For those who have just joined, I advise you to start with the first part, or at least with the description of the wave model used by us. The essence of the wave model is that information is encoded simultaneously in two ways. The first method is the patterns of evoked activity, corresponding to the phenomena detected by the neuron detectors. The second is wave identifiers propagating from patterns of evoked activity and carrying unique patterns. The uniqueness of the pattern of each wave allows you to find out about its activity at a distance from the signal source. With this approach, the mismatch between the volume of the cortex zones and the number of fibers in the bundles projecting information from them to other zones is well explained by Mac-Calloc and Pitts.

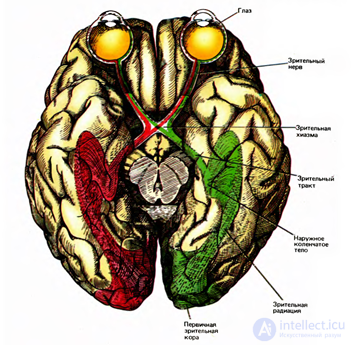

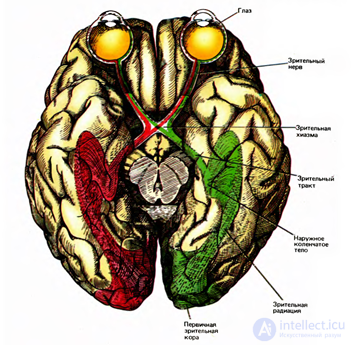

From our reasoning it follows that the brain has two types of projections. The first most understandable type is the so-called topographic mapping. For example, the visual signal from the eyes along the optic nerves spreads to the chiasm. There, the fibers are redistributed so that one hemisphere receives fibers only from the left, and the other only from the right halves of the retina. Further, along the optic tract, information enters the external articular body, and from there to the visual cortex. The optic nerve contains about a million fibers, which corresponds to the resolution that is available to the eye. On the primary visual cortex, this information is projected through visual radiation. Visual radiation is the uniform distribution of a bundle of nerve fibers over the entire area of the primary visual cortex (figure below). The topographicality of this mapping is that the signals adjacent to the retina are near and in their projection onto the cortex. With such a transfer, the positioning of the signals is maintained. The image from each place of the retina falls into its area of the cortex, which allows you to save information about the relative position of objects.

The visual path (Hubel, 1988)

The visual path (Hubel, 1988)

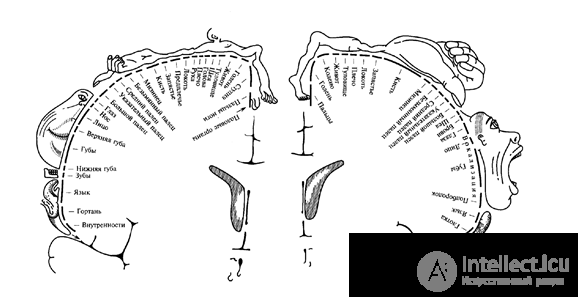

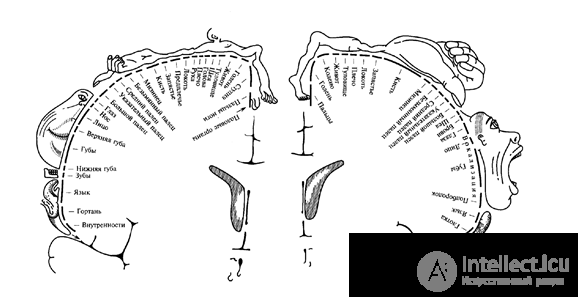

Similarly, with the preservation of topographic ordering, the signals are projected onto the sensor zones. This is where the famous Penfield map appears, illustrating the representations of the various parts of the body on the sensory and motor cortex (figure below).

Penfield man

Penfield man

Traditional hierarchical multilayer neural networks, for lack of the best, copied the principle of topographic projection, declaring a decrease in the size of the layers and an increase in the initial receptive fields of their neurons as information moves upward.

However, the real system of connections in the white matter of the brain is fundamentally different. Between the zones of the cortex there are no “thick” connective neural loops capable of global transmission of the pattern of activity from one zone to another. The entire system of projections consists of relatively thin beams. Moreover, the contacts of these beams with the zones of the cortex do not diverge like a fan and do not form radiation, but have dense “point” connections. This is especially clearly seen on real images of white matter, where each of the projection directions is tracked separately (figure below).

