Lecture

The money market is a part (segment) of the financial market. The financial market is divided into the money market and the securities market. For a financial market to be in equilibrium, it is necessary that one of its markets be in equilibrium, then the other market will also automatically be in equilibrium. This follows from the Walras law, which states that if the economy has n markets, and (n - 1) market equilibrium, then there will be equilibrium in the nth market. Another formulation of the Walras law: the sum of excess demand for parts of the markets should be equal to the sum of excess supply in other markets. The application of this law for a financial market consisting of two markets allows us to limit our analysis to the study of equilibrium in only one of these markets, namely, the money market, since the equilibrium in the money market will provide an automatic balance in the securities market. We prove the validity of the Walras law for the financial market.

Each person (as a rational economic agent) forms a portfolio of financial assets, which includes both monetary and non-monetary financial assets. This is necessary because money has the property of absolute liquidity (the ability to quickly and without costs turn into any other assets, real or financial), but the money has zero yield. But non-monetary financial assets generate income (shares are dividends, and bonds are interest). To facilitate analysis, suppose that only bonds are sold on the stock market. Forming a portfolio of financial assets, a person is limited by budget constraints: W = M D + B D , where W is the nominal financial wealth of a person, M D is the demand for monetary financial assets in nominal terms and B D is the demand for non-monetary financial assets (bonds bonds) in nominal terms.

In order to eliminate the effect of inflation, it is necessary to use real, not nominal values in the analysis of the financial market. In order to get a budget constraint in real terms, all nominal values should be divided by the price level (P). Therefore, in real terms, the budget constraint takes the form:

Since we assume that all people act rationally, this budget constraint can be viewed as an aggregate budget constraint (at the level of the economy as a whole). And the real financial wealth of society (W / P), that is, the offer of all types of financial assets (monetary and non-monetary) is: W / P = (M / P) S + (B / P) S. Since the left sides of these equalities are equal, the right sides are equal: (M / P) D + (B / P) D = (M / P) S + (B / P) S, hence we get that: (M / P ) D - (M / P) S = (B / P) S - (B / P) S

Thus, the Walras law for the financial market is proven. Excess demand in the money market is equal to oversupply in the bond market. Therefore, we can limit our analysis to the study of equilibrium conditions only in the money market, which means automatic equilibrium in the bond market and, consequently, in the financial market as a whole.

Consider therefore the money market and the conditions of its equilibrium. As it is known, in order to understand the patterns of functioning of any market, it is necessary to investigate supply and demand, their relationship and the consequences (impact) of their changes on the equilibrium price and the equilibrium volume in this market.

The types of demand for money are due to two basic functions of money: 1) the function of the medium of circulation and 2) the function of the stock of value. The first function determines the first type of demand for money - transactional. Since money is a medium of circulation, i.e. act as an intermediary in the exchange, they are necessary for people to purchase goods and services, for making deals.

Transaction demand for money (transaction demand for money) is the demand for money for transactions (transactions), i.e. for the purchase of goods and services. This type of demand for money was explained in the classical model, was considered the only kind of demand for money, and was derived from the equation of the quantity theory of money, i.e. from the equation of exchange (proposed by the American economist I. Fisher) and the Cambridge equation (proposed by the English economist, professor at the University of Cambridge A. Marshall).

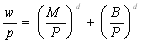

From the equation of the quantity theory of money (Fisher's equations): M x V = P x Y, it follows that the only factor in the real demand for money (M / P) is the value of real output (income) (Y). A similar conclusion follows from the Cambridge equation. By deriving this equation, A. Marshall suggested that if a person receives nominal income (Y), then he stores some share of this income (k) in the form of cash. For the economy as a whole, nominal income is equal to the product of real income (output) by the price level (P x Y), hence we get the formula: M = k PY, where M is the nominal demand for money, k is the liquidity ratio, showing what proportion of income is stored people in the form of cash, P - the price level in the economy, Y - the real output (income). This is the Cambridge equation, which also shows the proportional dependence of the demand for money on the level of total income (Y). Therefore, the formula for the transactional demand for money: (M / P) D T = (M / P) D (Y) = kY. (Note. From the Cambridge equation, you can get the exchange equation, since k = 1 / V).

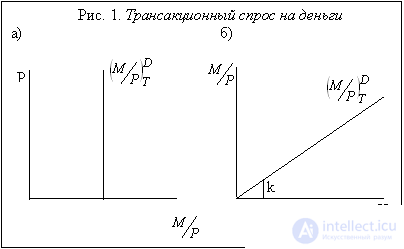

Since the transactional demand for money depends only on the income level (and this dependence is positive) (Fig. 1. (b)) and does not depend on the interest rate (Fig. 1. (a)), it can be graphically represented in two ways:

The view that the only motive for the demand for money is to use it to complete transactions existed until the mid-30s, until Keynes’s book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, came out in which Keynes referred to the transactional demand motive for money added another 2 motives for the demand for money - a motive of precaution and a speculative motive - and accordingly proposed another 2 types of demand for money: prudent and speculative.

The prudent demand for money (the demand for money from the precautionary motive - precautionary demand for money) is due to the fact that, in addition to the planned purchases, people also make unplanned ones. Anticipating such situations, when money may be needed unexpectedly, people store additional amounts of money in excess of what they need for planned purchases. Thus, the demand for money from the motive of caution also results from the function of money as a medium of circulation. According to Keynes, this type of demand for money does not depend on the interest rate and is determined only by the level of income, so its schedule is similar to the schedule of transactional demand for money.

Speculative demand for money is determined by the function of money as a stock of value (as a means of preserving value, as a financial asset). However, as a financial asset, money only retains its value (and even then only in a non-inflationary economy), but does not increase it. Cash has absolute (100%) liquidity, but zero return. At the same time there are other types of financial assets, for example, bonds, which generate income as a percentage. Therefore, the higher the interest rate, the more a person loses, keeping cash and not acquiring interest-bearing bonds. Consequently, the determining factor in the demand for money as a financial asset is the interest rate. In this case, the interest rate serves as an alternative cost of storing cash. A high interest rate means a high yield of bonds and high opportunity costs of keeping money on hand, which reduces the demand for cash. With a low rate, i.e. low alternative storage costs of cash, the demand for them increases, because with a low yield of other financial assets, people tend to have more cash, preferring their property of absolute liquidity. Thus, the demand for money is negatively dependent on the interest rate, so the speculative demand for money curve has a negative slope (Fig. 2. (b)). This explanation of the speculative motive of money demand proposed by Keynes is called the theory of liquidity preference. The negative relationship between speculative demand for money and the interest rate can be explained in another way - in terms of the behavior of people in the securities (bonds) market. From the theory of preference for liquidity comes the modern portfolio theory of money. This theory is based on the premise that people form a portfolio of financial assets in such a way as to maximize the income derived from these assets, but minimize the risk. Meanwhile, it is the riskiest assets that bring the greatest return. The theory comes from the already familiar to us idea of the inverse relationship between the price of a bond, which is the discounted amount of future income, and the interest rate, which can be regarded as the rate of discount. The higher the interest rate, the lower the price of the bond. It is profitable for stock speculators to buy bonds at the lowest price, so they exchange their cash, buying bonds, i.e. The demand for cash is minimal. Interest rate can not always keep up the high level. When it starts to fall, the price of bonds rises, and people start selling bonds at higher prices than those at which they bought them, while receiving a difference in prices, which is called capital gain. The lower the interest rate, the higher the price of the bonds and the higher the capital gain, so the more profitable is the exchange of bonds for cash. The demand for cash rises. When the interest rate begins to rise, speculators again begin to buy bonds, reducing the demand for cash. Therefore, the speculative demand for money can be written as: (M / P) D A = (M / P) D = - hR.

The total demand for money consists of transactional and speculative: (M / P) D = (M / P) D T + (M / P) D A = kY - hR, where Y is the real income, R is the nominal interest rate, k - sensitivity (elasticity) of the change in the demand for money to a change in the level of income, i.e. a parameter that shows how much the money demand changes when the income level changes by one, h is the sensitivity (elasticity) of the money demand change to a change in the interest rate, i.e. a parameter that shows how much the money demand changes when the interest rate changes by one percentage point (there is a plus sign in front of the k parameter, because the relationship between the demand for money and the income level is direct, and h is minus (Because the relationship between the demand for money and the interest rate is inverse).

In modern conditions, representatives of the neoclassical trend also recognize that the factor in the demand for money is not only income, but also the interest rate, and the relationship between money demand and interest rate is the opposite. However, they still hold the view that there is a single motive for the demand for money - transactional. And it is precisely the transaction demand that depends on the interest rate. This idea was proposed and proved by two American economists William Baumole (1952) and a Nobel Prize winner James Tobin (1956) and was named the Baumol-Tobin cash management model.

Money supply is the presence of all money in the economy, i.e. this is the money supply. To characterize and measure the money supply, various general indicators are used, the so-called monetary aggregates. In the USA, the money supply is calculated on four monetary aggregates, in Japan and Germany - on three, in England and France - on two. This is due to the peculiarities of the monetary system of this or that country, in particular, the importance of various types of deposits.

However, in all countries the system of monetary aggregates is constructed in the same way: each next aggregate includes the previous one.

Consider the United States monetary aggregate system.

The M1 monetary unit includes cash (paper and metal, i.e., banknotes and coins) (in some countries, cash is allocated into a separate unit, M0) and current accounts (demand deposits), i.e. check deposits or demand deposits.

M1 = cash + check deposits (demand deposits) + travelers checks

The M2 monetary aggregate includes the M1 monetary aggregate and funds on non-chekhovykh savings accounts (save deposits), as well as small (up to $ 100,000) term deposits.

M2 = M1 + savings deposits + small term deposits.

The M3 monetary aggregate includes the M2 monetary aggregate and funds on large (over $ 100,000) term accounts (time deposits).

M3 = M2 + large time deposits + certificates of deposit.

Monetary aggregate L includes monetary aggregate M3 and short-term government securities (mainly treasury bills - treasury bills)

L = M3 + short-term government securities, treasury savings bonds, commercial paper

The liquidity of monetary aggregates increases from bottom to top (from L to M0), and profitability from top to bottom (from M0 to L).

The components of monetary aggregates are divided into: 1) cash and non-cash money and 2) money and near-money (“near-money”)

Cash includes banknotes and coins in circulation, i.e. outside the banking system. These are debt obligations of the Central Bank. All other components of monetary aggregates (i.e. located in the banking system) are non-cash money. These are debt obligations of commercial banks.

Money is only the M1 monetary aggregate (i.e. cash — C (currency), which are liabilities of the Central Bank and have absolute liquidity and zero profitability, and funds in current accounts of commercial banks — D (demand deposits), which are liabilities of these banks) : M = C + D

If funds from savings accounts are easily transferred to current accounts (as in the US), then D will include savings deposits.

M2, M3 and L monetary aggregates are “almost money” because they can be converted into money (because you can: a) either withdraw funds from savings or time accounts and convert them into cash, b) or transfer funds from these accounts on current account, c) or sell government securities).

Thus, the money supply is determined by economic behavior:

Comments

To leave a comment

Macroeconomics

Terms: Macroeconomics