Lecture

General characteristics of the game in animals

As already noted (see part 2, ch. 1), the juvenile (or game) period of development of behavior can only be said about the young of higher animals, in which the development of behavior takes place before puberty in the form of play activity. Therefore, only about such animals and will be discussed here. In other animals - and the overwhelming majority of them - the individual development of behavior is limited to the processes of maturing innate forms of behavior, obligate and facultative learning described in the previous chapter, as well as the elementary forms of exploratory behavior.

Animal games have long attracted the attention of researchers, but nevertheless they are still poorly understood. Formulated at different times, views on this issue can be basically united around two concepts that were first put forward in the last century, on the one hand, G. Spencer, and on the other - K. Groos.

In the first case, the game activity of the animal is considered as the expenditure of some kind of "excess energy", as a kind of surrogate for the "natural application of energy" in the "real actions" (Spencer). This view, which accentuates the emotional aspects of the game, received a new incarnation in the modern concepts of “vacuum activity”, a vivid example of which is “idle actions” described by Lorenz, i.e. instinctive movements performed in the absence of corresponding key stimuli. True, Lorenz pointed to significant differences between the game and the "vacuum activity".

The main drawback of the interpretation of the game in animals as the realization of “excess energy” is, as S. L. Rubinstein noted, in the separation of this form of activity from its content, in its inability to explain the specific functions of the game in animal life. At the same time, the ethological concept of “idle actions” sheds some light on possible elements of the endogenous motivation of the game behavior of animals.

In the second case, we are dealing with a “purely functional” interpretation of gaming activities as exercises in especially important spheres of life. Following Groos, the game was viewed as a "practice for adult behavior" and C. Lloyd-Morgan. He emphasized that the game allows the young animal to practice vital actions without risk, because in these conditions mistakes do not entail harmful consequences: during the game, hereditary forms of behavior can be improved even before the defects of behavior are fatally “brought to trial by natural selection ".

It is clear that a full-fledged theory of animal games should include a synthesis of the positive aspects of the concept of both these directions. Nevertheless, to date, some researchers strongly deny the functional significance of the games of young animals for the formation of adult behavior, while others, on the contrary, see the full significance of games in the latter. At the same time, a negative assessment is often accompanied by a reference to the possibility of maturing adult behavior without exercise in the juvenile age.

Thus, the well-known Dutch zoopsychologist F. Boytendijk, speaking out against Groos’s concept, argued that the game is only important for the player directly, leading him to a positive emotional state, but not for his future. Instinctive forms of behavior, according to Boytendijk, mature independently of the exercises; in the same place where there is an exercise in some actions, this is not a game. Criticism of the concept of Buytendijk was given by D. B. Elkonin, pointing out, in particular, that Boytendijk underestimated the orienting-research function of the game.

The value of the game for the formation of adult animal behavior is also denied by some other zoopsychologists. A number of scientists leave the question of the exercise function of the game open (for example, P. Marler and V. Hamilton), others see in the game a certain “para-activity” (A. Brownlie), non-specific “imaginary activity” (M. Meyer-Holzapfel), “Self-reinforcing activity” (D. Maurice), “patterns” of adult behavior (C. Loizos), etc. Meyer-Holzapfel calls curiosity one of the criteria for play behavior. It is also significant that the game takes place only when genuine instinctive actions are not performed. The timbre also upholds the “autonomy” of game activity and considers it possible to give only a negative definition of games as behavioral acts, the function of which, he writes, cannot be directly understood either from action or from their results.

Nevertheless, Timbrek assumes that the game increases the alternatives of individual behavior in relation to the surrounding world, and by incorporating elements of learning, it is possible that new systems of behavior in the motor sphere are formed. Following Lorenz, Tembrock compares the game with the "idle action." The game is also “unfinished”, but these actions are determined by powerful internal motivation and are carried out in rigid, non-variable forms, while the game in many cases depends on external factors, in particular on the game objects, and acts in very labile forms. At the same time, there are search (preparatory) phases and own key stimuli for game behavior, as is the case with typical instinctive behavior. The game is often aimed at "biologically neutral objects", which the rest of the time do not attract the attention of the animal. In contrast to similar instinctive actions (for example, fighting or catching prey), game actions are performed repeatedly and tirelessly. As a result, Timbrok considers games to be a kind of instinctive actions with independent motivational mechanisms.

A different opinion is shared by the Swiss scientist G. Hediger. Emphasizing the optional nature of the game, he points out that, unlike all instinctive actions to perform game actions, there are no special effector formations, there are no special “game organs”. However, he refers to the work of another Swiss scientist-physiologist V.R. Hess, who found that there is no “game center” in the cat's brain, while for all instinctive actions such centers can be detected by introducing microelectrodes.

Based on research conducted jointly with his staff, A. D. Slonim suggests that within certain periods of postnatal development, instinctive reactions are caused by subthreshold external stimuli or even only by internal stimuli arising in the neuromuscular device itself. The “spontaneous” activity that arose in the latter case manifests itself in gaming activity. Although this activity does not depend on the external environment, it can be enhanced by conditioned reflexes or external influences (for example, temperature).

Returning to the question of the functional significance of the game, it should be noted that at present most researchers still believe that the game serves as a preparation for adult life and the accumulation of relevant experience through exercise, both in the sensory and motor spheres. In the latter case, the information that arrives directly from effector systems, reafferently, ensures their “adjustment”, the development of an optimal “mode of action”.

