Lecture

The famous Russian proverb says: "The word belongs half to the one who speaks, and half to the one who listens." This means that for the person who speaks, and for the person to whom he refers, the spoken words must have some definite and, moreover, close content. “Can I come in?” - “Please,” people understood each other, since for both these words mean the same thing.

Sometimes this understanding is only apparent. Here is one of the many cases that I had to face during my trip to Poland. The Warsaw colleagues were so kind that they escorted me from the hotel to the university and back for a whole month, although I always assured them that I remembered the way. Only later it turned out that “remembering” in Polish means “forgetting” (it is close to the Russian word “forgetting”), and the words “remember the road” my friends understood as “forgot the way” and were probably surprised what kind of unaware guest !

Children to a certain degree are foreigners in our adult environment - they must learn not only the required forms of behavior, but also our language. Adults do not always appreciate the complexity of this task.

When we need to explain something to others, ask, etc., the easiest way to do this is with the help of words, isn’t it? Addressing children, we usually use this easiest and most convenient way for us. Mom and dad, grandmother and grandfather at home, a teacher and nanny in kindergarten — explain everything to children, ask them, give them orders using words. At the same time, it seems to everyone that the words introduced are understandable to the child as much as the one who speaks. Meanwhile, this is not always the case. Often a child puts into the word something completely different from the content that we put in it: sometimes it narrows its meaning, sometimes it expands.

Let's take a seemingly simple word: “dishes”. Mom asks 6-year-old Tanya to take all the tea utensils off the table to the kitchen. The girl took the cups with saucers and ran to play, and left the teapot, plates, sockets, spoons on the table. Mom was angry, and Tanya insists: "I took all the dishes, all of it!" There is no stubbornness or unwillingness to help her mother from the girl - she conscientiously carried out the assignment to the best of her understanding. The misunderstanding consisted in the fact that for Tanya the word “dishes” is only cups and saucers, and for mother this word means a much wider range of subjects.

Of course, not only the word "dishes", but also many others for Tanya have a much poorer content than for mom. We are not always aware of this and therefore are often angry with children in vain.

Sometimes young children literally understand an adult, not grasping that the words of their elders are just a figurative expression.

A tired grandmother puts three-year-old Marina to sleep and says: “When you lie down, I’ll have a holiday!” The girl spins for a long time, doesn’t fall asleep, and grandmother finally gets worried: “Why are you awake for so long, baby?” - “I want your a holiday to see! ”- the girl understood the words of her grandmother literally and overcome the dream in order not to miss an interesting event.

Four-year-old Seryozha rides chickens around the country. Mother came out of the house and scolded him: “So that I no longer see this! Do not afflict me! ”The boy promised eagerly, and the soothing mother went into the house; exactly two minutes later there was a desperate cackle of chickens and Serezha's cheerful cries. When the angry mother again ran out into the yard, the son asked with bewilderment: “Did you see it?” - the boy understood the words of the mother not as a prohibition to chase chickens, but as a warning so that she could not see it. Portable meaning that we often put in words is not yet available to children.

There are cases when an adult only implies a certain content of words: the situation is completely clear to him, and he believes that everything is clear to the child.

Here is the case in the middle group of kindergarten. Vadik eats jelly during a dinner with a snort. “Vadya, how are you eating?” The teacher asks irritably. “Eat well!” (The boy is eating and really with an appetite!) “Come on, go out the door for such good food!” The teacher drove Vadik from behind the table for snorting while eating. But was it clear to the child what happened? No, he understood the words of the teacher literally, and when he was later asked what he had been punished for, he replied: "For eating well."

One teacher said that four-year-old Andryusha, whose panama had slipped to the side, and sandals were not buttoned, she said sternly: “Andrei, tidy yourself up!” He nodded his head - now everything will be fixed. After a couple of minutes, the teacher went up to the boy again: on his face was the joy of a conscientiously executed case, but everything was still on him, only the right sandal was dressed on the left foot, and the left one was on the right foot! Try to guess what these adults want when they throw their orders on the go!

Sometimes children put their own, completely unexpected content into the word. Igorek, 4, and 6 months old, was eating porridge and coughed, and figures scattered around the table. Pointing at them, the boy shouted: “Look, Mom, I showered the entire table with ridicule!” Igor was read “Ugly Duckling” many times, and it says that all the birds showered the duckling with ridicule. Not knowing what it is, the child imagined the ridicule as something shallow, hard than can be sprinkled.

All cases like those described here show how difficult it is for children to grasp the essence of what adults say. Very often adults themselves are to blame for this - they forget that the level of understanding of words in children is much lower, and the figurative sense or irony is completely inaccessible to them.

How to make the child learn to put in the words the same content as adults? So we used the word “learned”, which means that we assume the development of the semantic content of the word based on the development of conditioned reflexes. Yes, this is the case, and it is very clearly seen if we trace how the understanding of words in children develops. Let's try to do it.

At the end of the first year of life, the child gives the right reactions to the many words addressed to him. “Show the nose!”, “Make a hand!”, “Where is the mother?” - we say, and the baby shows the nose, claps her hands, etc. “As he already understands a lot!” - we conclude. So the words are already becoming signals for the child?

But let's not rush to conclusions and look closely at the behavior of the eight-month Alyosha, who just "understands" many words already. The nanny holds him in her arms and asks: “Alexis, and where is the mother?” The kid, smiling, turns to his mother. When the same question was asked to Alyosha, who was lying in a crib, he did not make any attempt to look for his mother. But it was enough for the nanny to take him in his arms, as he again turned towards his mother when they asked him where she was. Alyosha was picked up by her mother’s friend. “Where is mom?” - and again there is no expected reaction!

So, what we first took for understanding the words is not really so. What is it? Special observations have shown that at first the child begins to understand not individual words, but whole phrases. Then it turned out that the phrase was initially not perceived on its own, but only as part of some more general effect on the nervous system. In the example with Alyosha, we have already seen that the correct reaction to the question “where is mom?” Is obtained only if this phrase is addressed to him in a familiar environment, if someone from close people speaks with interrogative intonation, etc. D. The phrase here is a part of some whole picture. If this or that detail — the situation, the person, the voice, the intonation changes, the picture becomes unrecognizable to the child, and he can no longer give the reaction that is expected of him.