The structure of the white matter of the brain (Fallon)

The structure of the white matter of the brain (Fallon)

It can be confidently asserted that the connections between the zones of the crust are made not by topographic projections, but by connections of a fundamentally different type. We call this second type of connection wave tunnels.

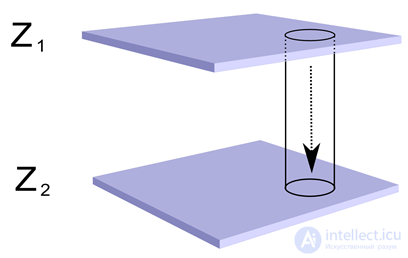

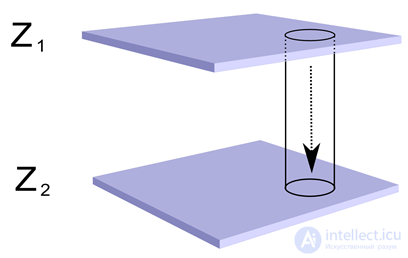

Take a couple of zones of the cortex and combine their two small, randomly selected areas. We make it so that the activity of the upper region is copied to the lower region (figure below). In this case, you can not care about the topographic projection. You can mix the projecting fibers, and also skip some of them, making the projection discharged.

Wave tunnel

Wave tunnel

Such a connection will not help us with the transfer of the entire picture of the activity of the transmitting zone. But it turns out that the whole picture is not needed. Through each place of the cortex pass identification waves that carry information about all the stable patterns of this zone. That is, if the bark zone has learned to respond to certain images, then in its small area we will see all the existing identifiers. Everything is exactly as in an optical hologram, where each fragment stores information about the entire image.

This means that by transferring the activity of a small area of the cortex from one zone to another, we will receive on the receiving area a section that generates certain patterns that are no different, in essence, from those that occur during wave propagation. Such a site will definitely begin to train its bark in the distribution of repetitive patterns. Over time, this will lead to the fact that the identification waves will be transmitted through such a tunnel and continue to spread to the receiving cortex.

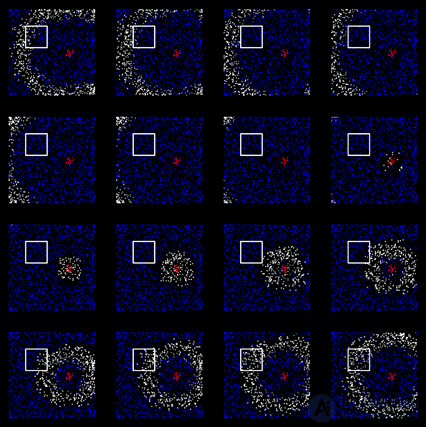

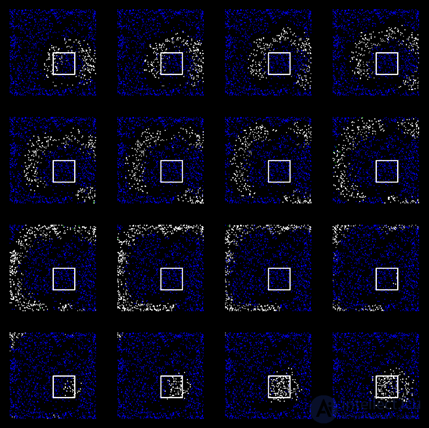

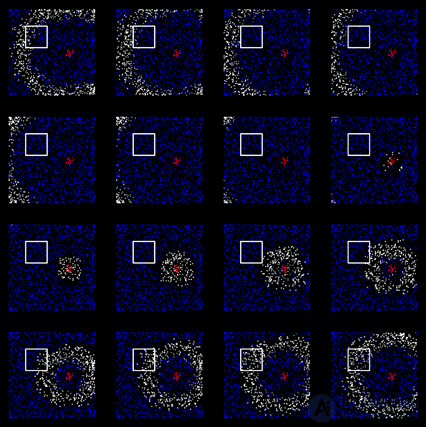

This process is well observed in modeling. Below are two mapped wave propagation patterns. The top picture is the projecting crust, the bottom one is the host crust. Squares are allocated areas connected by a tunnel.

