Lecture

General characteristics of volitional action. Will as a process of conscious regulation of behavior. Arbitrary and involuntary movements. Features of voluntary movements and actions. Characteristics of volitional action. The connection of will and feelings.

The basic psychological theory of the will. The problem of the will in the works of ancient philosophers, The problem of the will during the Middle Ages. The concepts of "free will" in the Renaissance, Existentialism - "philosophy of existence ?. IP Pavlov's approach to the consideration of the problem of the will. The interpretation of the will from the position of behaviorism. The concept was introduced in the works of N. A. Bern-Stein. Psychoanalytic concepts of the will.

Physiological and motivational aspects of volitional actions. Physiological basis of the will. Apraxia and Abulia. The role of the second signal system in the formation of volitional actions. The main and side motives of volitional actions. The role of needs, emotions, interests and worldview in the formation of volitional actions.

The structure of volitional action. Components of volitional action. The role of attraction and desires in the formation of motives and goals of activity. Content, purpose and nature of volitional action. Decisiveness and decision making. Types of determination by James. Fighting motives and execution of the decision.

The will qualities of a person and their development. The main qualities of the will. Self-control and self-esteem. The main stages and patterns of formation of volitional actions in a child. The role of conscious discipline in the formation of the will.

Any human activity is always accompanied by specific actions that can be divided into two large groups: voluntary and involuntary. The main difference between arbitrary actions is that they are carried out under the control of consciousness and require from the person a certain effort to achieve a consciously sang. For example, let us imagine a sick person who hardly takes a glass of water in his hand, brings it to his mouth, tilts him, makes his mouth move, that is, performs a whole series of actions united by one goal - to quench his thirst. All individual actions, thanks to the efforts of consciousness aimed at the regulation of behavior, merge into one, and a person drinks water. These efforts are often called volitional regulation, or volition.

Will is the conscious regulation by a person of his behavior and activities, expressed in the ability to overcome internal and external difficulties in committing targeted actions and deeds. The main function of the will is to consciously regulate activity in difficult life conditions. The basis of this regulation is the interaction of the processes of excitation and inhibition of the nervous system. In accordance with this, it is customary to single out the other two, activating and inhibiting, as a concrete definition of the above general 4 ′ function.

Arbitrary or volitional actions develop on the basis of involuntary movements and actions. The simplest of involuntary movements are reflex: narrowing and widening of the pupil, blinking, swallowing, sneezing, etc. This class of movements includes jerking of the hand when touching a hot object, involuntary turning of the head in the direction of the sound, etc. Involuntary nature we usually carry our expressive movements: in case of anger, we involuntarily grit our teeth; with surprise, raise eyebrows or open mouth; when we rejoice at something, we start smiling, etc.

Behavior, like action, can be involuntary or arbitrary. The involuntary type of behavior mainly includes impulsive actions and unconscious, not subordinate to the common goal of the reaction, such as noise outside the window, an object that can satisfy the need, etc. The human behavioral reactions observed in affect situations when a person is under the influence of an uncontrolled emotional state of consciousness.

In contrast to involuntary actions, conscious actions that are more characteristic of human behavior are aimed at achieving the set goal. It is the consciousness of action that characterizes volitional behavior. However, volitional actions may include as separate links such movements that were automated during the formation of a skill and lost their initially conscious character.

Volitional actions differ from each other primarily in their level of complexity. There are very complex volitional actions, which include a number of simpler ones. So, the above example, when a person wants to quench their thirst, gets up, pours water into a glass, etc., is an example of complex volitional behavior, which includes some less complex volitional actions. But there are even more complex volitional actions. For example, climbers who decide to conquer a mountain peak begin their training long before climbing. This includes training, equipment inspection, fitting fixtures, route selection, etc. But the main difficulties await them ahead when they begin their ascent.

The basis for the complication of action is the fact that not every goal that we set can be achieved immediately. Most often, achieving the goal requires the implementation of a series of intermediate actions that bring us closer to the goal.

Another important sign of volitional behavior is its connection with overcoming obstacles, no matter what type of obstacles - internal or external. Internal, or subjective, obstacles are the motivations of a person, aimed at the non-fulfillment of a given action or at the performance of opposing actions. For example, a schoolboy wants to play with toys, but at the same time he needs to do his homework. Fatigue, the desire to have fun, inertia, laziness, etc. can serve as internal obstacles. For example, the lack of a necessary tool for work or opposition from other people who do not want the goal to be achieved can serve as an example of external obstacles.

