Lecture

We now turn to specific sophisms and the problems that stand behind them.

The famous arguments of the ancient Greek philosopher Zeno, Achilles and the Tortoise, Dichotomy, and others, usually called aporia (difficulties), were supposedly directed against the movement and existence of many things. The idea of proving that the world is one and only, and also a fixed thing, seems strange to us today. Strange it seemed and ancient. So strange that the evidence cited by Zeno was immediately attributed to simple tricks, and, moreover, deprived, in general, of a special trick. Such they were considered more than two thousand years, and sometimes are considered now. Let us see how they are formulated, and pay attention to their apparent simplicity and straightforwardness.

The fastest creature is not able to catch up with the slowest, swift-footed Achilles will never overtake the sluggish tortoise. By the time Achilles reaches the tortoise, she will advance a little. He will quickly overcome this distance, but the turtle will go a little further ahead. And so on to infinity. Whenever Achilles reaches the place where the turtle was in front of it, it will turn out to be at least a little bit, but ahead.

In "Dichotomy", attention is drawn to the fact that a moving object must go halfway up its path before it reaches its end. Then he must pass half of the remaining half, then half of this fourth part, and so on. to infinity. The subject will constantly approach the end point, but never will reach it.

This reasoning can be somewhat altered. To go half the way, the object must go through half of this half, and for this you need to go through half of this quarter, etc. The object in the end did not budge.

These seemingly simple arguments are devoted to hundreds of philosophical and scientific works. In them, dozens of different ways prove that the assumption of the possibility of movement does not lead to the absurdity, that the science of geometry is free from paradoxes and that mathematics is capable of describing movement without contradiction.

The abundance of refutations of Zeno’s arguments is significant. Not entirely clear; what exactly are these arguments that they prove. It is not clear how this “something” is proved and is there any proof at all? One feels only that there are some problems or difficulties. And before you refute Zeno, you need to find out exactly what he intended to say and how he substantiated his theses. He himself did not directly formulate either the problems or his solutions to these problems. There is, in particular, only a short story of how Achilles unsuccessfully tried to catch up with the turtle.

The moral extracted from this description depends, naturally, on the wider background against which it is viewed and changed with the change of this background.

The reasoning of Zeno now, one must think, is finally taken out of the category of ingenious tricks. They, according to B. Russell, "in one form or another affect the foundations of almost all theories of space, time and infinity, proposed from its time to the present day."

The commonality of these arguments with other sophisms of the ancients is undoubted. Both those and others have the form of a short story or description of a simple situation at its core, which does not seem to be any special problems. However, the description presents the phenomenon in such a way that it turns out to be clearly incompatible with the well-established notions about it. A sharp discrepancy, even a contradiction, arises between these ordinary ideas about the phenomenon and its description in aporia or sophism. Kick-only it is noticed, the story loses the appearance of a simple and innocuous statement. Behind it opens an unexpected and unclear depth, in which a vague question is guessed, or even many questions. It is difficult to say with certainty what exactly these questions are, they have yet to be clarified and formulated, but it is obvious that they exist. They must be extracted from the story in the same way that morality is extracted from the everyday parable. And as in the case of a parable, the results of thinking about a story in an important way depend not only on himself, but also on the context in which the story is considered. Because of this, questions turn out to be not so much posed as driven by a story. They vary from person to person and from time to time. And there is no certainty that the next couple “question - answer” has exhausted the entire content of the story.

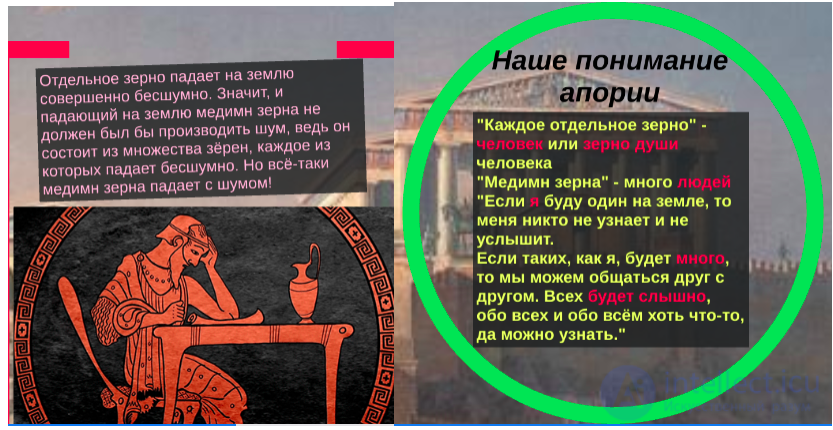

Zeno proposed another sophism - Medim Grain (approximately a bag of grain), which served as the prototype for the famous sophistry of Eubulid Kuch and Lysy.

A large mass of small, millet, for example, grains, when falling to the ground, always produces noise. It consists of the noise of individual grains, and, therefore, every grain and every smallest part of the grain must, when falling, produce noise. However, a single grain falls on the ground completely silently. So, the grain falling to the ground would not have to produce noise, because it consists of a set of grains, each of which falls silently. Still, the grain medimn falls with noise!

In the XIX century. Experimental psychology began to take shape. "Medimn grain" was interpreted as the first vague indication of the existence of just open perception thresholds. This interpretation seems convincing to many today.

A person hears not all sounds, but only those who have attained a certain power. The fall of a single grain produces noise, but it is so weak that it lies outside of human hearing. The fall of many grains gives the noise caught by man. “If Zeno were familiar with the theory of sound,” wrote the German philosopher T. Brentano, “he would not, of course, invent his own argument.”

With such an explanation, one simple, but all-changing circumstance was completely discernible: the sophism “Medimn grains” is strictly analogous to the sophistries “Pile” and “Bald”. But the latter have nothing to do with the theory of sound, or pi to the psychology of hearing.

It means that they need some other and different explanations. And this already seems obviously inconsistent: homophonic sophistries must be resolved in the same way. In addition, once the principle of constructing such sophisms has been grasped, they can be formulated as much as one wishes. It would be naive, however, for each of them to seek some kind of their own solution.

It is clear that references to the psychology of perception do not reflect the essence of the difficulty that is played up by the sophisms in question.

Much more profound is their analysis given by Hegel. The questions: “Does the addition of one grain create a bunch?”, “Does a horse's tail become naked if one hair is pulled out of it?” Seem naive. But the attempt of the ancient Greeks to represent the contradictory nature of any change finds expression in them.

The gradual, imperceptible, purely quantitative change of an object cannot continue indefinitely. At a certain point, it reaches its limit, a dramatic qualitative change occurs, and the object changes to another quality. For example, at temperatures from 0 ° C to 100 ° C, water is a liquid. Its gradual heating ends with the fact that at 100 ° C it boils and abruptly, abruptly, goes into another qualitative state - turns into steam.

“When a quantitative change occurs,” Hegel wrote, “it seems at first completely innocent, but behind this change something else is also hidden, and this seemingly innocent change in quantitative is, as it were, a trick by means of which qualitative is captured.”

Sophisms such as Medim Grain, Pile, Bald are also a good example of the difficulties to which inaccurate or "fuzzy" concepts lead, i.e. concepts referring to fuzzy-defined classes of objects.

The sophistries of "Electra" and "The Plated" are still cited as characteristic specimens of imaginary wisdom.

In one of the tragedies of Evrinid, there is a scene in which Electra and Orest, brother and sister, meet after a very long separation.

Does Electra know her brother? Yes, she knows Orestes. But here he is standing in front of her, unlike the one she had last seen, and she does not know that this man is an Orest. So she knows what she doesn't know?

A close variation on the same topic is “Covered”. I know, say, Sidorov, but I don’t know that he is standing next to me, having covered myself with something. They ask me: “Do you know Sidorov?” My convincing answer will be both true and wrong, since I do not know what kind of person next to me. If he opened, I could say that I just did not recognize him.

