This series of articles describes a wave model of the brain that is seriously different from traditional models. I strongly recommend that those who have just joined begin reading from the first part.

The information with which the brain operates must, on the one hand, sufficiently fully describe what is happening, on the other hand, it must be stored so as to allow the performance of the operations required by the brain. In principle, the format for describing information and its processing algorithms are closely interconnected things. The first largely determines the second. Therefore, speaking about how the data stored by the brain can be organized, we, whether we like it or not, largely predetermine a system of subsequent thought processes. Since we are going to talk about the principles of thinking later, now we will focus only on how to ensure the completeness of the current description and subsequent storage of information. At the same time, implying that if, having come to thinking, it turns out that the chosen data format fits the required algorithms, it means that we were lucky and we took the right path.

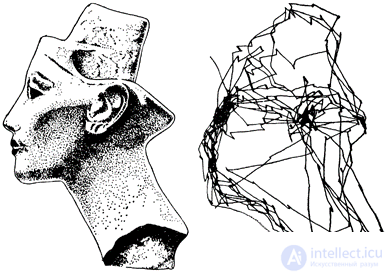

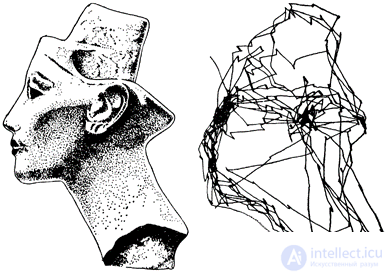

To understand what kind of descriptions the brain uses, let's follow the sequence of visual perception. Looking at the image, we “scan” it with quick eye movements, called saccades (drawing on the KDPV). Each of them places in the center of view one of the fragments of the overall picture. On the zones of the visual cortex, descriptions arise that correspond to what we see at this moment in the center, what the periphery sees and what the displacement is as a result of the saccade that has just been done. Each following saccade creates a new picture. These descriptions follow each other one by one.

So, looking at the face, we first, for example, clearly see and recognize one eye, the one to which the eye is directed. The remaining elements of the face that fall on the relative periphery of vision - the nose, mouth, and so on, we learn with less, but the same high enough probability. After each saccade, the central fragment changes, but the common set of recognized elements remains unchanged.

In principle, each of these separate descriptions arising between saccades is enough to say that we have a face and even know who owns it. But each individual description reliably speaks only of the object, which for it is located in the direction of view. The remaining objects are determined fairly approximately.

If we want to get a more complete and detailed picture of the face, then a combination of all the descriptions that will arise during the scan will be suitable for this. In this case, it will be important not only the description of what objects are recognized for, but also information about the accompanying glances of sight. And here we come to a very important point. What is the final description that the visual analyzer should produce? Just a picture of the activity of a number of concepts? This corresponds only to the part of the description that we see right now. But what about the rest? It turns out that a correct, not losing information, description is a package of simpler descriptions following one after another. Where each of the layers of such a temporary package describes only some of the information, and a complete description is obtained as their combination. This is true provided that all the descriptions in the package correspond to one event, that is, received before the global shift of our attention.

If you take a snapshot of the activity of the cerebral cortex, the description of what is happening can be compared with the listing of active concepts in each of its zones. But such a description has a significant drawback. Suppose we want to describe the still life depicted in the figure below.

We can do this, for example, like this:

- Vase just to the right of the center;

- Bouquet in a vase;

- Towel to the right of the vase;

- White flower on the towel;

- Bowl with raspberries on the left;

- Raspberries on the sheet to the left of the bowl;

- Three raspberries in front of a bowl;

- Raspberries to the right of the vase.

General description consists of a set of such short descriptions. Each short description can, with some reservations, be replaced by a listing of the concepts included in it. But if we want to collect the final description, simply adding all the concepts involved in the short transfers, then we will fail. When adding, some of the information will disappear, since it becomes unclear what is related to what. But, in addition, it turns out that some concepts need to be used several times. For example, it is raspberry on the left, on the right, and in front of the bowl. And if we want to use this “just assembled” description as an analogy of how such a still life is described on the bark zones, then it turns out that the generalization of “raspberry” is the same and it cannot be “active three times” at the same time. The way out of this situation, which seems to me quite logical, is to use the package description. Each simple description can consist of a banal listing of active concepts. The full description is obtained as a set of simple descriptions. Since simple descriptions are spaced apart in time, then, on the one hand, it is clear what is relevant, and, on the other hand, the same concept can occur several times in different layers of a package in different contexts.