Activity of the projecting cortex

Activity of the projecting cortex

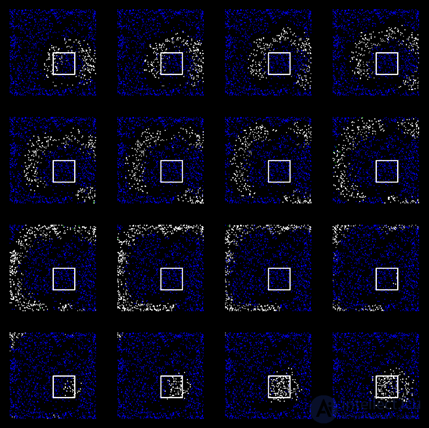

Activity host bark. The images correspond to the same measures of the projecting cortex.

Activity host bark. The images correspond to the same measures of the projecting cortex.

It can be seen that when the wave passes through the tunnel region in the transmitting zone of the cortex, it triggers the wave in the receiving zone (already trained zones are shown). It is important that the resulting wave retains all the properties of the original identifier. For each phenomenon, as well as on the original cortex, its distribution pattern characteristic only for this phenomenon is invoked on the crust of the recipient.

Below is a video obtained by modeling. On the left there is already a trained zone, and on the right is the zone that just started the training:

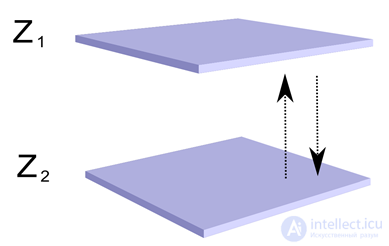

Counter projections

Counter projections

If two zones of the cortex are joined by opposing projections (picture above), then an interesting effect can be obtained. The identifier from the first zone will move to the second zone, spread there, and then come back and spread from the point of contact of the wave tunnel. At the same time, if the transfer between zones occurs through myelinated fibers, the pulse propagation speed in which is about 100 m / s, then the signal travel time for back and forth for zones located 10 centimeters from each other, when closely contacting projection beams can be estimated a few milliseconds. This means that for a wave of identifiers with a period of the order of 100 milliseconds, the returned signal will almost merge with the main wave. So, it will be taken into account as part of the existing identifier.

As a result, if in the second zone of the cortex in some way the identifier that came earlier from the first zone is reproduced, then, having passed through the wave tunnel back to the first zone, it will cause an identification wave already known to this zone. Such a mechanism allows not only to transfer information from one zone to another, but also to return it in a form that is understandable for both zones of the cortex.

If we compare the topographic and wave projection, then each is good for its own purposes. Topographic projection is necessary where it is impossible to lose information related to the relative position of the active elements. Wave projection is convenient when it is possible to form a description built on a simple enumeration of concepts.

The general information picture that the brain operates on is a collection of descriptions. Each of the zones of the cortex forms a description in the factors peculiar to it. In addition to a set of factors, the zones also differ in the form of the description. Topographic shape preserves the properties characteristic of the image when the value has a mutual spatial arrangement of elements. The wave form of the description is equivalent to a disordered enumeration of factors that have shown their activity.

In addition to solving the problem of narrowness of the channels, the wave model allows us to remove the essential contradiction inherent in traditional models associated with the locality of the receptive fields of neurons of the upper levels. The essence of the contradiction is that with each new level, neurons must distinguish more and more generalized signs and concepts, but for this they need an ever wider coverage of the observed properties. Since real neurons at all levels have limited receptive fields, the classical model has certain difficulties in explaining this.

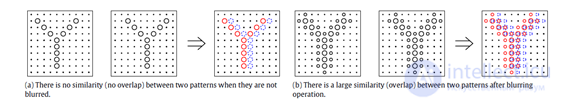

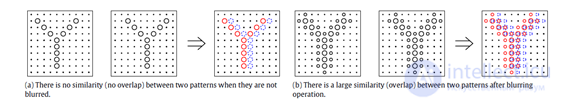

If we recall the neocognitron, then all its complex neurons must be serviced by the planes of simple cells. Simple cells that are in the same plane have the same weight and simultaneously monitor all possible sections of the previous layer. Where we have a wave delivers the necessary information to each location, in a neocognitron in each position a set of simple neurons scans the entire surface for the presence of the required pattern. Such a scan requires total tracking, since the offset of just one position completely changes the pattern. Blurring can be used as a way to alleviate the problem (figure below). During erosion, the requirement for totality is somewhat weakened, since each simple neuron acquires the ability to react in a certain range of shift.

