Lecture

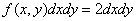

So far, we have considered physical systems whose various states  it was possible to list everything; the probabilities of these states were some nonzero magnitudes

it was possible to list everything; the probabilities of these states were some nonzero magnitudes  . Such systems are similar to discontinuous (discrete) random variables, taking values

. Such systems are similar to discontinuous (discrete) random variables, taking values  with probabilities

with probabilities  . In practice, physical systems of a different type are often encountered, similar to continuous random variables. The states of such systems cannot be renumbered: they continuously go from one to another, with each individual state having a probability equal to zero, and the probability distribution is characterized by a certain density. Such systems, by analogy with continuous random variables, we will call "continuous", in contrast to the previously considered, which we will call "discrete". The simplest example of a continuous system is a system whose state is described by one continuous random variable.

. In practice, physical systems of a different type are often encountered, similar to continuous random variables. The states of such systems cannot be renumbered: they continuously go from one to another, with each individual state having a probability equal to zero, and the probability distribution is characterized by a certain density. Such systems, by analogy with continuous random variables, we will call "continuous", in contrast to the previously considered, which we will call "discrete". The simplest example of a continuous system is a system whose state is described by one continuous random variable.  with distribution density

with distribution density  . In more complex cases, the state of the system is described by several random variables.

. In more complex cases, the state of the system is described by several random variables.  with distribution density

with distribution density  . Then it can be considered as an association.

. Then it can be considered as an association.  simple systems

simple systems  .

.

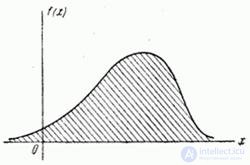

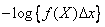

Consider a simple system.  defined by one continuous random variable

defined by one continuous random variable  with distribution density

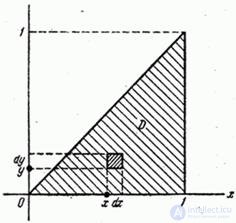

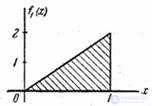

with distribution density  (fig. 18.7.1). We will try to extend to this system entered in

(fig. 18.7.1). We will try to extend to this system entered in  18.1 the concept of entropy.

18.1 the concept of entropy.

Fig. 18.7.1.

First of all, we note that the concept of a “continuous system,” like the concept of a “continuous random variable,” is a kind of idealization. For example, when we consider the value  - growth at random taken by a person - a continuous random variable, we are distracted from the fact that no one actually measures growth more precisely than 1 cm, and that it is almost impossible to distinguish between two growth values that differ, say, by 1 mm. Nevertheless, it is natural to describe this random variable as continuous, although it could be described as discrete, considering those values that differ by less than 1 cm to coincide.

- growth at random taken by a person - a continuous random variable, we are distracted from the fact that no one actually measures growth more precisely than 1 cm, and that it is almost impossible to distinguish between two growth values that differ, say, by 1 mm. Nevertheless, it is natural to describe this random variable as continuous, although it could be described as discrete, considering those values that differ by less than 1 cm to coincide.

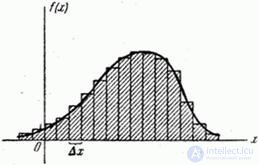

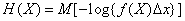

Similarly, by setting the limit of measurement accuracy, i.e., some segment  within which the system state

within which the system state  practically indistinguishable, you can approximate a continuous system

practically indistinguishable, you can approximate a continuous system  to discrete. This is equivalent to replacing a smooth curve.

to discrete. This is equivalent to replacing a smooth curve.  step type histogram (Fig. 18.7.2); at the same time each section (discharge) of length

step type histogram (Fig. 18.7.2); at the same time each section (discharge) of length  replaced by one representative point.

replaced by one representative point.

Fig. 18.7.2.

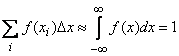

The squares of the rectangles represent the probabilities of hitting the corresponding bits:  . If we agree to consider indistinguishable system states belonging to the same category, and combine them all into one state, then we can approximately determine the entropy of the system

. If we agree to consider indistinguishable system states belonging to the same category, and combine them all into one state, then we can approximately determine the entropy of the system  considered up to

considered up to  :

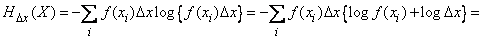

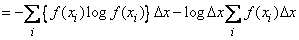

:

. (18.7.1)

. (18.7.1)

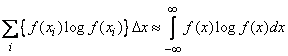

When small enough  :

:

,

,

and the formula (18.7.1) takes the form:

. (18.7.2)

. (18.7.2)

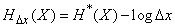

Note that in expression (18.7.2), the first term turned out to be completely independent of  - the degree of accuracy in determining system states. Depends on

- the degree of accuracy in determining system states. Depends on  only second member

only second member  which tends to infinity when

which tends to infinity when  . This is natural, since the more precisely we want to set the state of the system

. This is natural, since the more precisely we want to set the state of the system  , the greater degree of uncertainty we need to eliminate, and with unlimited reduction

, the greater degree of uncertainty we need to eliminate, and with unlimited reduction  this uncertainty grows unlimited too.

this uncertainty grows unlimited too.