At the first stage, in order for the child to respond to the phrase, it is necessary to have a number of direct stimuli 1 . But gradually the number of stimuli needed to cause a reaction decreases. This is clearly seen from the table.

We see that at 7–8 months the child will give the expected response to the phrase (for example, show the nose) only if he is sitting, if he is in a familiar environment, if a person with whom he speaks and with a certain intonation speaks with him. The phrase itself, in fact, does not matter (it is marked with a minus). This means that the child responds with the correct motor reaction not to the phrase, but to the whole situation as a whole 1 .

Note: Plus means that this component of the stimulus is necessary for obtaining a reaction, and a minus means that its presence is optional. The plus or minus sign means that the role of this component begins to grow.

Only gradually does the word become a stronger component of a complex stimulus, while its other parts lose their meaning. First, the position of the body becomes indifferent, then the setting; after a while, the phrase may already pronounce a new face; the longest is the value of the usual intonation. Finally, words become independent conventional signals — the child responds to them with the right responses, independently of other “picture details” 2 .

Under natural conditions, the composition of a complex stimulus (in our example, the position of the child’s body + the visible part of the room + the speaking person + his voice and intonation + the very words) does not remain strictly constant each time. That child is kept face one way, then the other; the mother, the nanny, etc. are addressed to the baby, etc. The most frequent member of a complex stimulus is the phrase; the conditioned connection is fixed on her in the child's brain.

Many researchers who have studied the development of children's understanding of speech (for example, A. M. Leushin) find that, first, a phrase, not a word, will be the “unit of speech” for them.

For example, in the phrase “show the nose” you need to know the meaning and the words “show”, and the words “nose”. But the fact is that the baby of the end of the first - the beginning of the second year does not distinguish either one or another word in the phrase, but perceives it together; this phrase is for the time being just a sound signal to a certain movement: “show the nose” - reach out to the nose, “give the handle” - give a hand, etc.

Only much later, when individual words acquire a signal meaning, the phrase will become a more complex stimulus than a word. The isolation of words from a phrase is a further stage in the development of the understanding of the speech of other people.

At the beginning of the second year of life, the child learns the names of many objects, that is, the words become for him conventional signs, signals of the corresponding objects. This is kitty, this is a spoon. The child learns the names of actions: give, take, show, etc.

As words are associated with objects and actions, they are separated from the phrase. However, in order to give out the words “give” and “pen” from the phrase “give a pen”, for example, a child and other adults have to work hard.

Adults, for example, should pronounce each of these words in different combinations with other words and accompany the conversation with actions with the so-called object. The mother washes the child's hands and says, “Let's wash our hands clean and clean!” - while doing so she lathers them and pours water on them. “Where is Mitya's pen?” Here it is, pen! Caught a pen! ”- and mother tickles and kisses his little hand. The word “pen” and those or other actions with the hands of a child are repeated many times, and the necessary connections are established between them. The word “give” is also used in conjunction with various words: “give a doll”, “give a pen” and is thus associated with various objects.

So gradually the words are pulled out of the phrase and begin an independent life for the child - each of them individually acquires its own meaning.

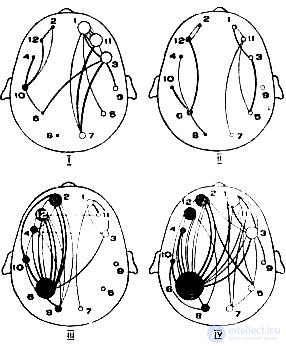

Very interesting facts were obtained in our laboratory by T. P. Khrizman, V. N. Zaklyakova, and L. M. Zaitseva when studying the relationships that arise between different parts of the brain during the action of words unfamiliar to a child and words that have acquired the meaning of names. In children, the brain's biocurrents were recorded and then mathematical (statistical) processing of records was carried out, establishing which areas of the cortex were most closely related to each other.

In fig. 12 shows the diagrams of the obtained connections between the symmetrical points of the cortex in the most critical zones: the frontal, motor, temporal, inferior and occipital zones. The calculations showed the nature of the connections obtained: some of them were weak, others were strong or very strong. The diagram shows the average data for a group of children aged from one year to one year and three months.

Fig. 12, I shows the relationship between the items studied, which were obtained at rest. You can see that between the frontal, motor, temporal, and occipital regions, a small amount of weak connections were found, and there are essentially no connections between the frontal and lower nephritis.

Fig. 12. Diagrams of the interaction of different parts of the brain in children beginning of the second year of life:

I - at rest, II - under the action of an unfamiliar word, III - under the action of the word that has become the name of the object, IV - when the name of the child is called.

Thin lines - weak bonds, medium - strong bonds and thicker - very strong bonds.

The numbers show the points at which biocurrents were recorded: 1, 2 - in the frontal areas, 3, 4 - in the motor areas, 5, 6 - in the inferior, 7, 8 in the occipital, 9, 10 - in the temporal (sensory speech) areas, 11, 12 - in the frontal (motor speech) areas.

Now the word "matryoshka" or "mushroom" is pronounced unfamiliar to the child. In fig. 12, II it can be seen that little has changed in the electrical activity of the brain compared with the state of rest.

Next, the child is shown a nested doll (or mushroom), is allowed to play with this object and is called. This is repeated several times until the child learns the signal meaning of the word. Now that the word has become a name, it is checked what effect it has on the brain (Fig. 12, III). The pattern of connections between different zones has changed dramatically: strong and very strong correlations have appeared, which are especially pronounced between the frontal and lower tempered areas. Almost the same picture of interrelations was obtained when naming the child’s name, which he knows well (Fig. 12, IV).

These data indicate the important role of the frontal and inferior areas of the brain in the development of the signal value of the word. These areas are called associative, because they carry out the connection of individual reflex acts in the system.

From the data presented here it is clear that in order to get the connection of the word with the complex of sensations from the subject, the participation of the associative brain regions is also necessary.

So, the first step in the development of speech understanding is the formation of the naming function of the word: everything that is around the child, and everything that he does, gets a name.

For mastering the name, actions with objects are of great importance. In very interesting experiments, G. M. Lyamina showed that even at 1 year 8 months - 1 year 10 months, children hardly associate a word with an object if they only see it.

Children were shown individually five items and called each of them. Then all five subjects were laid out in front of the child and were given a task: "Show this or that" or "give this or that." It turned out that children were often mistaken in the choice of subject. If today this or that object was called to the child several times and finally sought the right answers, then the next day he again made many mistakes.