In this regard, it is appropriate to mention the assumption expressed by Elkonin that the game prevents excessively early fixation of instinctive forms of activity and develops all afferent-motor systems necessary for orientation in difficult and changing conditions. As a juvenile exercise, Thorpe also views the game. According to Thorp, the game serves to acquire the skills of animals and to get acquainted with the world around them. Thorpe attaches particular importance to the manipulation of objects.

As for direct experimental evidence of the value of the game for the formation of adult behavior, such evidence was obtained by a number of researchers. Back in the 1920s, for example, it was established that the sex games of young chimpanzees are a necessary condition for the ability to mate in adults (research by G. Bingham). In the future, this fact has received repeated confirmation. F.Bich, as well as the well-known monkey behavior researcher G.V. Nissen, even expressed the view that in monkeys sexual behavior depends primarily on learning, but not on instinctive principles. Similarly, joint games prepare young monkeys for future herd life (studies by G. Harlow, S. J. Suomi, and others).

It was experimentally possible to prove that males also learn to perform actions related to reproductive behavior through sexual games. This especially applies to grooming and preparing for mating. The mating itself is formed from completely innate movements and gaming experience gained by young males in the course of their interaction with sexually mature females.

Of great interest are the data obtained by Nissen together with K. L. Chau and J. Semmes. These experimenters prevented the chimpanzee cub from playing with objects without restricting the movements of the hands, in particular the hands and fingers. Subsequently, the possibility of using hands, as well as coordination of their movements, turned out to be very imperfect. The monkey sharply lagged behind its normal peers in their ability to grip and grope, was not able to localize the tactile stimulations of the body surface with the hand (or she did it extremely inaccurately), and in general all hand movements were extremely clumsy. It is characteristic that, unlike other monkeys, she did not know how to cling to her attendant, she did not stretch her arms towards him. Even the search for monkeys, which was so characteristic of monkeys, was an important form of their communication.

The variety of interpretations of the games of young animals is largely due to the fact that the game activity of animals is a complex set of very diverse behavioral acts, which together comprise the content of the behavior of a young animal at the stage of ontogenesis immediately preceding puberty. Therefore, Fabry proposed the concept that the game is in its essence an evolving activity covering most of the functional areas. With this understanding of the game as a developing activity, a synthetic approach is reached to the problem of the game activity of animals, which unites all the points noted above, and at the same time it becomes obvious that the game activity fills the main content of the behavior development process in the juvenile period. A game is represented not by some special category of behavior, but by a combination of specifically juvenile manifestations of ordinary forms of behavior. In other words, the game is a juvenile (one might say, “preadult”, i.e., “before the adult state”) phase of behavioral development in ontogenesis.

For this reason, it is impossible to agree with the above-mentioned views of the game as a “para-activity”, “imaginary activity” or “pattern” of adult behavior. Such interpretations cannot be justified either by references to the imperfection, incompleteness or inferiority of play actions, to the absence of a corresponding biological effect, for all this indicates that we are dealing here with processes of developing behavioral acts or, which is the same thing, with actions that have not yet reached their full development. The game is not a “sample” of adult behavior, but the behavior itself in the process of its formation.

This, of course, does not mean that the formation of the behavior of an adult animal is accomplished only by playing or that the game replaces other, earlier components of the ontogeny of behavior. On the contrary, in higher animals, whose young are actively playing, in the juvenile period the factors of early ontogenesis described in the previous chapter remain and continue to act, but in the juvenile period they often merge, usually in a transformed form, with playful behavior. At the same time, of course, the behavior of the pups is improved in “non-player” situations, as was the case at the pre-game stage of ontogenesis.

It is also important to emphasize that, as will be shown later, in the course of the game, not entirely adult behavioral acts, but the sensorimotor components that make them, develop and improve. In general, play activity, carried out on an innate, instinctive basis, itself serves to develop and enrich the instinctive components of behavior and contains elements of both obligate and facultative learning. The ratio of these components may be different in different specific cases. But in general, it can be said that the game activity ends a long and extremely complex process of formation of behavioral elements, originating from embryonic coordination and leading through postnatal maturation of congenital motor coordination and accumulation of early experience to the formation and improvement of motor coordination of the highest level. This last stage of development of motor activity is represented by the game.

In addition, the game performs a very important cognitive role, especially due to its inherent components of elective learning and exploratory behavior. This function of the game is expressed in the accumulation of extensive individual experience, and in some cases this experience can accumulate "for the future", "just in case" and find application much later in emergency life situations.

Improvement of motor activity in animal games

Manipulation games

Having recognized the game as a developing activity, it is now necessary to clarify what exactly and how it develops, what the game activity introduces to the behavior of the animal. It is most convenient to do this when considering manipulation games, i.e. games of young animals with objects. As an example, take the game manipulations of young predatory mammals (observations of Fabri and Meshkova).

The first actions of the game type appear in young animals only after an epiphany. In a little fox, for example, this period will come on the 12th day after birth. It has already been said that before this, all its manipulative activity is reduced to just a few actions, and the manipulations produced by the two forelimbs (without the involvement of the jaw apparatus) are represented by only one, the most primitive form, and there are still no actions done by only one front paw.

