In the previous parts, we described a model of a neural network, which we called wave. Our model is significantly different from traditional wave models. It is usually assumed that each neuron has its own oscillations. The joint work of such neurons prone to systematic pulsation leads in classical models to a certain general synchronization and the emergence of global rhythms. We put a completely different meaning into the wave activity of the cortex. We have shown that neurons are able to record information not only due to changes in the sensitivity of their synapses, but also due to changes in membrane receptors located outside the synapses. As a result, the neuron acquires the ability to respond to a large set of specific patterns of activity of the surrounding neurons. We have shown that the triggering of several neurons forming a certain pattern necessarily triggers a wave propagating through the cortex. Such a wave is not just a disturbance transmitted from a neuron to a neuron, but a signal that creates a certain pattern of neuron activity that is unique for each pattern that radiates as it progresses. This means that in any place of the cortex, according to the pattern that the wave brought with it, it is possible to determine which patterns on the cortex came into activity. We have shown that through small bundles of fibers, wave signals can be projected onto other areas of the cortex. Now we will talk about how synaptic training of neurons can occur in our wave networks.

Isolation of wave factors

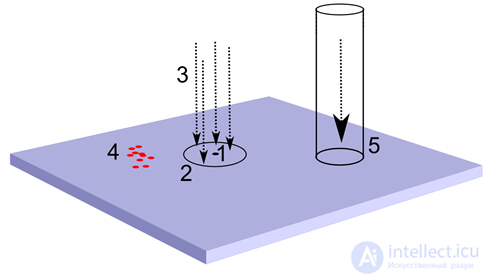

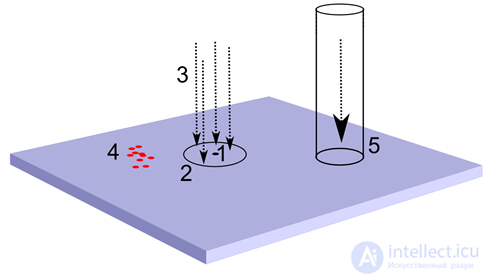

Take an arbitrary neuron of the cortex (picture below). He has a receptive field within which he has a dense network of synaptic connections. These compounds encompass both the surrounding neurons and axons entering the cortex, carrying signals from other parts of the brain. Due to this, the neuron is able to monitor the activity of a small area surrounding it. If a zone of the cortex to which it belongs, has a topographic projection, then the neuron receives signals from those axons that fall into its receptive field. If there are active patterns of evoked activity on the cortex, then the neuron sees fragments of identification waves from them when they pass by it. Similarly, with waves that arise from wave tunnels that carry the wave pattern from one region of the brain to another.

Sources of information to highlight the factor. 1 — cortex neuron, 2 — receptive field, 3 — topographic projection, 4 — induced activity pattern, 5 — wave tunnel

Sources of information to highlight the factor. 1 — cortex neuron, 2 — receptive field, 3 — topographic projection, 4 — induced activity pattern, 5 — wave tunnel

In the activity seen by the neuron at its receptive field, regardless of its origin, the main principle is observed - each unique phenomenon causes its own unique pattern inherent only in this phenomenon. The phenomenon repeats - the activity pattern that is visible to the neuron repeats.

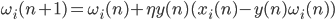

If what is happening contains several phenomena, then several patterns are superimposed on each other. When overlapping, the activity patterns may not coincide in time, that is, the wave fronts may miss each other. To take this into account, we choose an exponential time interval equal to the period of one wave cycle. For each synaptic input of a neuron, we will accumulate activity during this period of time. That is, just sum up how many spikes came to a particular input. As a result, we obtain an input vector describing the pattern of synaptic activity integrated over the cycle. Having such an input vector, we can use all the previously described learning methods for a neuron. For example, we can turn a neuron into a Hebb filter and make it select the main component contained in the input data stream. In its meaning it will be the identification of those inputs on which the incoming signals most often manifested themselves together. With reference to the identification waves, this means that the neuron will determine which waves have a pattern to appear from time to time together, and will adjust its weights to recognize this combination. That is, having selected such a factor, the neuron will begin to show induced activity when it recognizes the familiar combination of identifiers.

Thus, a neuron will acquire the properties of a neuron detector that is tuned to a specific phenomenon, which is detected by its characteristics. At the same time, the neuron will not just act as a presence sensor (there is a phenomenon — there is no phenomenon), it will be the level of its activity to signal the severity of the factor for which it has learned. Interestingly, the nature of synaptic signals is not fundamental. With the same success, a neuron can tune in to the processing of wave patterns, patterns of topographic projection, or their joint activity.

It should be noted that the Hebbov learning, which distinguishes the first main component, is given purely illustratively to show that the local receptive field of any neuron of the cortex contains all the necessary information for training it as a universal detector. The real algorithms of collective learning of neurons, which emit many different factors, are organized somewhat more complicated.

