Lecture

Это продолжение увлекательной статьи про восприятие.

...

parts. In order to see the details, they have to set themselves a special task, the fulfillment of which is sometimes given to them with difficulty.

Persons with a different type of perception — detailing, or analytic — on the contrary, tend to clearly distinguish details and details. That is what their perception is directed to. The subject or phenomenon as a whole, the general meaning of what was perceived, fade into the background for them, sometimes not even being noticed. In order to understand the essence of the phenomenon or adequately perceive any object, they need to set themselves a special task, which they are not always able to accomplish. Their stories are always filled with details and descriptions of private details, behind which the meaning of the whole is very often lost.

The above characteristics of the two types of perception are characteristic of the extreme poles. Most often they complement each other, because the most productive perception, based on the positive characteristics of both types. However, even extreme options cannot be viewed as negative, since very often they determine the peculiarity of perception, which allows a person to be an extraordinary person.

There are other types of perception, such as descriptive and explanatory. Descriptive persons are limited to the factual side of what they see and hear, do not try to explain to themselves the essence of the perceived phenomenon. The driving forces of the actions of people, events or any phenomena remain outside their field of attention. In contrast, persons of the explanatory type are not satisfied with what is directly given in perception. They always seek to explain what they see or hear. This type of behavior is often combined with a holistic, or synthetic, type of perception.

Also distinguish objective and subjective types of perception. For an objective type of perception is characterized by strict compliance with what is happening in reality. Persons with a subjective type of perception go beyond what they actually were given, and bring in a lot from themselves. Their perception is subordinated to the subjective attitude to what is perceived, to the increased bias of the assessment, the prevailing prejudice attitude. Such people, telling about something, are inclined to convey not what they perceived, but their subjective impressions about it. They talk more about what they felt or what they thought at the time of the events they are talking about.

Of great importance among individual differences in perception are differences in observation.

Observation is the ability to notice in objects and phenomena that which is not very noticeable in them, is not evident by itself, but that is significant or characteristic from any point of view. A characteristic sign of observation is the speed with which something hardly noticeable is perceived. Observations

Not all people are alike in the same degree. Differences in observation largely depend on the individual characteristics of the individual. For example, curiosity is a factor contributing to the development of observation.

Since we have touched upon the problem of observation, it should be noted that there are differences in perception in the degree of intentionality. It is customary to distinguish unintended (or involuntary) and intentional (arbitrary) perception. With an unintended perception, we are not guided by a predetermined goal or task - to perceive this subject. Perception is guided by external circumstances. Intentional perception, on the contrary, is regulated from the very beginning by a task - to perceive a particular object or phenomenon, to become familiar with it. Deliberate perception can be included in any activity and carried out in the course of its implementation. But sometimes perception can act as a relatively independent activity. Perception as an independent activity is particularly clearly seen in observation, which is deliberate, systematic, and more or less prolonged (albeit intermittently) perception in order to trace the course of a phenomenon or the changes that occur in the object of perception. Therefore, observation is an active form of human perception of reality, and observation can be viewed as a characteristic of perceptual activity.

The role of observation activity is extremely important. It is expressed both in the mental activity accompanying the observation and in the motor activity of the observer. Operating with objects, acting with them, a person knows better many of their qualities and properties. For the success of observation is important its systematic and systematic. Good observation, aimed at a broad, versatile study of the subject, is always carried out according to a clear plan, a certain system, with consideration of some parts of the subject after the others in a certain sequence. Only with this approach, the observer will not miss anything and will not return a second time to what was perceived.

However, observation, as well as perception as a whole, is not an innate characteristic. A newborn child is not able to perceive the world around him as a complete objective picture. The ability of subject perception in a child appears much later. The child’s initial release of objects from the outside world and their objective perception can be judged by the child’s looking at these objects, when he is not just looking at them, but looking at them, as if feeling his eyes.

According to B. M. Teplova, signs of objective perception in a child begin to manifest themselves at an early infancy (two to four months), when actions with objects begin to form. By five or six months, the child has an increase in cases of fixing the gaze on the object with which he operates. However, this development of perception does not stop, but, on the contrary, is just beginning. So, according to A.V. Zaporozhets, the development of perception is carried out at a later age. In the transition from preschool to preschool age, under the influence of play and constructive activity in children, complex types of visual analysis and synthesis, including the ability

mentally dismembering the perceived object into parts in the visual field, examining each of these parts separately and then combining them into one whole.

In the process of teaching a child at school, perception develops actively, which during this period passes through several stages. The first stage is associated with the formation of an adequate image of the object in the process of manipulating this object. At the next stage, children learn about the spatial properties of objects using hand and eye movements. At the next, higher levels of mental development, children acquire the ability to quickly and without any external movements recognize certain properties of perceived objects, to distinguish them on the basis of these properties from each other. Moreover, in the process of perception, no actions or movements take part.

