Lecture

Contrary to the opinion prevailing in some editions, reliance on the law not only does not complicate the technology of mass information production, but, on the contrary, makes it possible to debug it to the level of standard operations, and therefore to simplify it. We will see this on the example of a number of main links of the editorial conveyor.

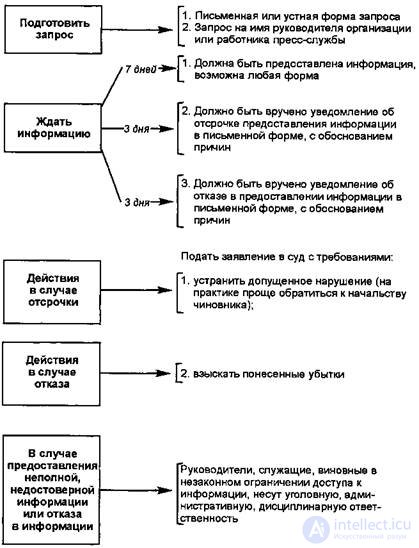

Collection and dissemination of information. The Commission on Freedom of Access to Information has developed an algorithm for the actions of a journalist requesting information from state resources. In its main provisions, it is also suitable for contacts with public organizations, since it relies on regulatory documents of wide scope. Let's reproduce this scheme in general terms.

The proposed scheme reflects the opportunities that are provided to the press, and involves the selection of the most appropriate course of action in each case. So, knowing that a request can be made in any form, we most often refer to the source of information orally, either in person or by phone. However, if there are concerns that we will be denied information, it is better to prepare more thoroughly: write a request (keep a copy in the editorial office), use special forms for such correspondence with relevant excerpts from media legislation, find out the date the request was recorded at the place of receipt (to control deadlines for receiving a response or refusal), etc. It is unlikely that it will be possible in such a way to collect facts for a news column, but when working on analytical texts it may turn out to be the only correct one, especially if the rights of a journalist are asserted through court.

The algorithm of actions considered by us is built on norms that are contained in several legal acts. Therefore, it reflects a fairly spacious range of means of combating interference in journalistic work. This has to be emphasized because the Criminal Code (the article “Hindering the lawful professional activities of journalists”) only refers to hindering them by coercion to disseminate or to refuse to disseminate information. It is clear that in reality there are much more ways to “shortcut” the media. Here, the Laws “On Mass Media”, “On Information, Informatization and Protection of Information” and others come with their provisions on liability for infringing the freedom of information exchange.

At the stage of information dissemination (publication of texts), it is also necessary to use a set of special methodological methods of labor. They are mainly related to the verification of facts and the assessment of the admissibility (or inadmissibility) of the publication. The general rule is to conduct an in-depth examination of the texts in terms of their legal consequences, especially in dubious, ambiguous situations.

In some cases, the responsibility of journalists is removed. According to the Law “On Mass Media” (Article 57), there will be no complaints against them if the published information is present in mandatory messages (for example, in documents of state bodies that established this media); obtained from news agencies; contained in the response to the request for information or in the materials of the press services; are literal reproduction of fragments of speeches of deputies, delegates of congresses, conferences, etc. and official speeches of the officials contained in the author's works, broadcast without prior recording (live), or in the texts that cannot be edited, are literal reproduction of messages distributed to other media ... However, most of the listed points contain reservations and subtleties that can negate the apparent freedom from responsibility.

Let us dwell on the reproduction of publications of other media. One of the metropolitan editions reprinted excerpts from the Tajik newspaper, where a certain person was accused of committing crimes. The Moscow edition felt protected by the Law “On Mass Media” and was not hampered by the verification of facts. However, she did not take into account the conditions for the application of article 57: it is valid if the primary source media can be brought to justice in Russia. The Tajik newspaper was liquidated by that time. As a result, the claim of the “hero” of the publication to the capital edition was satisfied. In another case, a regional newspaper reprinted material from Moscow journalists. But the claim for the protection of honor and dignity was filed specifically to her, and not to the original publication. The offended party referred to the fact that during the reprint three spelling errors that were encountered in the original were corrected. Consequently, this is not the literal reproduction of the first publication [11]. Finally, even if the editors faithfully reproduced the documentary sources listed above, they still face trouble: the person injured in the original source may demand a refutation of inaccurate information about the media that circulated them.