Stability - Plasticity

Hebbovskoe training is very clear. It is convenient to use it to illustrate the essence of iterative learning. If we talk only about activating connections, then as the neuron learns, its weights are adjusted to a certain image. For linear adder activity is determined by:

The coincidence of the signal with the image that stands out on the synaptic balance causes a strong neuron response, the mismatch is weak. Teaching according to Hebb, we strengthen the weights of those synapses that receive a signal at the moments when the neuron itself is active, and weaken those weights on which there is no signal at that time.

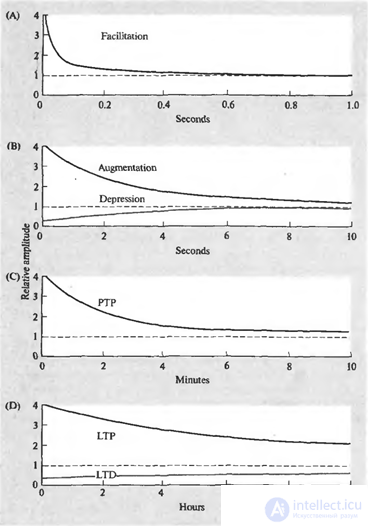

To avoid the infinite growth of weights, a normalizing procedure is introduced, which keeps their sum within certain limits. Such logic leads, for example, to the rule of Oya:

The most unpleasant thing in the standard Hebbovsky training is the need to introduce the coefficient of learning speed, which must be reduced as the neuron learns. The fact is that if this is not done, then the neuron, having learned from some image, then, if the nature of the signals given changes, it will be retrained to highlight the new factor characteristic of the changed data stream. The decrease in learning speed, firstly, naturally, slows down the learning process, and secondly, it requires no obvious methods to manage this decrease. Inaccurate handling at a learning rate can result in the “stiffening” of the entire network and immunity to new data.

All of this is known as the stability-plasticity dilemma. The desire to respond to new experience threatens to change the weights of previously trained neurons, but stabilization leads to the fact that the new experience no longer affects the network and is simply ignored. You have to choose either stability or plasticity. To understand what mechanisms can help in solving this problem, let us return to the biological neurons. Let us examine in more detail with the mechanisms of synaptic plasticity, that is, with the fact, due to which the synaptic training of real neurons occurs.

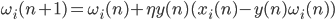

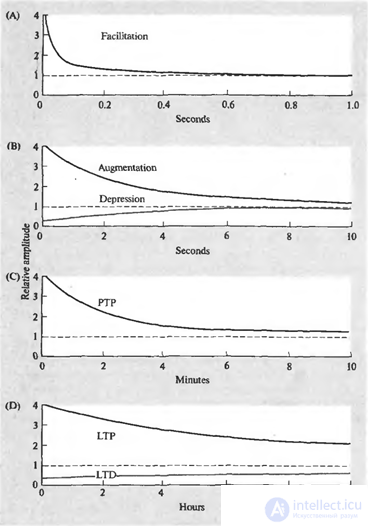

The essence of the phenomenon of synaptic plasticity is that the effectiveness of synaptic transmission is not constant and may vary depending on the pattern of current activity. Moreover, the duration of these changes can vary greatly and be caused by different mechanisms. There are several forms of plasticity (figure below).

Dynamics of changes in synaptic sensitivity. (A) - Facilitation, (B) - Strengthening and Depression, (C) - Posttetanic Potency (D) - Long-Term Potency and Long-Term Depression (Nicolls J., Martin R., Wallace B., Fuchs P., 2003)

Dynamics of changes in synaptic sensitivity. (A) - Facilitation, (B) - Strengthening and Depression, (C) - Posttetanic Potency (D) - Long-Term Potency and Long-Term Depression (Nicolls J., Martin R., Wallace B., Fuchs P., 2003)

A short volley of spikes can cause relief (facilitation) of the selection of a mediator from the corresponding presynaptic terminal. Facilitation appears instantly, remains during a volley, and is substantially noticeable for another 100 milliseconds after the end of stimulation. The same short exposure can lead to the suppression (depression) of the release of a neurotransmitter lasting several seconds. Facilitation can go into the second phase (gain), with a duration similar to the duration of the depression.

A long high-frequency pulse train is usually called tetanus. The name is connected with the fact that such a series precedes tetanic muscle contraction. Receipt of tetanus at the synapse, can cause the post-tetanic potency of the release of a mediator observed for several minutes.