One may ask, what is the most important condition for the development of perception? Such a condition is labor, which in children can manifest itself not only in the form of socially useful labor, for example, in carrying out their household duties, but also in the form of drawing, modeling, playing music, reading, etc., i.e. in the form of a diverse cognitive subject activities. No less important for the child to participate in the game. During the game, the child expands not only his movement experience, but also the idea of the objects around him.

The next, no less interesting question that we must ask ourselves is the question of how and in what ways are the features of children's perception in comparison with an adult? First of all, the child makes a large number of errors in assessing the spatial properties of objects. Even a linear eye in children is much worse developed than in an adult. For example, when perceiving the length of a line, a child’s error may be about five times larger than that of an adult. Even more difficult for children is the perception of time. It is very difficult for a child to master such concepts as “tomorrow”, “yesterday”, “earlier”, “later”.

Certain difficulties arise in children with the perception of images of objects. So, considering a drawing, telling what is painted on it, children of preschool age often make mistakes in recognizing the depicted objects and call them incorrectly, relying on random or insignificant signs.

An important role in all these cases is played by the lack of knowledge of the child. small his practical experience. This also determines a number of other features of children's perception: an insufficient ability to single out the main thing in what is perceived; omission of many parts; limited perception of information. Over time, these problems are eliminated, and by the senior school age, the child’s perception is almost the same as that of an adult.

At each moment of time many objects act on our sense organs, but not all of them are perceived in the same way. Some of them stand out by us, act "to the fore", and we focus on them. Others - like waste

They are “in the background,” in a certain sense, merging with each other, perceived less clearly. In accordance with these, an object is distinguished , or an object, perceptions, i.e., what the perception is focused on at the moment, and the background, which is formed by all other objects acting on us at the same time, but receding, compared to the object perception, "into the background."

In order to visualize the essence of this problem, we will give a few examples. When we take a book out of the bookcase, we perceive many other books, but the subject, or object, of perception is only the book that we need at the moment and that we are looking for. All other books are perceived by us only as a background. The same thing happens in other modes of perception. For example, we go and talk to someone. At the same time, we hear the words of not only our interlocutor, but also many other sounds. However, the words of the person speaking are perceived by us more clearly as an object, and all other sounds are perceived less clearly, that is, they are the background.

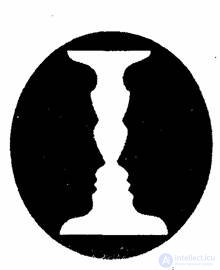

Initially, the difference between the figure (the subject) and the background arose in the visual arts. In psychology, this problem was first seen as an independent Danish psychologist E. Rubin. It is accepted to call a figure a closed, protruding, attracting the attention part of the phenomenological field, and everything that surrounds the figure is the background.

It should be noted that the ratio of the subject and background is a dynamic relationship. What is currently related to the background may, after some time, become an object, and vice versa, what was an object may become a background. This is confirmed by the following example. In fig. 8.3 a white vase is depicted against the background of a black circle, but if you look closely at this picture, you can see that the background also has a certain meaning. In another case, you can see that it is not the vase that is depicted, but the profiles of human faces.

Fig. 8.3 Shape and Background

The selection of an object from the background is connected with the peculiarities of our perception, namely with the objectiveness of perception. We select an object from the background in order to become better acquainted with it, but this selection does not always happen. It is easier to distinguish what is actually a separate subject and is well known from past experience. We easily select things. that surround us, people, animals, etc., separate parts of the subject stand out much worse. In this case, it often takes effort to perceive the part as a special object. For example, we do not immediately select a part of the word that we read, or a part of any drawing that we are considering. It is precisely on this that the tasks found in children's magazines are constructed in which it is necessary to find the difference between two similar drawings.

The selection of an object from the background depends primarily on the degree of difference between them. The more subject And background differ from each other, the easier the subject

stands out from the background. For example, a significant role is played by the difference in color between the background and the subject. Contrast colors are particularly favorable for highlighting an object from the background. Thus, the word written in chalk on the blackboard can be clearly seen and completely unnoticed by the correction in the student's notebook, made by the teacher with the same ink that the student writes.

The selection of the subject is also difficult if the subject is surrounded by similar objects. For example, it is rather difficult to trace the course of a river on a map if it is surrounded by other rivers. Therefore, in order to facilitate the selection of an object from the background, it is necessary to strengthen its difference. Conversely, where it is necessary to impede the selection of an object from the background, it is necessary to reduce their difference.

Fig. 8.3. Transformation of the figure "The figure and background"

Selecting an object from the background makes it easy, firstly, to know what needs to be found, especially if it is a specific image of the object. Secondly, the selection of the object from the background makes it easier to draw around the contours of the object or to move the objects by hand, i.e. the possibility of manipulating objects. Thirdly, the selection of the subject from the background facilitates the experience of such activities.