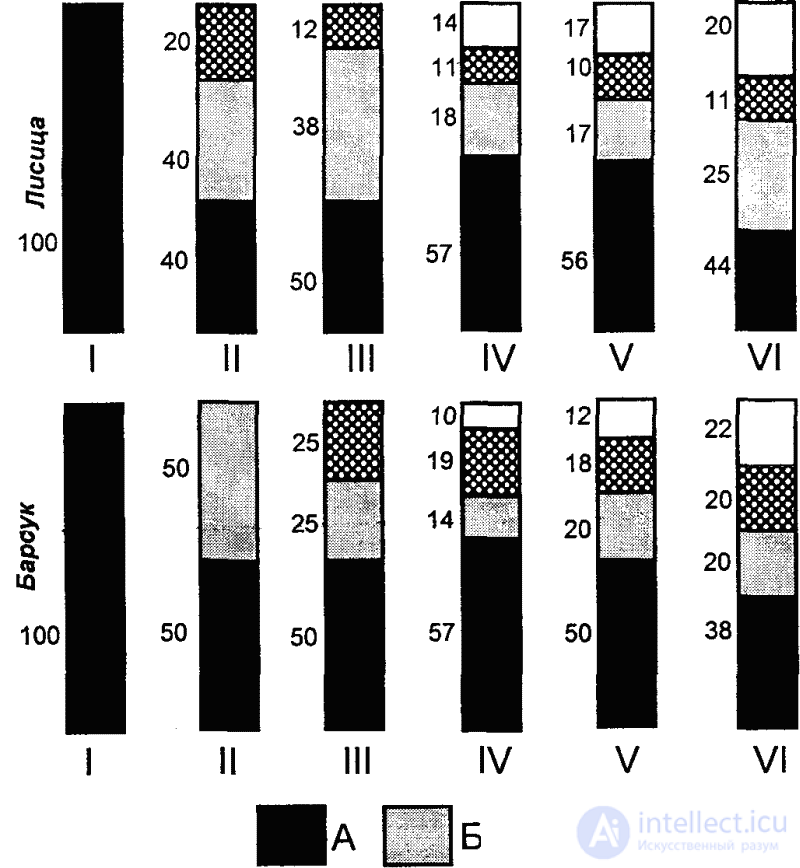

When, after opening the eyes and then coming out of the nest soon after, the cub begins to play (in canines at the age of 16–23 days), this leads to a genuine leap in the development of the motor sphere, and the number of forms of manipulation increases dramatically (in a fox up to 28), and the number of objects to manipulate.

There are "toys" - the objects of the game. New activities of the cub are no longer associated with sucking, and their distinguishing feature is the large general mobility of the young animal. The foxes touch, grab, bite off everything that comes across to them, drag everything they can in their teeth from place to place, slam small objects, clamping them in their teeth and shaking their heads from side to side. Typical and frequently performed forms of game handling of objects are also prying the object with the nose (often with a subsequent tossing), holding the object partially or wholly in the teeth (in the first case the object rests with one end on the substrate), sticking the object with the mouth or nose on the front limbs that lie motionless on the substrate (the object is resting on them, like on a stand), scooping up the object with its front paws to itself, pressing the object to the body, lying on its back, with simultaneous obkus nyvaniem, nudging and moving on the surface of the body nose or forelimbs. In other cases, the object is pressed by the limbs to the substrate, and at the same time part of the object is pulled up or to the side with teeth. Digging movements, etc., are often produced.

For the first time, there are manipulations performed by only one forelimb. This is touching, stroking, pressing down objects with a single brush, touching objects with the edge of a brush with retracting or leading movements of the limb, pulling objects with a paw and pinching them with bent fingers or hooking them over the edges with claws.

As we can see, in the juvenile period of ontogenesis, there is a significant enrichment of the motor activity of a young animal (Fig. 22). At the same time, however, new forms of manipulation are built primarily on the basis of the original, pre-game forms and represent only a modification of the primary forms of activity on a large number of new, different-quality objects. In other words, qualitative changes in the behavior of the cub, coupled with the onset of play activity, are the result of the development of pre-game forms of manipulation, maturation of the motor and sensory components of this primary manipulation.

Так, например, у лисенка возможность взять разные небольшие предметы ртом заранее дана предшествующим хватанием соска, возможность трепания (резкими движениями головы из стороны в сторону) — расталкиванием головой собратьев, приминания и перемещения «игрушек» к субстрату и по нему — соответствующими движениями головой и конечностями в области соска. Даже такие сравнительно сложные формы игрового обращения с предметами, как их обкусывание с одновременным удерживанием передними конечностями на субстрате или удерживание субъекта по рту с одновременным его подталкиванием передними конечностями (лежа на животе или боку), можно без труда вывести из таких первичных пищевых движений, как поиск соска, его захватывание и сосание с одновременным упором в живот матери. Из этих двигательных элементов вырастает и отбрасывание или подбрасывание схваченного предмета в сторону или вверх и т. д.

В целом мы находим во всех игровых действиях (включая и вновь появившиеся действия одной конечностью) проявления расширения и усиления первичных дополнительных функций ротового аппарата и передних конечностей, что стало возможным в результате физического развития детеныша, позволяющего ему вступить в более разнообразные отношения с окружающим миром. Таким образом, по отношению к предыгровым манипуляциям игры молодых животных с предметами представляют собой новые формы манипулирования, которые, однако, состоят из прежних, но функционально усиленных и расширенных моторных элементов. Поэтому игру молодых животных и необходимо признать развивающейся деятельностью.

Следует отметить, что это соотношение между первичной двигательной активностью и последующей имеет место не только в сфере дополнительных функций, о которых до сих пор говорилось, но и в сфере главных функций основных эффекторных систем. Так, вместо одного пищевого объекта (молоко) появляется разнообразная пища, различная по своим физическим качествам. Такую пищу можно употребить лишь после предварительной обработки. И если раньше было достаточно одного пищевого действия — сосания, то сейчас молодому животному приходится овладевать многими новыми формами обращения с пищевыми объектами, тренировать и совершенствовать соответствующие движения, что и происходит во время манипуляционных игр.