Repeated activity can cause long-term changes in synapses. One of the reasons for these changes is an increase in calcium concentration in the postsynaptic cell. A strong increase in concentration triggers a cascade of secondary mediators, which leads to the formation of additional receptors in the postsynaptic membrane and an overall increase in receptor sensitivity. A weaker increase in concentration has the opposite effect - the number of receptors decreases, their sensitivity decreases. The first condition is called long-term potency, the second - long-term depression. The duration of such changes is from several hours to several days (Nicolls J., Martin R., Wallace B., Fuchs P., 2003).

How the sensitivity of an individual synapse changes in response to the arrival of external impulses, whether gain will occur or depression will occur, is determined by many processes. It can be assumed that this mainly depends on how the overall picture of the neuron's excitation develops and what stage of the training it is at.

The described behavior of synaptic sensitivity further suggests that a neuron is capable of the following operations:

- quickly enough to tune in to a certain image - facilitation;

- reset this setting at an interval of the order of 100 milliseconds, or translate it into a longer hold - gain and depression;

- reset the state of amplification and depression or translate them into long-term potency or long-term depression.

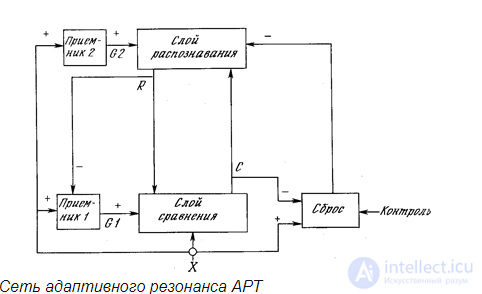

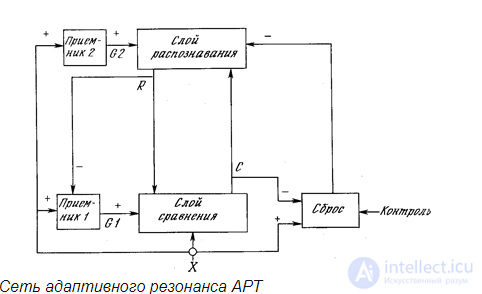

This degree of learning is well correlated with the concept known as the “theory of adaptive resonance”. This theory was proposed by Stefan Grossberg (Grossberg, 1987) as a way to solve the stability-plasticity dilemma. The essence of this theory is that the incoming information is divided into classes. Each class has its own prototype - the image that most closely matches this class. For new information, it is determined whether it belongs to one of the existing classes, or whether it is unique, unlike any previous one. If the information is non-unique, then it is used to refine the prototype class. If this is something fundamentally new, then a new class is created, the prototype of which lays down this image. This approach allows, on the one hand, to create new detectors, and on the other hand, not to destroy the already created ones.

Adaptive Resonance Network ART

Adaptive Resonance Network ART

The practical implementation of this theory is the ART network. At first, the ART network does not know anything. The first image submitted to it creates a new class. The image itself is copied as a prototype class. The following images are compared with existing classes. If the image is close to the already created class, that is, causes a resonance, then corrective training of the class image occurs. If the image is unique and not similar to any of the prototypes, then a new class is created, and the new image becomes its prototype.

If we assume that the formation of neuron detectors in the cortex occurs in a similar way, then the phases of synaptic plasticity can be interpreted as follows:

- a neuron that has not yet received specialization as a detector, but has come into activity due to wave activation, promptly changes the weights of its synapses, tune in to the picture of the activity of its receptive field. These changes are in the nature of facilitation and continue on the order of one tact of wave activity;

- if it turns out that in the immediate environment there are already enough neuron detectors tuned to such a stimulus, then the neuron is reset to its original state, otherwise its synapses go into a stage of longer retention of the image;

- If during the amplification stage certain conditions are fulfilled, then the neuron synapses pass into the stage of long-term storage of the image. The neuron becomes the detector of the corresponding stimulus.

And now we will try to systematize a little the idea of learning procedures relevant to artificial neural networks. Let's push back from learning goals. We will assume that we want as a result of training to obtain neuron detectors that satisfy two basic requirements:

- so that with their help it was possible to fully and adequately describe everything that happens;

- so that such a description would isolate the main laws peculiar to the events taking place.

The first allows, by memorizing, to accumulate information, without losing the details, which later may turn out to be important regularities. The second provides the visibility of those factors in the description on which decision making may depend.