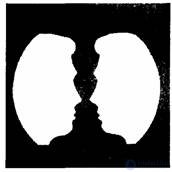

To confirm our words, let's transform Figure 8.3 in a special way. Change the colors on it to the opposite and make some changes to the image (Fig. 8.4). As a result, profiles of human faces come to the fore for most observers, and the vase becomes almost imperceptible. This is due to the fact that, firstly, you are already familiar with the version of this figure and are ready to meet with its modifications; secondly, we changed the color ratio; thirdly, we partially changed the phenomenological field of our perception by changing the shape of the vase.

Each item is a complex whole and has many properties. Perceiving it as a whole, we also perceive its separate parts. Both of these aspects of perception are intimately connected with each other: the perception of the whole is due to the perception of its parts and properties, at the same time it itself affects their perception.

Хорошо известно, как сильно меняется иногда восприятие предмета, если мы пропустим только одну его часть, или подметим ее неправильно, или воспримем как его часть то, что в действительности к нему не имеет никакого отношения. Во всех этих случаях мы легко можем принять предмет за то, чем он фактически не является. Например, при быстром взгляде на слово, сходное с другими словами

Fig. 8.5. Роль части в восприятии целого. В рисунках, где сохранены опознавательные признаки, объект легко узнается

(например «пол», сходное с «кол», «вол» и др.) и написанное отдельно, вне какого-либо контекста, мы легко можем прочитать его неверно (вместо «пол» — «гол»), если только одна из его букв будет написана недостаточно четко (в данном случае «п»).

Важность роли восприятия части в восприятии целого не означает, что для узнавания предмета необходимо воспринимать все его части. Многое из того, что имеется в объекте, совсем не воспринимается, или воспринимается неясно, или не может быть воспринято в данный момент, но тем не менее мы узнаем предмет. Например, когда мы рассматриваем рисунок, схематически изображающий предмет, мы узнаем этот предмет (рис. 8.5). Это происходит потому, что каждый предмет имеет характерные, только ему присущие опознавательные признаки. Отсутствие именно этих признаков в восприятии мешает нам опознать предмет, в то же время отсутствие других, менее существенных признаков при наличии в восприятии существенных не мешает узнать то, что мы воспринимаем.

Данное положение верно не только по отношению к рисункам, но и по отношению к другим явлениям. Например, приведем слово, в котором отдельные буквы пропущены:

<..ек..и. ест.о»

Вряд ли вам сразу удастся узнать это слово, потому что в нем пропущены буквы, являющиеся опознавательными признаками. Теперь попробуем прочитать это

слово при условии, что в нем будут отсутствовать несущественные детали, а опознавательные признаки будут присутствовать:

«эле ...ич... во»

Конечно, это слово теперь узнаваемо. Это слово «электричество». Мы рассмотрели влияние восприятия отдельных частей на восприятие целого. Теперь давайте спросим себя, в чем выражается влияние, которое оказывает восприятие целого на восприятие его отдельных частей и на выделение различных сторон предмета? Это влияние обнаруживается прежде всего в том, что, воспринимая целое, мы не замечаем иногда отсутствия в нем некоторых его частей или, наоборот, наличия того, что в действительности к нему не должно относиться. Не замечаем мы иногда и искажения отдельных частей предмета. Например, общеизвестно, что при чтении мы иногда не замечаем опечаток в тексте: пропусков букв, лишних букв, замены одной буквы другой. Объясняется это тем, что при высоком уровне навыка чтения каждое слово воспринимается как целое, и это влияет на восприятие его отдельных частей, делает их восприятие менее отчетливым.

The relationship of perception of the whole and the part is not the same at different stages of familiarization with the subject. And a significant role is played here by individual differences of people. The initial period of perception in most people is characterized by the fact that the perception of the whole comes to the fore, without isolating individual parts. For some people, the opposite is true: the individual parts of the subject are primarily distinguished.

In accordance with individual differences, the second stage of perception proceeds in different ways. If at first the general form of the object is perceived without a clear distinction between its individual parts, then in the future parts of the object are perceived more clearly. Conversely, if only parts of the object were originally distinguished, then it is made to go to the whole. In the end, in both cases, perception is achieved as a whole with a fairly clear distinction between its individual parts.

|

|

However, it should be noted that the perception of the whole and its parts depends not only on individual characteristics, but also on a number of other factors. First of all, it is necessary to include prior experience and installation among them. For example, we read the text fluently, often skipping errors and typos, because

Fig. 8.6. "Portrait of a Young Woman"

we have sufficient experience in reading, that is, we know the meaning of the words we perceive and we single out the letters from the whole word that serve as identification signs. But if you offer to find an error in the text, then you will carefully look at the spelling of words, while in certain cases you will not even delve into the meaning of what is written. Therefore, installation plays a very important role in the organization of your perception.