It should be noted that not every action aimed at overcoming an obstacle is volitional. For example, a person running away from a dog can overcome very difficult obstacles and even climb a tall tree, but these actions are not strong-willed, because they are caused primarily by external causes, and not by the internal attitudes of a person. Thus, the most important feature of volitional actions aimed at overcoming obstacles is the consciousness of the significance of the goal for which it is necessary to fight, the consciousness of the need to achieve it. The more meaningful the goal is for a person, the more obstacles it overcomes. Therefore, volitional actions can differ not only in the degree of their complexity, but also in the degree of awareness.

Usually, we are more or less clearly aware of the reason for which we perform certain actions, we know the goal, which we strive to achieve. There are cases when a person is aware of what he is doing, but cannot explain why he is doing it. Most often this happens when a person is gripped by some strong feelings, experiences emotional excitement. Such actions are called impulsive. The degree of awareness of such actions is greatly reduced. Having committed rash actions, a person often repents for what he has done. But the will is precisely in the fact that a person is able to restrain himself from committing rash acts during affective outbursts. Consequently, the will is associated with mental activity and feelings.

Will implies the existence of a person’s purposefulness, which requires certain thought processes. The manifestation of thinking is expressed in the conscious choice of the goal and the selection of means for its achievement. Thinking is also necessary during the execution of the conceived action. Carrying out the planned action, we face many difficulties. For example, the conditions for performing an action may change, or it may be necessary to change the means to achieve a goal. Therefore, in order to achieve the goal, a person must constantly compare the goals of the action, the conditions and means of its implementation and make the necessary adjustments in a timely manner. Without the participation of thinking, volitional actions would be deprived of consciousness, that is, they would cease to be volitional actions.

The connection of will and feelings is expressed in the fact that, as a rule, we pay attention to objects and phenomena that cause certain feelings in us. The desire to achieve or achieve something, just like avoiding something unpleasant, is connected with our feelings. What is indifferent for us, not causing any emotions, as a rule, does not act as the goal of action. However, it is a mistake to assume that only feelings are sources of volitional action. Often we are faced with a situation where feelings, on the contrary, act as an obstacle to the achievement of a goal. Therefore, we have to make volitional efforts to counter the negative effects of emotions. Convincing evidence that feelings are not the only source of our actions, are pathological cases of loss of the ability to experience feelings while retaining the ability to consciously act. Thus, the sources of volitional actions are very diverse. Before proceeding to their consideration, we need to get acquainted with the basic and most well-known theories of the will and how they reveal the causes of volitional actions in humans.

Understanding the will as a real factor of behavior has its own history. At the same time, in the views on the nature of this mental phenomenon, two aspects can be distinguished: philosophical-ethical and natural-science. They are closely intertwined and can be considered only in interaction with each other.

At the time of antiquity and the Middle Ages, the problem of the will was not considered from the positions characteristic of its modern understanding. Ancient philosophers considered purposeful or conscious behavior of a person only from the position of its conformity with generally accepted norms. In the ancient world, the ideal of the sage was first recognized, therefore, the ancient philosophers believed that the rules of human behavior should correspond to the rational principles of nature and life, the rules of logic. So, according to Aristotle, the nature of the will is expressed in the formation of a logical conclusion. For example, in his “Nicomachean ethics” the premise “all sweet should be eaten” and the condition “these apples are sweet” entail not a prescription “this apple should be eaten”, but the conclusion about the need for a specific action - eating an apple. Therefore, the source of our conscious actions lies in the mind of man.

It should be noted that such views on the nature of the will are quite reasonable and therefore continue to exist today. For example, Sh. N. Chkhartishvili opposes the special nature of the will, considering that the concepts of goal and awareness are categories of intellectual behavior, and there is no need to introduce new terms, in his opinion. This view is justified by the fact that thought processes are an integral component of volitional actions.

In fact, the problem of the will did not exist as an independent problem even during the Middle Ages. Man was considered by medieval philosophers as an exclusively passive principle, as a “field” on which external forces meet. Moreover, very often in the Middle Ages, the will was endowed with an independent existence and was even personified in specific forces, turning into good or evil creatures. However, in this interpretation, the will acted as a manifestation of a certain mind that sets itself certain goals. The knowledge of these forces, good or evil, in the opinion of medieval philosophers, opens the way to the knowledge of the "true" reasons for the actions of a particular person.

Consequently, the concept of will during the Middle Ages was largely associated with certain higher powers. Such an understanding of the will in the Middle Ages was due to the fact that society denied the possibility of an independent, that is, independent of the traditions and the established order, the behavior of a particular member of society. The person was considered as the simplest element of society, and the set of characteristics that modern scientists put into the concept of “personality”, acted as a program according to which the ancestors lived and according to which a person should live. The right to deviate from these norms was recognized only for some members of the community, for example, a blacksmith - a man who is subject to the power of fire and metal, or behind a robber - a human criminal who opposed himself to this society, etc.