So, asking an arbitrarily small "insensitivity area"  our measuring instruments, which determine the state of the physical system

our measuring instruments, which determine the state of the physical system  entropy can be found

entropy can be found  by the formula (18.7.2), in which the second term grows indefinitely with decreasing

by the formula (18.7.2), in which the second term grows indefinitely with decreasing  . Entropy itself

. Entropy itself  differs from this unlimitedly growing member by independent of

differs from this unlimitedly growing member by independent of  magnitude

magnitude

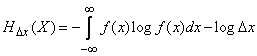

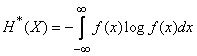

. (18.7.3)

. (18.7.3)

This value can be called the “reduced entropy” of a continuous system.  . Entropy

. Entropy  expressed through reduced entropy

expressed through reduced entropy  by formula

by formula

. (18.7.4)

. (18.7.4)

The ratio (18.7.4) can be interpreted as follows: on the measurement accuracy  depends only on the origin, at which the entropy is calculated.

depends only on the origin, at which the entropy is calculated.

In the future, to simplify the record, we will omit the index  in the designation of entropy and write just

in the designation of entropy and write just  ; Availability

; Availability  the right side will always indicate the accuracy of which.

the right side will always indicate the accuracy of which.

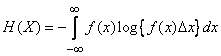

Formula (18.7.2) for entropy can be given a more compact form, if, as we did for discontinuous quantities, we write it in the form of the mathematical expectation of a function. First of all, we rewrite (18.7.2) as

. (18.7.5)

. (18.7.5)

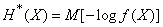

This is nothing more than the expectation of a function.  from random variable

from random variable  with density

with density  :

:

. (18.7.6)

. (18.7.6)

A similar form can be given to  :

:

. (18.7.7)

. (18.7.7)

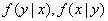

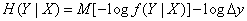

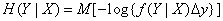

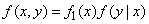

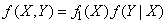

Let us proceed to the definition of conditional entropy. Suppose there are two continuous systems:  and

and  . In general, these systems are dependent. Denote

. In general, these systems are dependent. Denote  distribution density for states of the combined system

distribution density for states of the combined system  ;

;  - system distribution density

- system distribution density  ;

;  - system distribution density

- system distribution density  ;

;  - conditional density of distribution.

- conditional density of distribution.

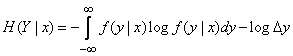

First, we define the partial conditional entropy.  i.e. system entropy

i.e. system entropy  provided that the system

provided that the system  took a certain state

took a certain state  . The formula for it will be similar (18.4.2), only instead of conditional probabilities

. The formula for it will be similar (18.4.2), only instead of conditional probabilities  there will be conditional distribution laws

there will be conditional distribution laws  and a term will appear

and a term will appear  :

:

. (18.7.8)

. (18.7.8)

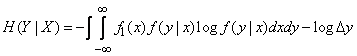

We now turn to the full (average) conditional entropy  , for this you need to average private conditional entropy

, for this you need to average private conditional entropy  in all states

in all states  taking into account their probabilities, characterized by a density

taking into account their probabilities, characterized by a density  :

:

(18.7.9)

(18.7.9)

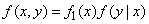

or, considering that

,

,

. (18.7.10)

. (18.7.10)

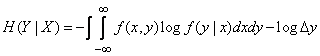

Otherwise, this formula can be written as

(18.7.11)

(18.7.11)

or

. (18.7.12)

. (18.7.12)

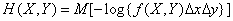

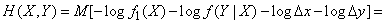

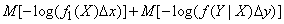

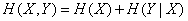

Having thus determined the conditional entropy, let us show how it is used in determining the entropy of the combined system.

We first find the entropy of the combined system directly. If “dead spots” for systems  and

and  will be

will be  and

and  then for a unified system

then for a unified system  the elementary rectangle will play their role

the elementary rectangle will play their role  . Entropy system

. Entropy system  will be

will be

. (18.7.13)

. (18.7.13)

Because

,

,

then and

. (18.7.14)

. (18.7.14)

Let's substitute (18.7.14) in (18.7.13):

,

,

or, according to the formulas (18.7.6) and (18.7.12)

, (18.7.15)

, (18.7.15)

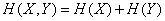

that is, the entropy theorem of a complex system also holds for continuous systems.