The training is completely different in cases when children are given to play the so-called object, - in such conditions, the kids learn the names very quickly and remember them well. The child turns in the hands of a rubber hare, tries to nibble at it, and the adult at this time repeats the word: “Bunny, bunny!”

Not only the names of objects, but also ideas about them are formed easier if the child has the ability to manipulate with these objects. This should be borne in mind by parents and employees of children's institutions. Here's a nurse in a nursery group shows the rabbit to the kids and explains: “This is a rabbit, it's his ears — look, how long! But the tail is very short! ”, Etc. Children smile, try to touch the rabbit, but the teacher removes them - and then her hands need to be washed, and the rabbit will frighten. The audit shows that after such an activity the children know almost nothing about the rabbit (not everyone can even say later that it is a rabbit, they say: “Kisya!”).

If you give hold to the rabbit, allow it to be stroked, touch the ears and tail, then it seems as though they include some special memory mechanism! - the kids will remember and call later the rabbit itself, and its ears, and its muzzle, and its tail!

Of course, you immediately have a question: what is the matter? Why actions with objects so help the assimilation of the names of objects and the development of ideas about them? In order not to disturb the order of the story, we will find out this surprising circumstance later, but for now just remember it.

“The word is just as real a stimulus as any other, but at the same time it is as comprehensive a stimulus as no other”, wrote IP Pavlov (FOOTNOTE: I. P. Pavlov. Complete. Collected papers. M . —L., Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1949, Vol. 3, p. 337.). By the term “comprehensive stimulus” he wanted to emphasize the property of the word to summarize many, many objects and phenomena.

Of course, the word does not immediately acquire this property. At first, as we saw in the previous section, the word means only one item: “spoon” is the name of only the spoon that the child eats, “chair” - only his chair, etc. It will take a lot of time until the concepts are developed (a spoon in general, a chair in general).

На первый взгляд кажется, что превращение слова-названия в слово-понятие происходит у ребенка само по себе: он видит разные стулья, часто слышит при этом слово «стул», и так постепенно слово приобретает для него все более широкий смысл. Однако когда попытались проверить это, то дело оказалось несколько сложнее. Давайте познакомимся со специальными опытами — ведь в опытах условия всегда проще, чем в жизни, и поэтому легче выяснить сущность тех явлений, которые изучаются.

Прежде всего нужно было установить, при каких условиях слово скорее превращается в обобщающий сигнал. Может быть, этот процесс облегчается, если ребенку часто называть предметы? А может быть, опять нужны действия с этими предметами?

In order to answer these questions, two groups of children aged 1 year - 1 year 3 months were taken in the orphanage. In the first group, for two months each child every day, 10 times for five seconds, was shown an unfamiliar object - a book and said: “Book! A book! ”The children each time turned their eyes and turned their heads in the direction of the displayed object. During the observations, this reaction was repeated 500 times. In fig. 13 shows one of these experiences.

Fig. 13 . Experience with a child of the 1st group.

С детьми второй группы в опытах применяли также одну книгу, но с ней производили большое количество действий. «Вот книга!», «Возьми книгу!», «Открой книгу!» и т. д. — всего 20 различных команд, в каждую входило слово «книга», и каждая требовала определенной двигательной реакции. Эти двигательные реакции повторялись лишь по 50 раз за время наблюдений. Примеры таких опытов вы видите на рис. 14 (а, б, в, г).

Fig. 14а. Опыт с ребенком 2-й группы

Fig. 14б

Fig. 14в

Fig. 14 г

Then, in both groups, control tests were carried out, consisting in the fact that many different items were laid out before the child: cubes, dolls, toy dishes and several books differing in size, thickness, color of the cover, etc. The adult addressed the child with the words : “Give me the book!” At the same time, it was observed whether the child chose only the book with which the word “book” was associated in experiments, or he took other books that he had seen for the first time; Whether he limited himself to choosing books or collecting all the things laid out in front of him in a row.

Результаты оказались следующие. Ребята из первой группы брали одну книгу — ту, с которой имели дело в опытах, и отдавали ее экспериментатору. Когда их просили взять еще книгу, то они или брали первый попавшийся предмет (это могла быть кукла, кубик), или же не давали никакой двигательной реакции (рис. 15). Значит, для детей этой группы слово «книга» не стало сигналом, обобщающим многие книги, оно осталось названием одного конкретного предмета. Отсюда можно сделать вывод, что большое число повторений слова с показыванием предмета не способствует развитию обобщающего действия слова.

Fig. 15. Контрольный опыт с ребенком 1-й группы.

Все малыши второй группы в этих испытаниях выбирали из лежащих перед ними вещей сначала знакомую по опытам книгу, а потом и все другие. Они не только смогли отличить книги от других предметов, но и обобщить их словом «книга» (рис. 16). Здесь уже можно говорить о том, что слово приобрело для детей значение понятия и стало относиться ко многим предметам, в чем-то сходным, а в чем-то отличающимся один от другого. Это дает основание думать, что для превращения слова в понятие особое значение имеет выработка на него большого числа условных связей.

Fig. 16. Контрольный опыт с ребенком 2-й группы.

Далее встает еще один, очень важный вопрос: играет ли роль только число выработанных условных связей или и характер их? В опытах, о которых только что рассказано, вырабатывались двигательные условные реакции. Было решено сравнить их роль хотя бы с ролью зрительных условных рефлексов. Для этого провели дополнительные эксперименты на детях 1 года — 1 года 3 месяцев. В одной группе на то же слово «книга» выработали 20 условных двигательных рефлексов («возьми книгу», «положи книгу» и т. д.), а во второй — 20 зрительных условных рефлексов: говоря одну и ту же фразу «вот книга», ребенку показывали по очереди 20 различных по формату и цвету книг. Таким образом, в первой группе зрительные раздражения были однообразны, действий же производилось много, а во второй группе, наоборот, зрительные воздействия были разнообразны, а действие одно и то же.

Когда провели контрольные испытания, то оказалось, что для ребят первой группы слово «книга» стало обобщающим сигналом, а для детей второй группы — нет.

Из этих опытов мы имеем право заключить, что для того, чтобы слово-название стало словом-понятием, на него надо выработать большое число именно двигательных условных связей.

Как видите, ребенку будет полезно, если вы станете учить его производить с каждым предметом как можно больше действий: возьми, подними, положи, открой, закрой и т. д. и т. д.