This can be illustrated by another example. So, on fig. 8.6. presented "Portrait of a young woman"; Considering this picture, a person first of all sees the elegant profile of a young girl turned away from the observer. However, the secret of this picture lies in the fact that it belongs to the category of so-called ambiguous images. In fact, in this picture, two “portraits” are embodied in one image. The drawing contains not only the image of a young woman, but also an old woman. You can easily see this if you mentally imagine instead of the graceful profile of a girl turned away from you a big hunchbacked nose of an old woman, and instead of a small elegant ear you will see the eye of an old woman. A graphic confirmation of this vision of the “Portrait of a young woman” is rice. 8.7, which presents two images created from Fig. 8.6. The essential feature of these images is that the identification signs characterizing the image of an old woman and a girl are presented separately from each other. In this case, option A corresponds to the image of a young girl, and option B to the image of an old woman.

Why most people in pic. 8.6 first of all see the girl? This is not only because most of us initially perceive

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8.7. Transformation of the image “Portrait of a young woman” into two drawings “Portrait of a young woman” (A) and “Portrait of an old woman * (B), obtained by •“ separating ”identification signs

the image as a whole, but also because the image is called “Portrait of a Young Woman”. Having named the image in this way, we formed an attitude to the observer to perceive this pattern as an image of a young woman. If you present this picture without a specific name, then there may be various options in its interpretation.

To form the installation of perception is possible not only using the name of the object or image. Another way is to use prior experience. For example, if you show the subject fig. 8.7, option B (“Portrait of an Old Woman”), then, of course, he can easily characterize him as an image of an old woman. If after this you show the subject fig. 8.6, while not mentioning it in any way, the majority of subjects will easily see the image of an old woman. If, on the other hand, you do the opposite, that is, if you show variant A initially, then the subjects are easily in Figure 8.6. will see "Portrait of a young woman." Thus, the perception of the whole and the part really depends on many factors. Moreover, the features of perception of individual parts and the whole very significantly influence the character and content of the perceived object or phenomenon.

The perception of space and time occupies a special place among all that we perceive. All objects are in space, and every phenomenon exists in time. Spatial properties are inherent in all objects, as well as temporal characteristics are characteristic of each phenomenon or event.

The spatial properties of the object include: size, shape, position in space.

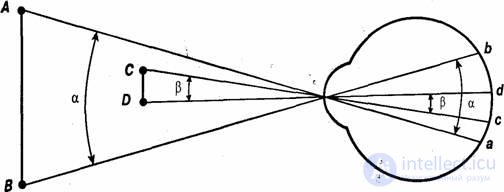

In the perception of the size of an object, the size of its image on the retina plays a significant role. The larger the image of the object on the retina, the larger the subject seems to us. It is likely that the magnitude of the image of the perceived object on the retina depends on the magnitude of the visual angle. The greater the magnitude of the visual angle, the larger the image on the retina. It is generally accepted that the law of the visual angle as a law of perception of size is

Fig. 8.8. The ratio of the magnitude of the visual angle and the size of the image of the object on the retina

Wing Euclid. From this law, it follows that the perceived size of an object varies in direct proportion to the size of its retinal image (Fig. 8.8).

It is logical that this pattern is maintained at the same distance from us objects. For example, if a long pole is twice as far from us as a stick, which is two times shorter than a pole, the angle of view, at which we see these objects, is the same and their images on the retina are equal to each other. In this case, one would assume that we would perceive the stick and the pole as objects of equal size. However, in practice this does not happen. We clearly see that the pole is much longer than the stick. The perception of the magnitude of the object is preserved even if we move further and further away from the object, although the image of the object on the retina will decrease. This phenomenon is called the constant perception of the magnitude of the object.

The perception of the magnitude of the object is determined not only by the size of the image of the object on the retina, but also by the perception of the distance at which we are from the object. This pattern can be expressed as:

Perceived size = Visual angle x Distance.

Accounting for the removal of objects is mainly carried out due to our experience of perception of objects with varying distance to them. A significant support for the perception of the values of objects is knowledge about the approximate size of objects. As soon as we recognize an object, we immediately perceive its value as it really is. In general, it should be noted that the constancy of the value increases significantly when we see familiar objects.

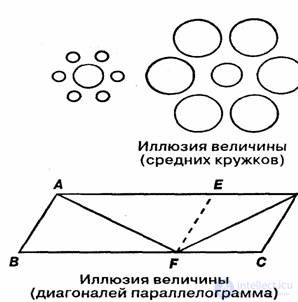

and decreases significantly with the perception of abstract geometric forms. It should also be emphasized that the constancy of perception is preserved only within certain limits. If we are very far from the subject, then it seems to us less than it actually is. For example, when we fly on an airplane, all the items below are very small to us. Another feature of the perception of an object in space is the contrast of objects. The environment in which the object we perceive is located has a noticeable influence on his perception. For example, a person of medium height, surrounded by tall people, seems much smaller than his real height. Another example is the perception of geometric shapes. The circle among large circles seems to be much smaller than the circle of such

Fig. 8.9. The illusion of magnitude with the contrast of objects and the ratio of part and whole. Explanations in the text

|

|

|

Fig. 8.10. Perception of the shape of the subject |

the same diameter, which is among the circles of a much smaller size (Fig. 8.9). Such a distortion of perception caused by the conditions of perception is commonly called an illusion.

The whole in which the object is located can influence the perception of the magnitude of the object. For example, two absolutely equal diagonals of two parallelepipeds are perceived as different in length, if one of them is in the smaller one, and the other in the larger parallelepiped (Fig. 8.9). Here there is an illusion caused by transferring the properties of the whole to its individual parts. Other factors influence the perception of an object in space. For example, the upper parts of the figure appear larger than the lower ones, just as the vertical lines appear longer than the horizontal ones. In addition, the perception of the size of the object is influenced by the color of the object. Light objects appear somewhat larger than dark ones. Volumetric shapes, such as a ball or cylinder, appear smaller than the corresponding flat images.

As complex as the perception of magnitude is the perception of the shape of an object. First of all, it should be noted that when the form is perceived, the phenomenon of constancy is also preserved. For example, when we look at a square or round object located to the side of us, its projection on the retina will look like an ellipse or trapezium. Nevertheless, we always see the same object the same, having the same form. Thus, the perception of the form turns out to be constant and stable, that is, constant. The basis of this constancy is that it takes into account the rotation of the object to us. Moreover, as in the case of the perception of magnitude, the perception of the form largely depends on our experience (Fig. 8.10).

The perception of the shape of an object at a considerable distance may vary. Thus, the small details of the contour disappear as the object is removed, and its shape becomes simplified. The shape as a whole may change. For example, rectangular objects appear rounded. This is because the distance between the sides of the rectangle near its vertices we see in these cases under such a small

From the left point of view, we stop perceiving it, and the tops of the rectangle seem to be drawn inwards, i.e., the corners are rounded.

The process of perception of a volumetric form is very complex . We perceive the volume of the form because human eyes have the ability to binocular view

of The binocular effect is due to the fact that a person looks with two eyes. The essence of the binocular effect is that when both eyes look at the same object, the image of this object on the retina of the left and right "eyes will be different. To make sure of this, take a half-opened book, turn to your back and put it straight in front of you. Then look at it alternately, then left, then right eye. You will notice that it looks differently, which is explained by the displacement of the image of the book on the retina in different directions, while the same points of the book do not These are not on those that are at the same distance and in the same direction from the center of the retina, but on the dispensary points located in each eye at a different distance from the center. With binocular vision, the displacement of images on The retina of the eyes evokes the impression of a single, but voluminous, relief object.

However, binocular vision is not the only condition for volumetric perception of the subject. If we look at the object with one eye, we still perceive its relief. A major role in the perception of the volumetric shape of an object is played by the knowledge of the volume characteristics of a given object, as well as the distribution of light and shadow on a volumetric object.

Human perception of space has a number of features. This is due to the fact that the space is three-dimensional, and therefore for its perception it is necessary to use a number of analyzers working together. At the same time, the perception of space can proceed at different levels.

The perception of three-dimensional space primarily involves the functions of a special vestibular apparatus located in the inner ear. This device has the appearance of three fluid-filled curved semicircular tubes located in the vertical, horizontal and sagittal planes. When a person changes the position of the head, the fluid that fills the channels flows out, irritating the hair cells, and their excitement causes changes in the sense of stability of the body (static sensations).

The vestibular apparatus is closely connected with the occipital muscles, and every change in it causes reflex changes in the position of the eyes. For example, with rapid changes in body position in space, pulsating eye movements, called nystagmus , are observed . There is also feedback. For example, a prolonged rhythmic change of visual stimulation (for example, a long look at a rotating drum with frequent transverse bands) causes a state of instability, accompanied by nausea. The interrelation of the vestibular and oculomotor apparatus, manifested in the optical-vestibular reflexes, is included as one of the most essential components in the perception system of three-dimensional space.

The second apparatus, providing the perception of space, and above all its depth, is the apparatus of binocular vision. The perception of depth is mainly associated with the perception of the distance of objects and their location relative to each other. Binocular vision is one of the conditions for the perception of the distance of objects. For example, if you stretch a thread 3 or 4 meters away from a person and then throw a ball or a ball from above, then, thanks to binocular vision, we can easily see where the ball falls, behind the thread or in front of it. but

|

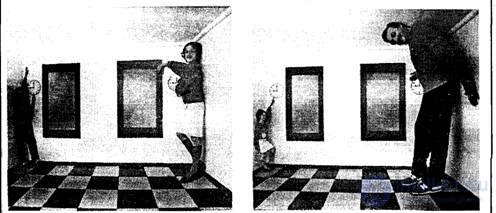

It is interesting What allows a person to adequately perceive the world around us! When studying the characteristics of the perception of various objects, the question arises involuntarily: what makes it easier and what complicates the possibility of adequate perception? One of the factors ensuring the adequacy of perception is the presence of feedback. If not, then the relationship between the signals of the analyzers is not established. Illustrating this fact, R. M. Granovskaya in his book Elements of Practical Psychology cites as an example the sensation of a person who perceives the world around him through special distorting glasses.

|

Fig. 1. Explanations in the text

in monocular vision, the person does not distinguish where the subject falls in relation to the tensioned thread.

A significant role in the perception of the removal of objects, or spatial depth, is played by convergence and divergence of the eyes, because for a clear perception of objects it is necessary that their image falls on the corresponding (corresponding) points of the retina of the left and right eyes, and this is impossible without convergence or divergence of both eyes . Convergence is understood as the reduction of the visual axes of the eyes due to the rotation of the eyeballs towards each other. For example, this occurs when the gaze changes from a distant object to a close one. During the reverse transition, from close to distant object, a di-

|

However, even when wearing such glasses, his undistorted perception of the world can recover. When the subjects who wore such glasses, despite the difficulties, were forced to continue to engage in normal activities - walked the streets, wrote, etc., then at first their actions were extremely unsuccessful. However, gradually they adapted to a distorted perception, and then a moment came when perception was rebuilt and they began to correctly see the world. For example, the well-known psychologist Köhler put himself in the position of a test subject - for four months he wore glasses with wedge-shaped lenses, and within six days he was so restored to the correct coordination of movements that he was able to ski. The factor facilitating the transition to the correct vision in all cases was the apparent presence of gravity. If the subject was given a load suspended from a thread, he adequately perceived the position of this load relative to the thread, despite the fact that other objects could still be turned upside down. Familiarity with an object in the past also accelerated the transition to intelligent vision. For example, a candle that looked upside down until it was burning was perceived correctly as soon as it was lit. It is easy to see that these factors testify to the tremendous importance of feedback in the formation of an adequate image. The role of feedback in the restructuring of perception is convincingly revealed in Kilpatrick's experiments on the perception of spatial relationships in deformed rooms (Fig. 1). These experiments consisted in the demonstration of deformed rooms, designed so that at a certain observer position they were perceived as normal: the configuration that emerged from them on the retina was identical to that obtained from ordinary rooms. Most often the rooms were shown, the walls of which form sharp and obtuse angles. The observer, who was sitting at the observation hole, nevertheless perceived such a room as normal. On the back of her wall, he saw a small and large window. In fact, the windows were of equal size, but due to the fact that one wall was located much closer to the observer than the other, the near window seemed to him more than the far one. If then familiar faces appeared in both windows, the observer was shocked by the inexplicable difference in the size of the faces, the monstrous size of the face in the “far” window. A person can, however, gradually learn to adequately perceive such a distorted room if it serves as the object of his practical activity. So, if he is offered to throw the ball into different parts of the room or is handed a stick with permission to touch it to the walls and corners of the room, then at first he cannot exactly perform the indicated actions: his stick unexpectedly encounters a seemingly far-away wall, then can not touch the near wall, which in a strange way retreats. Gradually, the actions become more and more successful, and at the same time a person acquires the ability to adequately see the actual shape of the room. ” By; Granovskaya R.M. Elements of practical psychology. - SPb .: Light, 1997.

|

vergence of the eyes, i.e., turning them to the sides, dilution of the visual axes. Both convergence and divergence are caused by contraction and relaxation of the eye muscles. Therefore, they are accompanied by certain motor sensations. Although we usually do not notice these sensations, they play a very significant role in the perception of space. So, with the convergence of the eyes, there is a slight disparity of images, a sensation of distance of the object or a stereoscopic effect. When the retinability of the retinal points of both eyes, on which the image falls, is more discontinuity, doubting of the subject occurs. Thus, the impulses due to the relative tension of the eye muscles, which ensure the convergence and displacement of the image on the retina, are

an important source of information for sensory and perceptive areas of the cerebral cortex and the second component of the mechanism of perception of space.

Along with sensations from convergence and divergence of eyes (when looking from a distant object to a close one and back), we get sensations from the accommodation of the eye. The phenomenon of accommodation lies in the fact that the shape of the lens changes as you move and approach objects. This is achieved by contraction or relaxation of the eye muscles, which entails certain sensations of tension or relaxation, which we do not notice, but which are perceived by the corresponding projection fields of the cerebral cortex.

The perception of space is not limited to the perception of depth. In the perception of space plays an important role perception of the location of objects in relation to each other. The fact is that with a considerable distance of the subject, convergence and divergence cease, but the space we perceive is never symmetrical; it is always more or less asymmetrical, that is, objects are located above or below us, to the right or to the left, and also further from us or closer to us. Therefore, it often happens that we judge distance by indirect signs: one object covers another, or the contours of one object are more noticeable than the contours of another.

In addition, it should be noted that the different position of objects in space is often of paramount importance for a person, even more than the perception of the remoteness of an object or the depth of space, because a person does not just perceive space or assess the position of objects, he orients himself in space, and for this he must receive certain information about the location of items. For example, when we need to navigate the location of rooms, save the plan of the path, etc. However, there are situations when a person does not have enough information about the location of things. For example, at the metro station there are two exits. You need to go to a certain street. How will you navigate if there are no auxiliary plates? To ensure orientation in space, additional mechanisms are needed. The notions of “right” and “left” act as such an additional mechanism for a person. With the help of these abstract concepts, a person performs a complex analysis of external space. The formation of these concepts is associated with the selection of the leading hand; for most people, this is the right hand. It is quite natural that at a certain stage of ontogenesis, when the leading right hand is not yet highlighted and the system of spatial concepts is not understood, the sides of space continue to be confused for a long time. These phenomena, characteristic of certain stages of normal development, are manifested in the so-called “mirror letter”, which is observed in many children of three or four years old and drags on if the leading (right) hand for some reason does not stand out.

Such a complex set of mechanisms that ensure the perception of space requires, naturally, an equally complex organization of devices that carry out the central regulation of spatial perception. Such a central apparatus is the tertiary zones of the cerebral cortex, or "overlap zones", which combine the work of the visual, tactile-kinesthetic and vestibular analyzers.

The perception of movement is due to a very complex mechanism, the nature of which has not yet been fully elucidated. What is the complexity of this issue? After all, we can assume that the perception of the movement of objects is due to the movement of the image along the retina of the eye. However, this is not quite true. Imagine that you are walking down the street. Naturally, the images of objects move along your retina, but you do not perceive objects as moving, they are in place (this phenomenon is called constant constancy).

Why do we perceive the movement of material objects? If an object moves in space, then we perceive its movement due to the fact that it leaves the area of the best vision and this causes us to move our eyes or head in order to fix the view on it again. When this occurs, two phenomena. First, the displacement of an object in relation to the position of our body indicates to us its movement in space. Secondly, the brain captures the movement of the eye, watching the subject. The second is especially important for the perception of movement, but the mechanism for processing information about the movement of the eyes is very complex and contradictory. Will a person be able to perceive movement if he is fixed his head and immobilized his eyes? Ernst Mach immobilized the subjects' eyes with a special putty that did not allow the eyes to turn. However, the subject experienced the sensation of moving objects (the illusion of moving objects) each time he tried to turn his eyes. Consequently, it was not the eye movement that was recorded in the brain, but an attempt to move the eyes, i.e., not afferent information about eye movement (a signal about eye movement), but a copy of efferent information (commands for eye movement) is important for perception of movement.

However, the perception of movement cannot be explained only by the movement of the eyes, - we simultaneously perceive movement in two opposite directions.

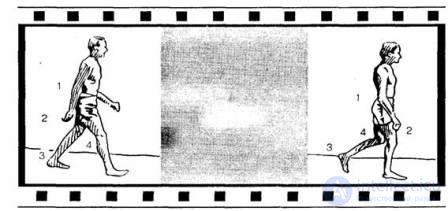

Fig. 8.11. The principle of the stroboscopic effect. Explanations in the text

|

|

Names

Wundt Wilhelm (1832-1920) —German psychologist, physiologist, philosopher, and linguist. He put forward a plan for the development of physiological psychology as a special science, using the method of laboratory experiment to dismember consciousness into elements and clarify the natural relationship between them. In 1879 Wundt founded the world's first experimental psychology laboratory at the University of Leipzig, which has become an international center for research in this field. Sensations, associations, attention, reaction time to various stimuli were studied in this laboratory. Wundt attempted to study higher mental processes, but he, in his opinion, should be carried out using other methods (analysis of myths, rituals, religious beliefs, language), which is reflected in his ten-volume work Psychology of Nations (1900-1920).

Wundt made a significant contribution to the formation of world psychology. Many later well-known psychologists learned from him, including E. Titchener, f. Kruger, G. Munsterberg, Art. Hall, as well as VM Bekhterev and N. N. Lange.

directions, although the eye obviously cannot move simultaneously in opposite directions. At the same time, the impression of movement can occur in the absence of it in reality, for example, if, through short temporary pauses, alternate on the screen a series of images that reproduce the phases of an object’s movement (Fig. 8.11). This is the so-called stroboscopic e4> effect, for the occurrence of which individual stimuli must be separated from each other by certain periods of time. The pause between adjacent stimuli should be at least 0.06 s. In the case when the pause is half as long, the images are merged; в том случае, когда пауза очень велика (например, 1 с), изображения осознаются как раздельные; максимальная пауза, при которой имеет место стробоскопический эффект, равна 0,45 с. Следует отметить, что на стробоскопическом эффекте построено восприятие движения в кинематографе.

В восприятии движения значительную роль, несомненно, играют косвенные признаки, создающие опосредованное впечатление движения. Механизм использования косвенных признаков состоит в том, что при обнаружении неких признаков движения осуществляется их интеллектуальная обработка и выносится суждение том, что предмет движется. Так, впечатление движения может вызвать необычное для неподвижного предмета положение его частей. К числу «кинетических положений», вызывающих представление о движении, принадлежат наклонное положение, меньшая отчетливость очертаний предмета и множество других косвенных признаков. Однако нельзя все же толковать восприятие движения как лежащий за пределами собственно восприятия интеллектуальный процесс:

впечатление движения может возникнуть и тогда, когда мы знаем, что движения на самом деле нет.

All theories of motion perception can be divided into two groups. The first group of theories derives the perception of motion from the elementary, consecutive visual sensations of individual points through which the motion passes, and states that the perception of motion arises from the confluence of these elementary visual sensations (V. Wundt).

Theories of the second group claim that the perception of movement has a specific quality that cannot be reduced to such elementary sensations. Representatives of this theory say that just as, for example, a melody is not a simple sum of sounds, but a qualitatively different whole, so the perception of movement is irreducible to the sum of the elements of this perception of elementary visual sensations. From this position comes, for example, the theory of Gestalt psychology, a famous representative of which is M. Wertheimer.

The perception of movement is, according to Wertheimer, a specific experience, different from the perception of moving objects themselves. If there are two consecutive perceptions of the object in different positions (a) and (b), then the experience of movement does not consist of these two sensations, but connects them, being between them. This experience of the movement Wertheimer calls the fi-phenomenon.

It should be noted that a lot of special work was carried out to study the problem of perception of movement from the position of Gestalt psychology. For example, representatives of this direction put the question to themselves:

What are the conditions when changing spatial relationships in our field of view some of the perceived objects seem to be moving, while others - motionless? In particular, why does it seem to us that the moon is moving, and not clouds? From the standpoint of gestalt psychology, moving objects perceive those objects that are clearly localized on some other object; the figure moves, not the background against which the figure is perceived. Thus, when the moon is fixed against a background of clouds, it is perceived as moving. They showed that of the two objects, usually moving seems to be smaller. The subject that seems to undergo the greatest quantitative or qualitative changes during the experiment also seems to be moving. But research by representatives of Gestalt psychology did not reveal the essence of motion perception. The basic principle governing the perception of motion is the comprehension of the situation in objective reality based on the whole past experience of a person.

The perception of time, despite the importance of this problem, is studied much less than the question of the perception of space. The complexity of studying this issue is that time is not perceived by us as a phenomenon of the material world. We judge him for the course only on certain grounds.

The most elementary forms are the processes of perception of duration and sequence, which are based on elementary rhythmic phenomena known as “biological clocks”. These include rhythmic processes occurring in the neurons of the cortex and subcortical structures. For example, alternating sleep and rest. On the other hand, we perceive time when performing any work, that is, when certain nervous processes occur that ensure our work. Depending on the duration of these processes, alternation of excitation and inhibition, we get certain information about the time. From this we can conclude that in the study of the perception of time it is necessary to take into account two main aspects: the perception of time duration and the perception of time sequence.

Estimation of the duration of the time interval depends largely on what events it was filled with. If there were a lot of events and they were interesting for us, then time passed quickly. Conversely, if there were few events or they were not interesting for us, then time dragged on slowly. However, if you have to evaluate

past events, the estimated duration is the opposite. Time, filled with various events, we overestimate, the time interval seems to us longer. And vice versa, we underestimate the time that is not interesting for us, the time interval seems insignificant to us.

Evaluation of the duration of time depends on emotional experiences. If events cause a positive attitude towards yourself, then time seems to be fast-paced.

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 8 Perception types and properties, physiological mechanisms of perception

Часть 2 8.5. Subject and background in perception - 8 Perception types

Часть 3 test questions - 8 Perception types and properties, physiological mechanisms

Comments

To leave a comment

General psychology

Terms: General psychology