If a  and

and  are independent, the entropy of the combined system is equal to the sum of the entropies of the constituent parts:

are independent, the entropy of the combined system is equal to the sum of the entropies of the constituent parts:

. (18.7.16)

. (18.7.16)

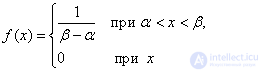

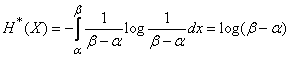

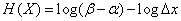

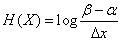

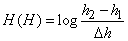

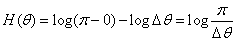

Example 1. Find the entropy of a continuous system  , which all states on some site

, which all states on some site  equally likely:

equally likely:

Decision.

;

;

or

. (18.7.17)

. (18.7.17)

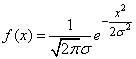

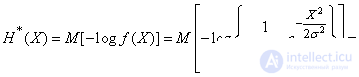

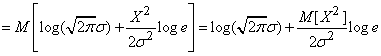

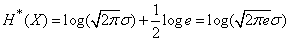

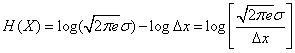

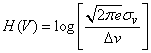

Example 2. Find the entropy of the system  The states of which are distributed according to the normal law:

The states of which are distributed according to the normal law:

.

.

Decision.

.

.

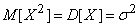

But

,

,

and

. (18.7.18)

. (18.7.18)

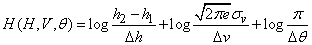

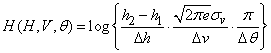

Example 3. The condition of the aircraft is characterized by three random variables: height  , speed module

, speed module  and angle

and angle  determining the direction of flight. The height of the aircraft is distributed with a uniform density on the site

determining the direction of flight. The height of the aircraft is distributed with a uniform density on the site  ; speed

; speed  - under the normal law with m.

- under the normal law with m.  and s.ko.

and s.ko.  ; angle

; angle  - with uniform density on the site

- with uniform density on the site  . Values

. Values  are independent. Find the entropy of the combined system.

are independent. Find the entropy of the combined system.

Decision.

From example 1 (formula (18.7.17)) we have

,

,

Where  - “deadband” when determining the height.

- “deadband” when determining the height.

Так как энтропия случайной величины не зависит от ее математического ожидания, то для определения энтропии величины  воспользуемся формулой (18.7.18):

воспользуемся формулой (18.7.18):

.

.

Энтропия величины  :

:

.

.

Finally we have:

or

. (18.7.19)

. (18.7.19)

Заметим, что каждый из сомножителей под знаком фигурной скобки имеет один и тот же смысл: он показывает, сколько «участков нечувствительности» укладывается в некотором характерном для данной случайной величины отрезке. В случае распределения с равномерной плотностью этот участок представляет собой просто участок возможных значений случайной величины; в случае нормального распределения этот участок равен  where

where  - среднее квадратическое отклонение.

- среднее квадратическое отклонение.

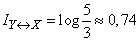

Таким образом, мы распространили понятие энтропии на случай непрерывных систем. Аналогично может быть распространено и понятие информации. При этом неопределенность, связанная с наличием в выражении энтропии неограниченно возрастающего слагаемого, отпадает: при вычислении информации, как разности двух энтропий, эти члены взаимно уничтожаются. Поэтому все виды информации, связанные с непрерывными величинами, оказываются не зависящими от «участка нечувствительности»  .

.

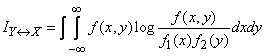

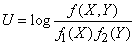

Выражение для полной взаимной информации, содержащейся в двух непрерывных системах  and

and  , будет аналогично выражению (18.5.4), но с заменой вероятностей законами распределения, а сумм - интегралами:

, будет аналогично выражению (18.5.4), но с заменой вероятностей законами распределения, а сумм - интегралами:

(18.7.20)

(18.7.20)

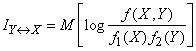

или, применяя знак математического ожидания,

. (18.7.21)

. (18.7.21)

Полная взаимная информация  как и в случае дискретных систем, есть неотрицательная величина, обращающаяся в нуль только тогда, когда системы

как и в случае дискретных систем, есть неотрицательная величина, обращающаяся в нуль только тогда, когда системы  and

and  are independent.

are independent.

Пример 4. На отрезке  выбираются случайным образом, независимо друг от друга, две точки

выбираются случайным образом, независимо друг от друга, две точки  and

and  , каждая из них распределена на этом отрезке с равномерной плотностью. В результате опыта одна из точек легла правее, другая - левее. Сколько информации о положении правой точки дает значение положения левой?

