Lecture

Introductory notes

The evolution of the psyche is part of the overall process of the evolution of the animal world and was carried out according to the laws of this process. Increasing the general level of vital activity of organisms, complicating their relationships with the outside world, in the course of evolution, necessitated ever more intensive contact with an increasing number of subject environmental components, improved movement among these components, and more and more active handling of them. Only such a progressive change in behavior could ensure an increasing consumption of the necessary components of the environment for life, as well as more and more successful avoidance of adverse or harmful effects and hazards. However, all this required a significant improvement in orientation in time and space, which was achieved by the progress of mental reflection.

Thus, movement (primarily locomotion, and subsequently manipulation) was a decisive factor in the evolution of the psyche. On the other hand, without progressive development of the psyche, the motor activity of animals could not be improved, biologically adequate motor responses could not be carried out and, consequently, there could be no evolutionary development.

Of course, mental reflection did not remain unchanged in the course of evolution, but itself underwent a profound qualitative transformation, to which we now proceed. The essential is that which is primary; still a primitive, mental reflection provided only a departure from adverse conditions (as is typical for modern protozoa); the search for the directly non-perceived favorable conditions appeared much later. As we have already seen, such a search is a constant component of developed instinctive behavior.

Similarly, only at high levels of evolutionary development, when objective perception already exists and the sensory actions of animals provide for the emergence of images, mental reflection becomes able to fully orient and regulate the behavior of the animal, taking into account the objectivity of the environmental components. Such reflection is, in particular, of paramount importance for identifying obstacles (in the narrow and broad sense of the word), which, as we have seen, is a necessary condition for the appearance of the most labile forms of individual behavioral adaptation to changing environmental conditions - skills and, in the most highly developed animals , intelligence.

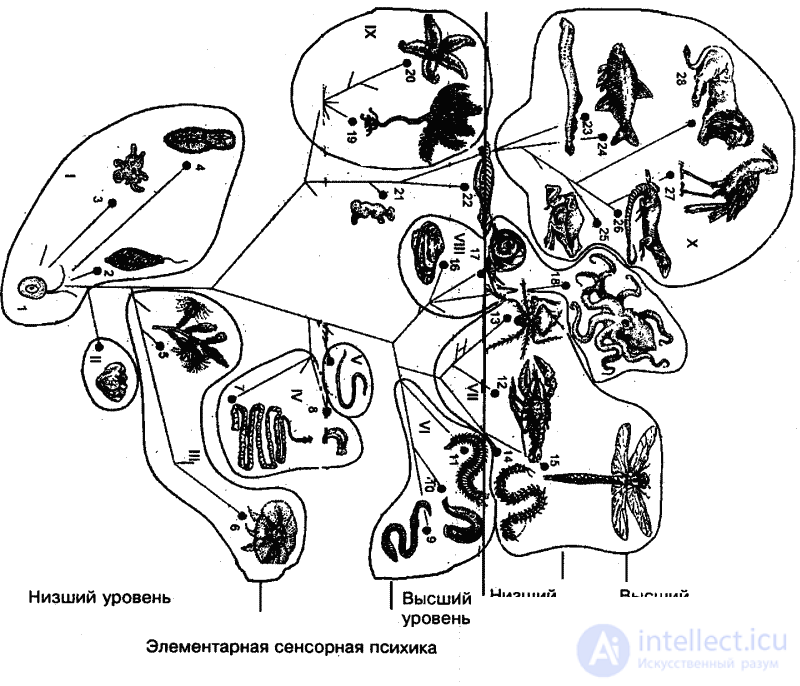

Signs of the most profound qualitative changes that the psyche underwent in the process of the evolution of the animal world, Leontiev based it on the stages of mental development that he singled out. A clear, the most essential boundary lies between the elementary sensory and perceptual psyche, marking the main milestone of the grandiose process of the evolution of the psyche. Therefore, in what follows, we will be based on this division.

An elementary sensory psyche is defined by Leont'ev as the stage at which animal activity “corresponds to a particular individual affecting property (or a combination of individual properties) due to the substantial connection of this property with those influences on which the implementation depends on the basic biological functions of animals. Accordingly, the reflection of reality associated with this structure of activity has the form of sensitivity to individual influencing properties (or a combination of properties), the form of an elementary sensation. ” [48] The stage of perceptual psyche, according to Leontiev, “is characterized by the ability to reflect external objective reality no longer in the form of individual elementary sensations caused by individual properties or their totality, but in the form of reflection of things”. [49] The activity of the animal is determined at this stage by the fact that the content of the activity is highlighted, not aimed at the object of influence, but on the conditions in which this object is objectively given in the environment. “This content is no longer associated with what induces the activity as a whole, but responds to the special influences that cause it.” [50]

However, for our purposes this division is not enough, and therefore it is necessary both within the elementary sensory and perceptual psyche to distinguish significantly different levels of mental development: lower and higher, while allowing for the existence of intermediate levels (Fig. 25). It is important to note that large systematic taxa of animals do not always and not quite fit into this framework. This is inevitable, since within large taxa (in this case, subtypes or types) there are always animals standing at adjacent levels of mental development. This is explained by the fact that the qualities of a higher mental level are always born at the previous level.

In addition, the discrepancies between the psychological and zoological classifications are due to the fact that the morphological features on which the systematics of animals are built do not always determine the characteristics and degree of development of the mental activity of the latter. The behavior of animals is a set of functions of effector organs of animals. And in the process of evolution, it is the function that primarily determines the shape and structure of the organism, its systems and organs.

And only for the second time the structure of effectors, their motor capabilities determine the nature of the animal's behavior, limit the scope of its external activity.

This dialectic process, however, is further complicated by the possibilities of multi-dimensional problem solving (at least in higher animals) and compensatory processes in the field of behavior. This means that if an animal in these conditions is unable to solve a biologically important problem in one way, it, as a rule, has at its disposal other, reserve capabilities. Thus, some effectors may be replaced by others, that is, different morphological structures may serve to perform biologically unambiguous actions. On the other hand, the same bodies can perform different functions, that is, the principle of multifunctionality is implemented. Morphofunctional relationships in coordination systems are especially flexible, especially in the central nervous system of higher animals.

So, on the one hand, lifestyle determines the development of adaptations in the effector sphere, and on the other hand, the functioning of effector systems, that is, behavior, ensures satisfaction of vital needs, metabolism during the interaction of the organism with the external environment. Changes in living conditions give rise to the need to change the former effector functions (or even the appearance of new functions), that is, changes in behavior, and this then leads to corresponding morphological changes in the effector and sensory spheres and in the central nervous system. But not immediately and even not always functional changes entail morphological. Moreover, in higher animals, often purely functional changes without morphological rearrangements are often quite sufficient, and sometimes even the most effective, ie, adaptive changes only in behavior (A. N. Severtsov). Therefore, the behavior in combination with the multifunctional effector organs provides the animals with the most flexible adaptation to the new living conditions.

These functional and morphological changes determine the quality and content of mental reflection in the process of evolution. One should always remember about them, about the dialectic relationship between the way of life (biology) and behavior, when we talk about the primacy of physical activity, animal activity, in the development of mental reflection.