The next stage in the functioning of the journalistic text, after the dissemination of information, is connected with the social efficiency of publications. Of course, the effectiveness of media speeches is determined by the depth and constructiveness of the problem analysis, and not by the order “respect the printed word”. But the complete absence of mechanisms for responding to public opinion cannot be considered a democratic order. In Russian law, there are rules that encourage officials to work with signals and proposals of the press, and we must skillfully use them. The presidential decree “On measures to strengthen discipline in the civil service” (1996) obliges the heads of the executive authorities to consider media information about the failure of officials to comply with laws, decrees and court decisions for three days. After two weeks, it is necessary to inform the editorial staff and state control bodies of the results of the consideration of information. It is a pity that journalists are not well aware of this decree and rarely resort to its power.

Much more "lucky" with the use of other regulations - that regulate the activities of law enforcement. According to the criminal procedure legislation, the reasons for initiating a criminal case are, in particular, statements and letters from citizens, reports from organizations and officials, as well as articles, notes and letters published in the press. Documents passing through the hands of journalists can figure in all these qualities. Even if the text was not printed, it belongs to the category of letters of citizens. When the editors send reader correspondence or publication to the police or prosecutor’s office, its materials acquire the status of messages from organizations or officials. This is important to keep in mind to journalists of audiovisual media, because the law does not consider their publication as a reason for initiating a case (only the press is mentioned in the documents), but television and radio companies belong to organizations to the same extent as newspaper editors.

Similar rules are introduced in other legal acts. Thus, under the Law “On Federal Tax Police Authorities”, these bodies are obliged to receive and register messages (including publications in the press) about tax crimes, the police (according to the Law “On Police”) must receive and register the information received about crimes. However, lawyers draw attention to the fact that the legislator does not oblige law enforcement agencies to study periodicals for finding information about crimes [12]. A paradoxical situation may arise: the public widely discusses the exposing publication, but the course of the case is not given. It is not difficult to avoid an incident if the editors establish a procedure for the mandatory distribution of publications and letters to the institutions concerned - administrative and law enforcement. Contrary to popular belief, the authorities and control are interested in using journalistic information. In the wake of the Izvestia speech, the State Duma approved a commission to verify the facts of human rights violations in the detention centers of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The Russian government has suggested that the media send materials about corruption in its office to law enforcement agencies. The public relations center of the Prosecutor General’s Office daily prepares a summary of media publications on the most significant violations of the law ... It depends on the perseverance of journalists how systematic and productive this interaction will be.

Media relations with the court and the investigation. Within the framework of this extensive subject matter, we will focus, on the one hand, on the editorial staff’s obligation to provide the requested materials (in particular, received confidentially) and, on the other hand, on the announcement of investigative and judicial information.

The first question does not have a clear answer. The journalist keeps the source of information secret for ethical reasons, as well as in order not to lose his confidence and readiness for further cooperation. Thus, the correspondent is facing an unusually difficult choice between law-abiding and professional ethical obligations. All over the world, the protection of sources of journalistic information is perceived as a delicate problem requiring special approaches. In the United States, for example, more than half of the states have enacted laws that provide media employees with relative or absolute rights not to disclose information received privately. Putting a journalist in prison for refusing to disclose information known to him there is considered “not American-style”, the courts rarely try to get journalists to speak, and those, respectively, are in no hurry to share their information [13].

In Russia, criminal procedural legislation allows law enforcement agencies to request materials from the editorial office related to the publication, which gives rise to a criminal case. It is also allowed to receive written explanations from journalists, to call them for conversation.