It is likely that the independent problem of will arose simultaneously with the formulation of the problem of personality. This happened in the Renaissance, when a man began to recognize the right to work and even to make a mistake. The opinion began to prevail that only by deviating from the norm, having stood out from the general mass of people, could a person become a person. In this case, the main value of the individual was considered to be free will.

In terms of historical facts, we should note that the emergence of the problem of free will was not accidental. The first Christians proceeded from the fact that a person has free will, that is, he can act in accordance with his conscience, can make a choice in how he should live, act and what rules to follow. In the era of the Renaissance, free will in general began to be elevated to the rank of absolute.

Subsequently, the absolutization of free will led to the emergence of the worldview of existentialism - the “philosophy of existence”. Existentialism (M. Heidegger, K. Jaspers, J.P. Sartre, A. Camus, and others) regards freedom as an absolutely free will. not caused by any external social circumstances. The starting point of this concept is an abstract person, to take it outside of public relations and relations, outside the socio-cultural environment. A person, in the opinion of representatives of this trend, can not be connected with society in any way, and, moreover, he cannot be bound by any moral obligations or responsibilities. Man is free and can not answer for anything. Any rule appears to him as the suppression of his free will. According to J.P. Sartre, only spontaneous unmotivated protest against any “sociality” can be genuinely human, and it is not organized in any way, not bound by any framework of organizations, programs, parties, etc.

Such an interpretation of the will contradicts modern ideas about man. As we noted in the first chapters, the main difference between a person as a representative of the species Homo deer and the animal world lies in its social nature. A human being, developing outside of human society, has only an external resemblance to a person, and in its mental essence has nothing to do with people.

Absolutization of free will led representatives of existentialism to the erroneous interpretation of human nature. Their mistake was to misunderstand that a person who commits a certain act, aimed at rejecting any existing social norms and values, certainly affirms other norms and values. Indeed, in order to reject something, it is necessary to have a certain alternative, otherwise such denial turns into absurdity at best, and madness at worst.

One of the first natural-science interpretations of the will belongs to IP Pavlov, who considered it as the “instinct of freedom”, as a manifestation of the activity of a living organism when it encounters obstacles that limit this activity. According to I.P. Pavlov, the will as the “instinct of freedom” is no less a stimulus of behavior than the instincts of hunger and danger. “Do not be him,” he wrote, “every slightest obstacle that an animal would meet on its way would completely interrupt the course of its life” (I. P. Pavlov,

|

|

Names

Kornilov Konstantin Nikolaevich (1879-1957) - a domestic psychologist. He began his scientific career as an employee of G. I. Chelpanov. For several years he worked at the Institute of Psychology, created by Chelpanov. In 1921 wrote the book "Teaching about human reactions." In 1923-1924 began active work on the creation of materialistic psychology. The central place in his views was the position of the psyche as a special property of highly organized matter. This work ended with the creation of the concept of reactology, which, as a Marxist psychology, Kornilov tried to oppose, on the one hand, Bechterew's reflexology, and on the other, introspective psychology. Основным положением этой концепции явилось положение о «реакции», которая рассматривалась как первоэлемент жизнедеятельности, сходный с рефлексом и вместе с тем отличающийся от него наличием «психической стороны». В результате проводимой в 1931 г . так называемой «реактологической дискуссии» Корнилов отказался от своих взглядов. Впоследствии изучал проблемы воли и характера. Возглавлял Московский институт психологии.

1952). Для человеческого же поступка такой преградой может быть не только внешнее препятствие, ограничивающее двигательную активность, но и содержание его собственного сознания, его интересы и т. д. Таким образом, воля в трактовке И. П. Павлова рефлекторна по своей природе, т. е. она проявляется в виде ответной реакции на воздействующий стимул. Поэтому не случайно данная трактовка нашла самое широкое распространение среди представителей бихевиоризма и получила поддержку в реактологии (К. Н. Корнилов) и рефлексологии (В. М. Бехтерев). Между тем если принять данную трактовку воли за истинную, то мы должны сделать вывод о том, что воля человека зависит от внешних условий, а следовательно, волевой акт не в полной мере зависит от человека.