Нередко в семье бывает так: с маленьким ребенком много разговаривают, поют ему песенки, а когда он подрастает — без конца читают ему. Как будто создаются благоприятные условия для развития речи. Между тем результаты часто оказываются далеко не блестящими. Вот один из таких случаев. Оля Р. (2 года 4 месяца) — единственный и долгожданный ребенок в семье; днем она на попечении бабушки, которая то рассказывает сказки, то поет песенки, всячески развлекая девочку, а вечером мама и папа вырезают из бумаги кукол и устраивают перед ней инсценировки сказок. Оля сидит, вяло слушает и смотрит на все совершенно пассивно. Проверка показала, что девочка знает лишь названия отдельных предметов (около 150 слов вместо 400) и около 20 названий действий. Отсюда очевидно, что большая часть того, что родители и бабушка рассказывают Оле, для нее остается просто шумом — она не усваивает и не понимает слышимых слов.

Другую девочку этого же возраста — Зою С. занимают играми, в которых она сама принимает деятельное участие: одевает и раздевает кукол, кормит, купает их и т. д. или же складывает из кубиков домики. Предметы, которые Зоя берет в руки, ей часто называют, как и действия, производимые с этими предметами. «Вот косынка, надень Кате косынку. Так, а я помогу тебе завязать ее — вот так! Теперь Катя пошла гулять: топ-топ, топ-топ, Катя!» Зоя передвигает куклу, а мать время от времени вступает в игру и говорит о том, что сейчас делает кукла.

Сравнительно небольшое время общения Зои со взрослыми наполнено активной деятельностью девочки и сопровождается разговорами, имеющими для нее смысл. Количество слов, которые Зоя понимает, достигает 450, многие из них имеют уже обобщающего значение. Нам вполне понятно почему, не правда ли? Вспомним опыты с книгами: 20 зрительных и 20 двигательных условных связей!

У Зои вырабатывается на слова большое количество именно двигательных условных рефлексов, поэтому у нее легко идет процесс усвоения слов-названий и процесс превращения их в слова-понятия. Оля же оказалась в положении тех детей, которым показывали много книг, называли их, но не давали с ними ничего делать, поэтому слова у нее медленно приобретают значение сигналов и совсем не развивается их обобщающее значение.

Sometimes you have to face a different situation: the parents believe that the child should be taught to be independent as soon as possible and to deal with it less. They believe that playing and talking with a baby is self-indulgence. Parents

Vali P. (1 year and 6 months old) hold just such a point of view. The girl is seated and a small playpen or in a bed, toys are placed near her and they give her the opportunity to have fun as she is able to. Valya takes a doll, a parrot, knocks them on the barrier, nibbles them and throws away the toy; most of the time, the girl sits looking ahead, motorly, she is little active. Of course, it is very convenient for others, but the child’s speech in such conditions will not develop.

The independence of the baby is not in the fact that he will sit quietly, left to himself, but in that he learns the necessary actions with objects. The same actions are necessary for the development of the child's speech.

It is interesting to talk here about the experiments conducted by the teacher G. L. Rosengart-Pupko: she studied the development of the generalization of subjects with the help of the word in young children. One task was that the children of 1 year and 6 months - 2 years and 6 months were given a toy yellow teapot and asked them to find a second teapot among the toys laid out on the table (it was different in color). The second task was somewhat more difficult for children of this age: the same teapot and a set of pictures with images of various objects, including a teapot, were given, and it was necessary to find it. It turned out that if the child knew the name of the object, he would select the second desired object or its image even in the case when the object was different in size and color. If the child did not know the name of the object that was given to him as a sample, then usually he would pick up a pair of colors or some other random trait. These games, which were conducted as special tests, can be successfully used by parents to develop the generalizing function of the word.

During the formation of speech, the child begins to consistently allocate the semantic meaning of the word, and the clearly perceived signs of objects more and more recede into the background. With a delay in the formation of speech, this process is naturally delayed, and the child remains at a low level of mental development for a long time.

The same patterns are also observed in older children, the Leningrad psychologists L. A. Lyublinskaya and F. S. Rosenfeld note that five-year-old children very successfully make groups of objects from pictures — fruits, furniture, clothes, etc. Sometimes they make mistakes, for example, they unite a fish, a watering can, a boat into one group, explaining that “they all need water”; they put together a rake, a pencil and a ruler, since “they are all long”. But as soon as the children learn the generalizing words “transport”, “garden and office supplies”, the described errors are immediately eliminated.

So, the word helps to make a generalization of objects based on the selection of their essential properties, and not random. Please note, however, that all the experiments described here required the active actions of the child - whether it was a matter of selecting similar objects (or pictures with their images) or making groups of objects.

Here we are again confronted with the fact that actions with objects contribute to the formation of the generalizing function of the word, and again we are forced to postpone the explanation of this circumstance.

Such a question was once asked by seven-year-old Marisha K. She noticed that only the chairs fit into the word “chair”, and the furniture also contains tables, sofas, and much more. Have you noticed that some words really mean a narrower circle of objects or phenomena than others?

Compare the words "tree", "oak", "birch" and "trees", "plants" or "doll", "ball" and "toy", "thing" - and you will immediately see that words like "tree "," Oak "," doll "," ball "cover some rather limited group of objects, and the words" trees "," toy "have a broader meaning.

Words by their generalizing meaning can be divided as follows:

I degree of generalization - the word means one particular subject (for example, "doll" - only this doll). The word several times coincided with the sensations of this thing, and a strong connection was formed between them. This degree of generalization is already available to children of the end of the first - the beginning of the second year of life.

II degree of generalization - the word already designates a group of homogeneous objects (“doll” refers to any doll, regardless of its size, the material from which it is made, etc.). The meaning of the word is broader here, and yet it is less specific. Grade II generalization can be obtained from a child by the end of the second year of life.

III degree of generalization - the word means several groups of objects with a general purpose (“toys”, “dishes”, etc.). So, the word "toys" summarizes the dolls, and balls, and cubes, and other objects that are intended for the game. The signal value of such a word is very wide, however, it is significantly removed from the specific images of objects. This degree of generalization is achieved in children of three to three and a half years.

IV degree of generalization - the word as a result of a number of previous levels of generalization (the word “thing”, for example, contains generalizations given by the words “toys”, “dishes”, “furniture”, etc.). The signal meaning of such a word is extremely broad, and its connection with specific objects can be traced with great difficulty. This level of generalization is available to children only in the fifth year of life.

It is clearly seen here that the higher the degree of generalization by a word (i.e., the more objects it contains in itself, as Marisha put it figuratively), the further it takes us away from immediate sensations.

This process of replacing sensory images with less and less sensual is very vividly described by I. M. Sechenov. Here, he says, a small child sees the Christmas tree, touches it, pricks it with needles, feels a resinous smell - and the whole complex of sensations is associated with the word "Christmas tree". At first, this word replaces one particular set of sensations and is firmly associated with it. Gradually, the child gets acquainted with other trees: small and large, with trees in the forest, with a Christmas tree decorated - and all these objects, somewhat similar, and in something different, are called with one word "Christmas tree". The word begins to acquire an ever wider meaning, and at the same time it is moving further and further away from the immediate sensations that any particular tree causes. This is the "Christmas tree in general."

But now the child recognizes the word "tree", which has an even broader generalization: it includes trees, and oaks, birches, etc., etc. The word "tree" is further away from immediate sensations (from "sensual roots ", As Sechenov called them). The word "plant" is a generalization of an even higher order and very far from specific images of trees, flowers or berries.

The degree of connection of the word with "sensual roots" is especially evident in the drawings of children. Children 5–6 years old give very expressive images of a Christmas tree or a birch tree, which makes it possible to immediately recognize them as a Christmas tree or birch (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17. Birch painted by Olya K. (6 years old).

A child represents a tree in the form of a diagram: the trunk and contour of the crown already without any details (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. The tree depicted by the same girl.

Even the older child cannot paint the plant, although he already knows very well that trees, bushes, flowers, and vegetables are all plants; the connection with the “sensual roots” here is already very distant and does not cause any particular image in the child’s mind. When asked to draw a plant, the child usually answers the question: “And which one?” (Fig. 19).

Fig. 19. When asked to draw a plant, the girl responds with a question: “And which one?”

"This phase of psychic evolution in the field of thinking begins as if a major change ... the child thought, thought sensual concrete, and suddenly his objects of thought are not copies of reality, but some echoes of it, at first very close to the real order of things, but few - by the moment, moving away from their sources, "said I. M. Sechenov (FUNCTION: I. M. Sechenov. Favor. Works. M. — L., Academy of Sciences of the USSR, 1952, Vol. 1, pp. 365–366.) . The physiological basis for the development of a new form of reflection of reality - through verbal signals - is the analysis and synthesis of not single stimuli, but their complexes, generalizations, presented in words ...

What determines the fate of the word - will it have an I or IV degree of generalization, that is, will it replace a complex of sensations from a single object, or will there be several categories of objects? Perhaps this is determined by the degree of maturity of the child’s brain — after all, we see that higher degrees of generalization can be obtained only from older children?

The answer to the last question may be negative. Although the maturation of the brain has a certain value, it is impossible to explain the development of II, III, IV and higher levels of generalization with the word.

As it turns out I and II degree of generalization, when the word becomes the name of a single object or group of objects, we have already considered. The word must connect with the sensations from the object and, most importantly, with the actions that the child performs with it.

Grade III generalization is developed somewhat differently. Here the same subject receives not one name, but two. Psychologist N. A. Menchinskaya studied in detail this process. For example, a toy bear is called both “bear” and “toy”, at the same time the word “toy” means not only a bear, but also a ball, a doll, a car, etc. What is so common between such different objects, why they are called in one word? And what they have in common is that they play - they have the same playable reinforcement, as physiologists say. In exactly the same way, a spoon, a plate, a cup, etc., we also call “dishes”, because all these objects receive the same reinforcement — food. This means that the word is associated with a whole group of objects due to the fact that they all relate to one type of activity - play, food, etc.

Observations of our laboratory showed that the development of a third degree of generalization by a word requires considerable time and effort. For example, here are the results obtained from three-year-old children in developing the third degree of generalization by the word "toys." Pre-selected 20 words - the names of toys, which already had a II degree of generalization, that is, they were a doll in general, a ball in general, etc. In the experiments during the game, objects were called (doll, cube), the word “ a toy". The child was asked: "What kind of toy do you want to take - a doll or a bear?" - or he was offered: "Give me one toy, well, that's a little car, and the rest of the toys - a top and ball - take yourself."

It turned out that the first four words with the II degree of generalization were associated with the word “toy” after 18 (on average) combinations, the next five words - after 10 combinations, and then it was enough to give 3–4 combinations. As the system of conditional connections to the word “toy” became more powerful, the inclusion of new connections in it was becoming more and more easy. (FOOTNOTE: This fact corresponds to a well-known pattern: the more conditioned reflexes are worked out, the easier it is to further develop them.)

That is why the formation of high degrees of generalization in a child with a systematic work with him is very easy. If there is no such work and the number of conditional link systems is small, then each concept is worked out with difficulty.

It should be emphasized that the development of the first two degrees of generalization is usually given sufficient attention to the word - in each family they diligently teach the baby to name objects and actions. As for the higher degrees of generalization, they are engaged in much less.

In the speech of children of three to five years, one can often hear words that have III and IV degrees of generalization: people, things, play, kind, evil, good, bad, etc. But do these words have such content for children that they really are can be evaluated as signals carrying high degrees of generalization? Most superficial checking often reveals that it is not.

In the middle group of one kindergarten, the children were asked the question: “What is food?” Such a common word should be known to all children of this age. And in fact, all the guys raised their hands and began to list confidently: carrots, cabbages, seeds, midges, worms. The children were asked leading questions, but they added nothing to this somewhat strange list. It turned out that in the classes in the group they often tell what kind of food hares and birds eat, but never talked about the food of people. Therefore, the concept of food was very narrowed - this is what birds and beasts eat, and what children themselves eat is “food” or “food”.

The difference between vegetables and fruits was explained by the guys as follows: “Fruits eat raw, and when boiled it is vegetables.”

Children could not give a clear separation of the concepts of wild and domestic animals. They, for example, attributed the squirrel, hamster, and tortoise to pets, as they live both at home and in a living corner in a kindergarten. Bears and tigers are also domestic animals: they perform in a circus.

Especially difficult for children are those concepts that are abstract. Children put their content into them, sometimes making them more completely unexpected for us.

Four-year-old Seva explains why you need to wash your hands with soap: it stings the eyes of microbes and they run away.

Three-year-old Vova refuses to play with his peer Zhenya, because that “nasty thief, every now and then does pants!”

One five-year-old boy tells his friend what an eloquent father he is: “He, you know, how wide his mouth is when he screams!”

Of course, these childish concepts are very funny. But we need to ensure that these concepts are correct and sufficiently complete. For this you need to use any time to talk with the child. It is necessary to show that it is from the objects surrounding the baby that they belong to the furniture, what to the dishes or clothing, etc .; offer the child himself to show what items are furniture, what are clothes.

For the development of higher degrees of generalization, it is important during the game, feeding, dressing to call objects as a more specific word, and more general. For example, to say: “This doll is probably a very good toy” or: “How many toys do you have - a doll, a little car, and a ball! What is your favorite toy? ”

We must not forget that abstract concepts are built on the basis of concrete representations. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to the children of the properties of the objects in question. For example, children know very badly what this or that object is made of. It is not enough to tell the child that this dress is woolen, and this is a print: you must show and allow to touch that and the other fabric.

In the middle group of the kindergarten, the difference between the big teddy and the small plastic bears was seen by the children only in size. To the question of what fabric the dress was made from, they answered: “From grandma's skirt”, “Mom bought”, “From the reds with flowers”. Of the many questions, only one - what the collar of the coat is made of - the children gave more or less correct answers: "Out of cat's fur", "Out of hair", "Out of rabbit", etc.

Quite a difficult task - the formation of common concepts about actions. The signal meaning of such words as “give”, “take”, “eat”, “show” is absorbed by children in everyday life quite early. These words are not difficult, as they contain the command to perform one simple action. In addition, the action itself will be stereotypical, very similar in relation to any subject. In order to take a spoon or a pencil, a doll or a handkerchief, an arm is stretched equally and an exciting movement is made with the fingers (of course, there are some differences in how widely the fingers are moved apart and which of them take a more active part, but these differences are not very significant). It is precisely because of the stereotype of the motor reaction to these verbal signals that they very soon receive a generalizing meaning. The child easily transfers the motor reaction developed by the words: “Show the nose”, “show the eyes”, “show the mouth” to new objects; without any special elaboration, it will show further kisu, watches, etc. The word “show” gets already a generalized character, becomes a concept.

However, we often address two-three-year-old children with orders and requests that also seem very simple to us, but in reality are extremely difficult for kids. “Go, wash your hands”, “Lay down neatly toys” and we often give many similar teams to the guys, not really thinking about the fact that each of them contains an entire program of actions. Look at what looks like in Figures 20, a, b, c, d, and the procedure of washing hands in action: you need to roll up your sleeves, open the faucet, take soap, soap your hands, put soap, wash off foam, shake off excess water and wipe your hands with a towel . Here it is necessary to perform not one movement, but a whole chain of them and, moreover, in a certain sequence, which must be memorized. If the child has not been taught to wash his hands properly, then the “go, wash your hands” command cannot contain this complex program of actions. In fig. 21 shows how the boy washes his hands for two years and ten months: he helped with water, shook him - and it was done! Probably, in this case, the content of the words “wash your hands” with him and yours does not match. This is obtained because such a simple command, it seems, does not contain the necessary content in the child.

The name of actions, as you can see, can also be a “comprehensive” signal, but if it implies a chain of actions, then it should be learned by repeated repetitions. Research by psychologists in the laboratory of A.V. Zaporozhets has established that only a child of about seven years can execute a complex team without prior training.

Why it happens? Работы физиологов показали, что удержание программы движений связано с участием лобных отделов мозга; на детях, в частности, такие данные получены в нашей лаборатории. Созревание же этих отделов мозга у ребят происходит медленно. Именно к семи годам степень зрелости лобных областей начинает приближаться к той, которая обнаруживается у взрослых людей.

Если у ребенка достигнуты успехи в развитии высоких степеней обобщения словом, то успокаиваться на этом нельзя, так как очень легко развивается обратный процесс — утрата словом обобщающего действия.

Подобное явление наблюдается нередко. Юра Т. до двух лет шести месяцев находился на попечении мамы и бабушки и уже довольно хорошо говорил, пользовался правильно рядом слов II степени обобщения. Но вот бабушка уехала, мать стала поздно приходить с работы, и ребенок почти полностью оказался на руках няни. Через полтора — два месяца речь Юры стала очень примитивной — словарь его обеднел, уровень обобщения предметов и явлений с помощью слов у него снизился. Например, раньше мальчик употреблял слово «игра» в широком его значении: оно обозначало игры в мяч, лото, картинное домино, с игрушечными солдатиками и многие другие; словом «сад» он называл Таврический сад, около которого он живет, скверы по прилегающим улицам и любой сад, который видел при поездках по городу. Теперь «игрой» стало лишь катание автомобильчика — других игр няня не позволяла, и Юра их начал забывать, а «садом» стал называться только садик во дворе, дальше которого няня не ходит. Многие другие слова у Юры таким же образом потеряли свое обобщающее значение.

Подобные факты мы наблюдали и в опытах, при выработке обобщающего действия слова «книга». Когда работа закончилась, то книги остались на полке на виду у детей, но больше их не трогали. Через месяц стали проверять, сохранилось ли обобщающее значение слова «книги». Для этого провели контрольные опыты, в которых ребенку предлагалось взять книгу из разложенных перед ним различных предметов. Что же получилось?

Из двенадцати детей семь взяли ту книгу, с которой имели постоянно дело в проводившихся ранее опытах, — для них слово «книга» опять стало просто названием одного предмета! А пять остальных детей выбрали книгу и еще два-три других предмета — у них уже и связь этого слова с определенным предметом стала слабой.

В чем здесь дело? Мы уже знаем, что развитие обобщающего действия слова зависит от выработки на него систем условных связей, причем особое значение имеют двигательные условные связи. Если эти условные связи не функционируют, то они постепенно угасают, как бы перестают существовать, а значит, теряется та основа, которая делала слово «многообъемлющим» сигналом.

Когда слова, имеющие II или III степень обобщения, начинают употреблять только по отношению к одному предмету, то они из слов-понятий опять превращаются в слово-название. Именно это получилось у Юры, это же мы видели и в наших наблюдениях, описанных выше.