It is appropriate to recall once again that, contrary to the still prevailing view, the innate and acquired behavior are not consecutive steps on the evolutionary ladder, but develop and become complicated together, as two components of one single process. Consequently, there was not and there is no such a position that the lower animals have only one instinct (or even reflexes), which are replaced by higher skills, and the instincts are increasingly disappearing. In fact, as already shown, the progress in individually variable behavior corresponds to the progressive development of precisely instinctive, genetically fixed behavior. Instinctive behavior reaches the greatest difficulty just in higher animals, and this progress entails the development and complication of these forms of learning in these animals.

Here we can, of course, give only the most general overview of the evolution of the psyche, and then only in some of its areas and with few examples, without revealing the whole variety of ways for the development of the psyche in the animal world.

Chapter 1

ELEMENTARY SENSORY PSYCHE

The lowest level of mental development

At the lowest level of mental development is a fairly large group of animals; among them there are also such animals that are still on the verge of the animal and plant world (flagellates), and on the other hand, relatively complex single-celled and multicellular animals. The most typical representatives of the group of animals considered here are the protozoa, on the example of which a characteristic of the lowest level of the elementary sensory psyche will be given here. True, some highly organized protozoa (from among the ciliates) have already risen to a higher level of elementary sensory psyche. In this regard, it should be recalled that the phylogenesis of protozoa proceeded to a certain extent parallel to the development of lower multicellular animals, and this, in particular, was reflected in the formation of the simplest analogues of the organs of such animals. These analogues are called organelles.

Simplest movements

The movements of protozoa are distinguished by a great diversity, and in this type of protozoa there are locomotion methods that are completely absent in multicellular animals. This is a peculiar way of moving amoebas using plasma “transfusion” from one part of the body to another. Other representatives of the simplest, the Gregarines, move in a kind of “reactive” way - by extracting mucus from the back end of the body, “pushing” the animal forward. There are also the simplest, passively floating in the water.

However, most protozoa move actively with the help of special structures that produce rhythmic movements - flagella or cilia. These effectors are plasmatic processes that perform oscillatory, rotational, or wavelike movements. Flagella, long hair-like outgrowths have the already mentioned primitive protozoa, which received their name due to this formation. With the help of flagella, the body of the animal (for example, euglena) is brought into a spiral-shaped translational motion. Some marine flagellates, according to the Norwegian scientist I. Trondsen, rotate when moving around an axis at a speed of up to 10 revolutions per second, and the speed of translational movement can reach 370 microns per second. Other marine flagellates (from the number of dinoflagellates) develop speeds from 14 to 120 microns per second and more. A more complex effector apparatus is the cilia, covering in large numbers the body of the infusoria. As a rule, the ciliary cover is unevenly distributed, cilia reach to different parts of the body of different lengths, form annular seals (membranella), etc.

An example of such a complex differentiation is ciliates from the genus Stylonychia. The peculiar organelles of these animals allow them not only to swim, but also to "run" on a solid substrate, and both forward and backward. It was established that the coordination of these methods and directions of locomotion, as well as their “switching”, is carried out by special mechanisms localized in three centers and two axes of excitation gradients in the cytoplasm.

Flagella and cilia are driven by contractions of the myofibrils, which form filaments, the mionems, corresponding to the muscles of multicellular animals. In the majority of protozoa, they are the main motor apparatus, and there are even those of the most primitive representatives of the flagellate type. Mionemes are arranged in a strict order, most often in the form of rings, longitudinal threads or ribbons, and in higher representatives in the form of specialized systems. So, the ciliates of Caloscolex have special systems for the dead pillars of the membranes, pharynx, hind gut, a number of retractors of certain body parts, etc.

It is interesting to note that, as a rule, the mionems have a homogeneous structure, which corresponds to the smooth muscles of multicellular animals, however sometimes there are cross-striated mionemes comparable to the striated muscles of higher animals. All contractile filaments serve to perform fast movements of individual effectors (in the simplest ones, needle-like outgrowths, tentacle-like formations, etc.). Complicated systems of Miemon allow the simplest to produce not only simple contractile movements of the body, but also quite diverse specialized locomotor and non-locomotor movements.

For those protozoa, which do not have miones (in amoebas, rootgrass, sporozoans, with one exception, and some other protozoa), contractile movements are performed directly in the cytoplasm. So, when moving the amoeba in the outer layer of the cytoplasm, in ectoplasm, genuine contractile processes occur. It was even possible to establish that these phenomena occur every time in the “back” (with respect to the direction of movement) part of the amoeba body.

Thus, even before the appearance of special effectors, the movement of an animal in space is accomplished by contractions. It is the contractile function, the carrier of which is in the simplest mionem, and in multicellular muscles, provided all the diversity and complexity of the motor activity of animals at all stages of phylogenesis.

Kinesis

Locomotion of the simplest is carried out in the form of kinesis - elementary instinctive movements. A typical example of kinesis is orthokinesis - translational motion with variable speed. If, for example, there is a temperature gradient (temperature difference) in a certain area, then the movement of the shoe will be the faster, the farther the animal will be from a place with an optimum temperature. Consequently, here the intensity of the behavioral (locomotor) act is directly determined by the spatial structure of the external stimulus.

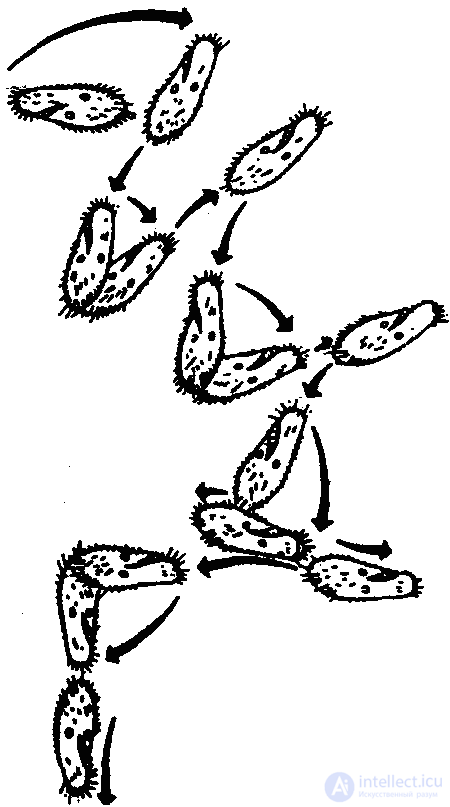

In contrast to orthokinesis, there is a change in the direction of movement with clinokinesis. This change is not purposeful, but has the character of trial and error, as a result of which the animal eventually ends up in the zone with the most favorable parameters of stimuli. The frequency and intensity of these changes (and hence the angle of rotation) depend on the intensity of the (negative) stimulus (or stimuli) acting on the animal. With the weakening of the force of action of this stimulus decreases and the intensity of klinokinesis. Thus, the animal and here responds to the gradient of the stimulus, but not by increasing or decreasing the speed of movement, as in orthokinesis, but by turning the axis of the body, that is, by changing the vector of motor activity.

As we can see, the implementation of the most primitive instinctive movements - kinesis - is determined by the direct influence of the intensity gradients of biologically significant external factors. The role of the internal processes occurring in the cytoplasm is that they give the behavioral act a “first push”, like in multicellular animals.

Orientation

Already in the examples of kines, we have seen that the gradients of external stimuli act at the simplest at the same time as triggering and guiding stimuli. This is especially evident in clinokinesis. However, changes in the animal's position in space are not truly orienting here, since they are non-directional. To achieve the full biological effect of the klinokinetic, as well as orthokinetic, movements need additional correction, allowing the animal to more adequately orient itself in its environment according to sources of irritation, and not just change the nature of movement under adverse conditions.

The orienting elements of the representatives of this type and of other lower invertebrates, which are at this level of mental development, are the simplest taxis. In orthokinesis, the orientoxtaxis orienting component manifests itself in a change in the velocity of movement without changing its direction in the external stimulus gradient. In clinokinesis, this component is called clinotaxis and manifests itself in a change in the direction of motion at a certain angle.

Как мы уже знаем, под таксисами понимают генетически фиксированные механизмы пространственной ориентации двигательной активности животных в сторону благоприятных (положительные таксисы) или в сторону от неблагоприятных (отрицательные таксисы) условий среды. Так, например, отрицательные термотаксисы выражаются у простейших, как правило, в том, что они уплывают из зон с относительно высокой температурой воды, реже — из зон с низкой температурой. В результате животное оказывается в определенной зоне термического оптимума (зоне предпочитаемой температуры). В случае ортокинеза в температурном градиенте отрицательный ортотермотаксис обеспечивает прямолинейное удаление от неблагоприятных термических условий. Если же имеет место клинокинетическая реакция (рис. 26), то клинотаксис обеспечивает четкое изменение направления передвижения, ориентируя тем самым случайные клинокинетические движения в градиенте раздражителя (в нашем примере — в термическом градиенте).

Зачастую клинотаксисы проявляются в ритмичных маятникообразных движениях (на месте или при передвижении) или в спиралевидной траектории плывущего животного. И здесь имеет место регулярный поворот оси тела животного (у многоклеточных животных это может быть и только часть тела, например голова) на определенный угол.

Клинотаксисы обнаруживаются и при встрече с твердыми преградами. Вот пример соответствующего поведения инфузории (туфельки). Наткнувшись на твердую преграду (или попав в зону с другими неблагоприятными параметрами среды), туфелька останавливается, изменяется характер биения ресничек, и животное отплывает немного назад. После этого инфузория поворачивается на определенный угол и снова плывет вперед. Это продолжается до тех пор, пока она не проплывет мимо преграды (или не минует неблагоприятную зону).

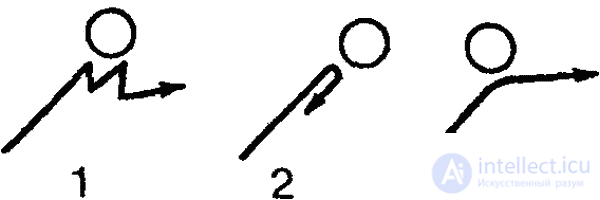

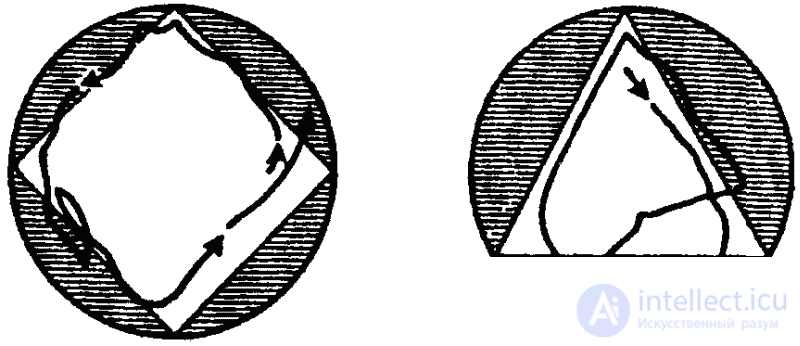

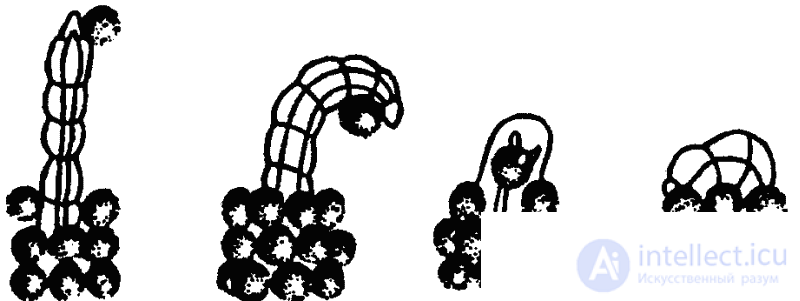

Согласно новым данным (В. Розе), инфузории, однако, не всегда ведут себя подобным образом. Клинотаксисы наблюдаются лишь при встрече с преградой под углом в 65–85° (рис. 27, 1). Если же встреча произойдет под прямым углом, инфузория переворачивается через поперечную ось тела и «отскакивает» назад (рис 27, 2). Если же животное встречается с преградой по касательной, оно проплывает мимо, свернув в сторону (рис. 27, 3).

Клинотаксисы хотя встречаются и у более высокоорганизованных животных, относятся к примитивным видам таксисов. Тропотаксисов у простейших нет, поскольку тропотаксисы предполагают наличие симметрично расположенных органов чувств.

В приведенных примерах описывались реакции простейших (в данном случае инфузорий) на температуру и тактильный раздражитель (прикосновение). Речь шла, следовательно, о термо- и тигмотаксисах, в последнем случае — об отрицательном тигмоклинотаксисе, возникающем в ответ на сильное тактильное раздражение (соприкосновение с твердой поверхностью объекта).

Если же, наоборот, туфелька натыкается не на твердое препятствие, а на мягкий объект (например, растительные остатки, фильтровальная бумага), она реагирует иначе: при такой слабой тактильной стимуляции инфузория останавливается и прикладывается к этой поверхности так, чтобы максимальный участок тела соприкасался с поверхностью объекта (положительный тигмотаксис). Аналогичная картина наблюдается и при воздействиях других модальностей на направление движения, т. е. положительный или отрицательный характер реакции зависит от интенсивности раздражения. Как правило, простейшие реагируют на слабые раздражения положительно, на сильные — отрицательно, но в целом простейшим больше свойственно избегать неблагоприятных воздействий, нежели активно искать положительные раздражители.

Возвращаясь к тигмотаксисам, важно отметить, что у инфузорий обнаружены специальные рецепторы тактильной чувствительности — осязательные «волоски», которые особенно выделяются на переднем и заднем концах тела. Эти образования служат не для поиска пищи, а только для тактильного обследования поверхностей объектов, с которыми животное сталкивается. Раздражение этих органелл и приводит в описанном примере к прекращению кинетической реакции.

Особенностью тигмотаксисной реакции является то, что она часто ослабевает, а затем и прекращается после прикасания к объекту максимальной поверхностью тела: приставшая к объекту туфелька в возрастающей мере начинает реагировать на иной раздражитель и все больше отделяется от объекта. Затем, наоборот, вновь возрастает роль тактильного раздражителя и т. д. В результате животное совершает возле объекта ритмичные колебательные движения.