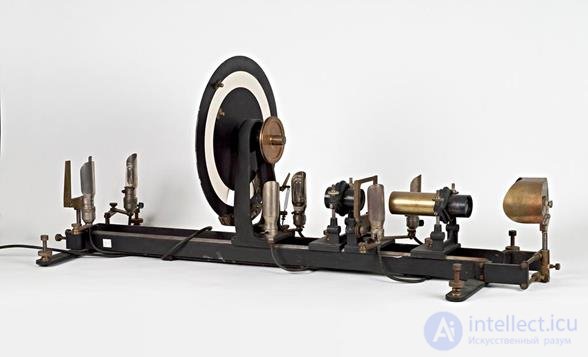

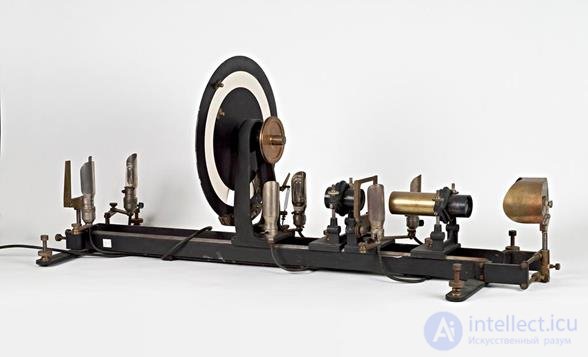

Such a batch view is very well correlated with reasoning about the amount of attention a person has. Psychologists, studying the properties of attention, have established that there is a limit to the number of objects on which a person can simultaneously concentrate. Usually this limit does not exceed seven objects. The founder of experimental psychology, Wilhelm Wundt, was the first to measure attention span using a mechanical tachistoscope.

Tachytoscope - a device with which you can show consistent visual stimuli

Tachytoscope - a device with which you can show consistent visual stimuli Estimate the amount of attention is very simple. Look at the previous still life and try to count how many individual elements you are capable of, no, not remember, this is different, but keep in your head at the same time. Or take a seven-digit phone number, for example, 1145618 and try to “keep” it in your head. Most likely, that he did not disappear, you will have to loop him to repeat himself. If there are more than seven digits in the number, then there is a great chance that it will not be possible to keep them all in memory. The maximum number of perceived objects of still life or numbers at once gives an estimate of the amount of your attention.

The assumption we made about the batch representation of information in the cerebral cortex allows us to compare each of the objects held in attention with one of the layers of the information package.

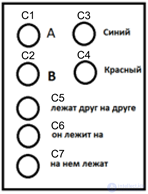

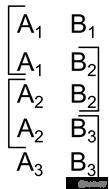

If we imagine a cortex consisting of a small number of concepts, capable of formulating very simple thoughts about two objects “A” and “B”, then the package corresponding to the thought: “the red object A lies on the blue object B” will look as shown in the figure below.

Sample Information Pack

Sample Information Pack Coding of complex descriptions

Let us return to the memory and try to systematize what types of information, and, accordingly, the types of descriptions our brain can handle.

The first type is a simple description that corresponds to the picture of the instantaneous activity of the cortex. This is a combination of those concepts that are detected by the brain right now.

The second type is a package of simple descriptions corresponding to one event, one thought. In the package, the order of the descriptions is irrelevant. Rearranging the layers of a package does not change the general meaning of the statement. Package recall is a series of simple descriptions following one after another.

The third type is a positional description. In such a description, the connection of some objects with others that are in a certain system of relations with them is preserved. For example, a variation of such a description is a spatial description. When we do not just fix our position in space, but we associate it with certain descriptions with the location of other objects.

The fourth type is a procedural description. Such a description, in which the sequence of changing images is important and the intervals that accompany it. For example, the perception of speech is determined by the sequence of sounds, and the ratio of intervals forms intonation, on which the general meaning of the phrase heard strongly depends. Recalling a procedure is the reproduction of the corresponding sequence of images.

And the fifth type is a chronological description. Fixation on long periods of time in which sequence and with what time intervals certain events occurred. The opportunity to remember for chronological memory is not the reproduction of everything related to one chronology at once, but the ability to move from one description to another, associated with it a common temporal sequence.

It is easy to see that many descriptions are somehow tied up for a while. A batch description is a series of successive images. The procedural description takes into account the sequence of events. The chronological description requires taking into account the positioning of events in time.

Such dependence of descriptions on time was the reason for the emergence of corresponding models. The most famous of these is the concept of hierarchical temporal memory (HTM) promoted by Jeff Hawkins (Hawkins, 2011). He and his colleagues proceed from the fact that the temporal change of events is the only thing that allows us to link together separate informational images. From this it is concluded that the basic information element of the cortex should work not with static images, but with a time sequence. In the HTM concept, the information storage element is a sequence of signals expanded in time. Recognition is the definition of the coincidence of two sequences. Special emphasis is placed on the ability of the HTM to predict. As soon as a neuron recognizes the beginning of a sequence familiar to it, it becomes able to predict the continuation it remembers from its own experience. The description of the current picture in the HTM is the activity of those neurons that responded to the current change of events.

The complexity of this approach is quite obvious. First, the requirement of respecting the time scales. A slight acceleration or delay in data entry can disrupt the recognition algorithm. Secondly, the need to translate all static images into temporary sequences before the cortex can handle them. Etc.

In our model, the identifier system gives us a universal tool that is equally well suited for describing all possible types of memory. The basic idea is simple - every simple description is a composite identifier that contains everything needed to indicate the entire set, both associative and temporary relationships.

