Lecture

Early ideas about the mental activity of animals

Beginning of animal behavior

When studying any form of mental activity, first of all, the question arises about the innate and individually acquired, the elements of instinct and learning in the behavior of the animal. In a broad sense, this is a question about external and internal factors of behavior, about its genetic bases and the embodiment of type-typical behavior in the individual life of an individual, about the motivation of behavior.

Even the ancient thinkers, trying to comprehend the foundations and the driving forces of animal behavior, thought about whether there is some kind of “spiritual principle” in animals, and if so, what is its nature. Thus, Epicurus and his followers, especially Lucretius, answered this question positively, but at the same time defended with certainty the statement about the materiality of such a “soul”. At the same time, Lucretius has already expressed the idea that the expedient actions of animals are the result of a kind of natural selection, because only animals with properties that are useful to them can survive.

The ancient idealist philosophers proceeded from the idea of a kind of original “world of ideas,” a “world mind,” analogous to the concept of God in later church teachings. The offspring of this universal “mind” is the soul of man and animals, which, according to Socrates, connected with the body, is influenced by sensitivity and is guided in its actions by drives and passions. Plato believed that all the behavior of animals is determined by the inclinations. From here there was already only a step to the idea of instincts.

Aristotle, "the greatest thinker of antiquity," as K. Marx called him, was also the first authentic natural scientist among philosophers. Aristotle attributed to man the immortal "rational soul" - the embodiment of the divine spirit. The soul, according to Aristotle, revives perishable matter, the body, but only the body is capable of sensual impressions and inclinations. Therefore, unlike man, endowed with reason, the ability to know and free will, animals have only a mortal "sensual soul." But all the animals with red blood and giving birth to live cubs have the same five senses as humans. The behavior of animals is aimed at self-preservation and procreation, but it is motivated by desires and drives, feelings of pleasure or pain. Along with this, the behavior of animals is determined, according to Aristotle, and the mind represented in different animals in varying degrees. Aristotle considered intelligent animals to be capable of understanding the goal.

Aristotle based his judgments on concrete, and sometimes amazingly accurate, observations (along with, however, anecdotal data). In ants, for example, he noticed the dependence of their activity on external factors (illumination). Regarding a number of animal species, he pointed out their ability to learn from each other; He also described a number of cases of animal sound communication, especially during the breeding season. Perhaps, for the first time, it is in Aristotle that we meet references to experimental data on the behavior of animals. So, he pointed out that after removing the chicks from their parents, they learn to sing differently than the last, and from this they deduced that the ability to sing is not a "gift of nature." Thus, Aristotle already justifies the idea of the individual acquisition of certain components of behavior. This ability to learn individually and to memorize what he learned, Aristotle recognized for many animals and attached great importance to it.

A number of the provisions of Aristotle were further developed in the Stoics' teachings, although in some respects significant differences are found here. The Stoics first appeared the concept of instinct (horme - Greek., Instinctus - lat.). The instinct is understood by these philosophers as innate, purposeful attraction, directing the movement of the animal to the pleasant, useful and leading it from the harmful and dangerous. Chrysippus pointed out in this connection that if the ducklings were bred even by chicken, they nevertheless attracted to their native element — water, where they were provided with food. As other examples of instinctive behavior, Chrysippus referred to nest building and care for the offspring in birds, the construction of honeycombs in bees, and the ability of the spider to weave cobwebs. All these actions are performed by animals, according to Chrysippus, unconsciously, without the participation of reason (which animals do not have), without an understanding of their activities, on the basis of purely innate knowledge. In this case, Chrysippus noted that such actions are performed by all animals of the same species in the same way. Thus, Chrysippus anticipated in a number of essential points the modern scientific view on the behavior of animals.

Similarly, Seneca Jr. believed that animals have innate knowledge of what is harmful to them, for example, innate knowledge of the appearance of predators. At the same time, Seneca also pointed out the uniformity of the forms and results of the inborn activity of animals. By clearly distinguishing between innate and acquired behavior, Seneca denied that animals had a mind or thinking ability. The instinct in the concepts of the Stoics is the imperious call of Nature, which the animal is forced to follow unconditionally, “without reasoning”.

As we can see, already in the works of ancient thinkers, the main problems of animal behavior appeared in all their complexity: the issues of innate and acquired behavior, instinct and learning, as well as the role of external and internal factors of mental activity of animals were discussed. At the same time, those radically different approaches to the study of the psyche of animals were identified, which determined the further scientific search in this area, namely, the materialistic and idealistic understanding of the essence of mental activity.

