Lecture

Monetary and fiscal policies can be used to increase aggregate demand in the short run. The main difference between these two policies is the impact on the interest rate. Fiscal policy increases the interest rate, which leads to crowding out, while monetary policy reduces the interest rate if the economy is not in a liquid trap. These mechanisms are present in monetary and fiscal expansion and in an open economy, although there are important additional restrictions.

First, in the presence of capital flows, a change in the internal interest rate will have an impact on the capital account in the balance of payments. Under these conditions, it may not be possible to keep the internal interest rate at a level that is significantly different from the interest rate in other countries. Second, by influencing exchange rates, capital flows affect domestic demand, because the real exchange rate is an important factor in domestic demand, affecting exports and investments. This effect is absent at fixed exchange rates. But in this case, the consequences of a change in the interest rate on the money supply should be considered, since central bank interventions to maintain a certain exchange rate make the money supply endogenous (not controlled by the central bank) and not exogenous (fixed by the central bank), as previously assumed.

We will look at monetary and fiscal policies under fixed exchange rate and flexible exchange rate regimes. For our analysis, we assume that capital has perfect mobility throughout the world. This means that the internal interest rate cannot deviate from the global interest rate (that is, there is no exchange control and, therefore, domestic and foreign assets are perfect substitutes, and therefore should bring the same income). Obviously, such a premise is made only for analytical purposes. If there is no perfect mobility of capital, the results will be somewhat different, but the general conclusions will be maintained as long as there is at least some degree of capital mobility. In the beginning, we also assumed price fixing in order to study the effects on real aggregate demand. To analyze the effects of fiscal and monetary policy with fixed and floating exchange rates, we use a variant of the IS-LM model, known as the Mandell-Fleming model (after the two American economists who developed it).

To maintain fixed exchange rates, the central bank must intervene in the foreign exchange market from time to time. When there is an oversupply, such as pounds, the central bank of England will buy pounds and sell foreign currency to prevent the pound from falling. The supply of pounds in circulation will fall and foreign exchange reserves will decline. The money supply will decrease. Conversely, when the central bank sells pounds to stop the appreciation (appreciation) of the currency, the money supply will increase. If, for example, there is a “surplus” of the balance of payments, foreign currency flows into the central bank, which in return will offer pounds. Therefore, the money supply is the number of pounds in circulation in the domestic economy (known as domestic credit) plus reserves. Large reserves will increase the money supply. It is in this sense that the money supply is said to be endogenous. The authorities cannot simultaneously fix both the money supply and the exchange rate.

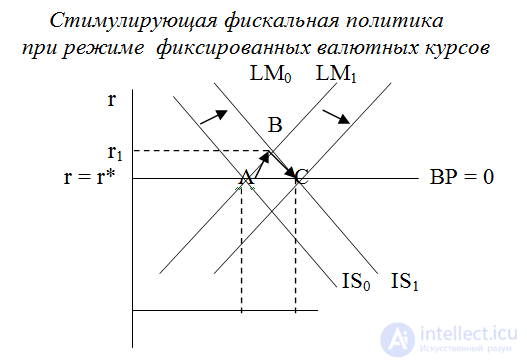

Fiscal policy. In fig. 1, the initial equilibrium is at the intersection of the IS0 and LM0 curves at point A. The horizontal line BP = 0 indicates external equilibrium. This means that the balance of payments is in balance (equal to zero). With perfect capital mobility, domestic and foreign interest rates should be equal (r = r *), otherwise net capital flows will occur. Therefore, any point that is not on the BP = 0 curve cannot correspond to the situation when the balance of payments is in equilibrium, since r is not equal to r *.

The growth in government spending financed by loans will shift the AC curve from IS0 to IS1, as aggregate demand in the domestic economy has increased as a result of a larger budget deficit. The interest rate rises as a result of higher income, and the economy moves to point B. The internal interest rate rises to r1. This will entail capital inflows, since r1 is greater than r *. The demand for pounds will increase as foreigners try to buy more British financial assets. With this fixed exchange rate, the central bank must provide an additional amount of pounds and accept foreign currency. The impact is to increase the supply of English money and reduce the interest rate. In fig. 26.1 this is shown as the shift of the LM curve from LM0 to LM1. The economy will again be in equilibrium at point C.

What determines the amount of capital inflow and income growth from Y0 to Y1? Capital inflows will continue as long as the internal interest rate is higher than r *. But capital inflows themselves have a downward effect on the interest rate because they increase the supply of English money. When the interest rate is again r *, capital inflows cease. Since financial assets are perfect substitutes around the world, investors will be willing to keep their capital in the UK because they receive the same interest rate that they could receive in any other country in the world, i.e. they will not take back their capital when the English interest rate falls again to r *. The net effect is that income increases to Y1 at unchanged interest rates. In this case, fiscal expansion also means monetary expansion. In terms of the balance of payments, there will be a trade deficit and a capital account surplus, but since the equilibrium is again on line BP = 0, the balance of payments will again be balanced. Revenue growth is determined by the size of the fiscal expansion. But fiscal policy is super efficient in an open economy with fixed exchange rates.

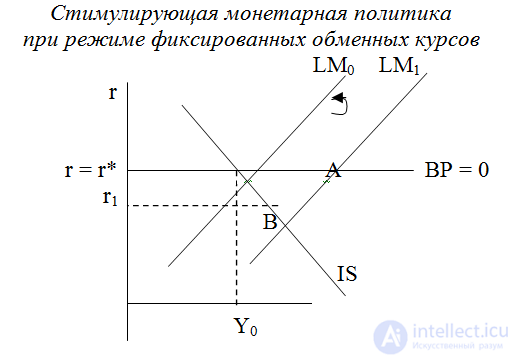

Monetary policy. The increase in the money supply shifts the LM curve from LM0 to LM1, which results in a decrease in the interest rate (point B in Fig. 2). This leads to capital outflows, since the internal interest rate is now lower than the global interest rate. The central bank must buy pounds and reduce its foreign exchange reserves in order to maintain a fixed exchange rate. This will reduce the money supply, since pounds bought by the central bank will no longer be in circulation in the domestic economy. The LM1 curve will shift back to LM0. Note that since the money supply is endogenous, the central bank cannot change the money supply independently of other countries under the fixed exchange rate regime.

There is no increase in output, since there is no increase in real aggregate demand. The actual growth in the supply of pounds is offset by capital outflows (loss of reserves), which increases the money supply and, as a consequence, the inflation rate in other countries. With fixed exchange rates, inflation is thus exported. More importantly, countries with fixed exchange rates lose their monetary independence. In other words, monetary policy is completely ineffective in an open economy with fixed exchange rates.

When exchange rates float freely, there is no need to have reserves, since the central bank does not attempt to intervene (intervene) in foreign exchange markets. The central bank has no obligation to provide foreign currency to people who want to buy foreign goods or foreign financial assets.

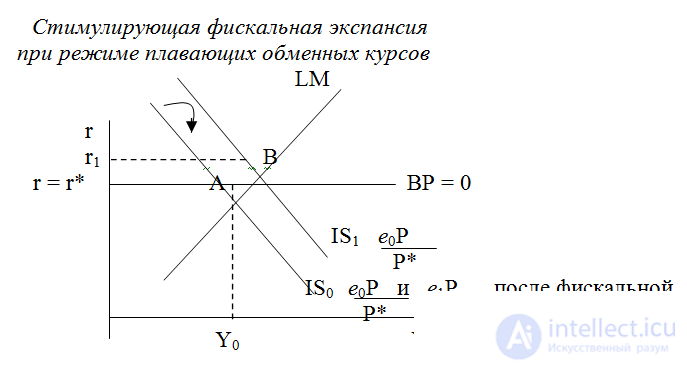

Fiscal policy. The increase in government spending financed with loans (so that the state budget deficit increases) shifts the IS curve from IS0 to IS1 in Figure 2. 3, raising the interest rate to r1. The resulting inflow of capital will lead to a rise in price (growth) of the exchange rate from e0 to e1. This increases the real exchange rate from e0 P / P * to e1 P / P *. The demand for internally produced goods will fall as imports become cheaper and exports are more expensive, i.e. there is a loss of competitiveness. The IS curve will shift to the left back to the original IS0 curve, as export demand falls. The reason why the economy moves back to the point of initial equilibrium is that as long as the internal interest rate is higher than the global interest rate, capital outflow will continue and the exchange rate will rise. This process can only stop when the internal interest rate is again equal to r *. The mechanism that reduces interest rates is a reduction in demand, especially export demand.

Thus, there is no change in output, and the net effect is only in the trade deficit, which is exactly equal to the size of the state budget deficit. The analysis performed means that fiscal policy is completely ineffective for increasing output when exchange rates float freely and capital is completely mobile. These conclusions are based on strict assumptions. In practice, domestic and foreign assets are not perfect substitutes and therefore there may be some deviation between domestic and foreign interest rates. In accordance with Fig. 3, this means that the line BP = 0 has a positive slope. Fiscal expansion in this case will not be completely ineffective.

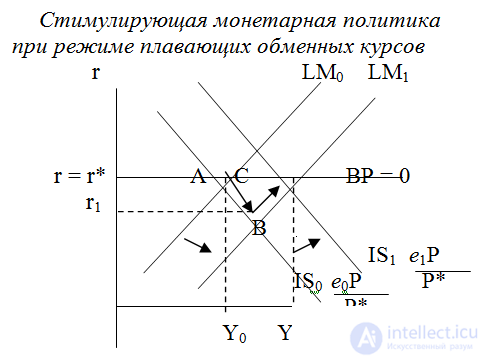

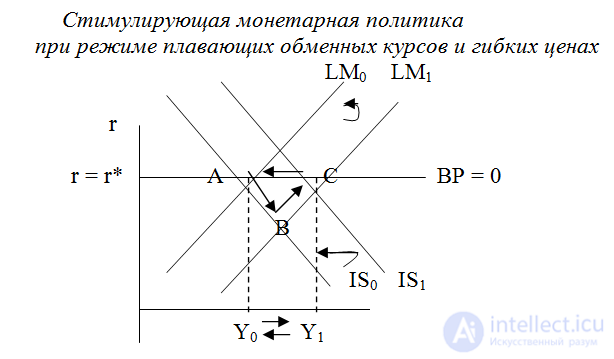

Monetary policy. In the case of monetary expansion (Fig. 4), the LM curve shifts to the right to LM0 to LM1, lowering the interest rate to r1 (ie, moving from A to B). In fact, this will increase the competitiveness, the resulting capital inflow leads to a depreciation of the currency from e0 to e1. The real exchange rate will fall, increasing the demand for domestic output, especially export demand. The IS curve shifts from IS0 to IS1, increasing the interest rate again to r * (i.e., the movement from m. B to m.C). As before, the system will return to equilibrium (BP = 0) through a change in the exchange rate, which will continue until r is less than r *. The net effect of monetary expansion is a capital account deficit and a trade surplus as a result of a decline in the real exchange rate. Higher output due to increased competitiveness. Monetary policy is super efficient in an open economy with floating exchange rates.

Floating exchange rates and flexible prices. Our analysis allowed us to determine which policy is effective for increasing aggregate demand under alternative exchange rate regimes. Increases in demand are fully consistent with output growth only when prices are fixed. When prices are not fixed, we must consider the effects of price increases, which may result from a surplus of expansionary government policies.

In fig. 5, we consider the case of monetary expansion with floating exchange rates. Initially, output increases to Y1, and the real exchange rate drops from e0 P0 / P * to e1 P0 / P * (since e1 <e0), as in fig. 4 (i.e., the economy moves from m. A to B and c. C). Suppose now that domestic prices have risen. There are two important channels through which output will be reduced:

1. The growth of domestic prices will increase relative prices and reduce competitiveness, i.e. will lead to an increase in the real exchange rate, which will lower the demand for internally produced goods and increase the demand for foreign goods. In accordance with Fig. 5, IS1 curve will shift back to IS0.

2. The price increase reduces the real money supply, which will shift the LM1 curve back to LM0, raising the interest rate. A higher interest rate will also increase the cost of currency.

Both of these effects act simultaneously. The IS curve shifts to the left, and the same happens with the LM curve. The economy is moving back to point A. The net effect is a higher price level, a lower nominal exchange rate (even though it is higher than at point C), but there are no long-term changes in the real exchange rate. This is explained by the fact that changes in e and P compensate each other, thus, e1 P1 / P * = e0 P0 / P * (while P1> P0, and e1 <e0). The nominal exchange rate first falls and then rises, but not to its initial level.

The speed at which the economy moves from m. A to m. B and c. C and back to m. A (especially the speed at which the economy moves from m. C to m. A) depends on the degree of price flexibility. If prices are very flexible, and therefore the market mechanism is very efficient, the movement back to tonnes will be very fast. State macroeconomic policies will be ineffective in moving the economy away from mA, with the exception of very short periods of time. This is the basis that monetarists and new classical economists believe in. Keynesians also believe that prices are sticky and adapt slowly. They believe that the movement between TS and TA is very slow. They therefore believe in the effectiveness of the macroeconomic policy of regulating aggregate demand in moving the economy from mA to t.C., since any tendency to move it back from m.C. to A.A will take many years. However, both monetarists and Keynesians recognize the importance of the policy of regulating aggregate supply, which helps move point A (the point that corresponds to production capabilities and full employment of resources) to the right.

Comments

To leave a comment

Macroeconomics

Terms: Macroeconomics