Improving recognition through erosion (Fukushima K., 2013)

Improving recognition through erosion (Fukushima K., 2013)

But the fact that you can somehow use it for the initial processing of images turns out to be poorly applicable for more abstract zones of the cortex, where the patterns of evoked activity have a “sharp” setting.

The use of the wave representation completely removes the question of locality of receptive fields. It turns out that a neuron should not follow its entire cortex with its synapses. If the "bark" does not go to Mohammed, then Mohammed goes to the "bark". The waves of identifiers themselves bring to each neuron all the necessary information, for the perception of which it is quite sufficient for it to only closely monitor its immediate environment, which completely shows it the character of the passing waves.

From the wave model there are several properties that are in good agreement with the existing ideas about the system of projections of the real brain:

- wave tunnels are compact across the area of contact with the cortex, which means that several contact pads can exist without interfering with each other;

- tunnels are not critical to the place of removal of information and to the place of entry into the cortex;

- tunnels do not require total removal of the activity of all neurons in the contact area;

- for tunnels, it is not important to maintain the orderliness of the fibers; the fibers can be randomly mixed inside one beam, which does not affect the result of the transfer.

From the wave paradigm there arises an understanding of information processes inherent in the brain, which is quite different from what we used to use to describe computer systems. A traditional computer contains many nodes, each of which performs its function. Programs contain a variety of modules focused on specific tasks. Nodes at the physical level, and software modules on the logical exchange of data. The result is the execution of predefined algorithms. Malfunction or error in any element in most cases leads to the impossibility of completing the algorithm.

The brain contains areas of the cortex, which, learning, acquire their specialization. The essence of specialization is that in which terms the zone of the cortex will build its description. A description created by a zone of the cortex, through a system of projections, becomes available to all those zones with which it has projection contact. The system of projections has evolutionarily acquired such a configuration that allows you to get the most complete display of what is happening.

Visualization of the monkey brain projection system (IBM Research)

Visualization of the monkey brain projection system (IBM Research)

It should be noted that in addition to projections transmitted through projection fibers, information can spread from one zone to another, simply by crossing the conditional zone boundary. The wave of identifiers, reaching the edge of the zone, can spread further to the neighboring zone. Whether this happens or not, it can be determined by the coincidence or mismatch of the types of neurotransmitters and extrasynaptic receptors characteristic of the neurons of these zones. If this is so, then the existing projection linking schemes should be supplemented with such “neighbor” projections.

The described projection ideology has surprising fault tolerance. Turning off a zone does not lead to the failure of the entire structure, but only makes the description system poorer. Error on any zone is not fatal, as it can be compensated by the work of other zones.

The work of the brain can be compared with the system of news agencies, newspapers and websites. They all publish their description of what is happening. Many borrow information from each other. Information can be presented and interpreted by each of them individually. Some have their own specialization: someone has a bias on political news, someone on cultural news or technology. Turning off one of the sources does not break the entire system, but only slightly impoverishes the information space. Each of the participants does not totally follow all the others, but has its own well-established list of tracking, which includes the sources most interesting for him.

Let me give you another analogy. Imagine a system of institutions that work together on a global project. You can break the work into parts and give the institutes narrow non-intersecting tasks. When each of them performs his work, it remains to put everything together and get the final draft. Another approach is to lean on everyone at once and, duplicating each other, cooperating, using other people's designs, create several options and then choose the best one. Obviously, the first option has many advantages, at a minimum, clarity and controllability of what is happening. In the second variant, the process is not obvious, and the result is not guaranteed. But it turns out that as we learn and gain competitive experience, with the right incentive system, the second option can produce results that far exceed the first scheme.

In the next part I will try to describe how, in practice, you can use the knowledge of the principles of projecting information between the zones of the cortex.

If somewhere is too brief, incomprehensible or vaguely stated, please write in the comments.

Comments

To leave a comment

Logic of thinking

Terms: Logic of thinking