Lecture

The foundations of the classical model were laid back in the 18th century, and its position was developed by such eminent economists as A. Smith, D. Ricardo, J.-B.Say, J.-S.Mill, A.Marshall, A.Pigou, and others.

The main provisions of the classical model are as follows:

Absolute price flexibility and mutual equilibration of markets is observed only in the long run. Consider how the markets interact in the classical model.

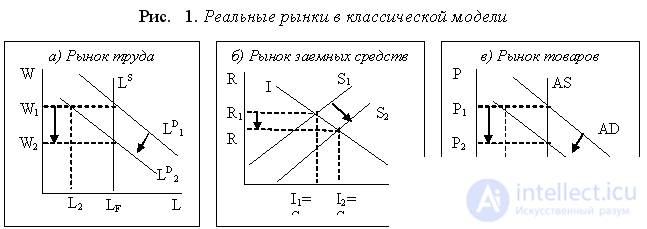

There are three real markets in the classical model: the labor market, the borrowed funds market and the commodity market (Fig. 1.)

Consider the labor market (Fig. 1. (a)). Since in the conditions of perfect competition resources are used completely (at the level of full employment), the labor supply curve (LS - labor supply curve) is vertical, and the volume of labor offered is equal to LF (full employment). The demand for labor depends on the wage rate, and the dependence is inverse (the higher the nominal wage rate (W - wage rate), the higher the costs of firms, and the smaller the number of workers they hire). Therefore, the labor demand curve (LD - labor demand curve) has a negative slope.

Initially, the equilibrium is established at the intersection of the labor supply curve (LS) and the labor demand curve (LD1) and corresponds to the equilibrium rate of nominal wages W1 and the number of employed LF. Suppose that the demand for labor has decreased, and the demand curve for labor LD1 has shifted to the left to LD2. At a nominal wage rate of W1, entrepreneurs will hire (demand for) a number of workers equal to L2. The difference between LF and L2 is none other than unemployment. Since there were no unemployment benefits in the 19th century, then, according to representatives of the classical school, workers, as rationally operating economic agents, would prefer to receive a lower income than not receive any. The nominal wage rate will drop to W2, and the full employment of LF will again be restored in the labor market. Unemployment in the classical model is therefore voluntary, since it is caused by the worker’s refusal to work for this nominal wage rate (W2). Thus, workers voluntarily doom themselves to unemployment.

The borrowed funds market (Fig. 1. (b)) is the market in which investments (I – investment) and savings (S – savings) “meet” and the equilibrium interest rate (R - interest rate) is established. The demand for borrowed funds is made by firms using them to buy investment goods, and the supply of credit resources is carried out by households by lending their savings. Investments negatively depend on the interest rate, since the higher the price of borrowed funds, the smaller the investment costs of firms, the investment curve therefore has a negative slope. The dependence of savings on the interest rate is positive, since the higher the interest rate, the greater the income that households receive from lending their savings. Initially, the equilibrium (investment = savings, i.e. I1 = S1) is established with the interest rate R1. But if savings increase (savings curve S1 shifts to the right to S2), then at the previous interest rate R1, part of savings will not generate income, which is impossible provided that all economic agents behave rationally. Savers (households) will prefer to receive income on all their savings, even at a lower interest rate. The new equilibrium interest rate will be established at the R2 level, at which all loan funds will be fully used, since at this lower interest rate, investors will take more loans and the investment will increase to I2, i.e. I2 = S2. The balance is established, and at the level of full employment of resources.

In the commodity market (Fig. 1. (c)), the initial equilibrium is established at the point of intersection of the aggregate supply curve AS and aggregate demand AD1, which corresponds to the equilibrium price level P1 and the equilibrium production at the level of potential output - Y *. Since all markets are connected with each other, a decrease in the nominal wage rate in the labor market (which leads to a decrease in income), and an increase in savings in the capital market cause a decrease in consumer spending, and, consequently, aggregate demand. The AD1 curve shifts to the left to AD2. At the same price level of P1, firms cannot sell all the products, but only a part equal to Y2. However, since firms are rational economic agents, they, under conditions of perfect competition, will prefer to sell all the produced output, even at lower prices. As a result, the price level will drop to P2, and the entire volume of production will be sold, i.e. equilibrium will again be established at the level of potential output (Y *)

The markets are self-balanced due to price flexibility, while the equilibrium in each of the markets is established at the level of full employment of resources. Only the nominal indicators changed, but the real ones remained unchanged. Thus, in the classical model, nominal indicators are flexible, and real indicators are rigid. This also applies to the real output (still equal to the potential output) and the real incomes of each economic agent. The fact is that prices in all markets change in proportion to each other, therefore the ratio W1 / P1 = W2 / P2, and the ratio of nominal wages to the general price level is nothing other than real wages. Consequently, despite the fall in nominal income, real income in the labor market remains unchanged.

Real incomes of savers (real interest rate) also did not change, since the nominal interest rate decreased in the same proportion as prices. The real incomes of entrepreneurs (sales revenues and profits) did not decrease, despite the fall in the price level, as the costs decreased to the same extent (labor costs, that is, the nominal wage rate). At the same time, the fall in aggregate demand will not lead to a drop in production, as a decline in consumer demand (as a result of a fall in nominal incomes on the labor market and an increase in savings on the capital market) will be offset by an increase in investment demand (as a result of a fall in interest rates on the capital market). Thus, the equilibrium was established not only in each of the markets, but there was also a mutual balancing of all markets with each other, and, consequently, in the economy as a whole.

From the provisions of the classical model it followed that protracted crises in the economy are impossible, and only temporary imbalances can occur, which are gradually eliminated by themselves as a result of the market mechanism - through the mechanism of price changes.

But at the end of 1929, a crisis broke out in the United States that swept the leading countries of the world, which lasted until 1933 and was called the Great Crash or the Great Depression. This crisis was not just another economic crisis. This crisis has shown the inconsistency of the provisions and conclusions of the classical macroeconomic model, and above all the idea of a self-regulating economic system. First, the Great Depression, which lasted four long years, could not be interpreted as a temporary disproportion, as a temporary failure of the mechanism of automatic market self-regulation. Secondly, what limited resources, as a central economic problem, could be discussed under conditions when, for example, in the USA the unemployment rate was 25%, i.e. one out of every four was unemployed (a person who wanted to work and was looking for work, but could not find it).

The causes of the Great Collapse, possible ways out of it, and recommendations to prevent similar economic catastrophes in the future were analyzed and substantiated in the book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, published in 1936. The result of the publication of this book was that macroeconomics was separated into a separate section of economic theory with its own subject and methods of analysis. Keynes’s contribution to economic theory was so great that the emergence of the Keynesian macroeconomic model, the Keynesian approach to the analysis of economic processes, was called the “Keynesian revolution”.

But it should be borne in mind that the inconsistency of the provisions of the classical school is not that its representatives, in principle, came to the wrong conclusions, but that the main provisions of the classical model were developed in the 19th century and reflected the economic situation of the time, i.e. era of perfect competition. But these provisions and conclusions did not correspond to the economy of the first third of the twentieth century, a characteristic feature of which was imperfect competition. Keynes denied the basic premises and conclusions of the classical school, building his own macroeconomic model.

Comments

To leave a comment

Macroeconomics

Terms: Macroeconomics