Lecture

By the end of the first year of life, the child utters the first words. “Say: ma-ma! Ma-ma! ”- his parents teach, and finally the moment comes when he repeats:“ Ma-ma! ”Do not think, however, that the child’s learning of speech began only now that he began to repeat your words.

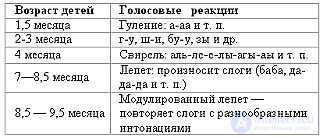

The child begins to train his speech apparatus from the age of one and a half months, making more and more complex sounds and sound combinations, which are called pre-verbal voice reactions. They can distinguish many sounds that will later be elements of articulate speech. But while they can not yet be called the sounds of speech.

All normally developing children have a certain sequence in the development of pre-speech reactions:

Speech is formed from vowels and consonants. Vowels are tonal sounds that are created by vocal cords; in the formation of consonants sounds of the main importance are the noise arising in the cavities of the pharynx, mouth and nose. Such noises occur when air passes through a narrow gap between the tongue and the upper teeth (t, e), between the tongue and the hard palate (g, c), through the gap formed by the close lips (c, t) or teeth (g, c). The sounds produced by the abrupt opening of the lips (b, c) are called explosive. Whisper speech is carried out without the participation of the vocal cords, it consists of only noise sounds. It must be said that whisper speech can be obtained in children only after three years.

Learning the articulation of speech sounds is a very difficult task, and although the child begins to practice sounding from the age of one and a half months, it takes him almost three years to master this art. Walking, flute, babbling, modulated babbling are a kind of game and that is why it gives the child pleasure; he persistently, for many minutes repeats the same sound and, thus, trains in the articulation of the sounds of speech.

Usually, at the first manifestations of walking, the mother or one of the relatives begins to “talk” with the baby, repeating: “ahhhh! a-gu! ”, etc. The kid animatedly picks up these sounds and repeats them. Such mutual imitation contributes to the rapid development of increasingly complex pre-speech reactions when the child begins to utter whole babble monologues. If they do not deal with the child, then the chatter and babbling of it will soon cease.

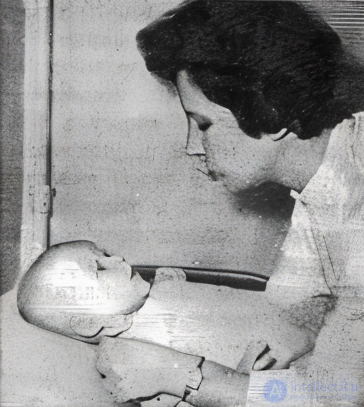

In order for the baby to gulil and babble, it is necessary that he be full, dry and warm, and most importantly, that he has emotional communication with adults. Against the background of joyful revival, all voice reactions become expressive and persistent: children “talk” with various intonations and for a long time 10, 15 minutes in a row. During such a game with a child, it is very important to create conditions so that he can hear himself and the adult. Here, the mother deals with the four-month-old Yura: he utters the sounds “agu-y”, and the mother, after sustaining a small pause of 1–2 seconds, repeats these sounds. Yura animatedly picks them up and says “agu-y” again, etc., every now and then squealing happily. Here the emotional reaction of the adult who plays with the child is very important. If he expresses mimicry and intonation pleasure, joy, when a child imitates sounds, then success will be particularly significant. Already from the first months, the approval of adults is a strong incentive for children.

Preverbal reactions will develop poorly when they are engaged with the child, but he cannot hear himself and the adult. So, if there is loud music in the room, people are talking to each other, or other children are making noise, the child will become silent very soon. All voice reactions of a child who is constantly in a noisy environment develop very late and are very poor in the number of sounds that he learns to articulate. This circumstance especially needs to be borne in mind by those parents who believe that a child from an early age should be accustomed to noise, otherwise, they say, he will be spoiled and will then demand some special conditions, “Our Lucy, you know, not the princess! Why does life have to stop, if she wants to eat or sleep? ”Such a dad says indignantly.

One young father - a big fan of jazz music - constantly turns on the tape recorder, believing that he does this not only for his own pleasure, but also for the proper upbringing of his little daughter: “We don’t have a separate nursery room and are not expected, so the child should get used to sleep and play and when talking and listening to music. Absolutely non-pedagogical to dance to the tune of a child. ” By the way, when adults do or relax themselves, they usually require silence, and Lyusiny “agu-y” and “bu-y” - these are also exercises, and it means that they also require certain conditions. In addition, the immature nervous system of a young child is especially sensitive to the harmful effects of noise. This is not at all pampering - this is only a concern for the proper development of the baby.

There is another condition that is probably known to many, but nevertheless very often not observed - and not only in the family, but also in children's institutions: the child must see the face of the adult who is talking to him well. It is interesting here to tell about the experiments conducted in our laboratory G. S. Lyakh. With several babies at the age of two months, classes were held in the child’s home in which the adult performed articulatory movements in front of the child for 2-3 minutes (as if to make sounds “a”, “y”, etc.), but the sounds did not uttered. The children stared at the adult’s face (Fig. 33 and 34) and very accurately repeated his facial expressions.

Fig. 33. A 2-month-old baby imitates the articulation of the sound "y."

Fig. 34. A 2-month-old baby imitates the articulation of sound “a”.

When the adult began to make sounds, the babies immediately picked them up and reproduced quite accurately. But as soon as the adult covered his face, the imitation of facial expressions and sounds immediately stopped (Fig. 35).

Fig. 35. An adult utters the sounds behind the mask. The kid looks calmly. Identity is not.

