), it will be possible for each  and given

and given  construct an area within which the probability value

construct an area within which the probability value  It is compatible with the observed value of the frequency p *.

It is compatible with the observed value of the frequency p *.

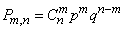

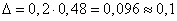

In fig. 14.5.2 shows the curves limiting such areas for different  at confidence level

at confidence level  . The frequency is plotted on the abscissa.

. The frequency is plotted on the abscissa.  , ordinate - probability

, ordinate - probability  . Each pair of curves corresponding to this

. Each pair of curves corresponding to this  , determines the confidence interval of probabilities corresponding to a given frequency value. Strictly speaking, the boundaries of the regions should be stepped (due to frequency discontinuity), but for convenience, they are depicted as smooth curves.

, determines the confidence interval of probabilities corresponding to a given frequency value. Strictly speaking, the boundaries of the regions should be stepped (due to frequency discontinuity), but for convenience, they are depicted as smooth curves.

In order to use such curves to find a confidence interval  The following construction should be performed (see Fig. 14.5.2): the frequency value observed in the experiment should be put off along the abscissa axis

The following construction should be performed (see Fig. 14.5.2): the frequency value observed in the experiment should be put off along the abscissa axis  , draw a straight line through this point parallel to the ordinate axis and mark the points of intersection of the line with a pair of curves corresponding to the given number of experiments

, draw a straight line through this point parallel to the ordinate axis and mark the points of intersection of the line with a pair of curves corresponding to the given number of experiments  ; the projections of these points on the y-axis and give the boundaries

; the projections of these points on the y-axis and give the boundaries  ,

,  confidence interval

confidence interval

Fig. 14.5.2.

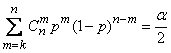

With a given  The curves limiting the "confidence region" are determined by the equations:

The curves limiting the "confidence region" are determined by the equations:

; (14.5.12)

; (14.5.12)

(14.5.13)

(14.5.13)

Where  - the number of occurrences of the event:

- the number of occurrences of the event:

.

.

Solving equation (14.5.12) for  , you can find the lower bound

, you can find the lower bound  “Trust area”; similarly from (14.5.13) you can find

“Trust area”; similarly from (14.5.13) you can find  .

.

In order not to solve these equations anew each time, it is convenient to pre-tabulate (or present graphically) solutions for several typical values of confidence probability.  . For example, in the book of I. V. Dunin-Barkovsky and N. V. Smirnov, "Theory of Probability and Mathematical Statistics in Engineering" there are tables

. For example, in the book of I. V. Dunin-Barkovsky and N. V. Smirnov, "Theory of Probability and Mathematical Statistics in Engineering" there are tables  and

and  for

for  and

and  . From the same book borrowed graph pic. 14.5.2.

. From the same book borrowed graph pic. 14.5.2.

Example 3. Find the confidence limits  and

and  for the probability of an event, if in 50 experiments its frequency was

for the probability of an event, if in 50 experiments its frequency was  . Confidence probability

. Confidence probability  .

.

Decision. By building (see dashed line in Fig. 14.5.2) for  and

and  we find:

we find:  ;

;  .

.

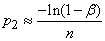

Пользуясь методом доверительных интервалов, можно приближенно решить и другой важный для практики вопрос: каково должно быть число опытов  для того, чтобы с доверительной вероятностью 3 ожидать, что ошибка от замены вероятности частотой не превзойдет заданного значения?

для того, чтобы с доверительной вероятностью 3 ожидать, что ошибка от замены вероятности частотой не превзойдет заданного значения?

При решении подобных задач удобнее не пользоваться непосредственно графиками типа рис. 14.5.2, а перестроить их, представив доверительные границы как функции от числа опытов  .

.

Пример 4. Проведено 25 опытов, в которых событие  произошло 12 раз. Найти ориентировочно число опытов

произошло 12 раз. Найти ориентировочно число опытов  , которое понадобится для того, чтобы с вероятностью

, которое понадобится для того, чтобы с вероятностью  ошибка от замены вероятности частотой не превзошла 20%.

ошибка от замены вероятности частотой не превзошла 20%.

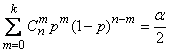

Decision. Определяем предельно допустимую ошибку:

.

.

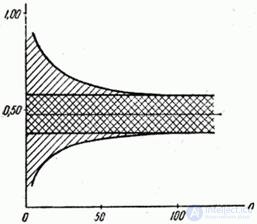

Using the curves in fig. 14.5.2, we will construct a new graph: on the abscissa axis we postpone the number of experiments  , on the ordinate axis - the confidence limits for the probability (Fig. 14.5.3).

, on the ordinate axis - the confidence limits for the probability (Fig. 14.5.3).

Fig. 14.5.3.

The average straight line parallel to the x-axis corresponds to the observed event frequency  .Above and below the straight line are

.Above and below the straight line are  drawn curves.

drawn curves. and

and  depicting lower and upper confidence limits depending on

depicting lower and upper confidence limits depending on  .The area between the curves, which determines the confidence interval, is shaded. In the immediate vicinity of a straight

.The area between the curves, which determines the confidence interval, is shaded. In the immediate vicinity of a straight  double-hatching, a narrower area of 20% permissible error is shown. From fig.14.5.3 it is seen that the error falls to the permissible value when the number of experiments is

double-hatching, a narrower area of 20% permissible error is shown. From fig.14.5.3 it is seen that the error falls to the permissible value when the number of experiments is  about 100

about 100

Note that after performing the required number of experiments, a new verification of the accuracy of determining the probability by frequency may be needed, since in the general case a different frequency value will be obtained that differs from that observed in previous experiments. In this case, it may turn out that the number of experiments is still not enough to ensure the required accuracy, and it will have to be slightly increased. However, the first approximation obtained by the method described above can serve as an indicative preliminary planning of a series of experiments in terms of the time required for them, money costs, etc.

In practice, sometimes you have to meet with a peculiar problem of determining the confidence interval for the probability of an event when the frequency obtained from experience is zero. Such a task is usually associated with experiments in which the probability of the event of interest to us is very small (or, conversely, very high - then the probability of the opposite event is small).

Let, for example, tests of some product on the reliability of work. As a result of testing, the product did not fail once. It is required to find the maximum possible probability of failure.

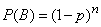

We set this task in a general form. Produced  independent experiments, none of which event

independent experiments, none of which event Did not happen. Confidence level set

Did not happen. Confidence level set  ; требуется построить доверительный интервал для вероятности

; требуется построить доверительный интервал для вероятности  события

события  , точнее - найти его верхнюю границу

, точнее - найти его верхнюю границу  так как нижняя

так как нижняя  , естественно, равна нулю.

, естественно, равна нулю.

Поставленная задача является частным случаем общей задачи о доверительном интервале для вероятности, но ввиду своих особенностей заслуживает отдельного рассмотрения. Прежде всего, приближенный метод построения доверительного интервала (на основе замены закона распределения частоты нормальным), изложенный в начале данного  , здесь неприменим, так как вероятность

, здесь неприменим, так как вероятность  очень мала. Точный метод построения доверительного интервала на основе биномиального распределения в данном случае применим, но может быть существенно упрощен.

очень мала. Точный метод построения доверительного интервала на основе биномиального распределения в данном случае применим, но может быть существенно упрощен.

We will argue as follows. As a result  опытов наблюдено событие

опытов наблюдено событие  , состоящее в том, что

, состоящее в том, что  не появилось ни разу. Требуется найти максимальное значение

не появилось ни разу. Требуется найти максимальное значение  , которое «совместимо» с наблюденным в опыте событием

, которое «совместимо» с наблюденным в опыте событием  , если считать «несовместимыми» с

, если считать «несовместимыми» с  те значения

те значения  , для которых вероятность события

, для которых вероятность события  меньше, чем

меньше, чем  .

.

Очевидно, для любой вероятности  события

события  вероятность наблюденного события

вероятность наблюденного события  equals

equals

.

.

Полагая  , получим уравнение для

, получим уравнение для  :

:

, (14.5.14)

, (14.5.14)

from where

. (14.5.15)

. (14.5.15)

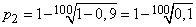

Пример 5. Вероятность  самопроизвольного срабатывания взрывателя при падении снаряда с высоты

самопроизвольного срабатывания взрывателя при падении снаряда с высоты  неизвестна, но предположительно весьма мала. Произведено 100 опытов, в каждом из которых снаряд роняли с высоты

неизвестна, но предположительно весьма мала. Произведено 100 опытов, в каждом из которых снаряд роняли с высоты  , но ни в одном опыте взрыватель не сработал. Определить верхнюю границу

, но ни в одном опыте взрыватель не сработал. Определить верхнюю границу  90%-го доверительного интервала для вероятности

90%-го доверительного интервала для вероятности  .

.

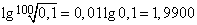

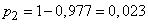

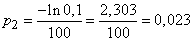

Decision. По формуле (14.5.15)

,

,

;

;

;

;  .

.

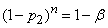

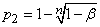

Рассмотрим еще одну задачу, связанную с предыдущей. Event  с малой вероятностью

с малой вероятностью  не наблюдалось в серии из

не наблюдалось в серии из  опытов ни разу. Задана доверительная вероятность

опытов ни разу. Задана доверительная вероятность  . Каково должно быть число опытов

. Каково должно быть число опытов  для того, чтобы верхняя доверительная граница для вероятности события была равна заданному значению

для того, чтобы верхняя доверительная граница для вероятности события была равна заданному значению  ?

?

Решение сразу получается из формулы (14.5.14):

. (14.5.16)

. (14.5.16)

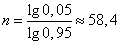

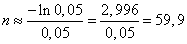

Пример 6. Сколько раз нужно убедиться в безотказной работе изделия для того, чтобы с гарантией 95% утверждать, что в практическом применении оно будет отказывать не более чем в 5% всех случаев?

Decision. По формуле (14.5.16) при  ,

,  we have:

we have:

.

.

Округляя в большую сторону, получим:

.

.

Имея в виду ориентировочный характер всех расчетов подобного рода, можно предложить вместо формул (14.5.15) и (14.5.16) более простые приближенные формулы. Их можно получить, предполагая, что число появлений события  at

at  опытах распределено по закону Пуассона с математическим ожиданием

опытах распределено по закону Пуассона с математическим ожиданием  . Это предположение приближенно справедливо в случае, когда вероятность

. Это предположение приближенно справедливо в случае, когда вероятность  очень мала (см. гл. 5.

очень мала (см. гл. 5.  5.9). Then

5.9). Then

,

,

и вместо формулы (14.5.15) получим:

, (14.5.17)

, (14.5.17)

а вместо формулы (14.5.16)

. (14.5.18)

. (14.5.18)

Example 7. Find an approximate value  for the conditions of example 5.

for the conditions of example 5.

Decision. By the formula (14.5.14) we have:

,

,

i.e. the same result, which is obtained by the exact formula in Example 5.

Example 8. Find an approximate value  for the conditions of example 6.

for the conditions of example 6.

Decision. By the formula (14.5.18) we have:

.

.

Rounding up in a big way, we find  that it differs little from the result

that it differs little from the result  obtained in Example 6.

obtained in Example 6.

Comments

To leave a comment

Probability theory. Mathematical Statistics and Stochastic Analysis

Terms: Probability theory. Mathematical Statistics and Stochastic Analysis