The question, however, is whether the case has already been initiated or is it only a preliminary check of the report on the act that has signs of a crime. During the pre-investigation check on a journalist there is no obligation to provide materials, give explanations, come to the police on call, etc. Coercive measures are not provided in this case. Literally: the right to request information is there, but the obligation to open it is not. Relationships are fundamentally different when a criminal case is initiated. Here, media workers have a legal obligation to satisfy the requirements of the investigation. The provisions of the Law “On Mass Media” on the protection of confidentiality of information lose their force, since criminal proceedings are conducted in accordance with the criminal procedure legislation, and priority is given to it. In turn, representatives of the investigation receive additional rights: they are allowed to conduct searches in the editorial office and withdraw the necessary documents, and if the journalist refuses to give out materials, they are voluntarily withdrawn under compulsion. Coercion is also permitted when a journalist fails to appear for interrogation as a witness. Let us pay attention to the fact that a search or seizure of documents can only be carried out on the basis of a special decree, and it will not be superfluous to get to know him before, say, a search in an office office begins.

Now let us imagine that the workers of the media and law enforcement agencies are changing places: information about the course of the preliminary investigation or the trial became known to journalists . There are also nuances that affect the degree of freedom of the reporter in the announcement of the facts. In general terms, the same rules apply as when working with state secrets, because information about the investigation is among the secrets protected by law. If a journalist was officially admitted to her (with the written permission of the investigator or the prosecutor), then he is criminally responsible for making her public - he is specifically warned about this. The prosecutor's office may deliberately declassify any information for publication - in the form of interviews, press conferences, etc. Then the responsibility for disclosure falls entirely on her. But what if the permission to publish was not, and the information still fell into the hands of the reporter? Let us recall how this issue was resolved in connection with a state secret: the people responsible for its service are responsible for making it public. It seems that even when the secrets of the investigation were disclosed in the actions of the journalist, there is no corpus delicti - if no one has notified him that the materials are closed to print.

There is one plot in the topic we are studying, which is usually regarded as a classic journalistic mistake. We are talking about premature - until a court decision - declaring a person a criminal. Indeed, only the verdict gives official grounds instead of the words “accused”, “suspect”, “defendant”, “defendant” to write or pronounce on the air: “criminal”. By the way, journalists are in no hurry to call the crime and the incident itself, without delving into the fact that not every offense can be called this term. It is used in criminal law, but does not apply in administrative or civil law. In addition, considerable efforts by the investigation and the court are required in order to ascertain that there is a so-called event and corpus delicti in the incident, stipulated by certain articles of the law.

Let's return to the journalistic verdict. Without long discussions it is clear that the press is not given the authority to endure it. But the question remains whether there is a court reporter’s fault in the legal sense if he did so. According to many years of tradition, it was believed that calling a person prematurely a criminal, a journalist violates the principle of the presumption of innocence and, therefore, should be held accountable. However, an in-depth analysis of this problem, conducted in the Chamber of Information Disputes, led to another solution. A journalist does not belong to the category of persons who are authorized to restrict the rights and freedoms of citizens (in comparison, for example, with a prosecutor or a police officer). It means that he cannot influence the human right to be presumed innocent by legal means - the investigation and the court do not depend on his statements. Hence, further, he does not encroach on the presumption of innocence, but only publicly expresses a judgment about the character of his material.

However, the legislation still stands on guard for the honor and dignity of citizens, namely, they are attacked by the reporter who is soon to sentence. Even if the suspect did indeed commit a crime, but this has not yet been recognized in court, he can initiate the initiation of a libel case (under criminal law) or defamation of honor and dignity (under civil law). Experienced professionals have developed strict canons of behavior, having precisely defined the range of their competence. In the ethical declaration of the Judicial Reporters Guild (a group of journalists constantly covering court and pre-trial proceedings) it is written: “Sentences of guilt or innocence ... only the court passes. At the same time, the presumption of innocence in the legal sense of the word does not interfere with the journalistic investigation. We do not pass sentences, but we can press charges if we have convincing grounds for this. ”

Journalistic investigation of cases in which investigators or judges are at the same time is not prohibited by law and is not limited to any special framework. Moreover, there are excellent opportunities for cooperation between the media and law enforcement agencies - in the form of information exchange, mutual moral support, and even constructive partner criticism. There are no bans on coverage of the activities of the courts, including the critical reviews about it and its products - decisions and decisions. Therefore, at least the claims of some representatives of the third (judicial) authorities to be beyond the reach of journalistic analysis look strange. The editors of one of the Far Eastern newspapers lost the case on the suit of the judge. As the journalists of Izvestia, who stood up for their colleagues, told, the reason for the litigation was an article in which the correspondent criticized the legality and validity of the sentence, which was chaired by the author of the statement of claim. According to the claimant, the journalist did not have the right to review the court decision. But he didn’t do it, because he didn’t have the authority, but only expressed his opinions and assessments, which is guaranteed to him by the Law “On Mass Media”.