Итак, для того чтобы приблизить понимание речи у детей к нашему, нужна систематическая работа с ними. Уровень обобщения, получаемого с помощью слова, не есть что-то постоянное, раз навсегда данное: в зависимости от количества систем условных связей, выработанных на слово, уровень обобщения этим словом может быть больше или меньше; при у гашении этих связей обобщающее действие слова утрачивается.

Уже дважды на протяжении этой главы возникал вопрос о том, почему действия с предметами способствуют развитию речи, и ответ на него мы откладывали. По-видимому, пора попытаться сделать это.

Из того, что мы говорили, очевидно, что в основе процесса понимания лежит выработка систем условных связей, благодаря чему слово как бы объединяется с комплексом ощущений от предмета. Иными словами, чтобы ребенок понял, что вот этот предмет называется «стул», нужно, чтобы зрительные, осязательные и другие ощущения от него связались между собой в единый образ предмета и далее со словом. И. М. Сеченов приводил очень хороший пример с колокольчиком: маленький ребенок видит этот предмет — получает зрительное ощущение, трогает его — возникает осязательное ощущение, колокольчик издает звук — добавляется слуховое ощущение, и, наконец, взрослый говорит: «динь-динь». Посмотрите, что происходит, говорит Сеченов: из последовательного ряда рефлексов получается представление о предмете, знание в элементарной форме. Он рассматривал этот процесс как следствие слияния нескольких рефлексов.

Но какова же здесь роль движения? Сеченов предположил, что ко всем ощущениям примешивается мышечное чувство: можно смотреть, не слушая, и слушать, не глядя; можно нюхать, не глядя и не слушая, но ничего нельзя делать без движения! Действительно, глаза обращаются в сторону зрительного раздражителя, обегают контур предмета, следят за его перемещением — а это все движения. Звуки тоже вызывают движение в сторону источника звука, происходит настройка мышц гортани на тональность действующих звуковых раздражений и т. д.

Изучая биоэлектрическую активность мозга, ученые установили, что любое воздействие — зрительное, звуковое, осязательное — обязательно вызывает повышение возбудимости двигательной области головного мозга. На детях этот вопрос изучался в нашей лаборатории — мы сопоставили роль зрительных, слуховых и двигательных ощущений в процессе формирования образа предмета. ВЫЯСНИЛОСЬ, что всякое ощущение по своей природе смешанное (как это предполагал И. М. Сеченов) — к нему обязательно примешивается мышечное ощущение, которое является более сильным по сравнению с другими. Поэтому, когда ребенок видит предмет, слышит его, трогает, в его мозгу возникает целая мозаика возбужденных очагов, и главенствующими будут те, которые вспыхивают в проекциях мышц глаз, шеи, рук и т. д. Очаги возбуждения в собственно зрительных, слуховых зонах, зонах кожной чувствительности будут слабее. При объединении ряда ощущений от предмета в единый образ слияние (синтез) происходит прежде всего в двигательной области, двигательные компоненты всех полученных зрительных, слуховых и других ощущений связываются в первую очередь. Слияние в образ других элементов — зрительных, слуховых и т. д. происходит позже.

За последние годы получено много фактов в исследованиях на животных и на взрослых людях, которые показывают, что именно в двигательной области объединяются нервные импульсы со всех органов чувств. Кстати сказать, эту очень важную роль двигательной области Сеченов тоже предвидел: он писал о том, что «мышечное чувство», по-видимому, имеет связующую функцию, благодаря чему становится возможным объединение всех других ощущений в комплексы.

Теперь мы знаем секрет влияния 20 двигательных условных связей. Он заключается в том, что мышечные ощущения, возникающие при действиях с предметом, усиливают все другие ощущения и помогают связать их в единое целое. Именно в этом сила тех 20 двигательных связей, которые мы так часто вспоминали и будем вспоминать еще.

Обычно мы ищем отражение формирующихся представлений и понятий ребенка в его словах. Но, оказывается, есть еще один показатель — очень выразительный и точный — рисунок.

На первый взгляд рисунок кажется прямым копированием действительности, т. е. формой передачи непосредственных ощущений, которые человек получает от реальных предметов. Но это только на первый взгляд, Способность соотнести реальный объект — дом, человека, цветок — с его линейным одномерным изображением на плоскости бумаги требует довольно высокой степени абстрагирования.

Многие ученые занимались вопросом о том, как ребенок научается понимать рисунок, показываемый ему, и как он начинает рисовать сам.

Малыш конца первого — начала второго года жизни еще не понимает изображений. Он стремится скомкать бумагу, тянет ее в рот и не обращает никакого внимания на сам рисунок. Нужно много раз показать картинку, назвать нарисованный на ней предмет, чтобы ребенок начал различать его. Только после того как дети научатся «читать» чужой рисунок, они начинают делать попытки рисовать сами.

Важно отметить, что животные не обладают способностью к изобразительной деятельности. В литературе есть описания случаев, когда шимпанзе рисовали красками («картины» их носили абстрактный характер, это были просто цветовые пятна). Это, конечно, лишь подражание действиям человека: глядя, как человек обмакивает кисть в краску и наносит ею мазки, обезьяна делает то же самое. Совершенно так же и первые каракули ребенка не есть еще изобразительная деятельность в полном смысле слова — это манипуляции с карандашом подражательного характера.

Приблизительно в два с половиной года ребенок начинает рисовать на самом деле: из его каракуль выделяются контуры человечков — круг вместо головы, палочки вместо ног (рис. 22 и 23).

Fig. 22. Мама. Лили К. (2 года 7 мес.).

Fig. 23. Папа. Юра З. (2 года 2 мес.).

Это всегда изображения отдельных людей: мама, папа, баба. Иногда на одном рисунке рядом появляется несколько «головоногов», но каждый из них все та же мама или тот же папа. Не случайно эта фаза рисования совпадает с периодом, когда у ребенка уже достаточно развита назывательная функция слова: он выделяет отдельные предметы и усваивает их названия. Порой (правда, довольно редко) дети рисуют в этом возрасте и животных (рис. 24). Тут схема другая: туловище и много ног, головы обычно нет вовсе или она очень незаметная.

Fig. 24. Кошка. Юра 3. (2 года 2 мес.).

Несколько позже — в 2 года 10 месяцев — 3 года в рисунках малышей выявляются уже II и III степени обобщения. Так, «мама» означает не только собственную маму малыша, но становится понятием. Это отражается и в рисунках. «Я и Люба 6 мамами» (рис. 25) рисует Зоя 2 лет 10 месяцев,

Fig. 25. Я и Люба с мамами. Зоя П. (2 года 10 мес.).

а Лиля 3 лет изобразила кошку с котятами (рис. 26).

Fig. 26. Мурка с котятами. Лиля К. (3 года).

На этих рисунках показаны уже не отдельные объекты, а матери с детьми У более старших детей можно видеть в рисунках и более высокие степени обобщения. К IV степени обобщения относится формирование понятий о том, что хорошо, что плохо, что красиво, а что — нет и т. п. Посмотрите, как это выявляется в рисунках ребятишек.

Андрюша 4 лет изобразил себя и брата Сашу за обедом (рис. 27). Сам художник, как видите, пай-мальчик: он хорошо сидит и ест аккуратно, а Саша машет руками и обливается киселем — фу!

Fig. 27. Мы с Сашей обедаем. Андрюша К. (4 года).

Гера 5 лет в своем рисунке (рис. 28) показал, что он не жадный (т. е. хороший мальчик): дает приятелю Кольке лизнуть мороженое.

Fig. 28. Я не жадный, даю Кольке лизнуть мороженое. Гера Р. (5 лет).

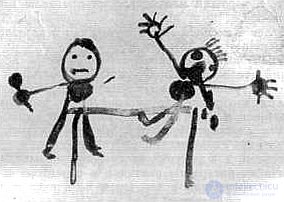

Женя 5 лет 4 месяцев свой рисунок так и назвал: «Стыдно бить маленького» (рис. 29).

Fig. 29. Стыдно бить маленького. Женя Ф. (5 лет 4 мес.).

В картинах четырех-пятилетних художников преобладают изображения отношений между людьми, событий, в которых очень ярко выступают положительные или отрицательные черты поведения изображаемых персонажей. Сформировавшиеся понятия ребенок в этом возрасте даже легче выражает через рисунок, чем словами. Например, тот же Андрюша затрудняется объяснить словами, чем плохо поведение его братишки Саши за столом, а в рисунке он показал это очень наглядно.

Чрезвычайно интересны различия в характере отвлеченного словесного мышления у девочек и мальчиков и отражение этих различий в их рисунках.

Как-то мы проанализировали большое количество рисунков на темы «Что ты видел в лесу», «Дорога из дома в детский сад» и на свободные темы. Бросается в глаза такая особенность всех рисунков девочек (в возрасте от пяти до семи лет): на первом плане изображена сама девочка — одна, с мамой, с подругами; она собирает ягоды, рвет цветы, идет по улице и т. д. Мальчики рисуют охотника с собакой в лесу, дот, который там видели, линию высоковольтной передачи, транспорт на улице — себя они не рисуют. По видимому, это свидетельствует о более раннем развитии у них способности абстрагироваться от своей личности. Это подтверждается и тем, что у мальчиков очень рано появляются рисунки типа плана, схемы.

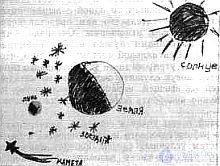

Посмотрите на рисунок Володи А. 6 лет (рис. 30) «Космос» — как много общих понятий вложено в этот маленький листочек бумаги! И о космическом пространстве как таковом, и о положении Земли в отношении других планет и звезд, и о том, как «получается» день и ночь!

Fig. 30. Космос. Володя А. (6 лет).

Среди множества рисунков девочек не оказалось ни одного типа плана или схематического изображения отношений, а у мальчиков такие рисунки встречаются то и дело. Причем рисунки девочек отличаются очень тщательной передачей деталей, стремлением представить все красиво. В этом отношении любопытны рисунки Тани С. 7 лет и ее брата Лени С. 6 лет — они оба только начали заниматься музыкой и оба нарисовали свое пианино (рис. 31 и 32).

Fig. 31. Наше пианино. Леня С. (6 лет).

Fig. 32. Наше пианино. Таня С. (7 лет).

Таня очень хорошо передала внешнюю сторону изображаемого, даже букет цветов на пианино и, конечно, себя во вдохновенной позе. Леню не занимала внешняя красивость — он изобразил внутреннее устройство инструмента так, как его понимает.

Вероятно, нельзя ставить вопрос о том, что мальчики думают лучше. По вполне можно говорить, что характер мышления у девочек и мальчиков разный и каждый имеет свои преимущества и свои недостатки. На основании изучения детских рисунков мы считаем возможным утверждать, что мальчики в массе ближе стоят к «мыслительному» типу нервной деятельности, а девочки — к «художественному». При этом нужно подчеркнуть, что если среди мальчиков встречались все же такие, которых можно было отнести к художественному типу, то среди девочек мы не нашли пи одной с выраженным мыслительным типом. Это обстоятельство нам представляется очень важным в практическом отношении. Очевидно, что в программе занятий с мальчиками нужно особое внимание уделять воспитанию первой сигнальной системы для того, чтобы избежать формирования утрированного мыслительного типа.

Итак, рисунки детей могут служить очень ценным методом изучения особенностей их высшей нервной деятельности, на основании чего возможно подобрать более подходящие приемы воспитания.

…В заключение этой главы хочется еще раз подчеркнуть: понимание речи есть работа головного мозга, имеющая в своей основе выработку систем условных связей. Ребенок научается понимать, что каждый предмет имеет название; что каждое свойство предмета — большой он или маленький, зеленый или

белый, мягкий или твердый и т. д. — имеет название; что всякое действие — пошел, взял, уронил, съел — тоже имеет название. Малыш узнает, что предметы и действия объединяются в группы, имеющие определенное словесное обозначение: каша, яблоко, пирог — еда; складывание кубиков, подбрасывание мячика, бегание вперегонки — игра. Усложняются и отношения предметов, их причинные связи, которые ребенок научается понимать. И все это результат выработки систем условных связей. Нужно иметь в виду, что эта огромная работа по формированию систем связей может совершаться успешно лишь в том случае, если окружающие ребенка взрослые понимают, какие условия благоприятны для нее, и стараются эти условия создать и тем самым обеспечить правильное развитие речи своего ребенка.

Comments

To leave a comment

Pedagogy and didactics

Terms: Pedagogy and didactics