Pre-evolutionary views on animal behavior (XVIII century)

After a millennial stagnation of scientific thought in medieval times, the revival of scientific creativity began, but only in the XVIII century. The first attempts are made to study the behavior of animals on a solid foundation of reliable facts, obtained as a result of careful observations and experiments. In the middle and end of this century, the works of a whole galaxy of prominent scientists, philosophers and naturalists, who had a great influence on the further study of the mental activity of animals, appear.

Of these, it is necessary first of all to mention the French materialist philosopher, physician by training J.A. Lettri. Lametri held the view that the instincts of animals are a combination of movements that are performed by force, regardless of thoughts and experience. At the same time, he emphasized the biological fitness of instincts, although he could not determine the reason for this. An extremely important feature of the research of Lamettri was a comparative approach to the study of the mental activity of animals. Comparing the psychic abilities of various mammals, as well as birds, fish, and insects, he showed a progressive complication of these abilities towards man. It remains to make only a step towards the idea of the historical development of the psyche. The views of Lamettra, formulated by him on the basis of the then knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the nervous system, subsequently had a great influence on the scientific work of Lamarck.

A large French enlightener, E. B. Condillac, in his Treatise on Animals (1755) specifically addressed the question of the origin of animal instincts. Based on the similarity of instinctive actions with actions performed by habit, Condillac came to the conclusion that instincts originated from rational actions through a gradual deactivation of consciousness: rational behavior turned into a habit, and the latter into instinct.

This interpretation was categorically opposed by Sh. J. Leroy. This naturalist and thinker argued that the series indicated by Condillac should be read in the reverse order. In his “Philosophical Letters on the Mind and the Ability of Animals to Improve”, published by him in 1781, he sets forth the task of studying the origin of reason from the instinct of animals as a result of the repetitive action of sensation and memory exercise. This concept of the development of higher psychic abilities, contrary to church dogmas, was tried to be justified by Le Roy with his own data on the behavior of animals in nature. Le Roy emphasized the importance of field research and persistently argued that the mental activity of animals and especially their instincts can be known only with comprehensive knowledge of their natural behavior and taking into account their lifestyle.

Le Roy saw in the instincts of animals the embodiment of their needs: the need to satisfy the latter leads to the appearance of instincts. Habits, according to Leroy, can be inherited and as a result be included in the natural behavioral complex. Leroy illustrated this with examples of hunting dogs passing on their habits to offspring, or rabbits that stop digging minks after several generations of them lived at home.

We have already mentioned the exceptional role of J.-L. L. Buffon in the formation of zoopsychology as a science. Buffon not only approached the study of the mental activity of animals as a true naturalist, but when analyzing his field observations and experiments, he was able to refrain from anthropomorphic interpretations of animal behavior (unlike many scientists in the late 19th and early 20th centuries). According to his teachings, animals (specifically, mammals were meant) are characterized by various forms of mental activity, in particular sensations and habits, but not an understanding of the meaning of their actions. Equally, animals are able to communicate, but their language expresses only sensory experiences.

Identifying the relationship between the characteristics of the mental activity of animals and their way of life, Buffon advanced the thesis about the relationship of environmental influences with the internal state ("desires") of an animal, seeing in this the determining factor of its behavior. Remarkable are his conclusions about the adaptive value of the psyche, namely that the mental qualities of animals are no less important for the preservation of species than physical qualities. All concepts of Buffon, built on real facts, entered into a single system of natural science created by him and became the first basis of the future science of animal behavior and psyche. It is important for us to note here that a truly scientific study of animal instincts (begun by Buffon before Le Roy) led him to the conclusion that the complex actions of animals are the result of a combination of innate natural functions that give the animal pleasure and habits. Thus, Buffon anticipated the modern understanding of the structure of animal behavior, far ahead of his contemporaries.

The problem of instinct and learning in the light of evolutionary teachings

J. B. Lamarck

By the beginning of the XIX century. the problem of instinct and the related question about the relationship between innate and acquired actions of animals are attracting more and more attention.

Interest in these issues was due to the emergence of the idea of transformationism, the emergence of the first evolutionary theories. The actual task was to identify what is transmitted in inheritance behavior in a “finished form”, which is formed as a result of environmental exposure, what is universal, specific, and what is individually acquired, what is the significance of the different components of behavior in the process of evolution, where the line between human and animal, etc.