A common motive of claims against newspaper workers is pressure on the court, which they allegedly exert by their "inappropriate" publications. Pressure is indeed forbidden. But it should not be confused with objective and evidence-based analysis. В декларации Гильдии судебных репортеров давлением признается «такое комментирование хода следствия или суда, которое ведется неграмотно, без всяких аргументов, без предоставления слова обвинению или защите для изложения позиций обеих сторон. Недопустимо распространение о судьях, лицах, ведущих следствие или участвующих в деле, порочащих сведений, если они не имеют отношения к предмету публикации».

По особой формуле строится освещение судебных заседаний. В зале заседания распоряжается судья. Председательствующий на процессе, в частности, имеет право объявить его закрытым (по основаниям, предусмотренным в законодательстве), причем данное ограничение может распространяться как на все материалы дела, так и на их часть. Тогда представители прессы не будут допущены в зал заседания. Однако в принципе судопроизводство в России ведется открыто, а приговор всегда объявляется публично. Это означает, что если слушание не было объявлено закрытым, то никаких ограничений для журналистов вводиться не должно. Подчеркнем, что решение принимает судья, а не, скажем, охрана, которая лишь обеспечивает соблюдение не ею установленного порядка. Поэтому такие эксцессы, как выдворение корреспондентов по инициативе милиции или изъятие у них аппаратуры, что случается время от времени, в корне противоречат закону.

За судьей закреплены и другие исключительные права. По его распоряжению запрещается фото- и киносъемка или видеозапись – и тогда в запасе у репортера остается блокнот. Делать записи и зарисовки на бумаге разрешается при всех обстоятельствах. В прессе некоторых стран судебные репортажи иллюстрируются рисунками, а не снимками: съемка в процессе слушаний там запрещена. Заметим попутно, что не стоит пытаться обмануть служителей Фемиды, делая скрытую съемку. Мало того, что вас удалят из зала и сорвется редакционное задание. Эти действия почти наверняка будут истолкованы как неуважение к суду, за что полагается еще более жесткое наказание. С другой стороны, именно суд может принять решение о демонстрации скрытой записи (фото-, видео- и др.) каких-либо событий, распространение которой в других условиях запрещено и которая, стало быть, обречена безмолвно пылиться в журналистском архиве.

Последнее замечание. Если в зале заседаний оспорить позицию судьи журналист фактически не в состоянии, то это не означает, что он беззащитен перед произволом по отношению к себе. Во-первых, существует механизм обжалования неправомерных действий и решений, нарушающих права и свободы граждан, – обжалования как в административном, так и в судебном порядке. Во-вторых, в распоряжении корреспондента находится мощное оружие гласности: как и всякий факт бюрократизма, закрытие дверей суда перед общественностью заслуживает критической публикации.

Право на ответ и опровержение. Законодательство предусматривает достаточно надежные механизмы самозащиты граждан в отношениях с прессой: ответ на публикацию, опровержение и возмещение морального вреда и убытков.

At the first acquaintance with the regulatory documents it may seem that these mechanisms work according to a simple scheme. However, putting them into action is associated with a number of circumstances, and inattention to the conditions of their use is fraught with additional troubles for journalists. Answer – наиболее мягкая форма разрешения спора между редакцией и гражданином или фирмой. Согласно Гражданскому кодексу, право на ответ имеют граждане и юридические лица, в отношении которых СМИ опубликованы сведения, ущемляющие их права или охраняемые законом интересы. Имеются в виду личные неимущественные права и нематериальные блага (в противном случае речь шла бы о возмещении убытков). Эти понятия охватывают жизнь и здоровье, достоинство и доброе имя, деловую репутацию, личную и семейную тайну, право авторства и др. По сути дела, любое «прикосновение» к личности, а также к практике юридического лица способно возбудить у персонажа публикации обиду и желание оспорить высказывания автора. Этому активно помогают сами журналисты, с их небезобидными привычками. Чего стоит, например, неистребимое желание покаламбурить в связи с фамилией персонажа: из имени, которое стало как бы вторым «я» человека, конструируются клички, отнюдь не всегда приличного свойства.

