Lecture

This chapter examines the possibilities of parallel execution of transactions by several users, i.e. property (I) - isolation of transactions.

Modern DBMS are multi-user systems, i.e. allow parallel simultaneous work of a large number of users. At the same time, users should not interfere with each other. Because the logical unit of work for the user is a transaction, then the work of the DBMS should be organized so that the user has the impression that their transactions are performed independently of the transactions of other users.

The simplest and most obvious way to provide such an illusion to the user is to build all incoming transactions into a single queue and execute them strictly in turn. This method is not suitable for obvious reasons - the advantage of parallel work is lost. Thus, transactions must be performed simultaneously, but so that the result is the same as if the transactions were executed in turn. The difficulty is that if no special measures are taken, the data modified by one user can be changed by another user’s transaction before the first user’s transaction ends. As a result, at the end of the transaction, the first user will see not the results of his work, but what is unknown.

One of the ways (not the only one) to ensure the independent parallel operation of several transactions is the lock method.

A transaction is considered as a sequence of elementary atomic operations. The atomicity of a separate elementary operation is that the DBMS guarantees that, from the user's point of view, two conditions will be met:

For example, elementary transaction operations will read a data page from a disk or write a data page to a disk (the data page is the minimum unit for DBMS disk operations). Condition 2 is actually a logical condition, since in reality, the system can perform several different elementary operations at the same time. For example, data can be stored on several physically different disks and read / write operations on these disks can be performed simultaneously.

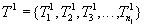

The elementary operations of various transactions can be performed in an arbitrary order (of course, within each transaction, the sequence of elementary operations of this transaction is strictly defined). For example, if there are several transactions consisting of a sequence of elementary operations:

,

,

,

,

then the real sequence in which the DBMS performs these transactions may be, for example, like this:

.

.

Definition 1 . A set of several transactions whose atomic operations alternate with each other is called a mixture of transactions .

Definition 2 . The sequence in which elementary operations of a given set of transactions are performed is called the schedule for starting a set of transactions.

Remark Obviously, for a given set of transactions there may be several (generally speaking, quite a lot) different launch schedules.

Ensuring user isolation, therefore, comes down to choosing the appropriate (in some sense the right) transaction launch schedule. At the same time, the launch schedule should be optimal in a certain sense, for example, to give the minimum average transaction time for each user.

Next, we will clarify the concept of "correct" graphics and make some comments on optimality.

How can transactions of different users interfere with each other? There are three main problems of concurrency:

Consider in detail these problems.

Consider two transactions, A and B, running according to some graphs. Let transactions work with some database objects, such as table rows. String read operation  will denote

will denote  where

where  - read value. Value write operation

- read value. Value write operation  in line

in line  will denote

will denote  .

.

Two transactions, in turn, write some data to the same row and commit the changes.

| Transaction A | Time | Transaction B |

|---|---|---|

Reading  |  | --- |

| --- |  | Reading  |

Record  |  | --- |

| --- |  | Record  |

| Commit transaction |  | --- |

| --- |  | Commit transaction |

| Loss of update result |

Result . After completing both transactions, the string  contains value

contains value  entered by a later transaction B. Transaction A knows nothing about the existence of transaction B, and naturally expects that in line

entered by a later transaction B. Transaction A knows nothing about the existence of transaction B, and naturally expects that in line  contains value

contains value  . Thus, transaction A has lost the results of its work.

. Thus, transaction A has lost the results of its work.

Transaction B modifies the data in the row. After this, transaction A reads the changed data and works with it. Transaction B rolls back and restores old data.

| Transaction A | Time | Transaction B |

|---|---|---|

| --- |  | Reading  |

| --- |  | Record  |

Reading  |  | --- |

Work with read data  |  | --- |

| --- |  | Transaction rollback  |

| Commit transaction |  | --- |

| Work with dirty data |

What did transaction A work with?

Result . Transaction A used data in its work that is not in the database. Moreover, transaction A used data that is not there, and was not in the database! Indeed, after the rollback of transaction B, the situation should recover, as if transaction B had never been executed at all. Thus, the results of transaction A are incorrect, since she worked with data that was not in the database.

The problem of incompatible analysis includes several different options:

Transaction A reads the same line twice. Between these readings is wired transaction B, which changes the values in the string.

| Transaction A | Time | Transaction B |

|---|---|---|

Reading  |  | --- |

| --- |  | Reading  |

| --- |  | Record  |

| --- |  | Commit transaction |

Re-read  |  | --- |

| Commit transaction |  | --- |

| Unrepeatable read |

Transaction A does not know anything about the existence of Transaction B, and, since she herself does not change the value in the string, then expects that after re-reading the value will be the same.

Result . Transaction A operates on data that, in terms of Transaction A, changes spontaneously.

The effect of fictitious elements is somewhat different from previous transactions in that here in one step quite a lot of operations are performed — reading several lines at once that satisfy a certain condition.

Transaction A doubles to fetch rows with the same condition. Transaction B is inserted between the samples, which adds a new line that satisfies the selection condition.

| Transaction A | Time | Transaction B |

|---|---|---|

Selection of rows that satisfy the condition  . . (N rows selected) |  | --- |

| --- |  | Insert a new line that satisfies the condition  . . |

| --- |  | Commit transaction |

Selection of rows that satisfy the condition  . . (N + 1 rows selected) |  | --- |

| Commit transaction |  | --- |

| There are lines that were not there before |

Transaction A does not know anything about the existence of Transaction B, and, since she herself does not change anything in the database, she expects that the same lines will be selected after re-selection.

Result . Transaction A in two identical rows of samples received different results.

The effect of the incompatible analysis itself is also different from the previous examples in that there are two transactions in the mix - one long and the other short.

A long transaction performs some analysis on the entire table, for example, it calculates the total amount of money in the accounts of bank customers for the chief accountant. Let all accounts have the same amount, for example, for $ 100. A short transaction at this moment transfers $ 50 from one account to another so that the total amount for all accounts does not change.

| Transaction A | Time | Transaction B |

|---|---|---|

Reading account  and summation. and summation.  |  | --- |

| --- |  | Withdrawing money from an account  . .  |

| --- |  | Putting money into the account  . .  |

| --- |  | Commit transaction |

Reading account  and summation. and summation.  |  | --- |

Reading account  and summation. and summation.  |  | --- |

| Commit transaction |  | --- |

| The sum of $ 250 for all accounts is incorrect - must be $ 300 |

Result . Although transaction B did everything right - the money was transferred without loss, but as a result, transaction A calculated the wrong total amount.

Because money transfer transactions are usually continuous, then in this situation we should expect that the chief accountant will never know how much money is in the bank.

So, the analysis of the problems of parallelism shows that if no special measures are taken, then when working in a mixture, the property (AND) of transactions - isolation - is violated. Transactions really prevent each other from getting the right results.

However, not all transactions interfere with each other. Obviously, transactions do not interfere with each other if they access different data or are executed at different times .

Definition 3 . Transactions are called competing if they intersect in time and access the same data.

As a result of competition for data between transactions, data access conflicts occur. There are the following types of conflicts:

Conflicts such as RR (Reading - Reading) are absent, because reading data does not change.

Other problems of parallelism (phantoms and actually incompatible analysis) are more complex, because their fundamental difference is that they cannot arise when working with one object. These problems require that transactions work with whole data sets .

Definition 4 . The schedule for starting a set of transactions is called sequential if the transactions are executed strictly in turn, i.e. elementary transaction transactions do not alternate with each other.

Definition 5 . If the schedule of starting a set of transactions contains alternating elementary transactions of transactions, then this schedule is called alternating .

When performing a sequential schedule, it is guaranteed that the transactions are carried out correctly, i.e. with a consistent schedule, transactions do not “feel” each other’s presence.

Definition 6 . Two graphs are called equivalent if, when they are executed, the same result is obtained, regardless of the initial state of the database .

Definition 7 . A transaction start schedule is called true ( serializable ) if it is equivalent to any sequential schedule.

Remark By performing two different sequential (and, therefore, valid) graphs containing the same set of transactions, different results can be obtained. Indeed, let transaction A consist in the action “Add X to 1”, and transaction B - “Double X”. Then the successive graph {A, B} will give the result 2 (X + 1), and the successive graph {B, A} will give the result 2X + 1. Thus, there may be several valid transaction start schedules that lead to different results for the same initial state of the database.

The task of providing users with isolated work is not reduced simply to finding the right (serial) schedules for transaction launches. If this were sufficient, then the best would be the simplest way to serialize - put transactions in a common queue as they arrive and perform strictly sequentially. In this way, the correct (serial) schedule will be automatically obtained. The problem is that this schedule will not be optimal in terms of overall system performance. It turns out a situation in which opposing forces struggle - on the one hand, the desire to ensure seriality by deteriorating the overall performance, on the other hand, the desire to improve overall efficiency by worsening seriality.

We considered one extreme case (execution of transactions in turn). Consider another extreme case — try to achieve an optimal schedule — that is, graphics with maximum transaction performance. To do this, you first need to clarify the concept of "optimality". With each possible transaction launch schedule, we can associate the value of some cost function. As a value function, you can take, for example, the total execution time of all transactions in a set. The execution time of a single transaction is counted from the moment when the transaction occurred and until the moment when the transaction performed its last elementary operation. This time consists of the following components:

The best schedule will be, giving a minimum of the cost function. Obviously, the optimal launch schedule depends on the choice of the cost function, i.e. a schedule that is optimal from the point of view of some criteria (for example, from the point of view of the reduced cost function) will not be optimal from the point of view of other criteria (for example, from the point of view of achieving the fastest possible start of each transaction).

Consider the following hypothetical situation. Предположим, что нам заранее на некоторый промежуток времени наперед известно, какие транзакции в какие моменты поступят, т.е. заранее известна вся будущая смесь транзакций и моменты поступления каждой транзакции :

Транзакция  поступит в момент

поступит в момент  .

.

Транзакция  поступит в момент

поступит в момент  .

.

...

Транзакция  поступит в момент

поступит в момент  .

.

В этом случае, т.к. набор всех транзакций заранее известен, теоретически можно перебрать все возможные варианты графиков запусков (их конечное число, хотя и очень большое), и выбрать из них те графики, которые, во-первых, правильные, а во-вторых, оптимальны по выбранному критерию. В этом случае оптимальный график запуска транзакций достижим.

В реальной ситуации, однако, неизвестно не только какие транзакции будут поступать в какие моменты времени, но и неизвестна длительность периода времени, охватывающего набор транзакций. Реально, система может непрерывно работать несколько дней или месяцев и в этом случае набором транзакций будет набор всех транзакций за этот период. С другой стороны, прекращение работы сервера может произойти в любой момент либо по команде администратора системы, либо в результате сбоя. Необходимо, следовательно, чтобы система работала так, чтобы к любому моменту времени набор выполненных и выполняющихся в этот момент транзакций был бы правильным и не слишком далек от оптимального.

Because транзакции не мешают друг другу, если они обращаются к разным данным или выполняются в разное время, то имеется два способа разрешить конкуренцию между поступающими в произвольные моменты транзакциями:

Первый метод - "притормаживание" транзакций - реализуется путем использованием блокировок различных видов или метода временных меток.

Второй метод - предоставление разных версий данных - реализуется путем использованием данных из журнала транзакций.

Основная идея блокировок заключается в том, что если для выполнения некоторой транзакции необходимо, чтобы некоторый объект не изменялся без ведома этой транзакции, то этот объект должен быть заблокирован, т.е. доступ к этому объекту со стороны других транзакций ограничивается на время выполнения транзакции, вызвавшей блокировку.

Различают два типа блокировок:

Если транзакция A блокирует объект при помощи X-блокировки, то всякий доступ к этому объекту со стороны других транзакций отвергается.

Если транзакция A блокирует объект при помощи S-блокировки, то

Правила взаимного доступа к заблокированным объектам можно представить в виде следующей матрицы совместимости блокировок . Если транзакция A наложила блокировку на некоторый объект, а транзакция B после этого пытается наложить блокировку на этот же объект, то успешность блокирования транзакцией B объекта описывается таблицей:

| Транзакция B пытается наложить блокировку: | ||

| Транзакция A наложила блокировку: | S-блокировку | X-блокировку |

| S-блокировку | Yes | NOT (Конфликт RW) |

|---|---|---|

| X-блокировку | NOT (Конфликт WR) | NOT (Конфликт WW) |

Таблица 1 Матрица совместимости S- и X-блокировок

Три случая, когда транзакция B не может блокировать объект, соответствуют трем видам конфликтов между транзакциями.

Доступ к объектам базы данных на чтение и запись должен осуществляться в соответствии со следующим протоколом доступа к данным :

Рассмотрим, как будут себя вести транзакции, вступающие в конфликт при доступе к данным, если они подчиняются протоколу доступа к данным.

Две транзакции по очереди записывают некоторые данные в одну и ту же строку и фиксируют изменения.

| Транзакция A | Time | Транзакция B |

|---|---|---|

S-блокировка  - успешна - успешна |  | --- |

Чтение  |  | --- |

| --- |  | S-блокировка  - успешна - успешна |

| --- |  | Чтение  |

X-блокировка  - отвергается - отвергается |  | --- |

| Ожидание… |  | X-блокировка  - отвергается - отвергается |

| Ожидание… |  | Ожидание… |

| Ожидание… | Ожидание… |

Обе транзакции успешно накладывают S-блокировки и читают объект  . Транзакция A пытается наложить X-блокирокировку для обновления объекта

. Транзакция A пытается наложить X-блокирокировку для обновления объекта  . Блокировка отвергается, т.к. an object

. Блокировка отвергается, т.к. an object  already S-locked by transaction B. Transaction A goes to the wait state until transaction B releases the object. Transaction B, in turn, tries to impose X-blocking to update the object.

already S-locked by transaction B. Transaction A goes to the wait state until transaction B releases the object. Transaction B, in turn, tries to impose X-blocking to update the object. . The lock is rejected because an object

. The lock is rejected because an object  already S-locked by transaction A. Transaction B enters a wait state until transaction A releases the object.

already S-locked by transaction A. Transaction B enters a wait state until transaction A releases the object.

Result . Both transactions await each other and cannot proceed. There was a deadlock situation .

Transaction B modifies the data in the row. After this, transaction A reads the changed data and works with it. Transaction B rolls back and restores old data.

| Transaction A | Time | Transaction B |

|---|---|---|

| --- |  | S-блокировка  - успешна - успешна |

| --- |  | Чтение  |

| --- |  | X-блокировка  - успешна - успешна |

| --- |  | Record  |

S-блокировка  - отвергается - отвергается |  | --- |

| Ожидание… |  | Откат транзакции  (Блокировка снимается) |

S-блокировка  - успешна - успешна |  | --- |

Чтение  |  | --- |

Работа с прочитанными данными  |  | --- |

| --- |  | --- |

| Фиксация транзакции |  | --- |

| All right |

Результат . Транзакция A притормозилась до окончания (отката) транзакции B. После этого транзакция A продолжила работу в обычном режиме и работала с правильными данными. Конфликт разрешен за счет некоторого увеличения времени работы транзакции A (потрачено время на ожидание снятия блокировки транзакцией B).

Транзакция A дважды читает одну и ту же строку. Между этими чтениями вклинивается транзакция B, которая изменяет значения в строке.

| Транзакция A | Time | Транзакция B |

|---|---|---|

S-блокировка  - успешна - успешна |  | --- |

Чтение  |  | --- |

| --- |  | X-блокировка  - отвергается - отвергается |

| --- |  | Ожидание… |

Re-read  |  | Expectation… |

| Transaction commit (Lock unlocked) |  | Expectation… |

| --- |  | X lock  is successful is successful |

| --- |  | Record  |

| --- |  | Transaction commit (Lock unlocked) |

| All right |

Result . Transaction B slowed down until the end of transaction A. As a result, transaction A twice reads the same data correctly. After the end of transaction A, transaction B continued to work as usual.

Transaction A doubles to fetch rows with the same condition. Transaction B is inserted between the samples, which adds a new line that satisfies the selection condition.

| Transaction A | Time | Transaction B |

|---|---|---|

S-lock strings that satisfy the condition  . . (Locked n lines) |  | --- |

Selection of rows that satisfy the condition  . . (N rows selected) |  | --- |

| --- |  | Insert a new line that satisfies the condition  . . |

| --- |  | Commit transaction |

S-lock strings that satisfy the condition  . . (Locked n + 1 row) |  | --- |

Selection of rows that satisfy the condition  . . (Отобрано n+1 строк) |  | --- |

| Фиксация транзакции |  | --- |

| Появились строки, которых раньше не было |

Результат . Блокировка на уровне строк не решила проблему появления фиктивных элементов.

Длинная транзакция выполняет некоторый анализ по всей таблице, например, подсчитывает общую сумму денег на счетах клиентов банка для главного бухгалтера. Пусть на всех счетах находятся одинаковые суммы, например, по $100. Короткая транзакция в этот момент выполняет перевод $50 с одного счета на другой так, что общая сумма по всем счетам не меняется.

| Транзакция A | Time | Транзакция B |

|---|---|---|

S-блокировка счета  - успешна - успешна |  | --- |

Чтение счета  и суммирование. и суммирование.  |  | --- |

| --- |  | X-блокировка счета  - успешна - успешна |

| --- |  | Снятие денег со счета  . .  |

| --- |  | X-блокировка счета  - отвергается - отвергается |

| --- |  | Ожидание… |

S-блокировка счета  - успешна - успешна |  | Ожидание… |

Чтение счета  и суммирование. и суммирование.

|  | Ожидание… |

S-блокировка счета  - отвергается - отвергается |  | Ожидание… |

| Ожидание… |  | Ожидание… |

| Ожидание… | Ожидание… |

Результат . Обе транзакции ожидают друг друга и не могут продолжаться. Возникла ситуация тупика .

Итак, при использовании протокола доступа к данным с использованием блокировок часть проблем разрешилось (не все), но возникла новая проблема - тупики:

Общий вид тупика ( dead locks ) следующий:

| Транзакция A | Time | Транзакция B |

|---|---|---|

Блокировка объекта  - успешна - успешна |  | --- |

| --- |  | Блокировка объекта  -успешна -успешна |

Блокировка объекта  - конфликтует с блокировкой, наложенной транзакцией B - конфликтует с блокировкой, наложенной транзакцией B |  | --- |

| Ожидание… |  | Блокировка объекта  - конфликтует с блокировкой, наложенной транзакцией A - конфликтует с блокировкой, наложенной транзакцией A |

| Ожидание… |  | Ожидание… |

| Ожидание… | Ожидание… |

Как видно, ситуация тупика может возникать при наличии не менее двух транзакций, каждая из которых выполняет не менее двух операций. На самом деле в тупике может участвовать много транзакций, ожидающих друг друга.

Because нормального выхода из тупиковой ситуации нет, то такую ситуацию необходимо распознавать и устранять. Методом разрешения тупиковой ситуации является откат одной из транзакций (транзакции-жертвы) так, чтобы другие транзакции продолжили свою работу. После разрешения тупика, транзакцию, выбранную в качестве жертвы можно повторить заново.

Можно представить два принципиальных подхода к обнаружению тупиковой ситуации и выбору транзакции-жертвы:

Первый подход характерен для так называемых настольных СУБД (FoxPro и т.п.). Этот метод является более простым и не требует дополнительных ресурсов системы. Для транзакций задается время ожидания (или число попыток), в течение которого транзакция пытается установить нужную блокировку. Если за указанное время (или после указанного числа попыток) блокировка не завершается успешно, то транзакция откатывается (или генерируется ошибочная ситуация). За простоту этого метода приходится платить тем, что транзакции-жертвы выбираются, вообще говоря, случайным образом. В результате из-за одной простой транзакции может откатиться очень дорогая транзакция, на выполнение которой уже потрачено много времени и ресурсов системы.

Второй способ характерен для промышленных СУБД (ORACLE, MS SQL Server и т.п.). В этом случае система сама следит за возникновением ситуации тупика, путем построения (или постоянного поддержания) графа ожидания транзакций. Граф ожидания транзакций - это ориентированный двудольный граф, в котором существует два типа вершин - вершины, соответствующие транзакциям, и вершины, соответствующие объектам захвата. Ситуация тупика возникает, если в графе ожидания транзакций имеется хотя бы один цикл. Одну из транзакций, попавших в цикл, необходимо откатить, причем, система сама может выбрать эту транзакцию в соответствии с некоторыми стоимостными соображениями (например, самую короткую, или с минимальным приоритетом и т.п.).

Как видно из анализа поведения транзакций, при использовании протокола доступа к данным не решается проблема фантомов. Это происходит оттого, что были рассмотрены только блокировки на уровне строк. Можно рассматривать блокировки и других объектов базы данных:

Кроме того, можно блокировать индексы, заголовки таблиц или другие объекты.

Чем крупнее объект блокировки, тем меньше возможностей для параллельной работы. Достоинством блокировок крупных объектов является уменьшение накладных расходов системы и решение проблем, не решаемых с использованием блокировок менее крупных объектов. Например, использование монопольной блокировки на уровне таблицы, очевидно, решает проблему фантомов.

Современные СУБД, как правило, поддерживают минимальный уровень блокировки на уровне строк или страниц. (В старых версиях настольной СУБД Paradox поддерживалась блокировка на уровне отдельных полей.).

При использовании блокировок объектов разной величины возникает проблема обнаружения уже наложенных блокировок. Если транзакция A пытается заблокировать таблицу, то необходимо иметь информацию, не наложены ли уже блокировки на уровне строк этой таблицы, несовместимые с блокировкой таблицы. Для решения этой проблемы используется протокол преднамеренных блокировок , являющийся расширением протокола доступа к данным. Суть этого протокола в том, что перед тем, как наложить блокировку на объект (например, на строку таблицы), необходимо наложить специальную преднамеренную блокировку ( блокировку намерения ) на объекты, в состав которых входит блокируемый объект - на таблицу, содержащую строку, на файл, содержащий таблицу, на базу данных, содержащую файл. Тогда наличие преднамеренной блокировки таблицы будет свидетельствовать о наличии блокировки строк таблицы и для другой транзакции, пытающейся блокировать целую таблицу не нужно проверять наличие блокировок отдельных строк. Более точно, вводятся следующие новые типы блокировок:

IS, IX and SIX locks should overlap with complex database objects (tables, files). In addition, block types S and X can be superimposed on complex objects. For complex objects (for example, for a database table), the lock compatibility table has the following form:

| Transaction B is trying to impose a lock on the table: | |||||

| Transaction A has imposed a lock on the table: | IS | S | Ix | Six | X |

| IS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | Yes | Yes | Not | Not | Not |

| Ix | Yes | Not | Yes | Not | Not |

| Six | Yes | Not | Not | Not | Not |

| X | Not | Not | Not | Not | Not |

Table 2 Extended Lock Compatibility Table

A more precise wording of the deliberate blocking protocol for data access is as follows:

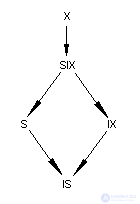

The concept of the relative strength of locks can be described using the following priority diagram (above - stronger locks, below - weaker ones):

Table 3 Lock Preference Chart

Remark The deliberate locking protocol does not explicitly determine which locks should be imposed on the parent object when the child is locked. For example, if you intend to set an S-lock on a table row, you can impose any of the IS, S, IX, SIX, X locks on a table that includes this row. If you intend to specify an X-row lock, you can impose any of the locks on the table IX, SIX, X.

Let's see how the problem of fictitious elements (phantoms) is solved using a deliberate locking protocol for data access.

Transaction A doubles to fetch rows with the same condition. Transaction B is inserted between the samples, which adds a new line that satisfies the selection condition.

Transaction B must impose an IX lock on the table, or a stronger one (SIX or X), before attempting to insert a new line. Then, transaction A, in order to prevent a possible conflict, should impose such a lock on the table that would not allow transaction B to impose an IX-lock. According to the lock compatibility table, we determine that transaction A should impose on table S, or SIX, or X-lock. (IS lock is not enough, because this lock allows transaction B to impose an IX lock for subsequent insertion of rows).

| Transaction A | Time | Transaction B |

|---|---|---|

| S-lock the table (with the aim to block the rows later) - successful |  | --- |

S-lock rows that satisfy the condition  . . (Locked n lines) |  | --- |

Selection of rows that satisfy the condition  . . (N rows selected) |  | --- |

| --- |  | IX-table lock (with the aim to insert rows later) - is rejected due to a conflict with the S-lock imposed by transaction A |

| --- |  | Expectation… |

| --- |  | Expectation… |

S-lock rows that satisfy the condition  . . (Locked n lines) |  | Expectation… |

Selection of rows that satisfy the condition  . . (N rows selected) |  | Expectation… |

| Commit transaction - locks are released |  | Expectation… |

| --- |  | IX-table lock (with the goal to insert rows later) is successful |

| --- |  | Insert a new line that satisfies the condition  . . |

| --- |  | Commit transaction |

| Transaction A reads the same rowset twice All right |

Result . The problem of bogus elements (phantoms) is solved if transaction A uses a deliberate S-lock or a stronger one.

Remark Because If transaction A is only going to read the rows of a table, then the minimum necessary condition in accordance with the deliberate locking protocol is an intentional IS-lock of the table. However, this type of blocking does not prevent the appearance of phantoms. Thus, transaction A can be run with different levels of isolation - preventing or allowing phantoms to appear. Moreover, both methods of launching correspond to the protocol of deliberate locks for data access.

Another way to block is to block not the database objects, but the conditions that the objects can satisfy. Such locks are called predicate locks .

Since any operation on a relational database is defined by some condition (that is, it indicates not a specific set of database objects over which the operation needs to be performed, but a condition that the objects of this set must satisfy), then S or X would be a convenient way -blocking this particular condition. However, when trying to use this method in a real DBMS, it becomes difficult to determine the compatibility of various conditions. Indeed, in SQL, conditions with subqueries and other complex predicates are allowed. The compatibility problem is relatively easily solved for the case of simple conditions that have the form:

{ Attribute name {= | <> | > | | > = | <| <=} Value }

[{ OR | AND } { Attribute name {= | <> | > | | > = | <| <=} Value }., ..]

The problem of fictitious elements (phantoms) is easily solved using predicate locks, since The second transaction cannot insert new rows that satisfy the condition already blocked.

Note that locking the entire table in any mode is actually a predicate lock, since Each table has a predicate that determines which rows are contained in the table and the table lock is a lock of the predicate of this table.

An alternative transaction serialization method that works well in rare transaction conflict situations and does not require the construction of a transaction waiting graph based on the use of timestamps .

The basic idea of the method is as follows: if transaction A began before transaction B, then the system provides such a mode of execution as if A had been completely completed before the start of B.

For this, each transaction T is assigned a timestamp t corresponding to the start time T. When performing an operation on a database object r, transaction T marks it with its timestamp and type of operation (read or change).

Before performing an operation on an object r, transaction B performs the following actions:

As a result, the system provides such work in which, in the event of conflicts, a younger transaction is always rolled back (which began later).

An obvious disadvantage of the timestamp method is that a more expensive transaction that started later on a cheaper one can roll back.

Other disadvantages of the timestamp method are potentially more frequent transaction rollbacks than in the case of locks. This is due to the fact that transaction conflict is determined more roughly.

The use of locks guarantees the seriality of plans to perform a mixture of transactions at the expense of a general slowing down of work - conflicting transactions are waiting for the transaction that first blocked some object to not release it. You cannot do without locks if all transactions change data. But if in a mixture of transactions there are both transactions that modify the data, and only those that read the data, you can use an alternative seriality mechanism that is free from the drawbacks of the lock method. This method consists in the fact that transactions that read the data are provided with their own version of the data, which was available at the moment of the beginning of the reading transaction. In this case, the transaction does not impose locks on the read data, and, therefore, does not block other transactions that modify the data. Such a mechanism is called a versioning mechanism and consists in using a transaction log to generate different versions of data.

The transaction log is designed to perform a rollback operation if the transaction is unsuccessful or to recover data after a system failure. The transaction log contains old copies of data modified by transactions.

Briefly, the essence of the method is as follows:

Consider how to solve the problem of incompatible analysis using the mechanism of versioning.

A long transaction performs some analysis on the entire table, for example, it calculates the total amount of money in the accounts of bank customers for the chief accountant. Let all accounts have the same amount, for example, for $ 100. A short transaction at this moment transfers $ 50 from one account to another so that the total amount for all accounts does not change.

| Transaction A | Time | Transaction B |

|---|---|---|

SCN account verification  - SCN transaction is greater than SCN account. - SCN transaction is greater than SCN account. Reading account  no blocking and summation. no blocking and summation.  |  | --- |

| --- |  | X-block account  - successful - successful |

| --- |  | Withdrawing money from an account  . .  |

| --- |  | X-block account  - successful - successful |

| --- |  | Putting money into the account  . .  |

| --- |  | Commit transaction (Unlocking) |

SCN account verification  - SCN transaction is greater than SCN account. - SCN transaction is greater than SCN account. Reading account  no overlap blocking and summarization. no overlap blocking and summarization.  |  | --- |

SCN account verification  - SCN transactions LESS SCN accounts. - SCN transactions LESS SCN accounts. Reading old invoice option  and summation. and summation.  |  | --- |

| Commit transaction |  | --- |

| The amount in the accounts counted correctly. |

Result . Transaction A, which began first, does not inhibit competing transaction B. When a conflict is detected (read by transaction A of a modified account 3), transaction A is provided with its own version of the data that was at the start of transaction A.

The concept of the ability to streamline was first proposed by Eswaran [50].

In this paper, a two-phase blocking protocol was proposed:

The transactions used in this protocol are not differentiated by type and are considered exclusive. The data access protocols described above using S- and X-locks and the deliberate-locking protocol are modifications of the two-phase locking protocol for the case when the locks are of different types.

Eswaran formulated the following theorem:

Eswaran's theorem . If all transactions in the mix obey the two-phase lock protocol, then for all alternate launch schedules, there is a possibility of sequencing.

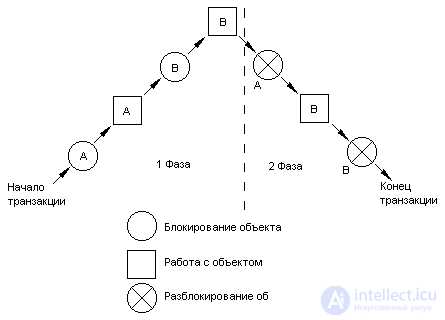

The protocol is called biphasic because it is characterized by two phases:

The operation of the transaction may look approximately as shown:

Figure 1 The operation of the transaction on the two-phase lock protocol

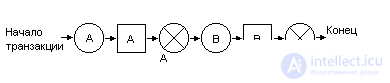

The following figure shows an example of a transaction that does not obey the two-phase lock protocol:

Figure 2 A transaction that does not obey the two-phase locking protocol

In practice, as a rule, the second phase is reduced to a single transaction completion operation (or transaction rollback) with the simultaneous release of all locks.

If some transaction A does not obey the two-phase locking protocol (and, consequently, consists of at least two locking and unlocking operations), then another transaction B can be constructed, which, when executed alternately with A, results in a schedule that cannot be ordered and .

The SQL standard does not provide for the concept of locks to implement the serializability of a mixture of transactions. Instead, the concept of isolation levels is introduced. This approach provides the necessary requirements for isolation of transactions, leaving the possibility for manufacturers of various DBMS to implement these requirements in their own ways (in particular, using locks or extracting versions of data).

The SQL standard provides 4 levels of isolation:

If all transactions are executed at the ordering ability level (the default), then the alternating execution of any set of parallel transactions can be ordered. If some transactions are executed at lower levels, then there are many ways to disrupt the ordering ability. In the SQL standard, there are three special cases of violation of the ability to streamline, in fact, those that were described above as problems of parallelism:

The loss of the update results by the SQL standard is not allowed, i.e. at the lowest isolation level, transactions must operate in such a way as to prevent the loss of update results.

Различные уровни изоляции определяются по возможности или исключению этих особых случаев нарушения способности к упорядочению. Эти определения описываются следующей таблицей:

| Уровень изоляции | Неаккуратное считывание | Неповторяемое считывание | Фантомы |

|---|---|---|---|

| READ UNCOMMITTED | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| READ COMMITTED | Not | Yes | Yes |

| REPEATABLE READ | Not | Not | Yes |

| SERIALIZABLE | Not | Not | Not |

Таблица 4 Уровни изоляции стандарта SQL

Уровень изоляции транзакции задается следующим оператором:

SET TRANSACTION { ISOLATION LEVEL { READ UNCOMMITTED | READ COMMITTED | REPEATABLE READ | SERIALIZABLE } | { READ ONLY | READ WRITE }}.,..

Этот оператор определяет режим выполнения следующей транзакции, т.е. этот оператор не влияет на изменение режима той транзакции, в которой он подается. Обычно, выполнение оператора SET TRANSACTION выделяется как отдельная транзакция:

… (предыдущая транзакция выполняется со своим уровнем изоляции) COMMIT; SET TRANSACTION ISOLATION LEVEL REPEATABLE READ; COMMIT; … (следующая транзакция выполняется с уровнем изоляции REPEATABLE READ)

Если задано предложение ISOLATION LEVEL, то за ним должно следовать один из параметров, определяющих уровень изоляции.

Кроме того, можно задать признаки READ ONLY или READ WRITE. Если указан признак READ ONLY, то предполагается, что транзакция будет только читать данные. При попытке записи для такой транзакции будет сгенерирована ошибка. Признак READ ONLY введен для того, чтобы дать производителям СУБД возможность уменьшать количество блокировок путем использования других методов сериализации (например, метод выделения версий).

Оператор SET TRANSACTION должен удовлетворять следующим условиям:

Современные многопользовательские системы допускают одновременную работу большого числа пользователей. При этом если не предпринимать специальных мер, транзакции будут мешать друг другу. Этот эффект известен как проблемы параллелизма.

Имеются три основные проблемы параллелизма:

График запуска набора транзакций называется последовательным , если транзакции выполняются строго по очереди. Если график запуска набора транзакций содержит чередующиеся элементарные операции транзакций, то такой график называется чередующимся . Два графика называются эквивалентными , если при их выполнении будет получен один и тот же результат, независимо от начального состояния базы данных . График запуска транзакции называется верным ( сериализуемым ), если он эквивалентен какому-либо последовательному графику.

Решение проблем параллелизма состоит в нахождении такой стратегии запуска транзакций, чтобы обеспечить сериализуемость графика запуска и не слишком уменьшить степень параллельности.

Одним из методов обеспечения сериальности графика запуска является протокол доступа к данным при помощи блокировок. В простейшем случае различают S-блокировки (разделяемые) и X-блокировки (монопольные). Протокол доступа к данным имеет вид:

Если все транзакции в смеси подчиняются протоколу доступа к данным, то проблемы параллелизма решаются (почти все, кроме "фантомов"), но появляются тупики. Состояние тупика ( dead locks ) характеризуется тем, что две или более транзакции пытаются заблокировать одни и те же объекты, и бесконечно долго ожидают друг друга.

Для разрушения тупиков система периодически или постоянно поддерживает графа ожидания транзакций. Наличие циклов в графе ожидания свидетельствует о возникновении тупика. Для разрушения тупика одна из транзакций (наиболее дешевая с точки зрения системы) выбирается в качестве жертвы и откатывается.

Для решения проблемы "фантомов", а также для уменьшения накладных расходов, вызываемых большим количеством блокировок, применяются более сложные методы. Одним из таких методов являются преднамеренные блокировки , блокирующие объекты разной величины - строки, страницы, таблицы, файлы и др.

Альтернативным является метод предикатных блокировок

Имеются также методы сериализации, не использующие блокировки. Это метод временных меток и механизм выделения версий . Механизм выделения версий удобен тем, что он позволяет одновременно, и читать, и изменять одни и те же данные разными транзакциями. Это увеличивает степень параллельности, и общую производительность системы.

Стандарт SQL не предусматривает понятие блокировок. Вместо этого вводится понятие уровней изоляции . Стандарт предусматривает 4 уровня изоляции:

Transactions can run with different levels of isolation.

Comments

To leave a comment

Databases, knowledge and data warehousing. Big data, DBMS and SQL and noSQL

Terms: Databases, knowledge and data warehousing. Big data, DBMS and SQL and noSQL