According to the metaphysical views on nature that prevailed over the centuries, the animal instincts seemed unshakable, staying in an unchanged state from the moment of their “creation”. The creators of evolutionary theories had to explain the origin of instincts and, using specific examples, show their variability, as they did with respect to the species-like structure of the animal organism.

The first holistic doctrine of the evolution of living nature was formulated at the very beginning of the nineteenth century. Jean Baptiste Lamarck. As you know, Lamarck based his evolutionary concept on the concept of the guiding action of the mental factor. He believed that the external environment acts on the animal body indirectly, by changing the behavior of the animal. As a result of this mediated influence, new needs arise, which in turn entail changes in the structure of the organism through greater exercise of one and the non-exercise of other organs, that is, again through behavior. With all the erroneousness of the general provisions of this concept (the primacy of the psyche as some initial organizing factor, the desire of organisms to "improve", etc.), Lamarck’s great merit is that he pointed to the enormous role of behavior, mental activity in the process of evolution.

Striving to explain the entire historical development of the organic world in a natural-science way, Lamarck argued that even the most complex manifestations of mental activity developed from simpler ones and should be studied in a comparatively evolutionary way. At the same time, he with all certainty denied the existence of a special spiritual principle, not related to the physical structure of the animal (as well as man) and not amenable to natural science. Without exception, all mental phenomena Lamarck recognized as closely related to material structures and processes and therefore considered them quite knowable through experience, following the general path of natural science knowledge of the world.

Lamarck attached particular importance to the connection of the psyche with the nervous system. In contrast to the concepts of psychophysical parallelism, which exist among a number of modern ethologists, Lamarck strongly argued for the functional connection of the psyche with the nervous system, the dependence of mental activity on nervous activity, the dependence of mental evolution on evolutionary transformations in the nervous system. We can rightly say that Lamarck laid the foundations of comparative psychology, comparing the structure of the nervous system with the nature of the mental activity of animals at different levels of phylogenesis.

From these positions Lamarck approached the problem of instinct. “… .The instinct of animals,” he wrote, “is an inclination that attracts, evoked by sensations based on their needs and compels them to perform actions without any participation of thought, without any participation of will.” [12] At the same time, Lamarck did not consider the instinctive behavior of animals as something once and for all initially given and unchanged. In his view, instincts arose in the process of evolution as a result of prolonged exposure to the body of certain agents of the environment. These directed actions led to the improvement of the entire organization of the animal through the formation of beneficial habits, which were consolidated as a result of multiple repetitions, because such repeated execution of the same movements led to the beating of the corresponding nerve paths and more and more easily passing through them the corresponding nerve impulses (“fluids ", In the terminology of Lamarck).

So, according to Lamarck, the inclination identical to instinct “stands in connection with an organization transformed by habits in a favorable direction for it, and is excited by impressions and needs driving the individual’s inner sense and giving it a chance to send — in connection with the requirement of the current inclination — a nerve fluid to subject muscles. " [13] As noted by Academician V.L. Komarov, Lamarck understood under fluids not something mystical, but quite a material principle, close to the modern understanding of energy. "... The habit of exercising one or another organ or one or another part of the body to meet again and again the resurgent needs," continued Lamarck, "makes for a nervous fluid ... movement in the direction of the organ associated with so frequent use of it is so easy that this habit It becomes as if an integral natural property of an individual. " [14] Needs create habits (i.e., determine the process of learning), habits turn into inclinations that animals “cannot withstand, in which they themselves cannot make any changes. From here, their habitual actions and their private inclinations, to which the name of instinct is given, originate . ” This is how Lamarck imagined the relationship between instinct and learning: “the beginning of instinct in animals” is the origin of instinctive actions through lifelong modification of motor activity.

It is necessary to add that, according to Lamarck, "the tendency of animals to preserve habits and to repeat the actions associated with them ... then spreads in individuals through reproduction or reproduction, preserving the organization and arrangement of parts in the reached state, so that the same tendency already exists in new individuals before they start exercising it. ” [16] Такая передача инстинктов от поколения к поколению «без заметных отклонений будет продолжаться до тех пор, пока не произойдет перемены в условиях, существенных для образа жизни». [17] В этих словах особенно отчетливо выражено представление об определяющей роли условий среды в эволюции инстинктивного поведения. Конечно, сегодня нам известно, что Ламарк ошибался, полагая, что переход индивидуально приобретенных в наследственно закрепленные формы поведения возможен путем многократного повторения выученных (или видоизмененных) движений, что привычки могут непосредственно обусловить генетические изменения организации животного организма.