Главный практический вопрос для редакции – стоит ли помещать на полосе или в эфире контрмнение обиженного человека. Лучше всего снять конфликт без публикации: внимательно выслушать разгневанного оппонента, принести ему извинения и т.п. Но если он все-таки настаивает на ответе? Редакции разрешается отказать в его опубликовании по многим основаниям: если «неугодные» сведения уже были ею опровергнуты, если заявитель обратился к ней спустя более года со дня распространения этих сведений, к тому же в тексте ответа должно быть точно указано, какие конкретно сведения имеются в виду, когда и как они были распространены, то есть предполагается соблюдение ряда формальных требований. В некоторых случаях редакция категорически обязана отклонить ответ: если он представляет собой злоупотребление свободой массовой информации, противоречит вступившему в силу решению суда или является анонимным. Но это особые обстоятельства, и встречаются они не так часто. В большинстве же ситуаций приходится делать собственный выбор: да или нет.

По нашему мнению, «да», как правило, предпочтительней, даже когда заявитель не абсолютно строго соблюдает формальные требования. Возможность полемики заложена в демократической природе прессы, и, кстати сказать, законодательство о СМИ пронизано идеей плюрализма. Тем более важно помнить об этом в связи с деликатной сферой личных интересов. Авторитет редакции только укрепится, если она будет демонстрировать свою открытость для разнообразных суждений и уважение к правам человека. Помимо нравственно-этических соображений есть и вполне прагматические доводы в пользу «да». Отказ в ответе подлежит обжалованию в судебном порядке, и нет гарантий, что редакция выиграет дело.

Вот противоречивая ситуация. Закон «О средствах массовой информации» допускает, что право на ответ возникает, в частности, при распространении не соответствующих действительности сведений. Но, по мнению специалистов, надо руководствоваться Гражданским кодексом, где называется только ущемление прав и интересов[14]. Значит, следуя букве закона, при искажении в публикации фактов редактор не обязан публиковать ответ. Однако для суда распространение недостоверных сведений как раз служит одним из оснований принять исковое заявление об опровержении или клевете. Фактические неточности лучше устранять незамедлительно, да еще и с извинениями перед пострадавшей стороной. Для этого в очередном выпуске газеты или телепрограммы надо дать рубрику «Поправка», появление которой снизит вероятность потенциального конфликта.

В качестве ответа печатается текст, представленный гражданином или организацией, за их подписью (в эфире разрешается дать им возможность зачитать текст). Это очень существенное обстоятельство. Редакция не признает за собой нарушение закона – она лишь идет навстречу обиженной стороне. Опрометчиво поступают в тех СМИ, где добровольно помещают рубрику «Опровержение» и снимают авторскую подпись. Тем самым они не предотвращают апелляцию к суду, а наоборот – создают для нее дополнительные основания. Наконец, предоставляя слово оппоненту, редакция сохраняет шансы отстаивать свою позицию. Во-первых, начиная со следующего после ответа выпуска СМИ разрешается помещать «ответ на ответ». Во-вторых, уже одновременно с ответом можно опубликовать редакционный комментарий к нему. Остается только взвесить – поможет это делу или раздует ненужный скандал.

