Lecture

A judgment is a thought expressed by a statement.

It is sometimes said that the judgment is true or false. This does not agree well, however, with the customs of our use of a natural, or colloquial, language. We often speak of value judgments, normative judgments, etc., which obviously have no truth value.

The judgment is devoid of the psychological tone inherent in the statement. Although judgment is expressed only in language, it, unlike a sentence, does not depend on a particular language. The message that some judgment was expressed in a particular situation, the ns needs to indicate what language was used. The same judgment can be expressed by different sentences of the same language or different languages. Thus, the phrase "Plavt said that a man is a wolf to a man" states what thought Plavt expressed, but says nothing about what language he used. This idea can be expressed both in Russian and in other languages. But if we say that a specific sentence was expressed by someone, we will not be able to convey our thought until we indicate what language was used. It is true that Plavt made the proposal “Homo homini lupus est”, but it is not true that he once said the sentence “Man to man is wolf”.

This example shows well the difference between judgments and statements: judgment is pure content, while a statement is some content taken together with its language envelope, i.e. offer The judgment can be characterized as something in common that they have two sentences, which are the correct translations of each other.

The term "judgment" is widely used by traditional logic. In modern logic, the term “utterance” is usually used, denoting a grammatically correct sentence, taken together with the meaning expressed by it (“judgment”).

2.1. Judgment as a form of thinking

A judgment ( statement ) is a form of thinking in which something is affirmed or denied. For example: “All pines are trees”, “Some people are athletes”, “Not a single whale is a fish”, “Some animals are not predators” .

Consider several important properties of judgment, which at the same time distinguish it from the concept:

1. Any judgment consists of related concepts.

For example, if we connect the concepts of " crucian " and " fish ", then we can get the proposition: " All crucians are fish", "Some fish are crucians" .

2. Any judgment is expressed in the form of a sentence (remember, a concept is expressed by a word or a phrase). However, not every sentence can express judgment. As you know, sentences are narrative, interrogative and exclamation. In interrogative and exclamatory sentences nothing is affirmed or denied, therefore they cannot express judgment. A narrative sentence, on the contrary, always asserts or denies something, by virtue of which judgment is expressed in the form of a narrative sentence. Nevertheless, there are such interrogative and exclamatory sentences that only in form are questions and exclamations, and in the sense of something they say or deny. They are called rhetorical . For example, the famous saying: “ And what Russian does not like to drive fast? "- is a rhetorical interrogative sentence (rhetorical question), because in it it is stated in the form of a question that every Russian loves fast driving.

There is a judgment in this question. The same can be said about rhetorical exclamations. For example, in the statement: “ Try to find a black cat in a dark room, if it is not there! »- in the form of an exclamation sentence, the idea is affirmed that the proposed action is impossible, by virtue of which this exclamation expresses judgment. It is clear that this is not a rhetorical question, but a real question, for example: “ What is your name? "- does not express judgment, just as it does not express its present, and not a rhetorical exclamation, for example:" Farewell, free elements! ".

3. Any judgment is true or false. If the statement is true, it is true, and if it is not, it is false. For example, the proposition: “ All roses are flowers ,” is true, and the proposition: “ All flies are birds, ” is false. It should be noted that concepts, unlike judgments, cannot be true or false. It is impossible, for example, to say that the concept “ school ” is true, and the concept “ institute ” is false, the concept “ star ” is true, and the concept “ planet ” is false, etc. But perhaps the concepts “ Serpent Gorynych ”, “ Koschey Immortal "," perpetual motion "is not false? No, these concepts are null (empty), but not true or false. Recall that a concept is a form of thinking that designates an object — and that is why it cannot be true or false. Truthfulness or falsity is always a characteristic of a statement, affirmation or denial, therefore it applies only to judgments, not to concepts. Since any judgment takes one of two meanings — truth or falsehood — then Aristotelian logic is also often called two-digit logic .

4. Judgments are simple and complex. Difficult judgments consist of simple, united by any union.

As we can see, judgment is a more complex form of thinking compared to a concept. It is not surprising, therefore, that a judgment has a certain structure in which four parts can be distinguished:

1. The subject (denoted by the Latin letter S ) - this is what is at stake in the judgment. For example, in the judgment: “ All textbooks are books ,” this is a textbook, therefore the notion of “ textbooks ” is the subject of this judgment.

2. Predicate (denoted by the Latin letter P ) - this is what is said about the subject. For example, in the same judgment: “ All textbooks are books ,” the subject (textbooks) states that they are books, therefore the notion of a “ book ” is a predicate of this judgment.

3. A bundle is what connects the subject and the predicate. In the role of bundles may be the words "is", "is", "this", etc.

4. A quantifier is a pointer to the volume of a subject. In the role of the quantifier can be the words "all", "some", "none", etc.

Consider the proposition: " Some people are athletes ." In it, the subject is the concept of “ people ”, the predicate is the concept of “ athletes ”, the word “ are ” plays the role of a bunch, and the word “ some ” is a quantifier. If in some judgment there is no bundle or quantifier, then they are still implied. For example, in the judgment: “ Tigers are predators, ” there is no quantifier, but it is implied — this is the word “all.” With the help of the legend of the subject and the predicate, one can discard the content of the judgment and leave only its logical form.

For example, if the judgment: “ All rectangles are geometric figures ” - drop the content and leave the form, then it turns out: “All S is P ”. The logical form of judgment: “ Some animals are not mammals ”, - “Some S are not P ”.

The subject and the predicate of any judgment always represent any concepts that, as we already know, can be in different relationships with each other. Between the subject and the predicate of judgment there may be the following relationships.

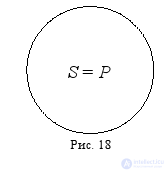

1. Equivalence . In the judgment: “ All squares are equilateral rectangles ”, the subject is “ squares ” and the predicate “ equilateral rectangles ” are in relation to equivalence, because they are equivalent concepts (a square is necessarily an equilateral rectangle, S = P and an equilateral rectangle is necessarily square) (Fig. 18).

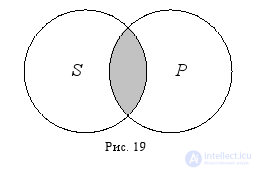

2. Crossing . In the judgment:

“ Some writers are Americans ”, the subject of “ writers ” and the predicate “ Americans ” are in relation to intersection, because they are intersecting concepts (the writer may be American and may not be, and the American may be a writer, but also they will not be) (Fig. 19).

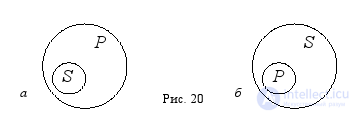

3. Submission . In the judgment:

“ All tigers are predators ”, the subject “ tigers ” and the predicate “ predators ” are in relation to subordination, because they represent a specific and generic concept (a tiger is necessarily a predator, but a predator is not necessarily a tiger). Also in the judgment: “ Some predators are tigers ,” the subject of “ predators ” and the predicate “ tigers ” are in relation to subordination, being generic and species concepts. So, in the case of subordination between the subject and the predicate of judgment, two variants of relations are possible: the volume of the subject is fully included in the volume of the predicate (fig. 20, a ), or vice versa (fig. 20, b ).

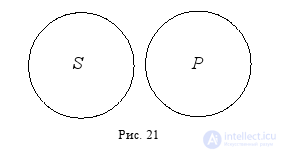

4. Incompatibility . In the judgment: “ All planets are not stars ” - the subject of the “ planet ” and the predicate “ stars ” are in relation to incompatibility, since they are incompatible (co-ordinated) concepts (no planet can be a star, and may be a planet) (Fig. 21).

In order to establish the relation between the subject and the predicate of a judgment, one must first establish which concept of the judgment is the subject and which is the predicate. For example, it is necessary to determine the relationship between the subject and the predicate in the judgment: “ Some soldiers are Russians ”. First we find the subject of the judgment, this is the concept of " military men "; then we set its predicate, this is the notion of “ Russians ”. The terms " servicemen " and " Russians " are in relation to the intersection (the serviceman may be Russian and may not be there, and the Russian may or may not be a serviceman). Consequently, in the indicated judgment, the subject and the predicate intersect. Similarly, in the judgment: “ All the planets are celestial bodies ” - the subject and the predicate are in the relation of submission, and in the judgment: “ Not a single whale is a fish ” - the subject and the predicate are incompatible.

As a rule, all judgments are divided into three types:

1. Attributive judgments (from the Latin. Attributum - attribute) are judgments in which the predicate is some essential, integral feature of the subject. For example, the proposition: “ All sparrows are birds ” is attributive because its predicate is an integral sign of a subject: being a bird is the main sign of a sparrow, its attribute, without which it will not be itself (if some object is not a bird, then he is sure and not a sparrow). It should be noted that in an attributive judgment the predicate is not necessarily an attribute of the subject, it may be the other way round — the subject is an attribute of the predicate. For example, in the judgment: “ Some birds are sparrows ” (as we see, in comparison with the above example, the subject and the predicate are reversed), the subject is an integral feature (attribute) of the predicate. However, these judgments can always be formally modified in such a way that the predicate becomes an attribute of the subject. Therefore, those judgments in which the predicate is an attribute of the subject are usually called attribute.

2. Existential judgments (from Lat. Existentia - existence) are judgments in which the predicate indicates the existence or non-existence of the subject. For example, the judgment: “ There is no perpetual motion ,” is existential, since its predicate “ does not exist ” indicates the non-existence of the subject (or rather, the subject, which is designated by the subject).

3. Relative judgments (from Lat. Relativus - relative) are judgments in which the predicate expresses a relationship with the subject. For example, the judgment: “ Moscow was founded before St. Petersburg ,” is relative, because its predicate “was founded before St. Petersburg ” indicates the temporal (age) relationship of one city and the corresponding concept to another city and the corresponding concept, which is a subject judgments.

1. What is a judgment? What are its main properties and differences from the concept?

2. In what language forms is judgment expressed? Why interrogative and exclamatory sentences can not express a judgment? What are rhetorical questions and rhetorical exclamations? Can they be a form of expression of judgment?

3. Find in the expressions below the language forms of judgments:

1) Did you not know that the earth revolves around the sun?

2) Farewell, unwashed Russia!

3) Who wrote the philosophical treatise Critique of Pure Reason?

4) The logic appeared around the V century. BC er in ancient Greece.

5) The first president of America.

6) Turn around in a march!

7) We all learned a little ...

8) Try to move at the speed of light!

4. Why can concepts, unlike judgments, not be true or false? What is two-digit logic?

5. What is the structure of judgment? Come up with five propositions and specify in each of them a subject, predicate, bundle and quantifier.

6. What are the relations between the subject and the predicate of judgment? Give three examples for each case of the relationship between the subject and the predicate: equivalence, intersection, subordination, incompatibility.

7. Define the relationship between subject and predicate and draw them using Euler’s circular circuits for the following judgments:

1) All bacteria are living organisms.

2) Some Russian writers are world famous people.

3) Textbooks can not be entertaining books.

4) Antarctica is an ice continent.

5) Some mushrooms are inedible.

8. What are attributive, existential and relative judgments? Give, independently picked up, five examples for attributive, existential and relative judgments.

Comments

To leave a comment

Logics

Terms: Logics