Итак, Ламарк видел в инстинктах животных не проявления какой-то таинственной сверхъестественной силы, таящейся в организме, а естественные реакции последнего на воздействия среды, сформировавшиеся в процессе эволюции. Приспособительный характер инстинктивных действий при этом также является результатом эволюционного процесса, так как постепенно закреплялись именно выгодные организму компоненты индивидуально-изменчивого поведения. С другой стороны, и сами инстинкты рассматривались Ламарком как изменчивые свойства животного. Тем самым взгляды Ламарка выгодно отличаются от встречаемых до наших дней воззрений на инстинкт как на воплощение неких сугубо спонтанных внутренних сил, обладающих изначально целесообразной направленностью действия.

Что же касается индивидуально-изменчивых компонентов поведения животных, их «привычек», навыков, то Ламарк и здесь исходит из материалистических предпосылок, доказывая, что происхождение привычек обусловлено механическими причинами, лежащими вне организма. И хотя Ламарк был не прав, полагая, что сохраненные привычки видоизменяют организацию животного, но в его общем подходе к этой проблеме можно усмотреть правильное понимание ведущей роли функции по отношению к форме, поведения — по отношению к строению организма.

Не давая здесь общей оценки эволюционному учению Ламарка, не касаясь недостатков и исторически обусловленных ошибок этого учения (изначальная целесообразность в природе, в частности в мире животных, гармоничность процесса развития, лишенного противоречий, и др.), необходимо, однако, подчеркнуть трудно переоценимую роль этого великого естествоиспытателя как основоположника материалистического изучения психической деятельности животных и развития психики в процессе эволюции.

К. Ф. Рулье

В середине XIX в. в России страстно и последовательно отстаивал исторический подход к изучению живой природы выдающийся ученый того времени, один из первых эволюционистов, профессор Московского университета К. Ф. Рулье. В те годы в естественных науках все большее распространение получали реакционные теории, и вопросы психики и поведения животных трактовались с идеалистических и метафизических позиций, преимущественно с точки зрения церковного учения. Психическая деятельность животных постулировалась как нечто раз и навсегда данное и неизменное; в их нравах и инстинктах усматривалась беспредельная, непостижимая мудрость Творца, все предусмотревшего и создавшего извечную гармонию в природе.

В этих условиях засилья реакции Рулье решительно и обоснованно выступал против представлений о сверхъестественной природе инстинкта. Подчеркивая, что инстинкты необходимо изучать наравне с анатомией, физиологией и экологией животных, Рулье доказывал, что они являются естественной составной частью жизнедеятельности животных. Это особенно важно, если учесть, что в трудах того времени инстинкты, как и вообще поведение животных, трактовались в отрыве от среды обитания и образа жизни последних. В противоположность упомянутым тео- и телеологическим «объяснениям» Рулье усматривал первопричину происхождения психических качеств и особенностей животных во взаимодействии организма с условиями жизни.

The origin and development of the instincts Rule considered as a special case of a general biological pattern, as a result of material processes, as a product of the external world impact on the body. The instinct, according to Rule, is a hereditary reaction formed during the history of a species, developed by living conditions, to certain environmental influences. Specific factors of the origin of instincts Rule saw in the variability, heredity and a gradual increase in the level of organization of the animal in the course of historical development. In an individual life, instincts may change as a result of experience.

Иллюстрируя изменчивость инстинктов, Рулье писал, в частности, что подобно тому, как меняются телесные качества животных, «подобно тому, как скот вырождается, как качества легавой собаки, неупражняемой, глохнут, так и потребность отлета для птиц, почему-либо долгое время не отлетавших, может утратиться: домашние гуси и утки сделались оседлыми, между тем как их дикие родичи — постоянно отлетные птицы. Лишь изредка отбившийся от дома домашний селезень во время сиденья его подруги на яйцах, начинает дичать, взлетывать и прибиваться к диким уткам; лишь изредка такой одичавший селезень отлетает осенью с своими родичами в теплую страну и следующею весной опять покажется на дворе, где вывелся». [18]

Как перелетный инстинкт, так и нерестовое поведение рыб Рулье пытается проанализировать, опираясь на достижения естествознания его времени. Стремясь к полноценному естественноисторическому объяснению причины перелета птиц, он полагал, что птицы в свое время («когда на нашей планете начали слагаться климаты») начали выбирать себе наиболее благоприятные местности. Молодые птицы «и теперь отлетали бы от нас только в то время, когда голод, холод и нужда принудили бы их к этому, и полетели бы по тому направлению, по которому постепенно уменьшаются невыгодные для их жизни условия…». [19] Но старые птицы «помнят, как отлетали они прежде… знают, когда наступит срок для заблаговременного отлета… хотя неблагоприятные для них условия еще и не показывались». [20] Следовательно, в таком сложном явлении, как мифации птиц, Рулье усматривал сочетание и врожденных и благоприобретаемых компонентов, видового и индивидуального опыта. Интересно также отметить, какое значение Рулье придавал при этом передаче опыта от поколения к поколению. Он вообще считал, что у животных «обыкновение, сделавшееся в отце и матери естественною потребностью, отразится и на детях, как отражаются на них вообще привычки и наклонности родителей». [21]

Оценивая зоопсихологические исследования Рулье, необходимо иметь в виду, что в его время (как, впрочем, и впоследствии) термином «инстинкт» часто прикрывали незнание истинных причин поведения животных. Сам Рулье говорил о том, «что инстинкт в большей части случаев — злоупотребляемое словцо, что за ним кроется вопрос, на который наука не нашла еще нужного объяснения…». [22]

Поэтому Рулье стремился при каждом употреблении этого термина наполнить его конкретным содержанием, полученным в результате полевых исследований или экспериментов, делая при этом упор на выявление роли и взаимодействия факторов среды и физиологических процессов.

Именно такой комплексный анализ поведения животных, стремление по возможности полнее выявить определяющие его экологические и исторические факторы и выдвинули труды Рулье на ведущее место среди естествоиспытателей середины прошлого века.

Ч. Дарвин

С победой эволюционного учения Ч. Дарвина в естествознании прочно утверждается мысль о единой закономерности развития в живой природе, о непрерывности органического мира. Сам Дарвин уделял большое внимание вопросам эволюции психической деятельности животных и человека. Им был написан фундаментальный труд «Выражение эмоций у человека и животных», а также ряд специальных работ по поведению животных. Для «Происхождения видов» Дарвин написал специальную главу «Инстинкт». О значении, которое Дарвин придавал изучению инстинктов, свидетельствует уже тот факт, что наличие их у человека и животных как общего свойства он рассматривал как одно из доказательств происхождения человека от животного предка.

Дарвин воздерживался давать развернутое определение инстинкта, но все же указывал, что имеет при этом в виду такой акт животного, который выполняется им «без предварительного опыта или одинаково многими особями, без знания с их стороны цели, с которой он производится». [23] При этом он с полным основанием отмечал, «что ни одно из этих определений не является общим». [24]

Ссылаясь на видного исследователя поведения животных первой половины XIX в. Фредерика Кювье (брата знаменитого зоолога и основателя палеонтологии позвоночных Жоржа Кювье), Дарвин сравнивает инстинкт с привычкой и указывает на ряд общих черт их проявления в противоположность сознанию. Но одновременно он предостерегает, что «было бы большой ошибкой думать, что значительное число инстинктов может зародиться из привычки одного поколения и быть наследственно передано последующим поколениям». [25]

Происхождение инстинктов Дарвин объяснял преимущественным действием естественного отбора, закрепляющего даже совсем незначительно выгодные виду изменения в поведении животных и накапливающего эти изменения до образования новой формы инстинктивного поведения. Дарвин стремился показать, «что инстинкты изменчивы и что отбор может влиять на них и совершенствовать их». [26]

Свою концепцию Дарвин сформулировал следующим образом: «Едва ли какой бы то ни было из сложных инстинктов может развиться под влиянием естественного отбора иначе, как путем медленного и постепенного накопления слабых, но полезных уклонений. Отсюда, как и в случае с органическими особенностями, мы должны находить в природе не постепенные переходы, путем которых развился каждый сложный инстинкт, — это можно было бы проследить только в ряде прямых предков каждого вида, — но должны найти некоторые указания на эту постепенность в боковых линиях потомков или, по крайней мере, мы должны доказать, что некоторая постепенность возможна, и это мы действительно можем доказать». [27] В подтверждение того, что происхождение даже весьма сложных форм инстинктивного поведения животных можно объяснить действием естественного отбора, Дарвин подвергает, в частности, обстоятельному анализу гнездовой паразитизм кукушки, «рабовладельческий инстинкт» некоторых видов муравьев и «самый удивительный из всех известных инстинктов — строительный инстинкт пчелы». [28]

The action of "one common law that determines the development of all organic beings, namely reproduction, change, experiencing the strongest and the death of the weak," [29] Darwin shows in many other examples of the behavior of wild and domestic animals. The role of heredity in the process of evolution of instinctive behavior, he illustrates with such facts as, for example, smearing a nest of clay with South American and British thrushes or immuring females in hollows in the hornbills of Africa and India.

Exercises and habits, that is, individual learning, Darwin, as already noted, did not attach any significant significance to the historical process of the formation of instinctive behavior; He referred, in particular, to the highly developed instincts of working individuals of ants and bees, unable to reproduce and, consequently, transfer the accumulated experience to offspring. “The peculiar habits inherent in working or barren females, no matter how long they exist, of course, could not affect the males and breeding females, which only give offspring,” [30] wrote Darwin. “And it surprises me,” he continued, “that so far no one has taken advantage of this demonstrative example of asexual insects against the well-known teachings about inherited habits that Lamarck advocates.” Darwin admitted the possibility that only "in some cases habits and exercise or organ non-exercise also have their influence." [31]

Darwin was wrong when Leibnizky recognized Natura non facit saltum as the only criterion for the development of nature, applying this principle to instincts in equal measure to the structure of organisms. But, defending the idea of the interdependence of processes in living nature and proving their material essence, Darwin showed that the mental activity of animals is subject to the same natural-historical patterns as all other manifestations of their life activity.

In this respect, it is very important that Darwin gave a well-grounded natural-science explanation of the expediency of animal instincts. As with the characteristics of the structure of the organism, natural selection preserves, according to Darwin, useful changes in innate behavior and eliminates harmful ones. These changes are directly related to morphological changes in the nervous system and in the senses, because specific behaviors are determined by the structural features of the nervous system, which are inherited and subject to variation, like all other morphological features. Thus, the expediency of instincts is the result of the material process - natural selection. Of course, this fundamentally contradicted the theological views on the essence of the psychic and its initial immutability, in particular the postulate on the expediency of instincts as manifestations of divine wisdom.

Darwin was of the opinion that “there is a certain interaction between the development of mental abilities and instincts, and that the development of the latter involves some inherited brain modifications.” [32] The progress of mental abilities, according to Darwin, was due to the fact that some parts of the brain gradually lost their ability to respond to sensations "in a certain, uniform, i.e. instinctive manner." [33] At the same time, Darwin believed that the instinctive components dominate more in animals than the phylogenetic rank of the latter is lower.

Today, after more than a hundred years after these statements by Darwin, we cannot agree with such an opposition of the main categories of mental activity. The very division of the latter into “uniformly” performed and changeable components is conditional, since in each real behavioral act the rigid and labile elements of behavior appear in a single complex. Accordingly, at each phylogenetic level, these elements, as will be shown, will reach the same degree of development.

Modern understanding of the problem of instinct and learning

In the problem of instinct and learning a large place is occupied by the question of the plasticity of instinctive behavior. This question is very important for understanding not only the evolution of instinctive behavior, but in general all questions concerning the mental activity of animals.

Darwin believed that essentially the plasticity of instincts, resulting from the variability of their congenital morphological bases and giving “material” for the action of natural selection, is sufficient for the evolution of instinctive behavior, and thus behavior in general. Subsequently, many scientists have devoted their efforts to the study of how innate, type-typical behavior is stable or variable, how constant the instincts are, rigid or changeable and can be modified. As a result, today we know that the plasticity of animal behavior is a much more complex phenomenon than it seemed at the time of Darwin, because it is not individual ready movements or their combinations that are genetically fixed and inherited, but response standards within which motor reactions are formed during ontogenesis .

The profound development of the problem of instinct and learning, as noted, was given by V. A. Wagner, especially in his fundamental work Biological Foundations of Comparative Psychology (1910–1913). Based on a large amount of factual material obtained by him in field observations and experiments and covering both invertebrates and vertebrates, Wagner came to the conclusion that the instinctive components of animal behavior arose and developed under the dictation of the environment and under the control of natural selection and that they cannot be considered constant stereotypical. Instinctive behavior, according to Wagner, is a developing plastic activity, modified by external influences.

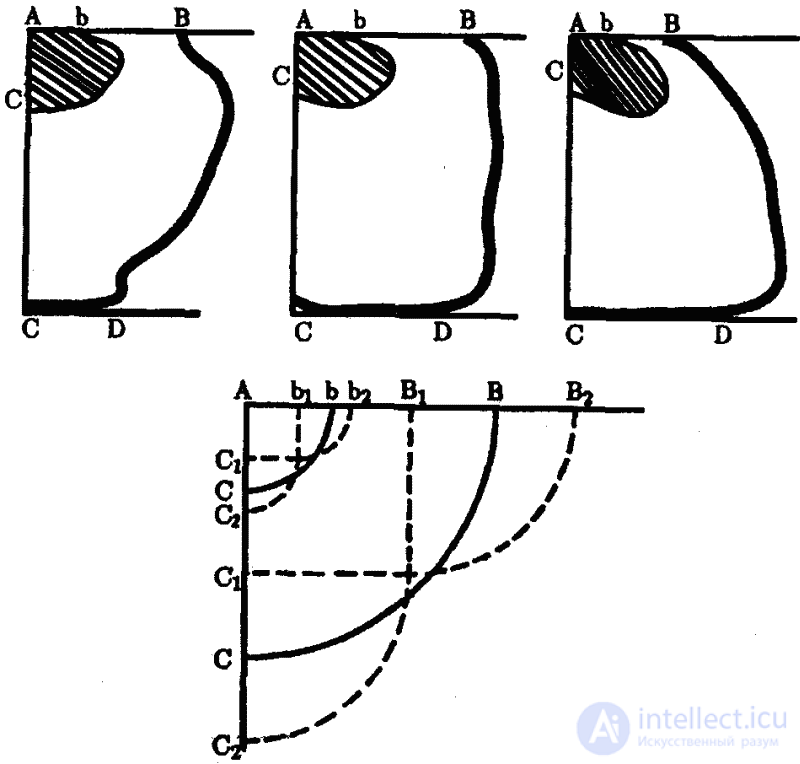

The variability of instinctive behavior was especially convincingly shown by Wagner with examples of the constructive activity of spiders and swallows (Fig. 4). A thorough analysis of these facts led him to the conclusion that the lability of instinctive behavior is limited by a clear type structure, that the instinctive actions themselves are not stable within the species, but the limits of the amplitudes of their variability. Thus, Wagner anticipated one of the main provisions of modern ethology.

Subsequently, other Soviet scientists developed questions about the variability of instinctive behavior and its connection with the processes of learning. Academician L.A. Orbeli analyzed the dependence of the plasticity of animal behavior on the degree of their maturity (see part II, ch. 3). The Soviet ornithologist A. N. Promptov pointed out that the instinctive actions of animals (birds and mammals) always include inherent, very difficult to separate, but extremely essential conditioned-reflex components that are formed in the process of ontogenesis. These components, according to Promptov, determine the plasticity of instinctive behavior. On the other hand, the interaction of innate reactions determined by the type-typical signs of the structure, with conditioned reflexes acquired on the basis of them during their individual life, results in the type-specific features called Promptovy "specific behavioral stereotype".

E. V. Lukina illustrated these provisions of Promptov with examples of the plasticity of the nest-building activity of passerines. So, young females nesting for the first time in their lives, build nests characteristic of their species. However, under unusual conditions, this stereotype is noticeably violated. Thus, the redstart and puff-headed bird, which are double nesting holders, in the absence of hollow trees, arrange their nests under the roots, and the gray flycatcher, curling nests in shelters (crevices of stumps, deep trunks, lagging bark, etc.) may arrange them on horizontal branches or even directly on the ground, etc.

As we see, all these are cases of modification of the nest-building instinct, specifically with regard to the location of the nest. Many examples of replacing nesting material have also been described: artificial materials such as cotton wool, packing chips, gauze, rope, etc. are sometimes used instead of grass, moss, lichen. There are even cases where pied flycatchers built their nests in Moscow parks almost entirely. from tram tickets. Similar data were obtained in special experiments in which the plasticity of instinctive behavior was studied when replacing eggs or nestlings (experiments of Promptev, Lukina, Skrebitsky, Wilke).

In insects, the plasticity of building activity (the construction of caps on the caterpillars Psyche viciella) was thoroughly studied in the laboratories of the Polish zoopsychologist R. I. Wojtuszka in the 1960s (research by K. Gromysh). Another insect, the caterpillar of Autispila stachjanella, also studied the plasticity of instinctive behavior when arranging moves in the leaves and cocoons (M. Berestynskaya-Vilchek's research). Scientists have discovered a large adaptive variability of instinctive actions, especially when repairing buildings of these insects, and in artificial, experimental conditions, these actions may differ markedly from those performed under normal, natural conditions.

Promptov was certainly right when he emphasized the importance of merging innate and acquired components in all forms of behavior. At the same time, his understanding of the plasticity of instincts represents a step backwards compared to the concept of Wagner, who proved that not instinctive actions are inherent, but the framework within which these actions can be performed in a modified form in accordance with the given environmental conditions. The facts cited by Promptov only confirm this.

Refusing the instinctive components of behavior in any intrinsic variability, Promptov believed that plasticity is provided only by the conditioned reflex components of the behavioral act. In reality, we are dealing here with categories of behavioral variability that differ in their magnitude and significance. First, it is the variability of the innate, ie, instinctive, components, which is manifested in the individual variability of the type-typical behavior (within the limits of the hereditarily fixed norm of the type-type response). Examples of such variability are the facts given by Wagner on the nesting activity of the swallows and the mentioned studies of the instinctive behavior of caterpillars. Secondly, the truth is less common, under extreme conditions, type-like, instinctive behavior can be modified quite a lot. Here the role of individual experience is manifested, since it is precisely it that provides a more or less pronounced adaptability to unusual, external conditions beyond the scope of the norm. And finally, there are various individually acquired and therefore the most variable forms of behavior, in which different forms of learning play a dominant role, having, of course, also an instinctive basis and interwoven with innate components of behavior.

The fundamental importance of differences in the variability of instinctive and acquired behavior was thoroughly analyzed by Academician A. N. Severtsov, the founder of evolutionary morphology. In his works “Evolution and Psyche” (1922) and “Main Directions of the Evolutionary Process” (1925), he showed that in higher animals (mammals) there are two types of adaptation to environmental changes: (1) changes in organization (structure and functions of animals) , which occurs very slowly and allows one to adapt only to very slowly gradual environmental changes, and (2) changes in the behavior of animals without changing their organization on the basis of high plasticity of non-hereditary, individually acquired forms of behavior. In the latter case, an effective adaptation to rapid changes in the environment is possible precisely because of a change in behavior. In this case, individuals with more developed psychic abilities will have the greatest success, “inventors” of new ways of behavior, as Severtsov metaphorically put it, in short, animals that can develop the most flexible, plastic skills and other higher forms of individual volatile behavior. It is in this regard that Severtsov considers the importance of the progressive development of the brain in the evolution of vertebrates.

As for the instinctive behavior, it cannot perform such a function due to its low variability (rigidity). But like changes in the body structure of an animal, changes in innate behavior can serve as adaptations to slow, gradual changes in the environment, since they require a lot of time for their implementation.

Recall that this change in innate behavior takes place in the process of evolution based on the individual variability of instinctive behavior. It was in this individual lability of the type-like actions of animals that Darwin was looking for the origin and development of instincts.

Severtsov emphasized that the significance of such a gradual adjustment is no less important than adaptation by changing the individually acquired behavior. “Instincts,” he wrote, “are the essence of species specific, useful for the species as much as these or other morphological signs, and just as constant.” [34] At the same time, Severtsov drew attention to the fact that the ability to learn, to establish new associations depends on a certain hereditary height of mental organization. The actions themselves are not hereditary. In instinctive behavior, he and hereditarily fixed both. Today we can, in confirmation of this thesis of Severtsov, say that the instinctive behavior of animals is determined by the innate program of action implemented in the course of accumulation of individual experience.

Summarizing the above and taking into account the current knowledge about the behavior of animals, it is possible to characterize the relationship and interdependence between the innate and acquired components of behavior and the biological significance of their specific variability as follows.

Constancy, rigidity of instinctive components of behavior are necessary to ensure the preservation and steady performance of the most vital functions, regardless of the random, transient environmental conditions in which one or another representative of the species may find themselves. The innate components of behavior store the result of the entire evolutionary path traversed by the species. This is the quintessence of species experience, the most valuable thing that was acquired during phylogenesis for the survival of an individual and the continuation of the genus. And these generic and genetically fixed programs of actions transmitted from generation to generation should not and cannot easily change under the influence of random, non-essential and non-permanent external influences. In extreme conditions, there are still chances of survival due to the reserve plasticity of instinctive behavior in the form of modification.

In the rest, the realization of the innate program of behavior in the specific conditions of the individual development of the animal is ensured by the processes of learning, that is, the individual adaptation of the innate, type-typical behavior to the particular environmental conditions. For this, extreme flexibility of behavior is necessary, but again the possibility of individual adaptation without losing the essential accumulated during the evolution of the species requires an unshakable foundation in the form of a steady instinctive disposition. Only it gives the animal the ability to respond to itself in any situation with advantage.

Comments

To leave a comment

Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology

Terms: Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology