Lecture

Banks are the main financial intermediary in the economy. Banking activity is the channel through which changes in the money market are transformed into changes in the commodity market.

Banks are financial intermediaries because, on the one hand, they accept deposits, attracting depositors' money, i.e. accumulate temporarily free funds, and on the other hand, provide them at a certain percentage to various economic agents (firms, households, etc.), i.e. give loans. Thus, banks are intermediaries in credit. Therefore, the banking system is part of the credit system. The credit system consists of banking and non-bank (specialized) credit institutions. Non-bank credit institutions include: funds (investment, pension, etc.); companies (insurance, investment); financial companies (savings and loan associations, credit unions); pawn shops, i.e. all organizations acting as credit intermediaries.

However, the main financial intermediaries are commercial banks. The word "bank" comes from the Italian word "banco", which means "bench (money changers)." The first banks with the modern accounting principle of double entry appeared in the sixteenth century in Italy, although usury (i.e. lending money) as the first form of credit flourished before BC. The first special credit institutions appeared in the Ancient East in the 7th-6th centuries BC, the credit functions of banks in ancient Greece and ancient Rome were performed by churches, and in medieval Europe — monasteries.

Modern two-tier banking system. The first level is the Central Bank. The second level is the system of commercial banks.

The central bank is the main bank in the country. In the USA, it is called the Fed (Federal Reserve System - Federal Reserve System), in Great Britain it is the Bank of England (Bank of England), in Germany - Bundesdeutchebank, in Russia - Central Bank of Russia, etc.

The central bank performs the following functions, being:

• the issuing center of the country (it has the monopoly right to issue banknotes, which provides it with constant liquidity. The money of the Central Bank consists of cash (banknotes and coins) and non-cash money (accounts of commercial banks at the Central Bank)

• a government banker (serves the government’s financial operations, mediates in treasury payments and government lending. The treasury stores free cash resources at the Central Bank in the form of deposits, and, in turn, the Central Bank gives all its profits above a certain predetermined rate. )

• banks of banks (commercial banks are central bank clients that keep their compulsory reserves, which allows them to control and coordinate their domestic and foreign activities, acts as a lender of last resort for commercial banks having difficulty, providing them with credit support by issuing money or selling securities)

• Interbank Clearing Center

• the custodian of the country's foreign exchange reserves (serves the country's international financial operations and controls the state of the balance of payments, acts as a buyer and seller in international currency markets).

• The central bank determines and implements monetary policy.

The second level of the banking system consists of commercial banks. There are: 1) universal commercial banks and 2) specialized commercial banks. Banks can specialize: 1) by objectives: investment (lending investment projects), innovative (issuing loans for the development of scientific and technological progress), mortgage (providing loans secured by real estate); 2) by industry: construction, agricultural, foreign trade; 3) by clients: servicing only firms, serving only the population, etc.

Commercial banks are private organizations that have the legal right to raise free cash and issue loans for profit. Therefore, commercial banks perform two main types of operations: passive (in attracting deposits) and active (in issuing loans). In addition, commercial banks perform: cash operations; trust (trust) operations; interbank transactions (credit - for issuing loans to each other and transfer - for transferring money); securities transactions; foreign exchange transactions, etc.

The main part of the income of a commercial bank is the difference between interest on loans and interest on deposits (deposits). Additional sources of income for the bank can be commissions for the provision of various types of services (trust, transfer, etc.) and income from securities. Part of the income goes to pay for bank expenses, which include salaries of bank employees, equipment costs, the use of computers, cash registers, room rent, etc. The amount remaining after these payments is the profit of the bank, dividends are paid to the shareholders of the bank and a certain part can be used to expand the bank’s activities.

Historically, banks mainly originated from jewelry shops. Jewelers had reliable secured basements for storing jewels, so over time people began to give them their valuables for storage, in return for jewelers' promissory notes confirming that they could get these values back on demand. This is how bank credit money came into being.

At first, the jewelry masters only kept the provided values and did not issue loans. This situation corresponds to the system of full or 100% reservation (the entire amount of deposits is stored as reserves). But gradually it turned out that all clients could not simultaneously demand the return of their deposits.

Thus, the bank is faced with a contradiction. If he keeps all his deposits in the form of reserves and does not issue loans, he loses his profits. But at the same time he ensures his 100% solvency and liquidity. If he gives out money to investors on credit, then he makes a profit, but there is a problem with solvency and liquidity. The solvency of a bank means that its assets should at least equal its debts. The bank’s assets include the notes they have and all the financial resources (bonds and debentures) that it buys from other persons or institutions. Bonds and debentures serve as a source of income for the bank. Bank debt (liabilities) - its liability is the amount of deposits placed in it, which it is obliged to return upon the first request of the client. If the bank wants to have a 100% solvency, then it should not lend anything from the funds placed in it. This eliminates the high risk, but the bank does not receive any profit in the form of interest on the loan amount and is unable to pay its costs. To exist, the bank must take risks and give loans. The greater the value of loans issued, the higher the profit and risk.

In addition to solvency, the bank must have another property - liquidity, i.e. the ability at any time to give any number of depositors a part of the deposit or the entire deposit in cash. If the bank keeps all deposits in the form of banknotes, it has absolute liquidity. But storing money, in contrast to, for example, bonds, gives no income. Therefore, the higher the liquidity of the bank, the lower its income. The bank must carefully weigh the costs of illiquidity (ie, loss of customer confidence) and the costs of not using available funds. The need to have more liquidity always reduces the income of the bank.

The main source of bank funds that can be provided on credit are demand deposits (funds on current accounts) and savings deposits. Bankers around the world have long understood that despite the need for liquidity, the bank’s daily liquidity funds should account for approximately 10% of the total amount of funds placed in it. According to probability theory, the number of customers wishing to withdraw money from an account is equal to the number of customers investing money. In modern conditions, banks operate in a partial reservation system, when a certain part of the deposit is stored as a reserve, and the remaining amount can be used to provide loans.

In the last century, the reservation rate, i.e. the share of deposits that could not be lent (the share of reserves in the total deposits - (R / D)) was determined empirically (by trial and error). In the nineteenth century, due to numerous bankruptcies, banks were tricky and cautious. The reserve ratio was set by the commercial banks themselves and was, as a rule, 20%. At the beginning of the twentieth century, due to the instability of the banking system, frequent banking crises and bankruptcies, the Central Bank took over the task of setting the required bank reserve rate (in the USA it happened in 1913), which gives it the ability to control the work of commercial banks.

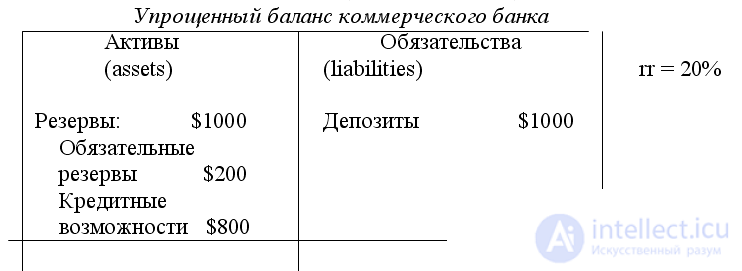

The required bank reserve ratio (or required reserve ratio - rr) is a percentage of the total deposits that commercial banks are not allowed to lend and expressed by the Central Bank in the form of interest-free deposits. In order to determine the amount of required reserves of the bank, you need to multiply the size of deposits (deposits - D) by the norm of reserve requirements: R on. = D x rr, where R about. - the value of required reserves, D - the amount of deposits, rr - the rate of reserve requirements. Obviously, with a full backup system, the reserve requirement rate is 1, and with a partial backup system, 0

If we subtract the amount of required reserves from the total amount of deposits, we get the amount of credit opportunities or excess reserves (over and above):

K = R g = D - R about. = D - D х rr = D (1 - rr)

where K is the credit capacity of the bank, and R g. - excess (in excess of required) reserves.

It is from these funds that the bank provides loans. If the bank’s reserves fall below the required amount of reserves (for example, in connection with depositors ’raids), the bank can take three options: 1) sell a portion of its financial assets (for example, bonds) and increase the amount of cash, losing interest income on bonds); 2) ask for help from the central bank, which lends money to banks to eliminate temporary difficulties at an interest rate, called the discount rate; 3) borrow from another bank in the interbank loan market; The interest paid is called the interbank interest rate (in the United States, the federal funds rate).

If a bank lends all of its excess reserves, this means that it uses its full credit facilities. In this case, K = R g. However, the bank may not do this, and retain part of the excess reserves without issuing a loan. The amount of required reserves and excess reserves, i.e. funds, not issued on credit (excess reserves), represents the actual reserves of the bank: R fact. = R about. + R excess

With a standard reserve requirement of 20%, with deposits in the amount of $ 1,000 (Fig. 12.3.), The bank must keep $ 200 (1000 x 0.2 = 200) in the form of required reserves, and the remaining $ 800 (1000 - 200 = 800) it can issue on credit. If he gives loans for all this amount, it means that he uses his credit opportunity completely. However, the bank may issue a loan only part of this amount, for example, $ 700. In this case, $ 100 (800 - 700 = 100) will make up its excess (excess) reserves. As a result, the actual reserves of the bank will be equal to $ 300 ($ 200 mandatory + $ 100 excess = $ 300)

Thanks to the partial reservation system, universal commercial banks can create money. It should be borne in mind that money can only be created by these credit institutions (neither non-bank credit institutions nor specialized banks can create money.

The process of creating money is called credit expansion or credit multiplication. It starts in the event that money enters the banking sector and deposits of a commercial bank increase, i.e. if cash becomes non-cash. If the value of deposits decreases, i.e. the client withdraws money from his account, then the opposite process will occur - credit squeeze.

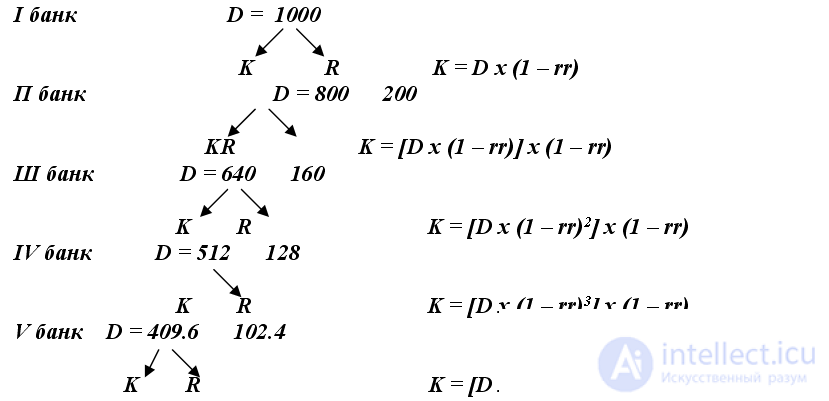

Suppose that I deposit a deposit of $ 1000, and the rate of reserve requirements is 20%. In this case, the bank must deduct $ 200 in required reserves (R oblig. = D x rr = 1000 x 0.2 = 200), and its credit capacity will be $ 800 (K = D x (1 - rr) = 1000 x (1 - 0.2) = 800). If he uses them completely, then his client (any economic agent, since the bank is universal) will receive a loan of $ 800. The client uses these funds for the purchase of goods and services he needs (the firm is investment, and the household is consumer or home purchase), creating an income (revenue) for the seller that gets a settlement account at another bank (for example, bank P) to his (seller) . Bank P, having received a deposit equal to $ 800, will transfer $ 160 (800 x 0.2 = 160) to the required reserves, and its credit capacity will amount to $ 640 (800 x (1 - 0.2) = 640), issuing which the bank will give a loan to its client transaction (purchase) for this amount, i.e. provide the seller with the proceeds, and $ 640 in the form of a deposit will go to the merchant's current account with Bank Sh. The required reserves of Bank Sh will be $ 128, and the credit opportunities are $ 512.

By providing a loan for this amount, Bank W creates a prerequisite for increasing the credit capacity of bank IV by $ 409.6, bank V by $ 327.68, etc. We get a kind of pyramid:

This is the process of deposit expansion. If the money will not leave the banking sector and settle with economic agents in the form of cash, and banks will fully use their credit facilities, then the total amount of money (total bank deposits I, P, III, IV, V, etc.) created by commercial banks will be:

M = DI + D P + D W + D IV + DV + ... =

= D + D x (1 - rr) + [D x (1 - rr)] x (1 - rr) + [D x (1 - rr) 2] x (1 –rr) +

+ [D x (1 - rr) 3] x (1 - rr) + [D x (1 - rr) 4] x (1 - rr) + ... =

= 1000 + 800 + 640 + 512 + 409.6 + 327.68 + ...

In this way. we obtained the sum of an infinitely decreasing geometric progression with a base (1 - rr), i.e. values less than 1. In general, this amount will be equal toM = D x 1 / (1 - (1 - rr)) = D x 1 / rr

In our case, M = 1000 x 1 / 0.8 = 1000 x 5 = 5000

The value 1 / rr is called the bank (or credit, or deposit) multiplier multbank = 1 / rr

Another name is the deposit expansion multiplier. All these terms mean the same thing, namely: if deposits of commercial banks increase, then the money supply increases to a greater degree. The bank multiplier shows how many times the magnitude of the money supply changes (increases or decreases) if the value of deposits of commercial banks changes (respectively, increases or decreases) by one unit. Thus, the multiplier acts in both directions. The money supply increases if money enters the banking system (the amount of deposits increases), and decreases if money leaves the banking system (i.e. it is withdrawn from deposits). And since, as a rule, in the economy, money is simultaneously invested in banks and withdrawn from accounts, the money supply cannot change significantly. Such a change can occur only if the Central Bank changes the rate of required reserves, which affects the credit capacity of banks and the value of the banking multiplier. It is not by chance that this is one of the important instruments of the monetary policy (the policy of regulating the money supply) of the Central Bank. (In the USA, the bank multiplier is 2.7).

With the help of the banking multiplier, it is possible to calculate not only the value of the money supply (M), but also its change (Δ M). Since the value of the money supply consists of cash and non-cash money (funds on current accounts of commercial banks), i.e. M = C + D, then the bank I deposit ($ 1000) came from the sphere of cash circulation, i.e. they already constituted a part of the money supply, and only a redistribution of funds between C and D occurred. Consequently, the money supply as a result of the deposit expansion process increased by $ 4000 (Δ М = 5000 - 1000 = 4000), i.e. Commercial banks have created money for this amount. This was the result of their lending their excess (in excess of required) reserves, so the process of increasing the money supply began with an increase in the total amount of deposits of the bank P as a result of a loan given by bank I to the amount of its excess reserves (credit opportunities) equal to $ 800. Consequently, the change in the money supply can be calculated by the formula:

Δ M = D P + D W + D IV + DV + ... =

= D x (1 - rr) + [D x (1 - rr)] x (1 - rr) + [D x (1 - rr) 2] x (1 –rr) +

+ [D x (1 - rr) 3] x (1 - rr) + [D x (1 - rr) 4] x (1 - rr) + ... =

= 800 + 640 + 512 + 409.6 + 327.68 + ... = 800 x (1 / 0.8) = 800 x 5 = 4000

or

Δ M = [D x (1 - rr)] x (1 / rr) = K x (1 / rr) = R g. x (1 / rr) = 800 x (1 / 0.8) = 4000

Thus, a change in the money supply depends on two factors:

Considering the process of deposit expansion, we assumed that: 1) the money does not leave the banking sector and does not settle in the form of cash, 2) credit opportunities are used by banks completely and 3) the money supply is determined only by the behavior of the banking sector. However, when studying the money supply, it should be borne in mind that its value is influenced by the behavior of households and firms (the non-banking sector), and it is also important to take into account the fact that commercial banks may not fully use their credit opportunities, while keeping excess reserves which they do not lend. And under such conditions, a change in the value of deposits has a multiplicative effect, but its value will be different. We derive the money multiplier formula:

Денежная масса (М1) состоит из средств на руках у населения (наличные деньги) и средств на текущих банковских счетах (депозиты): М = С + D

Однако центральный банк, который осуществляет контроль за предложением денег не может непосредственно воздействовать на величину предложения денег, поскольку не он определяет величину депозитов, а может только косвенным образом влиять на их величину через изменение нормы резервных требований. Центральный банк регулирует только величину наличности (поскольку он сам ее пускает в обращение) и величину резервов (поскольку они хранятся на его счетах). Сумма наличности и резервов, контролируемых центральным банком, носит название денежной базы (monetary base) или денег повышенной мощности (high-powered money) и обозначается (Н): Н = С + R

Каким образом центральный банк может контролировать и регулировать денежную массу? Это оказывается возможным через регулирование величины денежной базы, поскольку денежная масса представляет собой произведение величины денежной базы на величину денежного мультипликатора.

Чтобы вывести денежный мультипликатор, введем следующие понятия: 1) норма резервирования rr (reserve ratio), которая равна отношению величины резервов к величине депозитов: rr = R/D или доле депозитов, помещенных банками в резервы. Она определяется экономической политикой банков и регулирующими их деятельность законами; 2) норма депонирования сr (), которая равна отношению наличности к депозитам: сr = С/D. Она характеризует предпочтения населения в распределении денежных средств между наличными деньгами и банковскими депозитами.

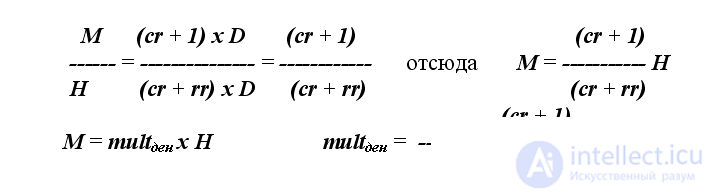

Since C = cr x D, and R = rr x D, we can write:

M = C + D = CR x D + D = (CR + 1) x D (1)

H = C + R = сr x D + rr x D = (cr + rr) x D (2)

Divide (1) by (2), we get:

The value [(cr + 1) / (cr + rr)] is the money multiplier or money base multiplier, i.e. a coefficient that shows how many times the money supply increases (decreases) with an increase (reduction) in the monetary base by one. Like any multiplier, it acts both ways. If the central bank wants to increase the money supply, it must increase the money base, and if it wants to reduce the money supply, then the money base should be reduced.

Заметим, что если предположить, что наличность отсутствует (С=0), и все деньги обращаются только в банковской системе, то из денежного мультипликатора мы получим банковский (депозитный) мультипликатор: multD = 1/ rr . Не случайно банковский мультипликатор часто называют «простым денежным мультипликатором» (simple money multiplier), а денежный мультипликатор - сложным денежным мультипликатором или просто денежным мультипликатором (money multiplier).

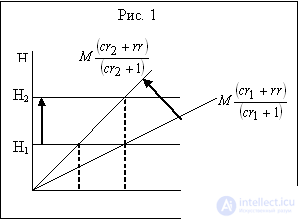

Величина денежного мультипликатора зависит от нормы резервирования и нормы депонирования. Чем они выше, т.е. чем больше доля резервов, которую банки не выдают в кредит и чем выше доля наличности, которую хранит население на руках, не вкладывая ее на банковские счета, тем величина мультипликатора меньше. Это можно показать на графике, на котором представлено соотношение денежной базы (Н) и денежной массы (М) через денежный мультипликатор, равный: (сr + 1)/(сr + rr) Очевидно, что тангенс угла наклона равен (cr + rr)/(cr + 1) (рис. 1.).

При неизменной величине денежной базы Н1 рост нормы депонирования от сr1 до сr2 сокращает величину денежного мультипликатора и увеличивает наклон кривой денежной массы (предложения денег), в результате предложение денег сокращается от М1 до М2. Чтобы при снижении величины мультипликатора денежная масса не изменилась (сохранилась на уровне М1, центральный банк должен увеличить денежную базу до Н2. Итак, рост нормы депонирования уменьшает величину мультипликатора. Аналогично можно показать, что рост нормы резервирования (увеличения банками доли депозитов, хранимых в виде резервов), т.е. чем больше величина избыточных, не выдаваемых в кредит, банковских резервов, тем меньше величина мультипликатора.

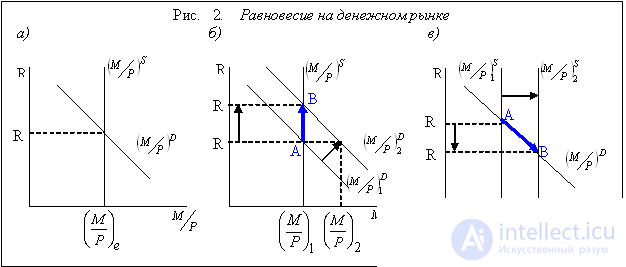

Равновесие денежного рынка устанавливается автоматически за счет изменения ставки процента. Денежный рынок очень эффективен и практически всегда находится в равновесии, поскольку на рынке ценных бумаг очень четко действуют дилеры, которые отслеживают изменения процентных ставок и заставляют их перемещаться в одном направлении.

Предложение денег контролирует центральный банк, поэтому можно изобразить кривую предложения денег как вертикальную, т.е. не зависящую от ставки процента (М/Р)S. Спрос на деньги отрицательно зависит от ставки процента, поэтому он может быть изображен кривой, имеющей отрицательный наклон (М/Р)D. Точка пересечения кривой спроса на деньги и предложения денег позволяет получить равновесную ставку процента R и равновесную величину денежной массы (М/Р) (рис. 2.(а)).

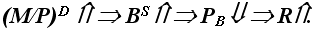

Рассмотрим последствия изменения равновесия на денежном рынке. Предположим, что величина предложения денег не меняется, но повышается спрос на деньги – кривая (М/Р)D1 сдвигается вправо-вверх до (М/Р)D2. В результате равновесная ставка процента повысится от R1 до R2 (рис. 2.(б)). Экономический механизм установления равновесия на денежном рынке объясняется с помощью кейнсианской теории предпочтения ликвидности. Если в условиях неизменной величины предложения денег спрос на наличные деньги увеличивается, люди, имеющие, как правило, порфтель финансовых активов, т.е. определенное сочетание денежных и неденежных финансовых активов (например, облигаций), испытывая нехватку наличных денег, начинают продавать облигации. Предложение облигаций на рынке облиигаций увеличивается и превышает спрос, поэтому цена облигаций падает, а цена облигации, как уже было доказано, находится в обратной зависимости со ставкой процента, следовательно, ставка процента растет. Этот механизм можно записать в виде логической цепочки:

Рост спроса на деньги привел к росту равновесной ставки процента, при этом предложение денег не изменилось и величина спроса на деньги вернулась к исходному уровню, поскольку при более высокой ставке процента (более высоких альтернативных издержках хранения наличных денег), люди будут сокращать свои запасы наличных денег, покупая облигации.

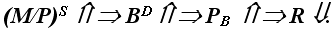

Рассмотрим теперь последствия изменения предложения денег для равновесия денежнорго рынка. Предположим, что центральный банк увеличил предложение денег, и кривая предложения денег сдвинулась вправо от (М/Р)S1 до (М/Р)S2 (рис. 2.(в)). Как видно из графика, результатом является восстановления равновесия денежного рынка за счет снижения ставки процента от R1 до R2. Объясним экономический механизм этого процесса, опять используя кейнсианскую теорию предпочтения ликвидности. При росте предложения денег у людей увеличивается количество наличных денег на руках, однако часть этих денег будет относительно излишней (ненужной для покупки товаров и услуг) и будет израсходована для покупки приносящих доход ценных бумаг (например, облигаций). На рынке облигаций повысится спрос на облигации, поскольку все их захотят купить. Рост спроса на облигации в условиях их неизменного предложения приведет к росту цены облигаций. А поскольку цена облигации находится в обратной зависимости со ставкой процента, то ставка процента упадет. Запишем логическую цепочку:

Итак, рост предложения денег ведет к снижению ставки процента. Низкая ставка процента означает, что альтернативные издержки хранения наличных денег низкие, поэтому люди будут увеличивать количество наличных денег, и величина спроса на деньги увеличится от (М/Р) 1 до (М/Р) 2 (движение из точки А в точку В вдоль кривой спроса на деньги (М/Р) D ).

Таким образом, теория предпочтения ликвидности исходит из обратной зависимости между ценой облигации и ставкой процента и объясняет равновесие денежного рынка следующим образом: изменение спроса на деньги или предложения денег соответствующие изменения в предложении и спросе на облигации, что вызывает изменение в ценах на облигации и через них – в ставках процента. Изменение в ставках процента (меняющее величину альтернативных издержек хранения наличных денег) влияет на желание людей хранить наличные деньги (предпочитая их ликвидность), а изменение в желании людей хранить наличные деньги восстанавливает равновесие на денежном рынке, равновесная ставка процента выравнивает количество предлагаемых и требуемых наличных денег.

Comments

To leave a comment

Macroeconomics

Terms: Macroeconomics