, каждая из них распределена на этом отрезке с равномерной плотностью. В результате опыта одна из точек легла правее, другая - левее. Сколько информации о положении правой точки дает значение положения левой?

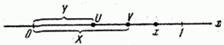

Decision. Рассмотрим две случайные точки  and

and  на оси абсцисс

на оси абсцисс  (рис. 18.7.3).

(рис. 18.7.3).

Fig. 18.7.3.

Denote  абсциссу той из них, которая оказалась слева, а

абсциссу той из них, которая оказалась слева, а  - абсциссу той, которая оказалась справа (на рис. 18.7.3 слева оказалась точка

- абсциссу той, которая оказалась справа (на рис. 18.7.3 слева оказалась точка  , но могло быть и наоборот). Values

, но могло быть и наоборот). Values  and

and  определяются через

определяются через  and

and  следующим образом

следующим образом

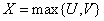

;

;  .

.

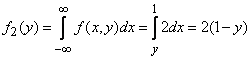

Найдем закон распределения системы  . Because

. Because  , it will exist only in the region

, it will exist only in the region  shaded in fig. 18.7.4.

shaded in fig. 18.7.4.

Fig. 18.7.4.

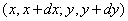

Denote  the distribution density of the system

the distribution density of the system  and find the element of probability

and find the element of probability  , that is, the probability that a random point

, that is, the probability that a random point  falls into an elementary rectangle

falls into an elementary rectangle .This event can occur in two ways: either there is a dot on the left and a dot

.This event can occur in two ways: either there is a dot on the left and a dot  on the right

on the right  , or vice versa. Consequently,

, or vice versa. Consequently,

,

,

Where  marked density distribution of the system of values

marked density distribution of the system of values  .

.

In this case

,

,

Consequently,

;

;

and

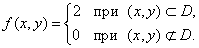

We now find the laws of the distribution of individual quantities in the system:

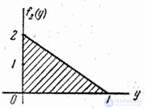

at

at  ;

;

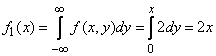

similarly

at

at  .

.

Density graphs  and

and  shown in fig. 18.7.5.

shown in fig. 18.7.5.

Figure 18.7.5.

Substituting  ,

,  and

and  in the formula (18.7.20), we get

in the formula (18.7.20), we get

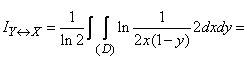

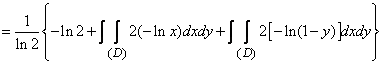

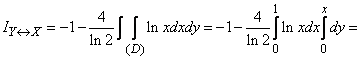

.

.

By virtue of the symmetry of the problem, the last two integrals are equal, and

(two units).

(two units).

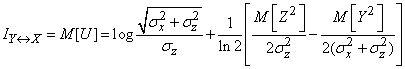

Example 5. There is a random variable  distributed according to the normal law with parameters

distributed according to the normal law with parameters ,

,  . Magnitude

. Magnitude  измеряется с ошибкой

измеряется с ошибкой  , тоже распределенной по нормальному закону с параметрами

, тоже распределенной по нормальному закону с параметрами  ,

,  . Mistake

. Mistake  does not depend on

does not depend on  . В нашем распоряжении - результат измерения, т. е. случайная величина

. В нашем распоряжении - результат измерения, т. е. случайная величина

Определить, сколько информации о величине  содержит величина

содержит величина  .

.

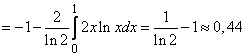

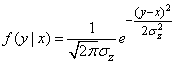

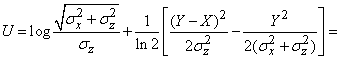

Decision. Воспользуемся для вычисления информации формулой (18.7.21), т. е. найдем ее как математическое ожидание случайной величины

. (18.7.22)

. (18.7.22)

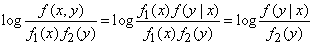

Для этого сначала преобразуем выражение

.

.

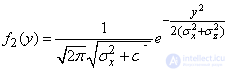

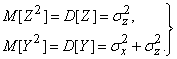

In our case

,

,

(см. главу 9).

(см. главу 9).

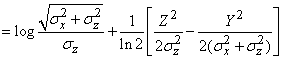

Выражение (18.7.22) равно:

.

.

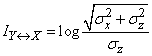

From here

. (18.7.23)

. (18.7.23)

Ho  , Consequently,

, Consequently,

(18.7.24)

(18.7.24)

Подставляя (18.7.24) в (18.7.23), получим

(two units).

(two units).

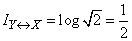

For example, when

(two units).

(two units).

If a  ;

;  then

then  (two units).

(two units).

Comments

To leave a comment

Information and Coding Theory

Terms: Information and Coding Theory