В последние десятилетия набирает силу и находит все большее число сторонников другая концепция, согласно которой поведение человека понимается как изначально активное, а сам человек рассматривается как наделенный способностью к сознательному выбору формы поведения. Эта точка зрения удачно подкрепляется исследованиями в области физиологии, проведенными Н. А. Бернштейном и П. К. Анохиным. Согласно сформировавшейся на основе этих исследований концепции, воля понимается как сознательное регулирование человеком своего поведения. Это регулирование выражено в умении видеть и преодолевать внутренние и внешние препятствия.

Помимо указанных точек зрения существуют и другие концепции воли. Так, в рамках психоаналитической концепции на всех этапах ее эволюции от 3. Фрейда до Э. Фромма неоднократно предпринимались попытки конкретизировать представление о воле как своеобразной энергии человеческих поступков. Для представителей данного направления источником поступков людей является некая превращенная в психическую форму биологическая энергия живого организма. Сам Фрейд полагал, что это психосексуальная энергия полового влечения.

Весьма интересна эволюция этих представлений в концепциях учеников и последователей Фрейда. Например, К. Лоренц видит энергию воли в изначальной

агрессивности человека. Если эта агрессивность не реализуется в разрешаемых и санкционируемых обществом формах активности, то становится социально опасной, поскольку может вылиться в немотивируемые преступные действия. А. Адлер, К. Г. Юнг, К. Хорни, Э. Фромм связывают проявление воли с социальными факторами. Для Юнга — это универсальные архетипы поведения и мышления, заложенные в каждой культуре, для Адлера — стремление к власти и социальному господству, а для Хорни и Фромма — стремление личности к самореализации в культуре.

По сути дела, различные концепции психоанализа представляют собой абсолютизацию отдельных, хотя и существенных, потребностей как источников человеческих действий. Возражения вызывают не столько сами преувеличения, сколько общая трактовка движущих сил, направленных, по мнению приверженцев психоанализа, на самосохранение и поддержание целостности человеческого индивида. На практике очень часто проявление воли связано со способностью противостоять потребности самосохранения и поддержания целостности человеческого организма. Это подтверждает героическое поведение людей в экстремальных условиях с реальной угрозой для жизни.

В действительности мотивы волевых действий складываются и возникают в результате активного взаимодействия человека с внешним миром, и в первую очередь с обществом. Свобода воли означает не отрицание всеобщих законов природы и общества, а предполагает познание их и выбор адекватного поведения.

Волевые действия, как и все психические явления, связаны с деятельностью мозга и наряду с другими сторонами психики имеют материальную основу к ниде нервных процессов.

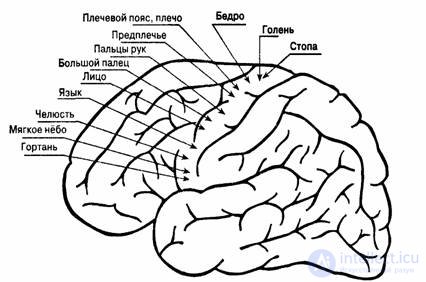

Материальной основой произвольных движений является деятельность так называемых гигантских пирамидных клеток, расположенных в одном из слоен коры мозга в области передней центральной извилины и по своим размерам во много раз превышающих окружающие их другие нервные клетки. Эти клетки очень часто называют «клетками Беца» по имени профессора анатомии Киевского университета В. А. Беца, который впервые описал их в 1874 г . В них зарождаются импульсы к движению, и отсюда берут начало волокна, образующие массивный пучок, который идет в глубину мозга, спускается вниз, проходит внутри спинного мозга и достигает в конечном итоге мышцы противоположной стороны тела (пирамидный путь).

Все пирамидные клетки условно, в зависимости от их местоположения и выполняемых функций, можно разделить на три группы (рис. 15.1). Так, в верхних отделах передней центральной извилины лежат клетки, посылающие импульсы к нижним конечностям, в средних отделах лежат клетки, посылающие импульсы к руке, а в нижних отделах располагаются клетки, активизирующие мышцы языка,

380 • Часть II. Психические процессы

Fig. 15.1. Двигательные центры коры головного мозга у человека (по Гринштейну)

губ, гортани. Все эти клетки и нервные пути являются двигательным аппаратом коры головного мозга. В случае поражения тех или иных пирамидных клеток у человека наступает паралич соответствующих им органов движения.

Произвольные движения выполняются не изолированно друг от друга, а в сложной системе целенаправленного действия. Это происходит благодаря определенной организации взаимодействия отдельных участков мозга. Большую роль здесь играют участки мозга, которые хотя и не являются двигательными отделами, но обеспечивают организацию двигательной (или кинестетической) чувствительности, необходимую для регуляции движений. Эти участки располагаются сзади от передней центральной извилины. В случае их поражения человек перестает ощущать собственные движения и поэтому не в состоянии совершать даже относительно несложные действия, например взять какой-либо предмет, находящийся возле него. Затруднения, возникающие в этих случаях, характеризуются тем, что человек подбирает не те движения, которые ему нужны.

Сам по себе подбор движений еще не достаточен для того, чтобы действие было выполнено умело. Необходимо обеспечить преемственность отдельных фаз движения. Такая плавность движений обеспечивается деятельностью премоторной зоны коры, которая лежит кпереди от передней центральной извилины. При поражении этой части коры у больного не наблюдается никаких параличей (как при поражении передней центральной извилины) и не возникает никаких затруднений в подборе движений (как при поражении участков коры, расположенных сзади от передней центральной извилины), но при этом отмечается значительная неловкость. Человек перестает владеть движениями так, как он владел ими ранее. Более того, он перестает владеть приобретенным навыком, а выработка сложных двигательных навыков в этих случаях оказывается невозможной.

В некоторых случаях, когда поражение этой части коры распространено в глубь мозгового вещества, наблюдается следующее явление: выполнив какое-либо движение, человек никак не может его прекратить и продолжает в течение некоторого

|

From the history of psychology Патология воли чаще всего выражается в нарушении регуляции поведения человека. Это может проявляться или в нарушении критичности, или в спонтанности поведения. В качестве иллюстрации приведем несколько описаний подобных больных из книги Б. В. Зейгарник «Патопсихология». «...Поведение этих больных обнаруживало патологические особенности. Адекватность их поведения была кажущейся. Так, они помогали сестрам, санитарам, если те их просили, но они с той же готовностью выполняли любую просьбу, даже если она шла вразрез с принятыми нормами поведения. Так, больной К. взял без разрешения у другого больного папиросы, деньги, так как кто-то "его попросил сделать это"; другой больной Ч., строго подчинявшийся режиму госпиталя, "хотел накануне операции выкупаться в холодном озере, потому что кто-то сказал, что вода теплая". Иными словами, их поведение, действия могли в одинаковой мере оказаться адекватными и неадекватными, ибо они были продиктованы не внутренними потребностями, а чисто ситуационными моментами. Точно так же отсутствие жалоб у них обусловливалось не сдержанностью, не желанием замаскировать свой дефект, а тем, что они не отдавали себе отчета ни в своих переживаниях, ни в соматических ощущениях. Эти больные не строили никаких планов на будущее: они с одинаковой готовностью соглашались как с тем, что не в состоянии работать по прежней профессии, так и с тем, что могут успешно продолжать прежнюю деятельность. Больные редко писали письма своим родным, близким, не огорчались, не волновались, когда не получали писем. Отсутствие чувства горести или радости часто выступало в историях болезни при описании психического статуса подобных больных. Чувство заботы о семье, возможность планирования своих действий были им чужды. Они выполняли работу добросовестно, но с таким же успехом могли бросить ее в любую минуту. После выписки из госпиталя такой больной мог с одинаковым успехом поехать домой или к товарищу, который случайно позвал его. Действия больных не были продиктованы ни внутренними мотивами, ни их потребностями. Отношение больных к окружающему было глубоко изменено. Это измененное отношение особенно отчетливо выступает, если проанализировать не отдельные поступки больного, а его поведение в трудовой ситуации. Трудовая деятельность направлена на достижение продукта деятельности и определяется отношением человека к этой деятельности и ее продукту. Следовательно, наличие такого отношения к конечному результату заставляет человека предусматривать те или иные частности, детали, сопоставлять отдельные звенья своей работы, вносить коррекции. Трудовая деятельность включает в себя планирование задания, контроль своих действий, она является прежде всего целенаправленной и сознательной. Поэтому распад действия аспонтанных больных, лишенных именно этого отношения, легче всего проявляется в трудовой ситуации обучения.

|

time to perform it many times in a row. So, going to write the number "2" and making the movement necessary to write the upper circle of the number, a person with a similar defeat continues the same movement and, instead of completing the writing of the number, writes a large number of circles.

In addition to these areas of the brain should be noted structures that direct and maintain the focus of volitional action. Every volitional action is determined by certain motives that must be retained throughout the execution of the movement or action. If this condition is not met, then the movement (action) performed will be interrupted or replaced by others. An important role in maintaining the goal of action is played by brain regions located in the frontal lobes. These are the so-called prefrontal areas of the cortex, which were the last to form during the evolution of the brain. With their defeat apraxia occurs , manifested in the violation of arbitrary regulation

|

external reasons, for example in case of tool breakage, prohibition of personnel, etc. The fact that they almost did not regulate their efforts, but worked with the maximum available intensity and pace, despite expediency, drew attention. For example, patient A. was instructed to trim the board. He planed it quickly, pressing the planer excessively, did not notice how he struck the whole plane, and continued to plan the workbench. Patient K. was taught to sweep over the loops, but he hurriedly, fussily, pulled the needle with the thread, without checking the correctness of the puncture made, that the loops were ugly and wrong. He could not work slower, no matter how he was asked about it. Meanwhile, if the instructor was sitting next to the patient and literally at every stitch "shouted" at the patient; "Take your time! Check!" - the patient could make the loop beautiful and even, he understood how to do it, but he could not help it hurry. Performing the simplest task, the patients always made a lot of unnecessary fussy movements. They, as a rule, worked according to the "trial and error" method. If the instructor asked what they were supposed to do, then very often he managed to get the right answer. Being, however, presented to themselves, patients rarely used their thought as an instrument of foresight. This indifferent attitude towards their activities was revealed in the process of experimental learning. For 14 days, systematic training was conducted with these patients: memorization of the poem, folding mosaics on the proposed pattern and button sorting. A group of patients with massive lesions of the left frontal lobe was isolated, in whom the clinic and psychological research revealed a rough syndrome of spontaneity. The patients were able to mechanically learn the poem, they could easily lay out figures from the mosaic, but could not plan rational techniques or modify the proposed them from the outside to consolidate or speed up the work. So, laying out a mosaic without a plan, they did not assimilate and did not tolerate the methods offered to them from the outside and repeated the same mistakes the next day; they could not master the training system that planned their activities. They were not interested in acquiring new learning skills, were completely indifferent to him, they were indifferent to the final results. Therefore, they could not develop new skills: they had old skills, but it was difficult for them to master new ones. Passive, aspontanny behavior was often replaced in these patients with increased response to random stimuli. Despite the fact that this kind of patient lies without any movement, without being interested in others, he answers the doctor's question extremely quickly; for all his passivity, he often reacts when the doctor talks with a neighbor in the ward, interferes with the conversations of others, becomes annoying. In reality, this “activity” is not caused by internal impulses. Such behavior should be interpreted as situational. "

By: Zeygarnik B.V. Pathopsychology. - M .: Publishing House, 1986 |

movements and actions. A person with such a brain damage, starting to perform any action, immediately stops or changes it as a result of any accidental impact, which makes it impossible to perform an act of will. In clinical practice, a case was described where such a patient, passing by an open cabinet, entered it and began to look around around helplessly, not knowing what to do next: one type of open door of the cabinet turned out to be sufficient for him to change his original intention and enter cupboard. The behavior of such patients turns into uncontrollable, broken actions.

On the basis of cerebral pathology, Abulia may also appear , manifested in the absence of impulses to act, in the inability to make a decision and take the necessary action, although the need is recognized. Abulia is caused by pathological inhibition of the cortex, as a result of which the intensity of the impulses to action turns out to be significantly below the optimal level. By sw

To T. Ribot, one patient on recovery said so about his condition: "The lack of activity was due to the fact that all my feelings were unusually weak, so that they could not exert any influence on my will."

It should be noted that the second signal system, which implements the entire conscious regulation of human behavior, is of particular importance in the execution of volitional actions. The second signaling system activates not only the motor part of human behavior, it is a trigger signal for thinking, imagination, memory; it also regulates attention, evokes feelings and thus affects the formation of the motives of volitional actions.

Since we approached the consideration of the motives of volitional actions, it is necessary to distinguish between the motives and the volitional action itself. Under the motives of volitional actions are those reasons that encourage a person to act. All motives of volitional actions can be divided into two main groups: main and side. Moreover, speaking of two groups of motives, we cannot list the motives included in the first or second group, because in different conditions of activity or in different people the same motive (motive reason) may be in one case basic, and in the other - side. For example, for one person, the desire for knowledge is the main motive of writing a dissertation, and the achievement of a certain social status is secondary. At the same time, for another person, on the contrary, the achievement of a certain social status is the main motive, and cognition is by-product.

The basis of the motives of volitional actions are the needs, emotions and feelings, interests and inclinations, and especially our worldview, our views, beliefs and ideals that are formed in the process of educating a person.

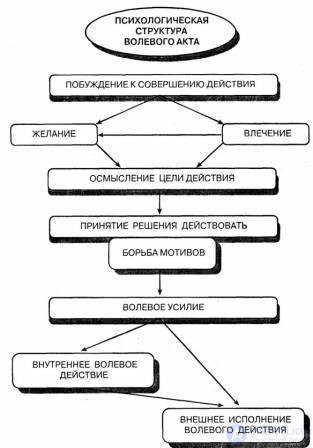

What begins volitional action? Of course, from the awareness of the purpose of the action and the motive associated with it. With a clear awareness of the goal and the motive that causes it, the desire for the goal is called desire (Fig. 15.2).

But not all striving for a goal is quite deliberate. Depending on the degree of awareness of their needs, they are divided into inclinations and desires. If the desire is conscious, then the attraction is always vague, it is not clear: the person realizes that he wants something, lacks something or needs something, but what exactly he does not understand. Usually people experience attraction as a specific painful condition in the form of anguish or uncertainty. Because of its ambiguity, the impulse cannot develop into purposeful activity. Therefore, attraction is often viewed as a transitional state. The need presented in it, as a rule, either dies away, or is realized and transformed into a concrete desire.

It should be noted that not every desire leads to action. Desire itself will not hold the active element. Before a desire becomes a direct motive, and then a goal, it is evaluated by a person, i.e.

Fig. 15.2. Psychological structure of volition

“Filtered” through the value system of a person, receives a certain emotional coloring. Everything connected with the realization of a goal is painted in positive colors in the emotional sphere, as well as everything that is an obstacle to achieving a goal causes negative emotions.

Having a motivating force, the desire sharpens the awareness of the goal of the future action and the construction of its plan. In turn, when forming a goal, its content, character and value play a special role . The greater the goal, the more powerful the aspiration may be caused by it.

Desire is not always immediately realized. A person sometimes has several unmatched and even contradictory desires at once, and he finds himself in a very difficult situation, not knowing which of them to realize. The mental state, which is characterized by the collision of several desires or several different motivations for activity, is usually called the struggle of motives. The struggle of motives includes the evaluation by a person of those reasons which speak for and against the need to act in a certain direction, considering how to act. The final moment of the struggle of motives is the decision to choose the purpose and method of action. Making a decision, a person shows determination; however, he usually feels responsible for the further course of events. Considering the decision-making process, U. Jame distinguished several types of decisiveness.

1. Reasonable determination manifests itself when opposing motives begin to fade, leaving room for an alternative that is perceived quite calmly. The transition from doubt to confidence is experienced passively. It seems to a person that the grounds for action are formed by themselves in accordance with the conditions of activity.

2. In cases where collusion and indecision are too prolonged, a moment may come when a person is more likely to make the wrong decision than not to take any. Moreover, some random circumstance often breaks the balance, giving one of the prospects an advantage over the others, and the person seems to be subordinate to fate.

3. In the absence of motive reasons, wanting to avoid the unpleasant sensation of indecision, a person begins to act as if automatically, simply striving to move forward. What will happen next does not concern him at the moment. As a rule, this type of decisiveness is characteristic of persons with an intense desire for activity.

4. The following type of decisiveness includes cases of moral rebirth, the awakening of conscience, etc. In this case, the cessation of internal fluctuations occurs due to a change in the scale of values. In humans, an internal fracture takes place, and immediately there is a determination to act in a particular direction.

5. In some cases, a person who does not have rational grounds considers a certain course of action more preferable. With the help of the will, he strengthens the motive, which by itself could not subjugate the others. Unlike the first case, the function of the mind here is performed by the will.

It should be noted that in psychological science there is an active debate on the problem of decision making. On the one hand, the struggle of motives and the subsequent decision-making are considered as the main link, the core of a volitional act. On the other hand, there is a tendency to turn off from the volitional act of the inner workings of consciousness associated with choice, reflection and evaluation.

There is another point of view characteristic of those psychologists who, without rejecting the significance of the struggle of motives and the inner workings of consciousness, see the essence of will in the execution of the decision, because the struggle of motives and the decision following this do not go further than subjective states. It is the execution of the decision that constitutes the main point of volitional human activity.

The executive phase of volitional action has a complex structure. First of all, the execution of the decision made is associated with one or another time, i.e., with a certain period. If the execution of the decision is postponed for a long time, then in this case it is customary to talk about the intention to execute the decision made. We usually talk about intent when faced with complex activities: for example, to enter a university, get a certain specialty. The simplest volitional actions, such as quenching thirst or hunger, change the direction of their movement, so as not to collide with a person coming towards them, are executed, as a rule, immediately. Intention is inherently an internal preparation of a deferred action and is an orientation fixed by the decision towards the realization of a goal. However, intention alone is not enough. As in any other volitional action, with the existence of intention, we can distinguish the planning stage of ways to achieve the goal. The plan can be detailed to varying degrees. For some people, there is a characteristic desire to foresee everything, to plan each step. At the same time, others are content with only a general scheme. In this case, the planned action is not implemented immediately. To implement it requires a conscious will effort. By volitional effort is meant a particular state of internal tension, or activity, which causes the mobilization of a person’s internal resources necessary to perform the intended action. Therefore, volitional efforts are always associated with a considerable waste of energy.

This final stage of volitional action can get a double expression: in some cases it manifests itself in an external action, in other cases, on the contrary, it consists in refraining from any external action (this manifestation is usually called an internal volitional action).

Volitional effort is qualitatively different from muscle tension. In a volitional effort, external movements can be represented minimally, and internal stress can be quite significant. At the same time, muscular tension is present in varying degrees in any volitional effort. For example, considering or remembering something, we strain the muscles of the forehead, eyes, etc., but this does not give reason to identify the muscular and volitional efforts.

In various specific conditions, the willpower we show will vary in intensity. This is due to the fact that the intensity of volitional efforts primarily depends on both external and internal obstacles encountered in the implementation of volitional actions. However, besides the situational

|

|

Names

Jema William (1842-1910) is an American psychologist and philosopher, one of the founders of modern American functionalism. He offered one of the first in psychology, the theory of personality. In the "empirical self," or personality, they identified: 1. physical personality, which includes our own body organization, home, family, state, etc. 2. Social personality as a form of recognition of our personality in other people. 3. The spiritual person as the unity of all spiritual properties and states of the person - thinking, emotions, desires, etc., with the center in the sense of activity “I”.

Jeme viewed consciousness, understood as a stream of consciousness, in the context of its adaptive functions. At the same time, special importance was attached to the activity and selectivity of consciousness.

Jamé is also the author of the theory of emotions, known as the James – Lange theory. According to this theory, the emotional states experienced by the subject (fear, joy, etc.) represent the effect of physiological changes in the muscular and vascular systems. He had a significant impact on the research of many psychologists at the beginning of the 20th century.

factors, there are also relatively stable factors that determine the intensity of volitional efforts. These include the following: the worldview of the individual, manifested in relation to certain phenomena of the surrounding world; moral stability, which determines the ability to follow the intended path; the level of self-management and self-organization of the personality, etc. All these factors are formed in the process of human development, its formation as a personality and characterize the level of development of the volitional sphere.

A person's will is characterized by certain qualities. First of all, it is customary to allocate willpower as a generalized ability to overcome significant difficulties that arise on the way to achieving the goal. The more serious the obstacle that you have overcome on your way to your goal, the stronger your will. It is the obstacles overcome by volitional efforts that are an objective indicator of the manifestation of willpower.

Среди различных проявлений силы воли принято выделять такие личностные черты, как выдержка и самообладание, которые выражаются в умении сдерживать свои чувства, когда это требуется, в недопущении импульсивных и необдуманных действий, в умении владеть собой и заставлять себя выполнять задуманное действие, а также воздерживаться от того, что хочется делать, но что представляется неразумным или неправильным.

Другой характеристикой воли является целеустремленность. Под целеустремленностью принято понимать сознательную и активную направленность личности на достижение определенного результата деятельности. Очень часто, когда

говорят о целеустремленности, используют такое понятие, как настойчивость. Это понятие практически тождественно понятию целеустремленности и характеризует стремление человека в достижении поставленной цели даже в самых сложных условиях. Обычно различают целеустремленность стратегическую, т. е. умение руководствоваться во всей своей жизнедеятельности определенными принципами и идеалами, и целеустремленность оперативную, заключающуюся в умении ставить ясные цели для отдельных действий и не отклоняться от них в процессе их достижения.

От настойчивости принято отличать упрямство. Упрямство чаще всего выступает как отрицательное качество человека. Упрямый человек всегда старается настоять на своем, несмотря на нецелесообразность данного действия. Как правило, упрямый человек в своей деятельности руководствуется не доводами разума, а личными желаниями, вопреки их несостоятельности. По сути, упрямый человек не владеет своей волей, поскольку он не умеет управлять собой и своими желаниями.

Важной характеристикой воли является инициативность. Инициативность заключается в способности предпринимать попытки к реализации возникших у человека идей. Для многих людей преодоление собственной инертности является наиболее трудным моментом волевого акта. Сделать первый осознанный

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 15. Mental Processes

Часть 2 Патология воли. - 15. Mental Processes

Comments

To leave a comment

General psychology

Terms: General psychology