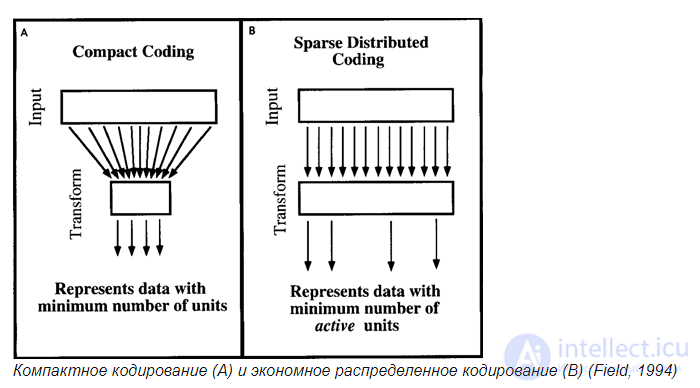

A well-known approach based on optimal data compression. So, for example, using factor analysis, we can get the main components, which account for the majority of the variability. Leaving the values of the first few components and discarding the rest, we can significantly reduce the length of the description. In addition, the values of the factors will tell us about the severity in the described event of those phenomena to which these factors correspond. But this compression has a downside. For real events, the first main factors in the aggregate usually explain only a small percentage of the total variance. Although each of little significant factors is inferior many times in magnitude to the first factors, it is the sum of these minor factors that is responsible for the basic information.

For example, if you take a few thousand movies and get their estimates from hundreds of thousands of users, you can carry out a factor analysis with such data. The most significant will be the first four - five factors. They will correspond to the main genre directions of cinema: thriller, comedy, melodrama, detective story, fantasy. For Russian users, in addition, a strong factor will emerge that describes our old Soviet cinema. Selected factors have a simple interpretation. If one describes a film in the space of these factors, then this description will consist of coefficients, telling how much one or another factor is expressed in this film. Each user has certain genre preferences that influence his assessment. Factor analysis allows you to isolate the main directions of this influence and turn them into factors. But it turns out that the first significant factors account for only about 25% of the variance of the estimates. All the rest falls on thousands of other small factors. That is, if we try to compress the description of the film before its portrait in the main factors, we will lose the bulk of the information.

In addition, we can not talk about the unimportance of factors with low explanatory power. So, if you take several films of the same director, their ratings are likely to be closely correlated with each other. The relevant factor will explain a significant percentage of the variance of the ratings of these films, but only these. This means that since this factor does not appear in other films, its explanatory percentage in the entire volume of data will be insignificant. But it is for these films that it will be much more important than the first main components. And so for almost all small factors.

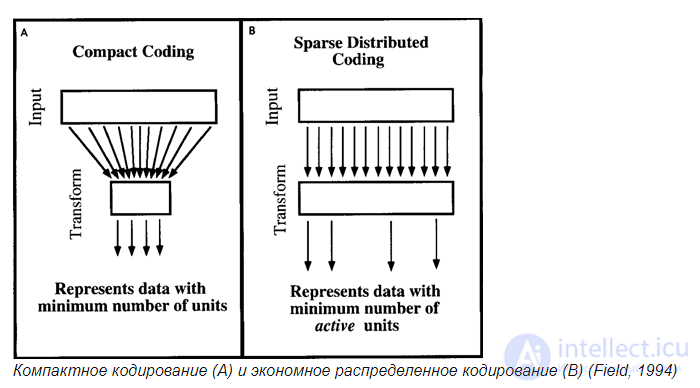

The arguments given for factor analysis can be shifted to other methods of coding information. David Field, in a 1994 paper “What is the purpose of sensory coding?” (Field, 1994) addressed similar questions about the mechanisms intrinsic to the brain. He concluded that the brain does not compress data and does not strive for compact data. The brain is more comfortable with their discharged representation, when having to describe many different features, it simultaneously uses only a small part of them (figure below).

Compact coding (A) and economical distributed coding (B) (Field, 1994)

Compact coding (A) and economical distributed coding (B) (Field, 1994)

And factor analysis, and many other methods of description are repelled from the search for certain patterns and the allocation of relevant factors or characteristics of classes. But often there are data sets where this approach is practically inapplicable. For example, if we take the clockwise position, it turns out that it has no preferred directions.It moves evenly across the dial, counting down hour after hour. To transfer the position of the hand, we don’t need to single out any factors, and they don’t stand out, it’s enough to split the dial into the corresponding sectors and use this partition. Very much the brain deals with data that does not imply division, taking into account the density of the distribution of events, but simply requires the introduction of some interval description. Actually, the principle of adaptive resonance offers a mechanism for creating such an interval description, which is able to work even when the data space is a fairly uniform distributed environment.

Selection of the main components or fixation of adaptive resonance prototypes is not all methods that allow neural networks to train neuron-detectors convenient for the formation of description systems. Actually, any method that allows you to either get a healthy division into groups, or to highlight any pattern, can be used by a neural network that reproduces the cerebral cortex. It is very likely that the real crust exploits many different methods, not limited to those that we cited as an example.

While we talked about the training of individual neurons. But the main information element in our networks is a pattern of neurons, only he is able to launch his own wave. A separate neuron in the field is not a warrior. In the next section, we describe how neural patterns can arise and work that correspond to certain phenomena.

Comments

To leave a comment

Logic of thinking

Terms: Logic of thinking