Четко выражена у туфельки и ориентация в вертикальной плоскости, что находит свое выражение в тенденции плыть вверх (отрицательный геотаксис — ориентация по силе земного притяжения). Поскольку у парамеции не были обнаружены специальные органеллы гравитационной чувствительности, было высказано предположение, что содержимое пищеварительных вакуолей действует у нее наподобие статоцистов [51] высших животных. Обоснованность такого толкования подтверждается тем, что туфелька, проглотившая в опыте металлический порошок, плывет уже не вверх, а вниз, если над ней поместить магнит. В таком случае содержимое вакуоли (металлический порошок) уже давит не на нижнюю ее часть, а, наоборот, на верхнюю, чем, очевидно, и обусловливается переориентация направления движения животного на 180°.

Кроме упомянутых таксисные реакции установлены у простейших также в ответ на химические раздражения (хемотаксисы), электрический ток (гальванотаксисы) и др. На свет часть простейших реагируют слабо, у других же эта реакция выражена весьма четко. Так, фототаксисы проявляются у некоторых видов амеб и инфузорий в отрицательной форме, а инфузория Blepharisma снабжена даже светочувствительным пигментом, но, как правило, инфузории не реагируют на изменения освещения. Интересно отметить, что у слабо реагирующих на свет простейших отмечались явления суммации реакции на механические раздражения, если последние сочетались со световыми раздражениями. Такое сочетание может увеличить реакцию в восемь раз по сравнению с реакцией на одно лишь механическое раздражение.

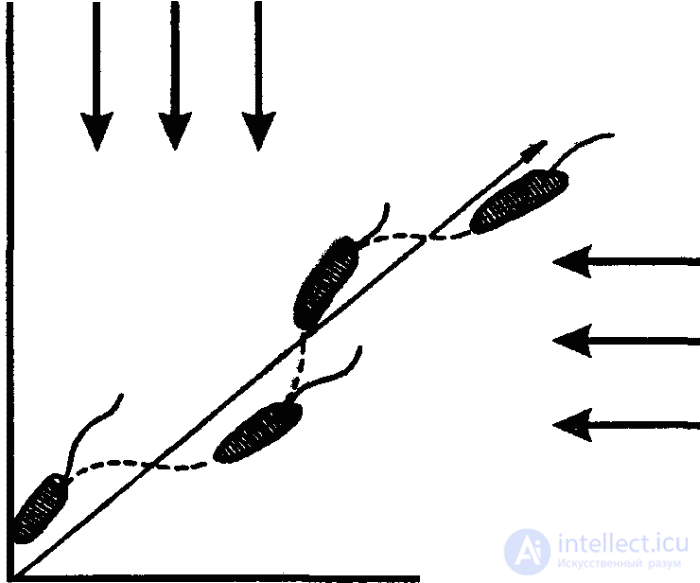

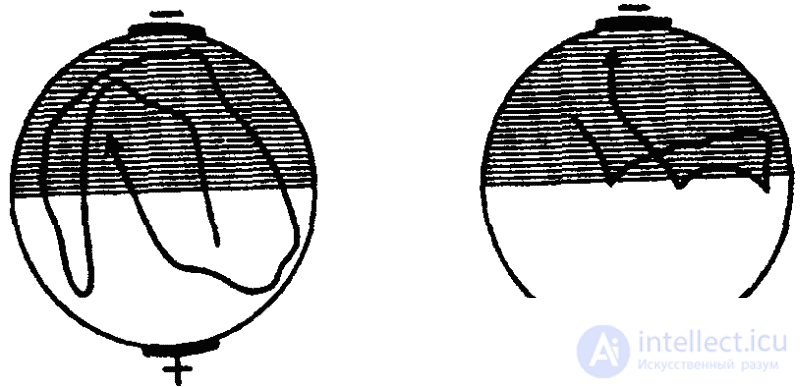

В отличие от инфузорий у многих жгутиковых, особенно у эвглены, положительный фототаксис выражен весьма четко. Биологическое значение этого таксиса не вызывает сомнений, так как аутотрофное питание эвглены требует солнечной энергии. Эвглена плывет к источнику света по спирали, одновременно, как уже упоминалось, вращаясь вокруг собственной оси. Это имеет существенное значение, так как у эвглены, как я у некоторых других простейших, сильно и положительно реагирующих на свет, имеются хорошо развитые фоторецепторы. Это пигментные пятна, иногда снабженные даже отражающими образованиями, позволяющими животному локализовать световые лучи. Продвигаясь к источнику света описанным образом, эвглена поворачивает к нему то «слепую» (спинную) сторону, то «зрячую» (брюшную). И каждый раз, когда последняя (с незаслоненным участком «глазка») оказывается обращенной к источнику света, производится корректировка траектории движения путем поворота на определенный угол в сторону этого источника. Следовательно, движение эвглены к свету определяется положительным фотоклинотаксисом, причем в случае попадания ее под воздействие двух источников света попеременное раздражение фоторецептора то слева, то справа придает движению эвглены внешнее сходство с тропотаксисным поведением двусторонне-симметричных животных, обладающих парными глазами (рис. 28), о чем пойдет речь ниже.

«Глазки» описаны и у других жгутиковых. Например, массивный ярко-красный глазок имеет Collodictyon sparsevacuolata — своеобразный протист с 2–4 жгутиками и амебоидным обликом, способный быстро передвигаться как с помощью жгутиков, так и с помощью ложноножек. Особую сложность фоторецепция достигает у жгутикового Pauchetia (Dinoflagellata), у которого имеются уже аналоги существенных частей глаза многоклеточных животных, пигментное пятно снабжено не только светонепроницаемым экраном (аналог пигментной оболочки), но и све-топроницаемым образованием в форме сферической линзы (аналог хрусталика). Такой «глазок» позволяет не только локализовать световые лучи, но и собирать, в известной степени фокусировать их.

Пластичность поведения простейших

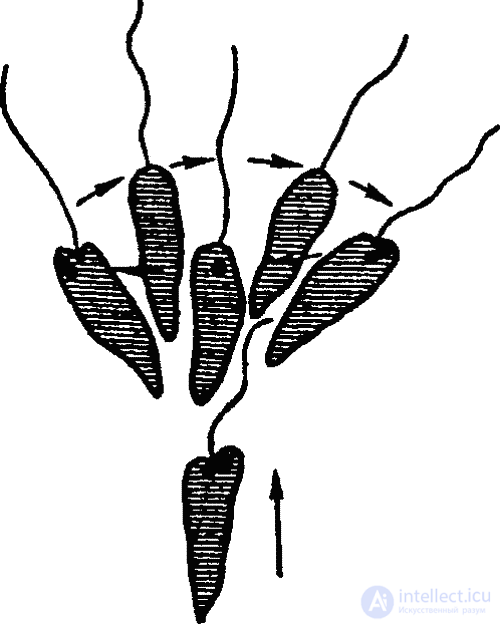

Как мы видим, и в моторной и в сенсорной сфере поведение достигает у ряда видов простейших известной сложности. Достаточно указать на фобическую реакцию (реакцию испуга) туфельки в вышеописанном примере клинотаксиса: наткнувшись на твердое препятствие (или попав в иную неблагоприятную зону), туфелька резко останавливается и принимает «оборонительное положение», т. е. «съеживается», готовясь пустить в ход ядовитые стрекательные капсулы. Одновременно меняются движения ресничек, происходит тактильное и химическое обследование объекта и т. д. У эвглены фобическая реакция выражается в том, что она, остановившись, начинает производить передним концом тела круговые движения, после чего уплывает в другом направлении (рис. 29).

Ясно, что такая интеграция моторно-сенсорной активности возможна лишь с помощью специальных функциональных структур, аналогичных нервной системе многоклеточных животных. Однако о морфологии этих аналогов еще очень мало известно, и только относительно инфузории удалось с определенной достоверностью доказать существование специальной сетевидной системы проводящих путей, располагающейся в эктоплазме. Очевидно, проведение импульсов осуществляется у простейших и системой градиентов в самой цитоплазме.

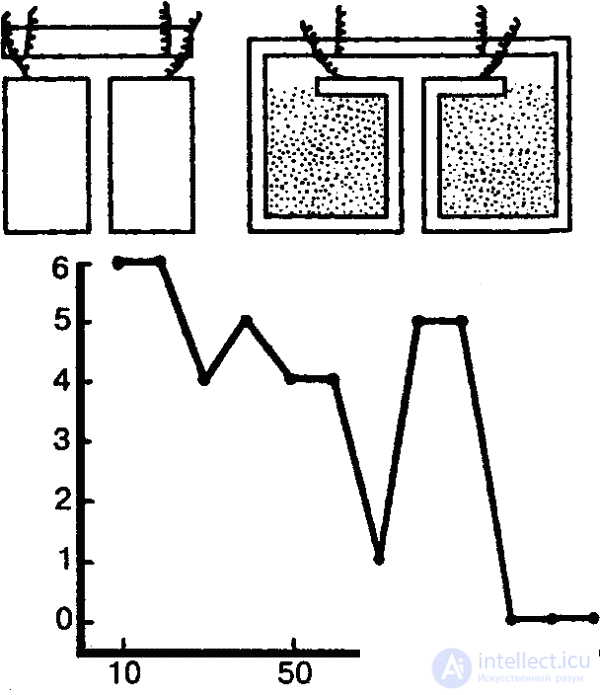

The ability to individually change the described genetically fixed forms of behavior through learning is weakly expressed in the simplest. Yet the ability of the simplest to learn, at least in elementary forms, can now be considered proven. If, for example, the paramecium is kept in a triangular or square (in cross section) vessel for some time, then they retain the usual path of movement along the vessel walls and after they move into a round vessel (Fig. 30). Similarly, an infusoria that had been floating for a long time (about two hours) in a vessel that had the shape of a triangle, followed this path in a square vessel of a larger area (experiments of the German scientist F. Bramstedt). In the experiments of the Soviet researcher N. A. T. Ushmalovaya infusoria were subjected to a permanent rhythmic stimulus - vibration. As a result, the animals gradually ceased to react to it in the usual way (contraction). The researcher sees in this an example of elementary trace reactions, which are a simple form of short-term memory, which is formed at this level of phylogenesis due to purely molecular interactions.

Similar experiments were made by other experimenters who used various forms of exposure. There were doubts whether it is really possible to talk about such forms of learning in such cases, since the strong effects could have at least a temporary adverse effect on the experimental animals. Moreover, in general in experiments with protozoa it is very difficult to take into account all possible side factors (especially chemical changes in the environment).

Yet, obviously, we are dealing here with an elementary form of learning - addiction. The addiction (to the changed external conditions), as we already know, plays an important role in the behavior of higher animals, but it has a qualitatively different character, if only because it is based not only on sensations, but also on perceptions. In the elementary sensory psyche, an animal can become accustomed only to the effects of individual stimuli (or their aggregates), which are the embodiment of individual properties or qualities of environmental components. This is exactly what took place in the examples given, when a modification of type-typical behavior was observed: innate reactions to certain stimuli are gradually eliminated, if a repeated biological repetition does not lead to a biologically significant effect. So, in experiments Tushmalova phobic reaction in ciliates with time was reduced to nothing when re-meeting with the "harmless" stimulus.

Habituation must be distinguished from fatigue, which is expressed in the phenomena of "exhaustion" of the animal. In Tushmalova’s experiments, this was expressed in the inability of the ciliates to react further if it was subjected to very strong irritations for 2–3 hours. Fatigue is associated with the overrun of energy resources, but habituation is an active adaptive response, the value of which is to save these resources, to prevent the waste of energy on movements that are useless for animals.

As a form of learning, addiction characterizes the lowest level of the elementary sensory psyche, although it does not lose its value at all levels of the development of the psyche, as was shown when familiarizing with the ontogeny of animal behavior (see part II). However, the highest representatives of the simplest ones may already have the rudiments of associative learning, which is generally characteristic of higher levels of mental development.

We can speak of associative learning in cases where a temporary connection is established between a biologically significant and a "neutral", more precisely, a biologically malovalent stimulus. It was this connection that Bramstedt managed to work out with a shoe, which, as already noted, does not react in a noticeable way to a change in lighting, but is very sensitive to temperature changes. If in the experiment we shade one half of a drop of water in which paramecias are floating and at the same time warm the illuminated part of the drop, then soon the ciliates will gather in the cold dark part, but remain there (for 15 minutes) after the temperature in both parts will be balanced. True, these experiments of Bramstedt were subjected to serious criticism, since during heating the chemistry of water also changes (the solubility of the gases contained in it changes), which cannot but influence the behavior of the infusoria (experiments of U. Grabowski).

At the same time, a similar result can be obtained by punishing animals when they swim into the illuminated area by strikes of electric current (Fig. 31). The avoidance effect was maintained in this case for 20 minutes (experiments of G. Zesta). However, the opposite result, that is, the avoidance of darkness and swimming in the illuminated zone, Zesta could not be obtained. This circumstance, however, is the result of a methodical error: galvanotaxis, expressed in their striving towards the cathode, is characteristic of ciliates. In the experiments of Zesta mentioned above, the cathode was always on the dark half and the galvanotoxis turned out to be stronger than electrical stimulation, which is why the ciliates were sent only to darkness.

In more thoroughly set experiments, the Polish scientist S. Vavrzhinchik managed to overcome these methodological shortcomings and successfully teach the ciliates to avoid the dark portion of the glass tube, where they were irritated by electric current. Gradually, the shoes more and more often remained in the illuminated zone and turned on the border with the darkened zone even when this boundary moved along the tube even before receiving an electric shock. Finally, they remained in the illuminated zone four times longer than in the dark, even when the electrical stimuli stopped altogether. This reaction persisted even for 50 minutes, which is a long enough period for the simplest. This researcher obtained clear positive results in other experiments.

True, J. Dembowski, who repeated these experiments with some changes, came to the conclusion that, although the possibility of working out the simplest conditioned reactions is not excluded, these experiments with shoes still do not completely solve the essence of the question, because there are incomparably stronger factors especially chemicals that mask reactions to light. Due to the absence of quite convincing experimental data, Dembovsky left the question of whether the simplest conditioned reactions were open.

At the same time, it was possible to develop contractile reactions in response to light stimulation after 140–160 combinations of other ciliates of infusoria, in particular, at the stenter and suwayka.

At ciliates were carried out and other experiments using different methodological techniques. In particular, capillaries were used, sometimes with a curved end, in which paramecia was planted, after which the time they needed for release was measured. In the newest studies carried out in this way, quite positive results were obtained: with each repetition of the experience, the release time of paramecium from the tube noticeably decreased, which is recognized as evidence of their ability to associative learning.

However, the American scientists F. B. Applied and F. T. Gardner, who recently repeated these experiments, consider such a conclusion to be unreasonable. These scientists consistently sucked in the same capillary different, never experienced shoes, and found that the time of release of these animals from the capillary also gradually decreases. But this did not happen if the capillary was thoroughly washed before use and boiled in deionized water. The use of the capillaries treated in this way to repeat the experiment with the same shoe did not give almost any learning effect. Hence, the experimenters deduced that the decrease in the exit time from the capillary is not a result of learning in paramecium, but a reaction to the contamination of the inner surface of the tube with metabolic products, which increases from experience to experience and from which the animals are trying to leave.

On the other hand, similar studies of other scientists took into account similar possible changes in the environment, and it was found that the time for the release of ciliates from the tube is reduced only in the first experiments, and then it remains constant (the medium in the tube must, however, continue to change).

Thus, the question of the presence of ciliates (and even more so among the simplest in general) of associative learning cannot yet be considered solved. Yet, obviously, such learning exists in their embryonic form.

General characteristics of mental activity

As we could see, at the lowest level of the elementary sensory psyche, the behavior of animals appears in quite diverse forms, but still we are dealing here only with primitive manifestations of mental activity. We can speak here of such activity, of the psyche, because the protozoa actively respond to changes in their environment, and they react to biologically not directly significant properties of environmental components as signals about the appearance of vital environmental conditions. In other words, the simplest is characterized by an elementary form of mental reflection — sensation, that is, sensitivity in the true sense of the word. But there, as we already know, where the capacity for sensation appears, the psyche begins.

It has already been said that even the lowest level of mental reflection is not the lowest level of reflection in general, existing in living nature: pre-psychic reflection is inherent in plants, in which only irritability processes take place. However, elements of such a dopsychic reflection are also found among the simplest.

Of great interest in this regard, as in general, is to understand the conditions for the emergence of mental reflection, the reaction of the simplest to temperature. Here, the energy directly needed to sustain life is still identical to the mediating energy, signaling the presence of a vital component of the environment.

As early as the beginning of our century, M. Mendelssohn found that in ciliates, reactions to changes in temperature become more differentiated as they approach a certain thermal optimum. So, at Paramecium aurelia, this optimum is within + 24 ... + 28 ° of water temperature. At + 6 ... + 15 ° the ciliate reacts to temperature differences from 0.06 to 0.08 °, at + 20 ... + 24 °, to the differences from 0.02 to 0.005 °. But according to modern data, this species tolerates low temperatures and even freezing to -30 ° or more.

However, the simplest specific thermoreceptors, i.e., special formations that serve to perceive changes in the temperature of the medium, were not found. (These receptors are not known reliably for other invertebrates.) At one time G. Jennings believed that in the infusoria (slippers) the front end of the body was especially sensitive in terms of temperature stimuli. However, later O. Köhler showed that in the case of a cut into two parts, the front and rear ends of the body behave in this respect, in principle, in the same way as the whole animal. This suggests the conclusion that the reaction to temperature changes in the simplest is a property of the whole protoplasm. It is possible that the reactions of protozoa to thermal stimuli are still similar to biochemical reactions of the type of enzymatic processes.

Obviously, all this corresponds to the fact that for the organism of the simplest, thermal energy is still not divided into the source of vital activity and the signal that such a source exists. In this regard, there are no special thermoreceptors. We have, therefore, here an example of “coexistence” with the simplest pre-mental and mental reflection.

Interestingly, the absence of thermoreceptors does not make the reactions of the simplest less expressive than their reactions to other external agents. As has been shown, these reactions manifest themselves in taxis (in this case, thermotaxis) and kinesis.

Even more clearly, the “coexistence” of the pre-psychic and mental reflection comes from the lower representatives of the type. In euglena, it is also due to the presence, along with the animal, of a vegetable, autotrophic type of food, why euglena applies equally to plants and animals.

On the other hand, we know that the qualities of mental reflection are determined by how developed the abilities to move, space-time orientation and to change innate behavior. In the simplest, we encounter various forms of movement in the aquatic environment, but only at the most primitive level of instinctive behavior — kinesis. The orientation of behavior is carried out only on the basis of sensations and is limited to elementary forms of taxis, allowing the animal to avoid adverse external conditions. With a few exceptions, the activity of protozoa is in general, as it were, under a negative sign, because these animals fall within the scope of action of positive stimuli, avoiding negative ones.

This means that the search phase of instinctive behavior (kinesis) in this respect is still extremely underdeveloped. Moreover, it is clearly devoid of a complex, multi-stage structure. It is possible that in many cases this phase is completely absent. In all this, not only is the exceptional primitiveness of instinctive behavior at this level manifested, but also the extreme paucity of the content of mental reflection. After all, this content is filled primarily with active search and evaluation of stimuli in the early stages of the search phase.

As already noted, in some cases, the simplest ones also have positive elements of spatial orientation. To the already mentioned examples of positive taxis, one can add that the amoeba is able to find a food object at a distance of up to 20-30 microns. The beginnings of an active search for prey exist, obviously, in predatory ciliates. However, in all these cases, positive taxis reactions still do not have the character of a genuine search behavior, so these exceptions do not change the overall assessment of the simplest behavior, and even more so the characteristic of the lowest level of the elementary sensory psyche as a whole: distantly components of the environment are recognized at this level; biologically “neutral” signs of positive components, as a rule, are not yet perceived as signaling from a distance, i.e., they simply do not exist for the animal as such. Thus, mental reflection performs mainly a watchdog function at the lowest level of its development and therefore differs by its characteristic “one-sidedness”: the accompanying biologically insignificant properties of environmental components are distantly perceived by animals as signals of the appearance of such components only if these components are for animals. harmful.

As for, finally, the plasticity of the behavior of the simplest, even here the simplest have only the most elementary possibilities. This is quite natural: only elementary learning can correspond to an elementary instinctive behavior. The latter, as we have seen, is represented by the most primitive form - addiction, and only in some cases, perhaps, are the rudiments of associative learning.

Of course, with all its primitiveness, the simplest behavior is still quite complex and flexible, at least to the extent that is necessary for life in the peculiar conditions of the microworld. These conditions differ in a number of specific features, and this world cannot be imagined as simply a reduced macrocosm many times. In particular, the medium of the microworld is less stable than the medium of the macroworld, which is manifested, for example, in the periodic drying of small water bodies. On the other hand, the short duration of life of microorganisms as separate individuals (frequent change of generations) and the relative monotony of this microworld make the development of more complex forms of accumulation of individual experience unnecessary. In this microenvironment there are no such complex and diverse conditions to which you can adapt only by learning. In such conditions, the plasticity of the simplest structure itself, the ease of formation of new morphological structures sufficiently ensure the adaptability of these animals to the conditions of existence. It can obviously be said that the plasticity of behavior here has not yet surpassed the plasticity of the structure of the organism.

As already noted, protozoa are not a homogeneous group of animals, and the differences between their different forms are very large. Higher representatives of this type in many respects developed in peculiar forms of non-cellular structure parallel to the lower multicellular invertebrate animals. As a result, highly developed protozoans sometimes display even more complex behavior than some multicellular invertebrates, which are also at the lowest level of the elementary sensory psyche. Это тоже одна из причин, почему мы описали этот уровень психического развития на примере только простейших. Здесь наглядно выступает уже отмеченная общая закономерность: психологическая классификация не вполне совпадает с зоологической, так как некоторые представители одной и той же таксономической категории могут еще находиться на более низком психическом уровне, другие — уже на более высоком. Именно последнее имеет место у высших представителей типа простейших, которых в этом отношении можно было бы рассматривать как исключения. Однако, в сущности, это не так, ибо здесь проявляется и другая закономерность эволюции психики, а именно: элементы более высокого уровня психического развития всегда зарождаются в недрах предшествующего, более низкого уровня. В данном случае, например, примитивные формы ассоциативного научения, вообще характерные для более высокого уровня элементарной сенсорной психики, встречаются в зачатке уже у некоторых видов, относящихся к типу, который в целом стоит на низшем уровне элементарной сенсорной психики, где типичной формой индивидуально-изменчивого поведения является привыкание.

Высший уровень развития элементарной сенсорной психики

Высшего уровня элементарной сенсорной психики достигло большое число многоклеточных беспозвоночных. Однако, как отмечалось, часть низших многоклеточных беспозвоночных находится в основном на том же уровне психического развития, что и многие простейшие. Это относится прежде всего к большинству кишечнополостных и к низшим червям, а тем более к губкам, которые во многом еще напоминают колониальные формы одноклеточных (жгутиковых). Неподвижный, сидячий образ жизни взрослых губок привел даже к редукции их внешней активности, поведения (при полном отсутствии нервной системы и органов чувств). Но даже у самых примитивных представителей многоклеточных животных создались принципиально новые условия поведения в результате появления качественно новых структурных категорий — тканей, органов, систем органов. Это и обусловило возникновение специальной системы координации деятельности этих многоклеточных образований и усложнившегося взаимодействия организма со средой — нервной системы.

К низшим многоклеточным беспозвоночным относятся помимо уже упомянутых еще иглокожие, высшие (кольчатые) черви, отчасти моллюски и др.

Мы рассмотрим в дальнейшем в качестве примера кольчатых червей, у которых в полной мере выражены признаки поведения, характерные для высшего уровня элементарной сенсорной психики. К кольчатым червям относятся живущие в морях многощетинковые черви (полихеты), малощетинковые черви (наиболее известный представитель — дождевой червь) и пиявки. Характерным признаком строения кольчецов является внешняя и внутренняя метамерия: тело состоит из нескольких большей частью идентичных сегментов, каждый из которых содержит «комплект» внутренних органов, в частности пару симметрично расположенных ганглиев с нервными коммисурами. В результате нервная система кольчатых червей имеет вид «нервной лестницы».

Nervous system

Как известно, нервная система впервые появляется у низших многоклеточных беспозвоночных. Возникновение нервной системы — важнейшая веха в эволюции животного мира, и в этом отношении даже примитивные многоклеточные беспозвоночные качественно отличаются от простейших. Важным моментом здесь является уже резкое ускорение проводимости возбуждения в нервной ткани: упротоплазме скорость проведения возбуждения не превышает 1–2 микрон в секунду, но даже в наиболее примитивной нервной системе, состоящей из нервных клеток, она составляет 0,5 метра в секунду!

Нервная система существует у низших многоклеточных в весьма разнообразных формах: сетчатой (например, у гидры), кольцевой (медузы), радиальной (морские звезды) и билатеральной. Билатеральная форма представлена у низших (бескишечных) плоских червей и примитивных моллюсков (хитон) еще только сетью, располагающейся вблизи поверхности тела, но выделяются более мощным развитием несколько продольных тяжей. По мере своего прогрессивного развития нервная система погружается под мышечную ткань, продольные тяжи становятся более выраженными, особенно на брюшной стороне тела. Одновременно все большее значение приобретает передний конец тела, появляется голова (процесс цефализации), а вместе с ней и головной мозг — скопление и уплотнение нервных элементов в переднем конце. Наконец, у высших червей центральная нервная система уже вполне приобретает типичное строение «нервной лестницы», при котором головной мозг располагается над пищеварительным трактом и соединен двумя симметричными коммисурами («окологлоточное кольцо») с расположенными на брюшной стороне подглоточными ганглиями и далее с парными брюшными нервными стволами. Существенными элементами являются здесь ганглии, поэтому говорят и о ганглионарной нервной системе, или о «ганглионарной лестнице». У некоторых представителей данной группы животных (например, пиявок) нервные стволы сближаются настолько, что получается «нервная цепочка».

От ганглиев отходят мощные проводящие волокна, которые и составляют нервные стволы. В гигантских волокнах нервные импульсы проводятся значительно быстрее благодаря их большому диаметру и малому числу синаптических связей (мест соприкосновения аксонов одних нервных клеток с дендритами и клеточными телами других клеток). Что же касается головных ганглиев, т. е. мозга, то они больше развиты у более подвижных животных, обладающих и наиболее развитыми рецепторными системами.

Зарождение и эволюция нервной системы обусловлены необходимостью координации разнокачественных функциональных единиц многоклеточного организма, согласования процессов, происходящих в разных частях его при взаимодействии с внешней средой, обеспечения деятельности сложно устроенного организма как единой целостной системы. Только координирующий и организующий центр, каким является центральная нервная система, может обеспечить гибкость и изменчивость реакции организма в условиях многоклеточной организации.

Огромное значение имел в этом отношении и процесс цефализапии, т. е. обособления головного конца организма и сопряженного с ним появления головного мозга. Только при наличии головного мозга возможно подлинно централизованное «кодирование» поступающих с периферии сигналов и формирование целостных «программ» врожденного поведения, не говоря уже о высокой степени координации всей внешней активности животного.

Разумеется, уровень психического развития зависит не только от строения нервной системы. Так, например, близкие к кольчатым червям коловратки также обладают, как и те, билатеральной нервной системой и мозгом, а также специализированными сенсорными и моторными нервами. Однако, мало отличаясь от инфузории размером, внешним видом и образом жизни, коловратки очень напоминают последних также поведением и не обнаруживают более высоких психических способностей, чем инфузории. Это опять показывает, что ведущим для развития психической деятельности является не общее строение, а конкретные условия жизнедеятельности животного, характер его взаимоотношений и взаимодействий с окружающей средой. Одновременно этот пример еще раз демонстрирует, с какой осторожностью надо подходить к оценке «высших» и «низших» признаков при сравнении организмов, занимающих различное филогенетическое положение, в частности при сопоставлении простейших и многоклеточных беспозвоночных.

Movements

Кольчатые черви обитают в морях и пресноводных водоемах, но некоторые ведут и наземный образ жизни, передвигаясь ползком по субстрату или роясь в рыхлом грунте. Морские черви отчасти пассивно носятся течениями воды как составная часть планктона, но основная масса ведет придонный образ жизни в прибрежных зонах, где селится среди колоний других морских организмов или в расщелинах скал. Многие виды живут временно или постоянно в трубках, которые в первом случае периодически покидаются их обитателями, а затем вновь разыскиваются. Хищные виды отправляются из этих убежищ регулярно на «охоту». Трубки строятся из песчинок и других мелких частиц, которые скрепляются выделениями особых желез, чем достигается большая прочность построек. Неподвижно сидящие в трубках животные ловят свою добычу (мелкие организмы), подгоняя к себе и процеживая воду с помощью венчика щупалец, который высовывается из трубки, или же прогоняя сквозь нее поток воды (в этом случае трубка открыта на обоих концах).