Sometimes this sophistry is given a form in which, as it seems, its emptiness and helplessness become especially visual.

- Do you know what I want to ask you now?

- Not.

“Don't you know what to lie is not good?”

- Of course I know.

“But it was about this that I was going to ask you, and you answered that you did not know.”

The point, however, is not in the form of presentation, no matter how empty it may seem. The fact is that such situations of “ignorant” knowledge are common in cognition, and, moreover, not only in the abstract science that has become interested in theorizing, but also in the most elementary acts of cognition. This idea may seem strange to the reader. But do not rush into objections; in the future, simple examples will vividly show that this is indeed the case.

Aristotle tried to resolve such sophisms, referring to the ambiguity of the verb "to know." Indeed, there is a moment of ambiguity. You may know that a lie is reprehensible, and you don’t know exactly what they want to ask about.

But to limit ourselves here to a simple reference to ambiguity means not to understand the depths of ambiguity itself and to miss the most important and interesting.

Can true knowledge of the subject be considered here if they cannot be brought into conformity with the subject itself? This problem is directly behind the sophisms in question. They fix a living contradiction between the presence of knowledge about the subject and the identification of the subject. The whole history of theoretical science, and especially the development of modern, usually highly abstract, spiders speaks about how important such a contradiction is.

Truth is an endless approach to its object. By identifying our knowledge of a particular subject with a particular subject, we thereby change and deepen it. Obviously, the specific application of knowledge requires the recognition of the subject, and it is not surprising that recognition is an important component of cognitive activity.

There is always a discrepancy between the prevailing ideas about the studied fragment of reality and the fragment itself. In the case of a scientific theory, this is a discrepancy or mismatch between the theoretical ideas about the objects under study and the empirical objects themselves, which are given in experience. This discrepancy is especially great at the initial stages of the study, when a number of theoretical conclusions have not yet been able to match any empirical data.

A good example of this is the prediction by the outstanding Russian chemist D. Mendeleev of the existence of new chemical elements. Since empirically they were not yet open and existed only in the “theoretical space”, which itself was not yet firm and had no distinct outlines, D. Mendeleev did not dare to publish his prediction for several years.

A typical example, already related to modern physics, is a prediction in the early 1930s. XX century. English physicist P. Dirac existence of an elementary neutrino particle. Physicists immediately agreed that the introduction of this "highly theoretical" particle was useful and perhaps even necessary from the point of view of theory. After only about two decades later, direct traces of neutrinos could be found in scintillation chambers. The theory gave some knowledge about this particle, but it took a relatively long period of time, until it was finally supplemented by the identification of the particle itself. Purely theoretical knowledge until that time was from that moment connected with empirical phenomena and thus "objectified."

The discrepancy between the theoretical inference and the empirical result always means the existence of “unforeseeable” knowledge or knowledge about “unidentified” objects, which was figuratively called “unaware” knowledge. Sophisms, like "Covered", just pay attention to the possibility and, in general, the usualness of such knowledge.

They also raise the question of what constitutes the truth criterion of theoretical statements whose objects have not yet been discovered in reality or do not exist at all, like an absolutely black body or an ideal gas.

True is the thought corresponding to the object it describes. But if this object is unknown, with what should thought be compared for judging its truth? The answer to this question is complex and causes a lot of controversy in the modern methodology of science.

This and other problems can be read from the discussed sophisms only with a sufficiently high level of scientific knowledge and knowledge of this knowledge itself. For these problems, albeit in the most “germinal” and allegorical form, they nevertheless were raised by these sophisms.

As for the ambiguity of the word “to know,” as well as ambiguity in general, it should be noted that it is far from always an annoying mistake of a separate, insufficiently consistent mind. Ambiguity can be not only subjective, being an expression of some logical lack of training. The discrepancy between the theoretical and the empirical is a constant and completely objective source of uncertainty and ambiguity.

Comments

To leave a comment

Logics

Terms: Logics