The work of journalists with a refutation почти полностью совпадает с правилами публикации ответа. Однако не только последствия публикации опровержения, но и основания для него другие. Необходимо, чтобы в материале СМИ присутствовало сразу несколько признаков: сведения распространены (практически это значит – опубликованы), они не соответствуют действительности, они порочат честь, достоинство и деловую репутацию (для юридического лица – только деловую репутацию, поскольку честь и достоинство не могут принадлежать организации). Список признаков больше, чем необходимо для ответа, а сфера действия меньше. Из нее очевидным образом исключаются обоснованные критические выступления прессы – ведь они соответствуют действительности, даже если наносят ущерб достоинству или деловой репутации. В то же время порочащей признается лишь та информация, которая и недостоверна, и содержит утверждения о нарушении законодательных или моральных норм. Скажем, фельетонист построил материал в форме пересказа снов, которые якобы видит губернатор области: ничего зазорного в том, что человеку по ночам являются сновидения, разумеется, нет. Сообщение о привычках человека – пусть и необычных, и неприятных для окружающих, но укладывающихся в рамки морали– не относится к категории порочащих сведений.

However, the area of rebuttal is not so narrow. Along with factual information, it absorbs the assessment that the press gives to the facts of behavior or the person’s personality (firm, organization).

Some room for maneuver gives journalists the interpretation of the concept of "information". By definition of the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation, it means “approval” in this context. It means that the fragments of the publication that contain journalistic assumptions and conjectures cannot be the subject of the proceedings. It is useful to be aware of this detail, and to use it skillfully — sometimes on it, as on the last hope, the journalist’s self-defense holds. In some situations, even a single word (“it seems,” “thinking,” “apparently,” etc.) turns out to be salutary, warning readers that the editors are not insisting on the final version of events. The same goes for publishing rumors. The Law “On Mass Media” prohibits their dissemination under the guise of reliable information - it means that it is necessary to mention that it is rumors that appear in the material, and not facts verified by the journalist.

As practice shows, the media often loses court cases, and they have to publish a refutation. This is an unpleasant, but in a material sense, not a devastating operation. However, according to the Civil Code, it can be accompanied by compensation for losses and non -pecuniary damage to the plaintiff, which can make huge gaps in the media budget. Let's pay attention to the fact that the Law “On Mass Media” provides for the compensation of moral (non-pecuniary) damage only, there is no mention of losses. This means that this rule applies only to a citizen, since a legal entity cannot experience physical and moral suffering, which constitutes moral harm. Losses as a result of the negligent actions of journalists are borne by any firm or organization. They are understood, in particular, expenses that are incurred or must be incurred to restore the violated right, loss or damage to property, as well as lost income (loss of profits). True, the plaintiff is faced with the task of showing exactly what kind of losses he bears in connection with the dissemination of unreliable information: for example, additional funds were spent on advertising the slandered company, disrupted planned transactions, etc.

Sometimes compensation for non-pecuniary damage is estimated by the plaintiff in ridiculous, symbolic figures - 1 ruble, and in other cases rises to several million. However, the amount claimed by the victims will not necessarily be confirmed by the court - he himself decides how much moral damage will cost the editorial board. According to established practice, compensation is usually correlated with the real incomes of the media (for example, income from a single edition of the edition), but this rule is not backed up by law, and there is no guarantee that the lost case will not be borne by the editor for an unbearable financial burden.

In conclusion, a brief reference about those instances in which conflicts between the press and citizens or organizations can be considered. The majority of illegal decisions and actions related to the establishment of the media and the restriction of access to information are appealed by them to the courts of general jurisdiction — regional people's, urban, regional ones. Here, as a rule, the majority of lawsuits against journalists are also considered. Economic disputes, in which the editorial board is involved, are settled in arbitration courts. In Russia, there is no institution of the press ombudsman, which has been introduced in many European countries, but there is a similar structure - the Trial Chamber for Information Disputes. It bears the status of a state body under the President of the country, but is not part of the presidential administration. At the same time, it is not included in the official judicial system, in particular, it does not have a mechanism for enforcing its decisions - they are executed voluntarily by those individuals and organizations to whom they are addressed. The competence of the Chamber also includes the ethics of mass information exchange. Any interested party, including individual citizens, can essentially apply to it. The activities of the judicial system are combined with the activity of public foundations and organizations specifically created to protect information rights and freedoms: the Glasnost Defense Foundation, the Commission on Freedom of Access to Information, the National Press Institute, etc.

to the begining

Comments

To leave a comment

Creative activity of a journalist

Terms: Creative activity of a journalist