Если обратиться к нашему примеру — лисенку, то первоначально главная (пищевая) функция ротового аппарата представлена сосанием. Вскоре после прозревания лисята начинают облизывать пищевые (как и непищевые) объекты (в возрасте до 21 суток), а затем есть твердую пищу. Соответствующие движения челюстного аппарата берут свое начало от его первичных хватательных движений. Поскольку, однако, первичные хватательные движения челюстного аппарата не служили для поедания захватываемого объекта (сосок не откусывается и не съедается), то мы имеем здесь дело со сменой функций.

Как способ приема жидкой пищи появляется лакание, причем характерно, что первоначально лакающие движения весьма напоминают первичные сосательные: язык складывается желобком, через который жидкость втягивается. Постепенно эти движения превращаются в подлинное лакание.

Итак, мы видим, что значение игровой активности в формировании моторных компонентов поведения определяется глубокими качественными преобразованиями в двигательной сфере с проявлениями расширения и интенсификации функции, отчасти субституции (переход некоторых дополнительных функций от ротового аппарата к конечностям или наоборот), а иногда и смены функции. Все это происходит в результате упражнения и совершенствования немногих изначальных моторных элементов, причем количественные изменения последних приводят к появлению качественно новых форм манипулирования.

Биологическая обусловленность манипуляционных игр

До сих пор мы рассматривали манипуляционные игры только на примере одного вида хищных млекопитающих (лисицы), у которого, однако, эта активность развита слабее, чем у многих других представителей этого отряда, особенно если иметь в виду медведей, енотов и кошек. У этих животных отмеченные качественные преобразования еще более разительны, поскольку они обладают намного более мультифункциональными передними конечностями, чем псовые. Большинство манипуляций выполняется лисицей, подобно другим псовым, только челюстным аппаратом, так как псовые обладают олигофункциональными («олиго» — мало) конечностями, специализированными к быстрому длительному бегу. В этих условиях ротовой аппарат сохраняет в большой степени дополнительные двигательные функции, которые, например, у медведей присущи передним конечностям. Поэтому субституционные преобразования, равно как явления расширения, усиления и смены функции, выступают в манипуляционных играх медвежат значительно интенсивнее и разнообразнее, чем у лисят (Фабри).

По-иному проявляется в играх специализация передних конечностей у барсука. По данным Мешковой, у барсучат эти конечности больше участвуют в игровых действиях, чем у детенышей псовых. Это связано со специализацией барсука к норному образу жизни и питанию относительно малоподвижной пищей. В жизни взрослых барсуков большую роль играют такие формы манипулирования, как рытье и транспортировка грунта передними конечностями, сгребание ими подстилочного материала и т. д. Эти действия и развиваются в играх барсучат с предметами.

Весьма однообразными являются манипуляционные игры у детенышей копытных. Немногочисленные манипуляции, выполняемые головой или передними конечностями, состоят в толкании (носом), нанесении ударов, кусании, скребущих и роющих движениях. Совершенно отсутствуют манипуляции, выполняемые совместно челюстным аппаратом и конечностями или одновременно обеими передними конечностями. Это, как и вообще весь характер игры у детенышей копытных, отражает специфическую обусловленность игр образом жизни этих животных. Предельная специализация двигательного аппарата к основной, опорно-локомоторной, функции сходит к минимуму способность манипулировать.

Диаметрально противоположная картина наблюдается у обезьян. У этих животных грудные (передние) конечности наименее специализированы, и их дополнительные функции получили предельное развитие среди млекопитающих (и вообще всех животных). Соответственно этому мы находим в играх молодых обезьян не только намного больше двигательных элементов, чем у других животных, но и качественно новые формы, о которых еще пойдет речь.

Видотипичные особенности поведения, обусловленные образом жизни, достаточно четко проявляются уже в пределах одного семейства. Так, в играх лисят появляются типичные для лисиц внезапные высокие прыжки («мышкование» взрослых особей), как и элементы характерных для взрослых особей приемов борьбы и охоты (специфические формы подкарауливания, подкрадывания, нападения, умерщвления жертвы и т. п.). С другой стороны, по Мешковой, игры щенков динго более однообразны, чем игры лисят. В них преобладает длительное преследование друг друга, в чем воплощается такая характерная особенность поведения взрослого динго, как охота гоном (стремительным преследованием жертвы).

Особенно заметно на игровой активности, в частности на сроках появления манипуляционных игр, сказывается степень зрелорождения детенышей, но сущность процесса от этого не меняется.

Ювенильное манипулирование и взрослое поведение

Двигательный репертуар взрослого животного, как нам уже известно, формируется путем обрастания и дополнения инстинктивной, врожденной основы поведения видотипичным индивидуальным опытом, т. е. путем облигатного научения. Теперь можно добавить, что у высших животных это облигатное научение совершается в ювенильном периоде, перед половым созреванием, в форме игровой активности. При этом имеется в виду, что, как и в раннем постнатальном периоде, облигатное научение включает в себя также факультативные компоненты или сочетается с таковыми.

Этот процесс, как только что было показано, знаменуется модификацией первичных доигровых двигательных элементов. В ходе игры из них формируются, упражняются и совершенствуются существенные компоненты поведения взрослого животного. Это выражается и в том, что с возрастом все усложняющееся манипулирование приобретает все больше видотипичных черт.

Модификация доигровых двигательных элементов происходит по мере того, как предметная деятельность молодого животного распространяется на все новые объекты, в связи с чем растет моторно-сенсорный опыт животного, устанавливаются все более важные связи с биологически значимыми компонентами среды, в том числе с сородичами (о формировании группового поведения см. ниже).

При таком понимании игры как развивающейся деятельности становится ясным, почему игровые действия выполняются «не всерьез». Ведь «серьезные» действия являются завершением этого развития. В полной мере выявляется и биологический эффект игр, в данном случае манипуляционных, который выражается в построении, совершенствовании, «отработке» моторных (и сенсорных) компонентов поведенческих актов. Подчеркнем еще раз, что игры молодых животных — это не действия, аналогичные таковым взрослых животных, а сами эти «взрослые действия» на стадии их формирования из более примитивных морфофункциональных элементов.

Формирование общения в играх животных

Совместные игры

Групповое поведение у высших животных также формируется в большой степени в процессе игры. Эту роль выполняют совместные игры: под ними следует понимать такие игры, при которых имеют место согласованные действия хотя бы двух партнеров. Совместные игры встречаются только у животных, которым свойственны развитые формы группового поведения.

Конечно, общение формируется не только в ходе совместной игровой активности детенышей. Достаточно указать на то, что ритуализованные формы поведения, эти важнейшие компоненты общения, в полной мере проявляются и у таких животных, которые с момента рождения выращивались в полной изоляции и не имели никакой возможности общаться, а тем более играть с другими животными. К генетически фиксированным, инстинктивным формам общения относится и взаимное стимулирование (аллеломиметическое поведение). Что же в таком случае формируется в сфере общения у высших животных лишь в результате игровой активности? Чтобы ответить на этот вопрос, необходимо и в данном аспекте проанализировать игровую активность молодых животных как развивающуюся деятельность, учитывая при этом, что и общение является одной из форм деятельности животных.

Cooperative games are performed mostly without items. As in the manipulation games, the features of the animal's lifestyle are manifested in them. Thus, among the rodents, the young guinea pigs lack game play, and their games are limited to joint jumps and butting, which serves as an "invitation" to the game. Skirmishes in these animals always lead to damage, but the first fights appear only simultaneously with genuine sexual behavior, that is, on the 30th day of life. In the woodchuck, for example, the leading manifestation of play activity is precisely the game struggle: young animals often “fight” for a long time, rising to the hind limbs and clasping each other with their forelegs. In this position, they are shaking and pushing. They often observe game flight, while general-purpose games are rare among young marmots.

The game wrestling among predators is widespread. Hunting is dominated by hunting games (besides general mobility), which often turn into a game struggle. The German ethologist K. Wustehube sees this as preparation for the struggle against large, powerfully resisting prey. Like other mammals, the pursuer and the pursued in such games often change roles. In bear cubs, the game struggle is expressed in the fact that the partners push and “bite” each other, clasping their front paws, or strike each other. There are also joint jogging (or swimming in a race), playing “hide and seek”, etc. It is interesting to note that, as field observations of bear behavior researcher P. Krotta have shown, brown bear cubs play in natural conditions less often than other predatory cubs. Crott explains this by saying that from the very beginning the mother does not bring the bear cubs food and they have to spend a lot of time searching for him, so they often have no time to play.

German ethologist R. Shenkel succeeded on the basis of two years of field research conducted in Kenya, to trace the formation of game behavior of lions from the first days of their life. Their joint games (like other feline cubs) consist primarily of sneaking up, attacking, stalking, and “fighting,” with partners changing roles. Schenkel stresses that the game of the cubs serves to shape adult behavior, but initially it consists only of diffuse motor elements. This is another confirmation of the concept of the game as a developing activity.

Relationships that develop between partners in the course of cooperative games, especially when playing a game, take on a most hierarchical character. Elements of antagonistic behavior and subordination were established in the games of many mammals. True, these subordinate relationships are not always directly develop into those in adults.

In canine hierarchical relations begin to form at the age of 1–1.5 months, although the corresponding expressive poses and movements appear during the game earlier. So, in foxes already on the 32–34th day of life, there are quite pronounced “attacks” on fellows with signs of imposition and intimidation. Already at the beginning of the second month of life, coyotes appear hierarchically. The timbre has shown that, unlike adults, relations of domination and submission arise in canine pups based on un-ritualized aggressive communication. Consequently, the ritualized forms of communication, although appearing in ontogenesis rather early, begin to fulfill their role much later.

As for the non-ritualized game communication of young animals, in particular canine, then probably all their movements also have a signal value. So, for example, “beating” of a partner is not only a manifestation of “brute” physical strength, it bears signs of un-ritualized demonstration behavior, being a means of mental influence on a partner, intimidation. The situation is similar with the attack on a partner, etc.

In contrast to the joint non-manipulation games considered so far in joint manipulation games, animals include in their joint actions some objects as a game object, therefore communication between partners is partly mediated in such games. Such games play a large communicative role, although such objects can simultaneously serve as a replacement for a natural food object (for predators, victims).

As an example of a joint manipulation game, the joint actions of three young ferrets with an empty tin can described by Wüstehube can be cited. Being accidentally dropped into the basin of the washbasin, this bank was then repeatedly dumped by them there, which produced the corresponding noise effect. When the animals were given a rubber ball instead of a can, the ferrets didn’t play with it that way, but subsequently they found another solid object - a faience stopper with which they resumed the same “noise” game.

In the wild four-month-old piglets, the German ethologist G. Fredrich once observed a lively joint game with a coin: the piglets sniffed and crushed it with "piglets", pushed, grabbed their teeth and threw it up, sharply raising their heads. Several piglets participated in this game at the same time, and each of them tried to master the coin and play with it in the described manner. Fredrich also watched the joint games of young boars with rags. Like puppies, piglets snapped their teeth at the same time with the same rag and pulled it in different directions. The “winner” either ran away with a rag, or continued to play on her own, beat it, and so on.

In such “trophy” games, the elements of demonstration behavior also clearly stand out, and an imposing effect is achieved with the help of an object - a “mediator”, more precisely, by demonstrating its possession. Of course, “challenging”, seizing, taking away an object play no less a role, as well as an immediate “test of strength”, when animals, clutching at the same time at an object, pull it in different directions.

Game alarm

The coherence of gaming partners is based on reciprocal innate signaling. These signals serve as key stimuli for gaming behavior. These are specific poses, movements, sounds that alert the partner about the readiness for the game and “invite” him to take part in it. For example, in a brown bear, according to Crott's field observations, the “invitation” to the game is that the bear is slowly approaching a possible gaming partner, shaking his head to the left and right, then falls to the ground and very carefully clasps it with its front paws. In canine cubs, the “invitation” to the game is carried out using a special (“game”) manner of approaching the partner, by specifically swinging the head from side to side, by bending down the front part of the body, accompanied by its swinging or small jumps from side to side as viewed by the partner , raising the front paw towards the partner, etc. The “flashing” cub simultaneously has longitudinal folds on the forehead, and the auricles are facing forward. In wyverre, “flirting” occurs through naskakivaniya, light biting and especially jumping up, in monkeys - by naskakivaniya, twitching the tail or hair, slaps, etc.

No less important are the signals that prevent the "serious" outcome of the game struggle, allowing animals to distinguish the game from "not the game." Without such a warning that aggression is “not real,” the game struggle can easily become genuine. These signals are clearly related to the postures and movements of “pacification” in genuine clashes of adult animals, they mainly create a common “game situation”.

Of principal interest is the fact that the signals of “flirting”, “inviting to the game”, in essence, are signals of a genuine aggressive attack, and only in a game situation do they function as “peaceful”. This shows that in the field of communication, gaming behavior is characterized by phenomena of change of function, just as we noted in relation to the development of motor abilities. Similarly, in game communication, both the phenomena of recombination of innate signals or their elements are detected, the improvement of their combination and application, i.e. the expansion and intensification of the function, as well as the phenomenon of function substitution. There is nothing unexpected, because communication develops with game activity in unity with motor skills.

It is also important to note that communication takes place in animals not only with the help of special signaling movements. On the contrary, it is hardly possible to single out any movements in the behavior of a young animal that would be completely devoid of signal value. Obviously, one can speak only of the different specific weight of the signal component of motor acts. The maximum weight of this component is, of course, in ritualized movements, which are already fully used for communication.

The value of cooperative games for adult behavior

For many species of animals, it has been proved that if the young are deprived of the opportunity to play together, then in the adult state the sphere of communication will be noticeably restrained or even distorted. So, in guinea pigs, this is reflected in the preservation of infantile behavior, even after complete puberty, and in abnormal reactions to relatives and other animals (P. and I. Kunkel). Males of rats need to perform the reproductive function in early game communication with other rats. These games contain the basic motor elements of adult male behavior. In minks, the males learn normal communication with the marriage partner during cooperative games from the age of 10 weeks; Coyote puppies raised without game play showed increased aggressiveness, etc.

Particularly clearly the importance of joint games of the young for the further life of the individual is manifested in monkeys. The disastrous consequences of depriving young monkeys of playing with their peers (or other animals) are convincingly shown by the experiments of many researchers, in particular Harlow and his staff. As in other animals, the resulting disorders are found in adults, primarily in their inability to communicate normally with their own kind, especially with sexual partners, and also in maternal behavior. Describing the role of the game in the development of communication in monkeys, well-known researchers of behavior, primates S. L. Washburn and I. de Vore stressed that the development of normal forms of communication and herd behavior in general is impossible without the game. Young monkeys learn to communicate with each other in "game groups", i.e. groups of young ones playing together, where, according to Ushchburn and de Vora, they "practice the skills and behaviors of adult life."

It is important to note that the function of a partner in the game can successfully be performed by another animal or even a human. This is evidenced, for example, by the fact that with the isolated rearing of young monkeys, who had the opportunity to play only with people, the formation of full-fledged forms of communication takes place without interference. The situation is similar in young predatory mammals, in particular cubs and cubs, when the person raising them or other animals (for example, a dog) replace the natural game partners. All these animals in the future are quite capable of normal communication with their relatives.

Cognitive function of game activity of animals

Game and exploratory behavior

During the game, a young animal acquires a variety of information about the properties and qualities of objects in its environment. This allows us to concretize, refine, and complement the species experience accumulated in the process of evolution in relation to the specific living conditions of an individual.

In the works of a number of reputable scientists, the connection between the game and research activities (Groos, Beach, Nissen, Lorenz, and others) is noted, but there are also differences between these categories of behavior. Refusing to view the game as a "game of nature", allegedly irrelevant to the preservation of the species, Lorenz emphasized its great importance for "research teaching", because during the game the animal treats almost every unfamiliar object as potentially biologically significant and thus seeks out a variety of conditions for existence. This is particularly true, according to Lorentz, of such “curious creatures” (“Neugierwesen”), like corvids or rats, which, thanks to their highly developed research behavior, have managed to become cosmopolitan. Similarly, the prominent German ethologist O. Köhler pointed out that the game is “almost constant search for trial and error,” with the result that the animal slowly, accidentally, but sometimes and suddenly learns what is very important to him.

However, other experts express the view that the similarity between the phenomena of the game and exploratory behavior is only external and is not significant. This view is held, for example, by Hamilton and Marler. However, no one questioned that the acquisition of information through the game is carried out at least in conjunction with the "actual" research activities. Of course, not every orientation research activity is a game, just as familiarization with others is carried out in a young animal, not only in a playful way. But each game contains a research component to one degree or another.

This applies especially to games with objects, to manipulation games, but again, not all manipulation is a game. (For example, manipulation of food objects during meals or nest-building material during nest construction is not a game.) But manipulating “biologically neutral” objects or biologically significant, but outside their adequate application is nothing more than a game.

It is important to emphasize further that any manipulation, especially gaming, always includes a research component. Moreover, the manipulation of "biologically neutral" items is the highest form of orientation and research activities. On the other hand, without a game, a young animal can become familiar with the properties of only objects that have direct biological significance for it. Game manipulation of objects is particularly stimulated by the emergence of new or little-known objects. The role of novelty of the subject components of the environment in the manipulation was especially emphasized for the monkeys by Voitonis.

The development of motor abilities is always associated with environmental research. It can be said that the ever-increasing acquisition of information about the components of the environment is a function of developing motor activity, the orientation of which in time and space, in turn, is based on this information. It is in this that the unity of the motor and sensory elements of behavior developing in the course of the game finds expression.

At the very least, the research component is represented in games that serve only as a kind of "exercise"; to the greatest extent, where there is an active influence on the object of the game, especially of the destructive order, i.e., in manipulation games. The latter may in some cases acquire the value of genuine "research" games (see below).

Mediated games, in particular “trophy” games, occupy a special place, when, obviously, one can even talk about joint cognition of the game object during joint motor exercises. However, these games still serve primarily as a means of communication between animals and the establishment of certain relations between them, as is the case with other cooperative games. Moreover, it is impossible, of course, to be sure that with the “trophy” games, the partners really perceive the structural changes in the game object as such, because their attention is directed at each other.

Instinctive basics of game learning

At the beginning of postnatal ontogenesis, congenital recognition and imprinting are used for primary orientation and urgent accumulation of the most necessary individual experience for an individual. However, as already indicated, even in the course of a later life, individuals innate recognition and imprinting do not lose their meaning, although, of course, they appear differently. Imprinting, for example, plays an important role in the formation of parental behavior (“reverse imprinting”), but innate recognition acts throughout the life of an individual in various forms as an integral part of instinctive behavior (recognition of key stimuli).

In the juvenile period, as also noted above, the innate components mentioned above mostly merge with the game activity, forming its instinctive basis. At the same time, the accumulation of a purely individual (optional) experience is intertwined with a type-specific, instinctive acquisition of information based on innate recognition.

Врожденное узнавание дает играющему животному прежде всего возможность узнать о пригодности определенного предмета или индивида к включению его в игру, руководствуясь при этом соответствующими ключевыми раздражителями. Последние представляют собой пусковые стимулы партнера или определенные свойства замещающего объекта, воспринимаемые в самом обобщенном виде (например, само движение объекта игры). Так, Лоренц приводит следующие признаки, которыми должен обладать объект охотничьей игры котенка в качестве ключевых раздражителей: маленькое, округлое, мягкое, все, что быстро движется, катаясь или скользя, и, главное, все, что «убегает». И в ходе самой игры с партнером или заменяющим его предметом молодое животное реагирует на ключевые раздражители, управляющие упражнением и развитием соответствующих инстинктивных действий.

Можно, очевидно, сказать, что если иметь в виду упражнение и развитие инстинктивных действий, то молодому животному, по сути дела, «все равно», с чем и кем играть, лишь бы объект игры или игровой партнер обладал соответствующими ключевыми раздражителями.

Если же, наоборот, иметь в виду познавательную ценность игры, то именно эти ключевые раздражители приводят молодое животное к биологически наиболее важным для него компонентам среды и обеспечивают тем самым всестороннее ознакомление с ними. Иными словами, врожденное узнавание является здесь необходимой предпосылкой познания носителей ключевых раздражителей уже на перцептивном уровне. Говоря словами Лоренца, путем игры котенок научается узнавать, «что такое мышь». Речь идет здесь именно о мыши как таковой, а не о совокупности присущих ей пусковых стимулов (маленькое, округлое и т. д.), которые воспринимаются животным как ощущения путем врожденного узнавания.

Расширение функции в игровом познавании

При переходе компонентов доигрового поведения в ювенильный период обогащение и трансформация первичных элементов исследовательского поведения совершаются в процессе игры по тем же закономерностям, что и развитие двигательных и коммуникативных компонентов раннего постнатального поведения.

В качестве примера можно указать на расширение функции в сфере исследовательского поведения у незрелорождающихся млекопитающих, в частности хищных. На начальном этапе постнатального развития детеныша получаемая им в гнезде информация является минимальной. С началом же игрового этапа двигательная активность детеныша претерпевает глубокие преобразования, охарактеризованные выше; начинают функционировать дистантные рецепторы, начинается полноценное общение с матерью и собратьями. Все это коренным образом изменяет и, главное, обогащает воспринимаемую детенышем информацию об окружающей его среде. Наконец, с выходом детеныша из гнезда вновь наступает коренное, на этот раз решающее, изменение его двигательной, коммуникативной и соответственно познавательной деятельности. Все его поведенческие акты выполняются уже в совершенно новых условиях: объектами воздействия являются уже не только материнская особь, собратья и немногочисленные предметы внутри гнезда, но ими становятся прежде всего многие разнокачественные предметы с различной биологической валентностью. А это установление новых связей с компонентами среды обеспечивает поступление мощного потока разнообразной жизненно необходимой информации. Огромную роль играют и появляющиеся в это время индивидуальные игры с предметами, доставляющие молодому животному особенно много разнообразных сведений о потенциально биологически значимых объектах. Именно к этой категории игры относятся в первую очередь и манипуляционные игры с «биологически нейтральными» предметами.