Before other children of the same age (second group), an adult uttered the same sounds “a”, “y”, “s”, etc., but his face was covered with a medical mask and was not visible to the child. The children of the second group did not pay attention to the sounds pronounced before them and did not make any attempts to imitate them. Only after they learned to reproduce the sounds uttered by adults, they began to imitate the audible sounds. Thus, it turned out: first, the exact connections between the sound and the corresponding articulatory facial expressions should be worked out, only then the ability to sound imitation, when the child does not see the adult facial expression, appears.

In life, unfortunately, it is constantly observed that they talk with small children at a great distance and do not care that the speaker’s face is clearly visible to the child. “Agu-y, agu-y, Olenka,” says the mother, while she herself leaned over the sewing at that time. Meanwhile, if the baby does not see her mother's articulatory facial expressions, she cannot reproduce the sounds that she utters! That is why 2-3 minutes, fully given to the child, will bring him much more benefit than long conversations between the cases, when the child hears the voice of an adult, but does not see his face - in this case it will be just a noise for the baby.

In the eighth month, children begin to repeat the syllables for several minutes in a row: “yes, yes, yes, yes,” “ta-ta-ta-ta”, etc. It is important to keep in mind that babble is very connected with rhythmic movements: a child rhythmically waving his arms (often knocking with a toy) or jumping, holding onto the railing of the crib (playpen). At the same time, he shouts syllables in the rhythm of movements, and as soon as the movements cease, he stops. Therefore, it is very important to give the child freedom of movement — this contributes not only to the training of his motor skills, but also to the development of “pre-verbal” articulations.

The tactile and muscular sensations received by the child when washing, bathing, feeding are also very significant. The same muscles are involved in chewing and swallowing food as in the articulation of sounds. Therefore, if the baby receives a long time for pureed food and the corresponding muscles do not train, the development of a clear articulation of speech sounds is delayed. Very often, a child who constantly eats chopped meat chops, mashed vegetables, pureed apples, etc., not only in early childhood has a sluggish articulation of sounds, but also preserves it later.

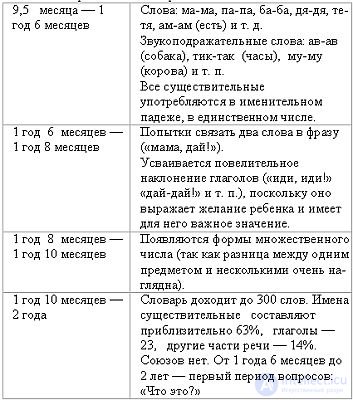

So, at the end of the first year of life, children try to repeat individual words after adults. Girls start talking a little earlier — at the 8th – 9th month, boys — at the 11th – 12th month of life.

A number of domestic linguists studied the development of the speech of children. N. Rybnikov and A. N. Gvozdev did a lot in this regard. Their research has established such a sequence in the development of the child's language.

This is a very concise and dry list of stages in the development of children's speech. Behind each of them is a great work of the child himself and the people around him: it’s not at all easy to learn how to pronounce the words you hear! It is necessary to repeat them correctly after adults - and the reflex of imitation, extremely strongly developed in young children, helps in this - it’s not for nothing that they say about babies: “These are monkeys!”

But it is not enough just to repeat the word - you need to train in its pronunciation. And the child constantly repeats: “Mom-ma! Mom-ma! ”Listening to one-year-old children, we wonder how it does not bother them so many times to repeat the same word ?! Here the children are helped by another reflex - the play. The repeated repetition of syllables and words is a very exciting activity for kids, especially if someone listens to them!

It must be said that the child needs an audience at all stages of speech development, but at the earliest, he cannot do without it at all, and if no one pays attention to the baby, then he becomes silent. That is why adults should approach the child from time to time, talk to him, listen to him and show that they listen with pleasure.

The first words of children have a broad generalized meaning, but these are not the levels of generalization mentioned in the previous chapter, this is a very primitive generalization, arising from the fact that the child still does not clearly distinguish between the objects that he calls this word. The one-year-old Slavik used the word “ko” to designate milk, a cup, a bib. Vera at the same age called “yum-yum” the name of any food and dishes from which she was fed, that is, everything that had food reinforcement for her.

The same words are still the name not only of such an undifferentiated group of objects, but also of the actions that produce them. The same Vera, hungry, shouts: “Yum-yum!”, I.e. “give me some food”; when she saw the child who was eating the cookies, she pointed at him: “Yum-yum!” - “eating”.

The one-year-old Lenochka used the same word “mother” in different situations. The mother leaves the room, and the girl calls her anxiously: “Mom! mother! ”I found a red button on the floor, raised and enthusiastically exclaims, addressing my mother:“ Mom! Mom! ”She fell and whined plaintively:“ Ma-ma-a! ”The word“ mother ”for Lena is not only referring to a specific person, but also designating various actions that the child expects from her mother: come here, look, help me!

Only very gradually do children assimilate different names for all objects and actions. As many psychologists testify, in this process, the manipulation of objects is extremely helpful.

For illustration, we present some of our observations.

At 1 year 3 months, Alyosha used the word “ki” (kitty) to refer to many objects - a cat, a hat, a fur coat, a teddy bear and a monkey, and the word “eye” (window) was associated with a window, a picture, a portrait and a mirror hanging on the wall. With all the objects that were designated by the word "kitty", many actions were performed. Wearing a fur coat before the walk, the child stretched his arms and stuck them in his sleeves, turned his neck when buttoning them, felt the weight of the fur coat on himself, etc. The dressing of the cap was associated with other motor acts. Alyosha stroked the cat many times, tried to grab her, two or three times she scratched him; many times the boy ran after the cat, tried to take her in his arms, here he received a lot of sensations of a completely different character than in actions with a fur coat and a hat. With a plush toy — a bear and a monkey — the child played, taking them in his arms, seated him at the table, put them to sleep, etc. Moreover, each of these actions was associated with a specific word that the adult pronounced. A month later, Alyosha made significant changes in the designation of these items with the words: “ki” began to refer only to the cat, the hat and fur coat began to be called “xia”, and the teddy bear and monkey - “miss.”

The situation with the word “window” was quite different. At 1 year 3 months, and at 1 year 4 months, and at 1 year 5 months, this word still meant a window, a picture, a portrait and a mirror. The child saw objects hanging on the wall, but any active actions with them were impossible for him, and one passive contemplation of these objects, summarized by the child due to their location on the wall (or in the wall), was clearly not enough to distinguish them from each other.

As you can see, in the development of motor speech the same patterns operate as in the development of understanding of words - remember the experiments where children developed 20 visual conditioned reflexes and 20 motor reflexes on a book? .. If the connections were only visual, the word “book” remained the designation of only one subject, and if the connections were motor, the word “book” began to generalize many books. It turns out that in order for the child to begin to call a certain object with the word, actions with this object are necessary.

Many authors who have studied the development of the speech of children indicate that the child first of all begins to name those objects that are more often touched with hands: “spoon”, “cup”, “plate” (“teapot” or “vase” much later); details of objects that he touches with his hands, also stand out earlier (for example, the handle of a cup, and not its bottom).

During the first half of the second year of life, the child learns a large number of names of objects and actions, but they all relate to individual objects so far; they have not yet received a generalized meaning.

In the second half of the second year many important events take place. At this time, the child begins to put two words into a phrase. “Mom, di!” (Mom, go) - said Lyalya at 1 year and 6 months old; “Mom, give it to me!”, - Kate uttered quite clearly at the same age; Igorka's first sentence at 1 year and 8 months was “Baba, Katey!” (woman, swing). This is a very big complication in the activity of the brain: a system of connections has been developed for each word, and now they are being combined. Once started, this process of merging communication systems further develops very rapidly. In the third year of life, children begin to build phrases already in three words, and they all express the desires and needs of the baby: “Tanya, give yum!”, “Victor wants a ghoul!” (Walk).

Another important event occurs in the development of the speech of children about two years old: they discover that everything around has its own name - each, every subject! The child greedily asks: “What is this?”, “And what is this?” - and he finds out that this is a dog, this is a bus, this is a bird, this is a car, etc., etc.

But this soon ceases to satisfy the little ones - they want to continue to know: what is the name of this boy? And that girl? And that dog over there? What about a sparrow that bathes in dust? “What is his name?” They now continuously ask. If you can not satisfy the interest of the child, then he himself will immediately come up with a name.

When she was two and a half years old, Marisha was presented with two live crayfish; she immediately called them: Biha and Micah. Cancers sat dully in a bowl of water, barely moved their whiskers and refused to eat, although they were offered meat and flies, and everything they could think of. Someone brought in as treats for earthworm crayfish. Marisha, of course, first asked what the name of the worm was. While the adults thought how to answer, she herself suggested: “Let him be Zinochka!” (Biha and Miha squeezed back from Zinochka, they didn’t have her, and so that they would not die of hunger, they were let out into the rivulet).

The same girl rode with her grandmother in a tram and all the time asked the question: “What is your son-in-law?” (What is their name?), Showing this to one of the passengers, then to passers-by on the street. Seeing the herring sticking out of the bag of a woman who was standing nearby, Marisha asked about her: “How are they sowing seedlings?”

You see, what a thirst a child has to find new and new designations for each object. He so wants to know more titles - you just tell him! This is what ensures the development of higher degrees of generalization in young children.

If the name is difficult, then very often the baby replaces it with a consonant, easier to articulate. Julia (2 years 6 months) did not always agree to accept the names that adults offered her. So, when she was called the nightstand, Julia frowned and said: “Lutche - Tanechka” - and so she began to call the nightstand; столик у нее был Толик, диван — Ваня и т. д. При этом Юля не просто коверкала слова или пропускала часть трудных для нее звуков, но всегда поясняла: «Лютче так».

At the age of 3, Kolya had trouble pronouncing the sound "r", but he managed to pronounce it correctly in combination with "d" (for example, he pronounced the words "firewood", "bucket", "suddenly", etc. correctly); the boy persuaded his mother: "Let's call everything like this - dryba, droza!" (fish, rose).

In Chapter I, it was already said that a child's assimilation of a sequence of sounds in a word is the result of the development of a system of conditional connections. But the combination of words in a phrase is also based on the development of a system of conditional connections. N. I. Krasnogorsky was the first to point this out (1952). He noted that the combinations of words in a phrase are stereotypes or patterns. A child imitates certain sound combinations from the speech of people around him.

This principle of a stereotype (or pattern) is very clearly visible if you listen carefully to the speech reactions of children. "Galya, what are you putting in your mouth?" — the father angrily asks his three-year-old daughter. “All sorts of nasty things!” — she replies. The girl is often scolded for putting all sorts of nasty things in her mouth, and now she has simply finished the usual phrase, i.e. the learned verbal stereotype.

“Do you want an egg?” — the grandmother asks Lenochka, 2 years old

6 months. “Not a stale one, but a golden one,” says Lena. The word “egg” seems to pull the following ones along: “and not a simple one, but a golden one” — after all, how many times has Lena heard this combination of words!

The mother offers three-year-old Katya half a pie: “Shall we share?” — “We’ll share it cleverly — you get the tops, and I get the carrots!” the daughter replies. The word “share” firmly enters the verbal stereotype, which the girl immediately reproduces.

In all these cases, the same principle of developing a single system of conditional connections is very clearly visible. You touch one link - and the whole system comes into action. Sometimes the same link is part of two stereotypes, and then confusion easily occurs. Roma (3 years 2 months) recites:

A white cat, A gray tail, That's how, that's how, A gray goat!

Here the word "gray" immediately seemed to switch one speech stereotype to another.

Lenya (also 3 years 2 months) tells a fairy tale about a speckled hen. When he got to the words "the grandfather is crying, the grandmother is crying", then he "slid" to another fairy tale: "How can I not cry? The fox got into my house and won't leave!" Here the reason for the jump was the word "crying", which is included in both fairy tales.

Professor A. G. Ivanov-Smolensky also observed in his experiments on conditioned reflexes that if two systems of conditioned stimuli have a common component (component), this creates a kind of "drainage" for the transition of the excitation process from one system to another. Ivanov-Smolensky showed that this phenomenon of excitation "drainage" also occurs in older children, but it no longer manifests itself in slipping from one stereotype to another, but remains in a latent form. We, adults, can observe this phenomenon in ourselves: some sensation evokes not one, but several associations in us. However, we continue to develop one specific thought, inhibiting side ones.

Thus, frequent slippages of thought in children have an understandable physiological cause.

Thus, on the basis of increasingly complex stereotypes, the child's active speech is formed.

We, adults, give children many speech stereotypes that serve as templates for them. But then suddenly we hear:

— Granny, we are giving you three perfumes! — and three-year-old Marisha presents her grandmother with a set of three bottles of perfume — from herself, mom, and dad.

— Did you sew this with a needle? — asks Lesha, 2 years 10 months, when his mom puts a new shirt on him.

— Oh, don’t squeeze the fungus! — shouts Lenochka, 2 years 10 months. She admires: “Look at this flock of blueberries!”

“With a needle,” “blueberries,” “three spirits,” etc. — these are mistakes that are associated with insufficient language acquisition. Some of these mistakes, however, are so common and so regularly repeated in the speech of all normally developing children that they are worth talking about separately.

It is important to know the “patterns” of mistakes in children’s speech in order to understand the process of speech development. In addition, parents and educators should know how to treat children's mistakes.

What are the most typical mistakes and why are they interesting?

With regard to verbs, the most common mistake is constructing verb forms based on one that is easier for the child. For example, all children at a certain age say: I get up, I lick), I chew, etc. "Have you finally chewed it?" - "I'm chewing." - "Well, get up, stop lying around!" - "I get up, I get up!" - "Mom, Leka is licking the glass!"

This form is not invented by the child, because he constantly hears: I break, you break, I fall asleep, you fall asleep, I grab, you grab, I allow, etc., and, of course, it is easier for a child to use one standard verb form. In addition, the articulation of the words "I lick", "I chew" is easier than the words "I lick", "I chew". Therefore, despite the corrections of adults, the child stubbornly speaks in his own way. These mistakes are therefore based on the imitation of a frequently used verb form, but the child changes all other verbs to the model of which. Sometimes such imitation occurs according to the model of the verb form just heard.

"Igor, get up, I've been waking you up for a long time." - "No, I'll sleep a little longer," the three-year-old boy answers.

Four-year-old Masha is spinning around her mother, who has laid down to rest. "Masha, you're bothering me." - "Why are you lying there and lying there?"

Scientists who have studied the development of children's speech have noted that when a child learns one form of linguistic meaning, he then extends it to others. Sometimes this generalization of a linguistic form turns out to be correct, sometimes not. In cases like those given here, such a generalization was incorrect.

In small children, as A. N. Gvozdev points out, the use of the past tense of verbs only in the feminine gender (ending in "a") is very common. "I drank tea", "I went", etc., - boys also say. The reason for this very common mistake is unclear; perhaps it lies in the greater ease of articulation.

Children encounter many difficulties when they begin to change nouns by case. Well, really, why are tables already tables, and chairs are already chairs?! Unable to cope with the complexity of Russian grammar, little children form case endings according to some already learned pattern. "Let's take all the chairs and make a train," three-year-old Zhenya suggests to his friend. "No," he objects, "there aren't enough chairs here." But Gera, aged three years and eight months, has already remembered well that the plural of the word "chair" is "chairs": "I have two chairs in my room, and how many do you have?"

When the instrumental case appears in a child's speech, he forms it for a long time according to a template scheme by adding the ending -ом to the root of a noun, regardless of the gender of the noun: igolkom, koshkom, lozhkom, etc., i.e. according to the pattern of declension of masculine nouns.

Children constantly make mistakes in the gender endings of nouns: "lyudikha" (woman), "tsyplikha" (chicken), "loshidkha" (horse), korov" (bull), "lyud" (person), "kosh" (cat), etc. Four-year-old Seva's father is a doctor, but when he grows up, he himself will be a prac (in his opinion, "prac" is a man-laundress), since he really likes soap foam and bubbles. Three-year-old Lucy, on the contrary, was attracted by the profession of a doctor, and she decided that when she grew up, she would become a “doctor”.

The mistakes that children make in using the comparative degree of adjectives are very typical. In this case, again, the imitation of the previously learned form is clearly manifested. We say: longer, funnier, poorer, more fun, etc. A large number of adjectives have a comparative degree in this form. Is it any wonder that the little ones say: good, bad, higher, shorter, etc.

"You are a good boy!" - "And who is good, me or Glory?" "I'm close to the kindergarten to go." - "No, close to me."

Children without any embarrassment form a comparative degree even from nouns. “And we have pines in the garden!” - “So what? And our garden is still pine! "

All these examples show that typical mistakes in children's speech are related to the fact that grammatical forms are formed according to a few previously learned patterns. This means that classes of words with their corresponding grammatical relations are not yet clearly separated, they are still primitively generalized. Only gradually, when such a division becomes clear, will grammatical forms be subtly distinguished.

Usually adults confine themselves to laughing at the funny distortion of the word. When a child’s mistakes in speech are random (like “three spirits,” “they did not pressure,” etc.), then they really should not fix the attention of the child. The same mistakes that are typical (the formation of the instrumental case with the help of the end of the th, regardless of the gender of the noun, the end of its comparative degree of adjectives, etc.) must be corrected. If you do not pay attention to them, the child’s speech will remain incorrect for a very long time.

In no case can not laugh at the kid or tease him, as is often the case when a boy says “I went” for a long time, “I drank”, etc.

Up to three years, Igor K. persistently used the past tense of verbs only in the feminine gender. To wean him, the grandmother and the nanny began to tease the kid: “Oh, our girl drank tea!”, “You know, Igor is a girl because we have a girl - he says“ took ”,“ fell ”!” The boy took offense, wept and avoided verbs in the past time. “Go drink tea, Igorek!” - “I’ve been drunk already!” - “Did you take the book?” - “No, I don’t take it.” Only in three and a half years, Igor began to gradually use the past tense of verbs correctly.

It is also not necessary to retell children's words and phrases with an error as anecdotes, especially in the presence of the children themselves. Children are very proud of the fact that they managed to make adults laugh, and they begin to distort the words intentionally.

The best thing is to calmly fix the child, without making a bit of a sharpness or cause for offense.

Talking about mistakes leads us to another, very interesting question - about children's word creation. In both of these phenomena, there are quite a few common features both in external manifestations and in the mechanisms of their occurrence.

It is obvious to us that most of the words the child memorizes by imitation: “give-and-let” - the mother addresses her one-year-old son and takes the toy from her hands; “Give-give” - repeats the baby. “Kitty, this is kitty,” an adult shows up to a cat; “Ki-i” is how the child responds.

But if you carefully listen to the children's speech, we will notice a lot of words that the kids seemed unable to borrow from us adults.

- I'm the truth! - declares four-year-old Alyosha.

- Ugh, what a hood! - frowns from the rain three-year Igorek.

- Look, what a bukarashka! - Stasik is moved by three years of five months, looking at the little bug.

Dima, three years and two months, is standing with her father in a zoological garden in front of an open-air cage, in which several birds of different breeds are placed, and then pointing to one, then to another, achieves: “Well, Dad, what is her name?” Dad shrugs and is silent . Then Dima tugs at his sleeve, decisively explains: “That bosha is called a granny, and the little one is a cook. Do you remember? ”And goes on, very pleased that he left behind not some unknown birds, but quite definite ones: a cook and a grandmother.

Mom praised the five-year-old Marina for having thought herself to sweep the floor and wipe the dust: “You have become completely independent!” The girl looked very seriously at her mother and replied: “I’m not only independent, I am self-sufficient and self-certifying!”

The appearance of such "new" words in the speech of children is called word creation.

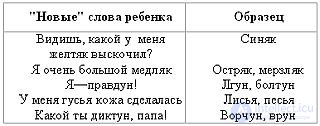

Word-making is one of the most important features of the child’s speech development. This phenomenon was studied both in our country (N. A. Rybnikov, A. N. Gvozdev, K. I. Chukovsky, T. N. Ushakova, and others) and abroad (K. and V. Sterna, Ch. Baldwin and others). The facts collected by many researchers - linguists and psychologists show that the first years of a child's life are a period of enhanced word creation. At the same time, it turns out that some “new” words are observed in the speech of almost all children (for example, “all”, “real-life”), while others are found in some children and not in others (“Mom, you are my washing dog!”, “ what a dictary you are, dad! ”, etc.).

KI Chukovsky emphasized the creative power of the child, his amazing sensitivity to the language, which are revealed most clearly in the process of word creation.

N. A. Rybnikov was amazed at the wealth of children's word formations and their linguistic perfection; He spoke of the word creation of children as "a hidden children's logic, unconsciously dominating the child's mind."

What is this amazing ability of guys to create new words? Why is it so difficult for adults to use word-making, and children are pleased, made laugh and surprised by a multitude of new words built according to all the laws of the language, which the child, in effect, is just beginning to master? Finally, how can we explain the word-making, along with the stereotype of the child-assimilated speech patterns, which we have already spoken about in some detail? Let's try to understand these issues.

First of all, let's see how word-making manifests itself in the speech of children.

Here it is interesting to cite some observations of the psychologist T. N. Ushakova, who has done a lot in studying the creativity of children.

TN Ushakova identifies three basic principles by which children form new words: a) a part of a word is used as a whole word (“word fragments”); b) the end of another (“alien” endings) is added to the root of one word, and c) one word is composed of two (“synthetic words”).

Here are examples taken from the work of T. N. Ushakova: "Word-fragments":

1. Sculpture (that which is molded): “We sculpted, sculpted, and sculpted” (3 years 6 months).

2. Groin (smell): “Grandma, what does it smell like, what is this smell here?” (3 years 6 months).

3. Jump (jump): "The dog jumped a big jump."

(3 years 10 months).

4. Dyb (noun from adverb “on end”): “Your hairs stand on end”. - “Is it up?” (4 years 11 months).

Adding to the root of the "alien" end:

1. Blizzards (snowflakes): “The blizzard is over, only blizzards are left” (3 years 6 months).

2. A tornness (hole): “I don’t see where the tornness on a blouse” (3 years 8 months).

3. Light (light): “A piece of light on the floor” (3 years 8 months).

4. Helping (help): “To dress yourself, without helping?” (3 years 8 months).

5. Truth (telling the truth): “I am the truth!” (4 years).

6. Smell (smell): “Why drive me to this smell?” (4 years 7 months).

7. Dryness (dryness): “Do you know that hippos can die from dryness?” (5 years).

8. Burota (noun from the adjective “brown”): “This is a brown bear - look what a bustard” (5 years 10 months).

9. Quest (searches): “I didn’t look for a button, I forgot about this quest” (4 years 10 months).

10. Imetel (the one who has): “I am the breeder of lard” (6 years).

11. Terrible (terrible): “Do not tell about your terrible things” (6 years).

"Synthetic words":

1. Liars - a thief and a liar (3 years 6 months).

2. Bananas - banana and pineapple (3 years 9 months).

3. Tastes - tasty chunks (4 years).

4. Babezyana. - monkey grandmother (4 years).

In our observations, many synthetic verbs and adjectives are noted: icebreaker ("icebreaker, it is icebreaker"), pochaypit ("we have already pochaypili"), "huge"

(huge and huge - “a house so big, just huge!”), mapin (“I am a mapina daughter”, that is, mother's and father's), all people (“this is not your teacher, she is all people!” - m. e. total).

How to get the "broken words" is not difficult to understand. A.N. Gvozdev drew attention to the fact that, starting to speak, the child first as if pulls out a stressed syllable from the word. Thus, instead of the word “milk” he says only “ko”, later “moko” and, finally, “milk”. Hence the fragments of words in the speech of young children. Take at least the word "sculptor" (that which is molded). We say: sculpt, molded, etc. - the child also highlights the stressed syllable "lep".

The second way a child creates new words - joining the root of the word “alien” ending - is also very common. These words sound especially peculiar: blinks, kindness, cleverness, smelly, rejoicing, etc. We, adults, do not say such words. And yet, if you look closely, it is from us that the children receive samples for creating such word-formations, therefore, here too the mechanism of imitation ultimately operates. After all, the child has created a “sandwich” on the basis of the word “snowflake”. But are there few words in the Russian language that are similar to "bitter" and "borax"? Suffice it to recall "deafness", "nausea", "crampedness" and many similar words. The child came up with the word “cleverness” (“Cats are the first by cleverness”) - but didn't he hear the words “stupidity”, “weakness”, “timidity”, etc.? 1.

In some cases, the baby, having heard some verbal form, now imitatively creates a new one. “What is the punishment that because of coughing you cannot go to the kindergarten,” says mom. “And for me, this is not a punishment, but a joy at all!” Answers the five-year donka. In such cases, the imitative origin of the new word is obvious to us. In most cases, the pattern by which a new word is created was acquired by the child sometime earlier, and therefore for the people around them the “new” word of the child is a revelation.

One can cite many examples of such a “distant” imitation of what the child has memorized before. Remember, we talked about a kind of “filing cabinet” in the Wernicke zone (the auditory speech area)? New words and built on patterns that are stored there.

It is also interesting to see how “synthetic words” are created. In such words as “liar”, “bananas”, “huge”, there is a clutch of those parts of the word that sound similar: a thief - a liar, a banana - pineapple, a huge one - huge, etc.

Otherwise, those words that sound different, but are constantly used together, for example, the words "tea" and "drink" (you get the verb "Chaypit"), "take out" and "take" (take out - take me a splinter), " all people "," all people "(all people)," in fact "(real-life). These words are built on the same principle as the “synthetic words” of adults: a collective farm, a state farm, a plane, a universal one, and many similar ones. In this form of word-making, the meaning of speech patterns also manifests itself, which the child constantly hears ...

Now you can answer the questions posed at the beginning of this section. Word-making, like learning ordinary words of a native language, is based on imitation of the speech stereotypes that surrounding people give to children. Not a single “new” child’s word can be considered absolutely original - in the child’s dictionary there is necessarily an example according to which this word was built. Thus, the assimilation of speech patterns and here is the basis. The use of prefixes, suffixes, endings in children’s new words is always strictly in accordance with the laws of the language and is always grammatically correct - only combinations are unexpected. In this respect, those who emphasize the subtle sense of language in children are absolutely right.

But this subtle sense of language distinguishes the entire course of the formation of children's speech, it does not manifest itself only in word creation. Moreover, if we consider children's word-making not as a separate phenomenon, but in connection with the general development of a child’s speech, the conclusion is that it is not based on the child’s special creative powers, but on the contrary, a pronounced stereotype of his brain’s work. The main mechanism here is the development of speech patterns (patterns of the most pronounced verb forms, the inclinations of nouns, changes of adjectives by degrees of comparison, etc.) and the widespread use of these patterns. A sample for the “creation” of a new word can be given now, or it can be learned earlier, but it always exists.

When children reach about the age of five, their language begins to fade. Less and less you hear “new” words. Why is this happening? Dry up the creative abilities of the child? But after all, we have already said that this is not about creativity, but about general principles for the development of speech. It was just that by the age of five the child had already firmly mastered the turns of speech that adults use, now he subtly distinguished various grammatical forms and began to freely navigate in which of them and when to apply. So disappear "my moyashechka", "bad boy" and other amazing words that give such a charm to the speech of a small child.

So, word creation at a certain stage in the development of children's speech is a natural phenomenon and expresses insufficient mastery of the variety of grammatical forms of the native language; it is based on the same principles of the brain as the direct assimilation of the verbal material that we consciously give to our children.

Probably, these conclusions sound more prosaic in comparison with the widespread point of view on children's word creativity, but they make it possible to come closer to understanding the essence of this most interesting phenomenon.

- Do you want me to tell you a fairy tale? - often offers toddler mother or grandmother (of course, they are the most interested listeners).

At the age of three to five or six years, children love to tell fairy tales composed by themselves. For the little ones, this happens in the form of “reading”: they hold an open book in their hands and “read” it. But more often the child is attached more comfortably about someone from the family and asks to listen to his fairy tale.

During the third or fourth year of life, a child has a further complication of speech patterns: the phrases become verbose, their grammatical structure is improved, but stereotype makes itself felt here, although it takes on a new form. Now you can often observe that the child takes whole ready-made phrases and makes up a story, a fairy tale. This is one of the most important manifestations of the development of a child’s thought-speech activity: the abilities of verbal thinking and its connected expression are trained in it.

Some parents have a negative attitude to the inclination of children to tell various stories and fairy tales, considering that this too develops a fantasy. But the child needs it. If he talks little, he should be called to such stories, asked to “read” or tell a fairy tale and listen to it carefully; Sometimes you should give some details or ask a few questions. (FOOTNOTE: Unfortunately, parents rarely write down fairy tales of their children, and therefore they are difficult to collect. And it is necessary to write down fairy tales without fail. Or during the child’s story, or, as a last resort, immediately after the story.)

The first tales of children about three years old are very simple and short - just a few phrases, and the phrases are almost completely taken from some well-learned fairy tale.

And yet, in these tales, kids try to say something of their own.

As a rule, a fairy tale begins with the words: "Once upon a time" or "once upon a time" ... This is, as it were, a symbol of what follows next is a fairy tale, and not a simple conversation. Fabulous expressions of speech are also used: “and now I asked,” “how can I not cry?”, “Whether it is long or short”, etc. The protagonist is usually an object, an animal or a person who is now caught up in the eyes of a child, and an event (beyond a single event, the matter rarely goes) is borrowed from a well-known fairy tale.

The phenomenon of speech stereotypy here makes itself felt very strongly: one can constantly observe that a word entails a memorized phrase with which it is firmly associated. Sometimes such a phrase, which has arisen from a random association, does not have a semantic connection with the previous ones, but the little storyteller does not notice this.

Here are a few fairy tales of children aged about three years.

Ira, at the age of two years, eight months, told the following fairy tale: “Once there was a Golden Flower. And to meet him a man. “What are you crying about?” - “How can I, poor thing, not cry? Ay-doo-doo, ih-doo-doo, lost man arc. "

At the dacha, where Ira lived, in the yard grew yellow flowers, which are called golden balls, hence the first character in the fairy tale. Someone had just visited the owner of the dacha, and she said: “The neighbor was a peasant”, - this is how the second character appeared, and the transition to the final words was prepared by the already existing strong association of the word “peasant” with the phrase “i-doo-doo, lost man arc. "

The roller in three years took the book and began to “read” in a monotonous voice: “Once upon a time there lived a mom, a dad and a roller. Still lived Murka. Murka sat on the window, and rolled out of the window, and rolled! Suddenly there is a bear. “Murka, Murka, I'll eat you! "Let me go, please, I will give you a dear ransom for me!"

Roller saw a cat sitting on the window-sill and began to tell a fairy tale about her; the word “window” drew a well-learned stereotype from “Kolobok”, and the word “let go” entailed another verbal stereotype from “The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish”.

Sveta of three years tells tales about Sveta the girl (obviously, referring to herself). Here are two of them:

- Once upon a time there was a girl Svetochka. Very nice girl. For a long time, whether for a short time, the girl Svetochka is walking, and towards her a cockerel. The cockerel, cockerel, golden scallop, butterfish, silk wool.

- Once upon a time there was a girl Svetochka. Here lived and was eating the testicle. Grandfather beat the egg, did not break. Baba beat the egg, did not break. Are you interested in?

As you can see, in the fairy tales of young children, it is possible to trace the associations that “pull out” precisely these phrases from the child’s memory.

Fairy tales told by older children have more complex plots and some development of the action. Although these tales retain the traditional beginning of "once upon a time" and are taken from "real" fairy tales, some specific idea is still clearly present here.

Some children's fairy tales are very moralistic and clearly have the goal of educating the adults around us: not only do we want to influence the formation of children's ideas or behavior through a fairy tale, but they often try to influence us in the same way.

Raechka is four years and three months old. Here is the fairy tale she told her mother: "In the third ninth kingdom there once lived a princess. She was so beautiful-beautiful: with a braid and with eyes! She had a mother. A very good and kind mother. She bought the princess ice cream, but did not force her to eat soup. Mom heard on the radio that children should be toughened up with ice cream, and so she toughened up the princess!" Do you understand the moral of this tale?..

Toma, at four years and five months, also composed a very instructive tale, which she told her parents, apparently for edification. “Once upon a time there lived a mom and dad. They had a daughter - golden hair, blue eyes, a red dress - all so colorful! But mom and dad still went to the movies, went visiting, and left their daughter at home. So mom and dad went to the movies. Suddenly a wolf came towards them. “I'll eat you!” Mom and dad got scared, screamed: “Don't eat us, don't eat us!” - and ran to their daughter!” One must think that after such a scary tale, Tom's mom and dad will think about how to go to the movies and leave their daughter.

Lera told her grandmother a similar tale at four years and five months: “Once upon a time there was a girl. In general, she was a very good girl: she washed her hands, ate well, and could sing songs. And the girl had a grandmother. So one day the grandmother went to the store, and suddenly a wolf came towards her. With such big teeth! And how he growled: "I'll eat you!" The grandmother ran home and never spanked her little girl or put her in the corner again!" Lida illustrated her own fairy tale (Fig. 36).

Fig. 36. They left the house and saw a cat.

It is interesting that both mom and dad and grandma, having met the wolves, immediately understood what was going on and immediately corrected themselves!

One of the moralizing fairy tales (by the way, children make up quite a lot of them) is the fairy tale by Lida (5 years 8 months): “Once upon a time there lived a girl, she ate poorly. Doctors from all over the world treated her, but she still ate poorly. And one doctor said to mom: “Go for a walk. You will suddenly meet a cat. Take her, and let the girl have a cat.” So they went for a walk. They left the house and saw a cat! They took her and brought her home. The girl and the cat began to drink milk together, eat cutlets, and everyone felt good! But some do not know and do not want to take a cat for their girls!”

A child’s fairy tale always reflects what worries him most at the moment. Garik, who was five years and six months old (this was in 1943), made up a fairy tale about how easy it was to end a war: “Once upon a time there lived a wizard. He really didn’t like the fact that there was a war – people were being killed, dads were going to the front. And so, after a long time or a short time, the wizard came up with a way to end the war: cut off the part of the land where the Germans lived! And that’s what he did: the whole earth spins in one direction, and Germany in the other!” And the boy added hopefully: “But can you really do that?”

The same boy told a very simple fairy tale about drainpipes – for some reason they made a big impression on him. “There was a house. And on one corner of the house there were two pipes: one long, and the other short. The long pipe was very beautiful – with three bends: one, two, three! Then suddenly it started raining heavily, first it poured onto the roof, and then into the pipes. “From the long pipe the water flowed onto the ground, and from the short one it splashed onto people – like this,” and the author shows this in the drawing (Fig. 37). This is a fairy tale without a moral, it simply tells about what interested its author.

Fig. 37. Drainpipes. Garik (5 years 7 months).

When Lenochka was about five years old, she often made up fairy tales about flowers, also of a narrative nature: “Once upon a time there lived such a beautiful, beautiful poppy: red, with a little purple in the middle! And there lived little bells, completely purple! One girl went for a walk. Suddenly, a poppy was standing in front of her. The girl said: “Poppy, I’ll pick you,” and she picked them. Then, suddenly, little bells were standing in front of her! The girl said to them: “Bells, little bells, I’ll pick you!” and she picked them. And the little flowers began to live happily ever after!”

Among the boys’ fairy tales, there are many that are full of technical details and almost devoid of action. But there are also adventure tales, sometimes with a warlike tinge.

Igorek was interested in electricity from an early age. At the age of five he composed many fairy tales of "electrical" content. "Once upon a time there lived a priest with a thick forehead. With him lived a priest's wife - that was his wife. Well, there was also a priest's wife and a worker named Balda. The priest with a thick forehead began to do the electrical wiring in the house. Well, of course, Balda did it. The priest didn't know how. They did the wiring and installed six-amp fuses. Do you know that fuses are six amperes, ten amperes and fifteen amperes? Well, they installed a six-amp fuse, but the priest with a thick forehead let the current flow to a hundred amperes! Can you imagine?! The current reached the fuse, the wire in it melted, and the current couldn't go any further! And if it weren't for the fuse, there would have been a fire! And Balda said to him reproachfully: "Priest, you shouldn't chase cheapness!" Igor not only told the story, but also drew an illustration for it (Fig. 38).

Fig. 38. Electrical wiring in the house near the oatmeal forehead. Igor (5 years old).

Not long before this, Igor had been read a book by B. Zhitkov, “Light Without Fire,” which described the structure of an electric bulb, fuse, etc. Under the impression of this book, a version of “The Tale of the Priest and His Workman Balda” arose.

Around the same time, Igor told a fairy tale about Baba Yaga: “There was a hut on chicken legs in the forest; Baba Yaga, a bone leg, lived in the hut. She needed electricity. And so they did, only the wiring was made for a weak current, only four volts! Such current is only good for a pocket flashlight, and not for a house at all! Baba Yaga will put dinner on the stove to cook, but it won’t cook! She will light the light bulb, but it won’t even glow!” Well, then Baba Yaga called the fitters, and the fitters redid the line, made it for as many volts as needed - 127! And everything was fine!"

Some more details about Baba Yaga's life can be found in the fairy tale of five-year-old Seryozha: "Once upon a time there lived a Baba Yaga in the forest. She had to go very far to work. And in the forest there are no buses or trolleybuses. And Baba Yaga began to fly in a mortar - it's like a helicopter. The motor in it is started by a battery: well, like in a Moskvich. Current goes from the battery to the motor, a spark jumps there, and the carburetor sprays gasoline, and the spray ignites, and the motor starts working. And the motor is connected to the propeller and whoosh-whoosh-whoosh! - and she flies! Baba Yaga only steers with the steering wheel!" (Fig. 39).

Fig. 39. Baba Yaga in a mortar. Seryozha (5 years old).

At the age of five and five months, Shurik loved watching TV and could not imagine his life without a TV. Naturally, the TV plays a very important role in his fairy tale: “Once upon a time, a hare and a fox lived in the forest. They built themselves huts. The hare made of

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 3. The kid spoke himself

Часть 2 INNER SPEECH OF A CHILD - 3. The kid spoke

Comments

To leave a comment

Pedagogy and didactics

Terms: Pedagogy and didactics