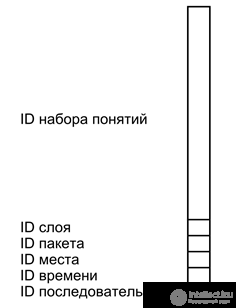

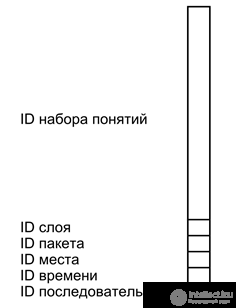

The figure below shows the conventional image of such a simple description. A simple description is a wave that carries several sets of identifiers of different types. The main content is encoded by a set of identifiers of concepts that describe the essence of what is happening. The layer identifier marks the main content, separating it from the rest of the simple descriptions. The package identifier combines several layers belonging to the same complex description. Identifiers of place, time, and sequence create a system of corresponding links between complex descriptions.

Simple description format

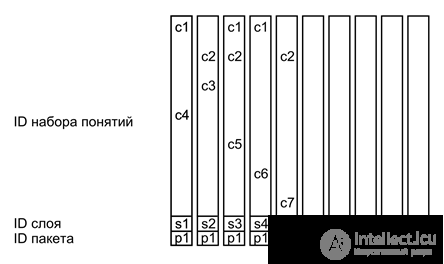

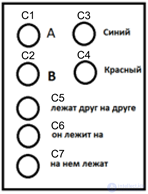

Simple description format Let's take the previous example and designate the waves of identifiers corresponding to the concepts used (concepts) as C1 ... C7 (figure below).

Concepts used to describe

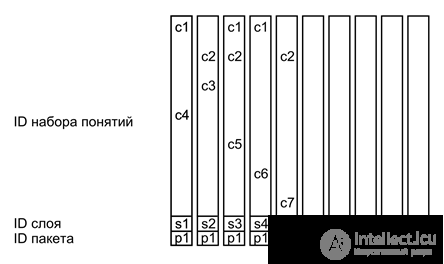

Concepts used to describe Then the description of the fact that “the red object A lies on the blue object B” will look as shown in the figure below.

An example of a complex description

An example of a complex description In this example, each of the layers of a package is a simple description with its own layer ID. All package layers have a common package identifier p1. When one complex description ends, the other following it has a different p2 package identifier (the concepts of the second description are not shown in the figure).

For this design to be workable, the brain needs a fairly complex system that creates identifiers that form the packets. Moreover, for each of the zones of the cortex may need its own set of such identifiers, appropriate for it.

For example, take a sequence of visual perception. The intermittent micromovements of the eyes, called microsaccades, cause the eye to scan a small portion of the image that falls on the center of the retina. All images that are obtained in the process of such a scan, presumably can be combined with a common identifier. Eye micro-movements are controlled by the upper hillocks of the quadrilateral. It can be assumed that they encode such an identifier. After several microsacades, a strong jump occurs, called a saccade (above, in the picture with the head of Nefertiti, the saccades are shown). Each saccade causes a change in the identifier of microsacdes.

It can be assumed that microscopes are fundamentally important for the primary visual cortex. The common identifier informs the cortex that a series of consecutive images describes the same object, but in different positions on the retina, which allows combining them into a single description and realizing the invariant position on the retina recognition.

A longer event is a series of saccades. Since the series refers to looking at a single picture, the resulting descriptions can also be linked to each other by another common identifier — the saccad identifiers. But this identifier is no longer essential for the primary, but for the secondary and deeper levels of the visual cortex, where the subsequent processing of information takes place. The identifier informing the cortex that everything that we see during a series of saccades is the same picture, allowing us to relate the same images between different places of the retina to each other.

The change of the saccade identifier should occur when the picture under consideration changes significantly. For example, with a strong turn of the head, switching attention, a change of plan or scene in the movie. Switching attention can be encoded by elements of the limbic system of the brain and spread to many, tied to this, areas of the cortex. At the same time, the description system contains hippocampal identifiers encoding spatio-temporal descriptions of events. In short, the system of identifiers that define a packet can be quite complicated, and is determined by the characteristics of the information that each particular zone of the cortex deals with.

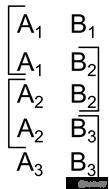

Using identifiers it is easy to organize the fixation of a sequence of events. For example, if you take an identifier consisting of two fragments, then alternately changing one of them, you can get the associative connectedness of neighboring descriptions (figure below).

Sequence encoding

Sequence encoding Each such identifier will contain an element from the previous and subsequent identifier. Having remembered a temporal sequence of images with such identifiers, we will be able to find its two neighbors in the time scale for each image. By simply complicating the identifier, it is possible to encode not only the general connectivity, but also the direction of the flow of time.

It should be noted that in our model, each memory has a rich system of identifiers. This allows access to memories through many completely different associations. You can recall something based on the coincidence of the descriptions. You can associate informational pictures at the place or time of the described events. You can play a sequence of images related to a single event. It is easy to see that such access to memories has much in common with the approaches used to create traditional relational databases.

Comments

To leave a comment

Logic of thinking

Terms: Logic of thinking