Итак, в ходе онтогенеза все больше расширяется и усложняется познавательная деятельность развивающегося животного, имеет место типичное расширение функции, а поскольку исследовательское поведение после выхода из гнезда обращается на качественно совершенно новые объекты, отчасти можно говорить и о явлениях смены функции.

Высшие формы игровой исследовательской деятельности животных

При всем многообразии форм игры их объединяет большая общая подвижность животного, большое разнообразие производимых им телодвижений и интенсивное перемещение в пространстве (рис. 23). Наиболее ярко это выступает, конечно, в играх, которые носят чисто локомоторный характер, выражаясь в разных формах интенсивного передвижения, или которые направлены на собственное тело (игра с собственным хвостом и т. п.). Однако, как мы видели, и в других категориях игровой активности развиваются прежде всего двигательно-сенсорные координации (например, глазомер) и общие физические способности (ловкость, быстрота, реактивность, сила и т. п.). Одновременно упражняются определенные элементы поведения в функциональных сферах питания, защиты и нападения, размножения и др., совершенствуются и развиваются средства общения, устанавливаются отношения с сородичами, причем иногда в виде иерархических взаимоотношений. При всем этом происходит рекомбинация элементов доигрового поведения, в результате чего формируются и совершенствуются новые проявления видотипичного, инстинктивного поведения на более высоком уровне. Как было показано, игровое поведение направляется ключевыми раздражителями независимо от их носителя, но одновременно животное приобретает жизненно важную информацию об этих носителях, об их внешнем виде и о некоторых их физических качествах (вес, прочность, подвижность и т. п.). Однако в целом при всех рассмотренных до сих пор играх происходит лишь поверхностное ознакомление с компонентами среды, чем и ограничивается познавательный компонент этих игр.

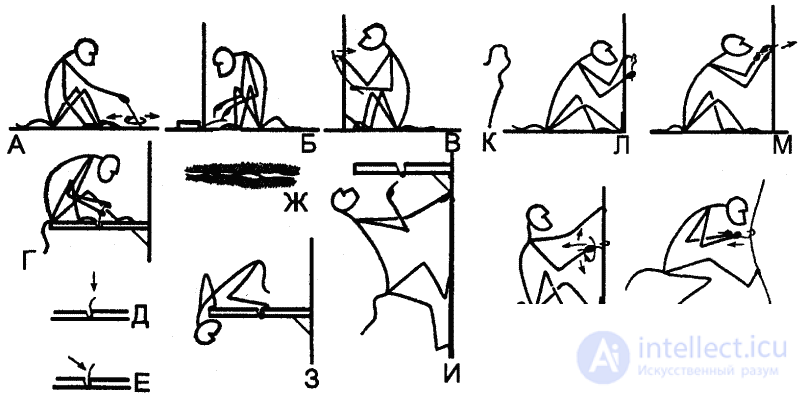

У молодых обезьян (у низших обезьян преимущественно в возрасте 2–5 лет) наблюдаются манипуляционные игры совсем иного рода, которые необходимо признать играми высшего типа (Фабри). В противоположность рассмотренным играм этот тип игры характеризуется прежде всего сложными формами обращения с предметами при незначительной общей подвижности животного: лишь изредка меняя свое местонахождение, животное подолгу и сосредоточенно манипулирует предметом, подвергает его разнообразным, преимущественно деструктивным воздействиям или даже воздействует им на другие объекты. В последнем случае иногда выполняются манипуляции, сходные с орудийными действиями взрослых обезьян (рис. 24).

При подобных сложных играх с предметами совершенствуются высокодифференцированные и тонкие эффекторные способности (прежде всего пальцев) и развивается комплекс кожно-мышечной чувствительности и зрения. Познавательный аспект приобретает здесь особую значимость: животное обстоятельно и углубленно знакомится со свойствами предметных компонентов среды, причем особое значение приобретает исследование внутреннего строения объектов манипулирования в ходе их деструкции. Особое значение приобретает и то обстоятельство, что объектами манипулирования являются чаще всего «биологически нейтральные» предметы. Благодаря этому существенно расширяется сфера получаемой информации: животное знакомится с весьма различными по своим свойствам компонентами среды и приобретает при этом большой запас разнообразных потенциально полезных «знаний». Наличие таких игр у обезьян, несомненно, связано с их отличительными по сравнению с другими животными психическими способностями, в частности их «ручным мышлением», о чем еще пойдет речь.

Таким образом, здесь имеют место подлинные исследовательские, познавательные игры, причем игры высшего порядка. Выполняются эти игры в одиночку. Помимо общего накопления сведений «про запас» такие познавательные игры также прямо и непосредственно готовят животное к взрослому поведению (например, в сфере питания, где дифференцированные движения пальцев играют немалую роль при расчленении плодов, выковыривании семян и т. д.). Включаются такие игры и в сферу общения. Однако так как познавательная функция играет здесь ведущую роль, эти игры приобретают характер самостоятельной сферы поведения с собственным функциональным (специально-познавательным) значением.

Вместе с тем и в этих наиболее сложных проявлениях игровой активности, которые пока удалось обнаружить только у высших приматов, обнаруживается инстинктивная основа, этологические критерии которой вполне соответствуют критериям типичной функциональной сферы (автохтонность, замещение активности, супероптимальное реагирование и т. д.). Это вновь показывает, что общая закономерность единства врожденного и благоприобретаемого поведения сохраняет свое значение в полной мере на всем протяжении онтогенеза, в том числе и на высших филогенетических уровнях.

Comments

To leave a comment

Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology

Terms: Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology