Lecture

The main consequences of inflation are: 1) a decline in real incomes and 2) a decrease in the purchasing power of money.

• Revenues distinguish between nominal and real. Nominal income is the amount of money a person receives for the sale of an economic resource that owns it. Real income is the amount of goods and services that a person can buy for his nominal income (for the amount of money received).

real income = nominal income / price level = nominal income / (1 + π),

where π is the inflation rate.

The higher the level of prices for goods and services (i.e., the higher the rate of inflation), the smaller the amount of goods and services people can buy for their nominal incomes, so the lower the real incomes. In this regard, hyperinflation has a particularly unpleasant effect, which leads not only to a fall in real incomes, but to a destruction of wealth.

• The purchasing power of money is the quantity of goods and services that can be bought for one monetary unit. If the price level rises, the purchasing power of money falls. If P is the price level, i.e. the value of goods and services, expressed in money, the purchasing power of money will be equal to 1 / P, i.e. it is the value of money expressed in goods and services for which money can be exchanged.

For example, if a basket of goods and services costs $ 5, then P = $ 5. The price of the dollar will then be 1 / P or 1/5 of the basket of goods. This means that one dollar is exchanged for 1/5 of a basket of goods. If the price of the basket of goods doubles so that it now costs $ 10, the price of money falls by half its original value. Since the basket price is now equal to $ 10 or P = $ 10, the price of money has dropped to 1 / P or 1/10 of the basket of goods. Thus, when the price of the basket of goods and services doubles from $ 5 to $ 10, the price of money drops from 1/5 to 1/10 of the basket of goods.

The higher the price level, i.e. the higher the rate of inflation, the lower the purchasing power of money, and, consequently, the less people want to have less money, because those people who keep cash during the inflation period pay a kind of inflation tax - a tax on the purchasing power of money, which is the difference between values of the purchasing power of money at the beginning and at the end of the period during which inflation occurred. The more cash a person has and the higher the rate of inflation, the greater the value of the inflation tax, since the greater the purchasing power (value) of money. Therefore, in periods of high inflation and especially hyperinflation, a process called “run from money” occurs. Real values are becoming increasingly important, not money. In his book The United States Monetary History, Milton Friedman, analyzing hyperinflation in Germany in October 1923, wittily described the difference between inflation and hyperinflation as follows: if a person who carries a cart loaded with bags of money leaves it at the store entrance, and from the store, finds that the cart is in place, and the bags of money have disappeared - then this is inflation; and if he sees that the cart has disappeared and the money bags are intact, then this is hyperinflation.

Inflation has serious costs. These include:

• the cost of “worn shoes” (shoeleather costs). These are the so-called transaction costs of inflation, i.e. costs associated with obtaining cash. Since inflation entails a tax on cash, then, trying to avoid this tax, people try to keep less cash on hand and either invest it in a bank or buy securities that generate income. If a person’s income is transferred to his bank account, then as the price level rises, a person must withdraw to the bank more often, spend money on travel or stomp shoes, going there on foot, spend time standing in a queue, and so on, to withdraw money from the account. P. If a person invests in securities - stocks or bonds, then he must sell them in order to receive cash, i.e. spend time, find a broker (securities market broker), pay him a commission, and therefore, in this case, he is faced with transaction costs.

• menu costs. This kind of costs are borne by the selling companies. When prices change, they should a) frequently change price lists, price lists, reprint catalogs of their products, which requires considerable printing costs, b) incur postal costs of distributing them and advertising new prices, c) incurring the costs of making decisions about the new prices themselves.

• costs at the microeconomic level associated with changes in relative prices and reduced efficiency as a result of deteriorating resource allocation (relative-price variability and the misallocation of resources). Since price changes are expensive (high menu costs), firms try to change prices as little as possible. In terms of inflation, the relative prices of those goods for which firms keep prices unchanged for a certain period of time also fall in relation to the prices of those goods for which firms quickly change prices and in relation to the average price level. This worsens the allocation of resources, since economic decisions are based on relative prices, i.e. resources are directed to those types of industries that produce more expensive goods. Meanwhile, the change in relative prices in the period of inflation does not reflect the real difference in the efficiency of production of different types of goods, but only the difference in the rate of change in prices for goods by different firms. A product whose price changes only once a year is artificially high at the beginning of the year and artificially low at the end of the year.

• costs of tax distortions caused by inflation (inflation-induced tax distortions). Inflation increases the tax burden on income earned on savings, and thus reduces savings incentives, and therefore worsens conditions and opportunities for economic growth.

Inflation affects two types of income on savings:

- on proceeds from the sale of securities (capptal gains), which represent the difference between the higher price at which the security is sold and the lower price at which it was bought. This nominal income is subject to taxation. Suppose a person buys a bond for $ 20 and sells it for $ 50. If during the time he owned a bond, the price level doubled, then his real income will be not $ 30 ($ 50 - $ 20), but only $ 10, since he will have to sell the bond for $ 40 to only refund its value paid at purchase. and pay tax not from $ 10 ($ 50 - $ 40), but from $ 30 of nominal income, because the tax code does not take into account inflation.

- the nominal interest rate that is taxed, even though a part of the nominal interest rate in accordance with the Fisher effect (which will be discussed in the next paragraph) simply compensates for inflation. When the government takes as a tax a fixed percentage of the nominal interest rate, the real income remaining after the tax is paid increases the lower the higher the rate of inflation. This happens because the nominal interest rate increases by the same amount as the inflation rate, and with an increase in the nominal interest rate, taxes increase, so inflation has no effect on real income before tax payment. However, real income after tax is reduced.

Since a tax is levied on nominal income from the sale of securities and a nominal interest rate, inflation reduces real income from savings after the tax has been paid, and thus inflation reduces incentives for savings and reduces opportunities for economic growth.

• costs associated with the fact that money ceases to perform its functions, which causes confusion and inconvenience. Money serves as a unit of account, by which the value of all goods and services is measured. Just as the distance is measured in meters, weight is in kilograms, and temperature is in degrees, cost is measured in monetary units (rubles, dollars, pounds sterling, etc.).

When the central bank increases the money supply, which provokes inflation, the value (purchasing power) of money falls, i.e. the size of the “economic measuring stick” decreases. For example, for 1 depreciated ruble you can buy as many goods as earlier by 50 kopecks, i.e. the meter has halved, equivalent to as if we were trying to measure the distance with a ruler that says 1 meter, but in reality it is only 50 cm. On the one hand, it makes transactions (transactions) more confusing, but on the other hand, makes it difficult to calculate the profits of firms and, thus, makes the choice in favor of investment more problematic and difficult.

All these costs exist even if inflation is stable and predictable. Inflation, however, has an additional cost for the economy if it is a special cost of unexpected inflation.

The effects of inflation vary depending on whether it is expected (expected) or unexpected.

Under the conditions of expected inflation, economic agents can thus build their behavior in order to minimize the magnitude of the fall in real incomes and the depreciation of money. Thus, workers may demand an increase in the nominal wage rate in advance, and firms may provide for an increase in prices for their products in proportion to the expected rate of inflation. Lenders will provide loans at a nominal interest rate (R) equal to the sum of the real interest rate (real loan yield) - r and the expected inflation rate - π e :

R = r + π e

Since the loan is provided at the beginning of the period, and is paid by the borrower at the end of the period, it is the expected rate of inflation that matters.

This dependence of the nominal interest rate on the expected rate of inflation is called the “Fisher effect” (in honor of the well-known American economist Irving Fisher, who first substantiated this dependence). The “Fisher effect” is formulated as follows: if the expected inflation rate rises by 1 percentage point, the nominal interest rate will also increase by 1 percentage point. From here you can get a formula for calculating the real interest rate: r = R - π e .

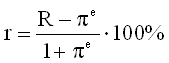

However, it should be borne in mind that this formula is valid only for low rates of inflation (up to 10%), and for high rates of inflation it is necessary to use another formula:

This is because it is necessary not only to calculate the amount of income (real interest rate), but also to evaluate its purchasing power. And since the price level changes by an amount equal to? E, the income value equal to the difference between the nominal interest rate and the expected inflation rate should be divided into a new price level, i.e. (1 + π e ). At low rates of inflation, this amount will be close to 1, but at high rates of inflation, it becomes a significant value that cannot be neglected.

The consequence of unanticipated inflation is an arbitrary redistribution of income and wealth (arbitrary redistribution of wealth). It enriches some economic agents and impoverishes others. Income and wealth move:

• from creditors to debtors. The lender provides a loan at a nominal interest rate, based on the amount of real income that he wants to receive (real interest rate) and the expected rate of inflation (R = r +? E). So, for example, wanting to get a real income of 5% and assuming that the inflation rate will be 10%, the lender will appoint a nominal interest rate of 15% (5% + 10%). If the actual inflation rate is 15% instead of the expected 10%, the creditor will not receive any real income (r = 15 - 15 = 0), and if the inflation rate is 18%, then the income equal to 3% (r = 15 - 18 = - 3) move from creditor to debtor. Therefore, in periods of unexpected inflation it is very profitable to take loans and it is unprofitable to give them.

Thus, unanticipated inflation works as a tax on future receipts and as a subsidy for future payments. Therefore, if it turns out that inflation is higher than expected at the time of signing the loan contract, the recipient of future payments (the lender) is worse because he will receive money with a lower purchasing power than those that he agreed upon when signing the contract. The person who borrowed money (the borrower) is better because he had the opportunity to use the money when they had a higher cost, and he was allowed to repay the debt with lower cost money. When inflation is higher than expected, wealth is redistributed from lenders to borrowers. When inflation is lower than expected, winners and losers switch places.

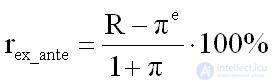

Since, as already noted, the general formula of the real interest rate, applicable at any rate of inflation:

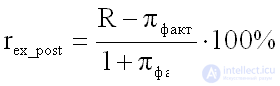

This should distinguish the real ex ante interest rate and the real ex post interest rate. The above formula is the ex ante real interest rate formula. The real interest rate ex ante is the real income that the lender expects to receive by providing a loan, so it is determined by the value of the expected rate of inflation (π e ). The real ex post rate is the real income that the lender receives when repaying the loan, so it is determined by the actual rate of inflation (π fact) and can be calculated using the formula:

• from workers to firms. The claim that unanticipated inflation works as a tax on future receipts and as a subsidy on future payments is applied to any contract that lasts over time, including a labor contract. When inflation is higher than expected, those who receive money in the future (workers) are detrimental, and those who pay (firms) win. Therefore, firms benefit from workers when inflation is higher than expected. When inflation is less than expected, the winners and losers change places.

• from people with fixed incomes to people with non-fixed incomes People with fixed incomes (for example, government employees, as well as people living on transfer payments) cannot take measures to increase their nominal incomes and during periods of unanticipated inflation (if indexation is not carried out income) their real incomes are falling rapidly. People with non-fixed income have the opportunity to increase their nominal income in accordance with the rate of inflation, so their real income may not decrease or even increase.

• from people who have savings in cash, to people who do not have savings. The real value of savings as inflation rises decreases, so the real wealth of those who have it in cash decreases.

• from the elderly to the young. The elderly suffer from unanticipated inflation to the greatest extent, since, on the one hand, they receive fixed incomes, and, on the other hand, they, as a rule, have savings in cash. Young people, having the opportunity to increase their nominal incomes and not having cash savings, suffer the least.

• from all economic agents with cash to the state. Unforeseen inflation affects the entire population to a certain extent.

But only one economic agent is always enriched - the state. By issuing additional money into circulation (by issuing money), the state thus establishes, as already noted, a kind of tax on cash, which is called seignorage. The state buys goods and services, and pays with depreciating money, i.e. money, the purchasing power of which is lower, the more extra money is released into circulation. The difference between the purchasing power of money before the emission and after it is the government’s income from inflation — seignorage.

The most serious and devastating effects are caused by hyperinflation, which results in:

Comments

To leave a comment

Macroeconomics

Terms: Macroeconomics