В противоположность сидячим формам свободноживущие черви активно разыскивают свою пищу, передвигаясь по морскому дну: хищные виды нападают на других червей, моллюсков, ракообразных и иных сравнительно крупных животных, которых хватают челюстями и проглатывают; растительноядные отрывают челюстями куски водорослей; другие черви (их большинство) ползают и роются в придонном иле, проглатывают его вместе с органическими остатками или собирают с поверхности дна мелкие живые и мертвые организмы.

Малощетинковые черви ползают и роются в мягком грунте или придонном иле, некоторые виды способны плавать. Во влажных тропических лесах некоторые малощетинковые кольчецы вползают даже на деревья. Основная масса малощетинковых червей питается детритом, всасывая слизистый ил или прогрызаясь сквозь почву. Но существуют и виды, поедающие мелкие организмы с поверхности грунта, процеживающие воду или отгрызающие куски растений. Несколько видов ведут хищный образ жизни и захватывают мелких водных животных, резко открывая ротовое отверстие. В результате добыча всасывается с потоком воды.

Пиявки хорошо плавают, производя туловищем волнообразные движения, ползают, роют ходы в мягком грунте, некоторые передвигаются по суше. Помимо кровососущих существуют также пиявки, которые нападают на водных беспозвоночных и проглатывают их целиком. Наземные пиявки подстерегают свои жертвы на суше (млекопитающих и людей), в траве или на ветках деревьев и кустарников (во влажных тропических лесах). Эти пиявки могут довольно быстро двигаться. В передвижении наземных пиявок по субстрату большую роль играют присоски: животное вытягивает сперва туловище, затем присасывается к субстрату головной присоской, притягивает к ней задний конец туловища (с одновременным сокращением последнего), присасывается задней присоской и т. д.

Итак, двигательная активность кольчатых червей как при локомоции, так и при добывании пищи отличается большим многообразием и достаточной сложностью. Обеспечивается это сильно развитой мускулатурой, представленной прежде всего так называемым кожно-мышечным мешком. Он состоит из двух слоев: внешнего (подкожного), состоящего из кольцевых волокон, и внутреннего, состоящего из мощных продольных мышц. Последние простираются, несмотря на сегментацию, от переднего до заднего конца туловища. Ритмичные сокращения продольной и кольцевой мускулатуры кожно-мышечного мешка обеспечивают локомоцию: червь ползет, вытягивая и сокращая, расширяя и сужая отдельные части своего тела. Так, у дождевого червя вытягивается (и сужается) передняя часть тела, затем то же самое происходит последовательно со следующими сегментами. В результате по телу червя пробегают «волны» сокращений и расслаблений мускулатуры.

У кольчатых червей впервые в эволюции животного мира появляются подлинные парные конечности: кольчецы (помимо пиявок) носят на каждом сегменте по паре выростов, служащих органами передвижения (кроме головного конца, где они служат ротовыми органами) и получивших название параподий. Параподии снабжены специальными мышцами, двигающими их вперед или назад. Зачастую параподий имеют ветвистое строение. Каждая ветвь снабжена опорной щетинкой и, кроме того, венчиком из щетинок, имеющих у разных видов различную форму. От параподий отходят и щупальцевидные органы тактильной и химической чувствительности. Особенно длинными и многочисленными последние являются на головном конце, где на спинной стороне располагаются глаза (одна или две пары), а в ротовой полости или на особом (выпячиваемом) хоботке — челюсти. В захвате пищевых объектов могут участвовать и нитевидные щупальца на головном конце червя.

У ряда многошетинковых и всех малощетинковых червей параподии редуцированы (отсюда и название последних), остались лишь посегментно расположенные пучки щетинок. Так, у дождевого червя на каждом сегменте находится по четыре пары очень коротких, неразличимых невооруженным глазом щетинок, которые, однако, наподобие параподии служат для передвижения животного: являясь достаточно крепкими подвижными рычагами, они обеспечивают вместе с сокращениями кожно-мышечного мешка поступательное движение червя. С другой стороны, растопыривая свои щетинки и упираясь ими в грунт, дождевой червь настолько прочно фиксирует свое тело в земле, что практически невозможно вытащить его оттуда в неповрежденном виде. У некоторых других малощетинковых червей щетинки развиты значительно сильнее и представлены в большем количестве.

Органы чувств и сенсорные способности

Большой интерес для познания психической деятельности низших многоклеточных беспозвоночных представляет устройство и функционирование их органов чувств, представленных также весьма различными образованиями в соответствии с общим уровнем организации животного.

У наиболее низкоорганизованных представителей беспозвоночных органы чувств еще очень слабо дифференцированы как в морфологическом, так и в функциональном отношении. У этих животных трудно выделить органы осязания, химической чувствительности и т. д. Очевидно, первичные органы чувств вообще были плюромодальными, т. е. они обладали лишь общей, присущей всей живой материи чувствительностью, но в повышенной степени. Существование таких плюромодальных чувствительных клеток является весьма вероятной гипотезой, но в настоящее время такие рецепторные клетки, очевидно, уже не существуют. Специализация таких клеток по отдельным видам энергии привела к появлению унимодальных рецепторных образований, которые, как правило, реагируют лишь на один специфический вид энергии. Так появились термо-, хемо-, механо-, фото- и другие рецепторы.

Согласно этой гипотезе, все органы чувств многоклеточных животных развились из органов осязания — наименее дифференцированных рецепторов. В наиболее элементарных случаях осязательная функция присуща всем клеткам поверхности тела. Но уже у кишечнополостных появляются специальные осязательные клетки, которые, скапливаясь в определенных местах, образуют подлинные органы осязания. Это вытянутые цилиндрические или веретеновидные клетки, несущие на конце неподвижный чувствительный волосок или пучок волосков. Однако эти органы часто выполняют и обонятельную функцию. Особенностью низших многоклеточных беспозвоночных является то, что во многих (хотя и не во всех) случаях эти две рецепторные функции слиты и не поддаются морфологическому разграничению.

В этом нетрудно усмотреть остатки первичной плюромодальности.

С другой стороны, органы зрения относятся к наиболее сложным по строению и функционированию. Иногда органы чувств низшего порядка превращаются в органы чувств высшего порядка (например, у пиявок некоторые из органов осязания — так называемые «сенсиллы» — превращаются в глаза). Известный советский зоолог, специалист по сравнительной анатомии беспозвоночных B-А. Догель говорил в таких случаях о «повышении органа в ранге». Однако в процессе филогенеза, как отмечает Догель, нередко имело место и обратное явление; в других случаях какие-то рецепторы беспозвоночных исчезали, чтобы потом вновь появиться в несколько измененной форме. Это непостоянство и легкость перестройки привели к тому, что у близкородственных беспозвоночных однотипные рецепторы, в частности органы оптической чувствительности, подчас бывают совершенно различными по строению и функциям.

Если взять, к примеру, кишечнополостных, то гидра четко реагирует на свет, хотя специальных органов зрения у нее нет. Она воспринимает свет всей поверхностью тела. Положительный фототаксис гидры выражается в том, что животное производит в освещенной сфере круговые или маятникообразные колебательные движения и в конце концов занимает положение в сторону источника света или даже направляется (ползет) к нему. Свободноживущие же представители кишечнополостных — медузы — обладают уже специальными многоклеточными органами светочувствительности. В простейшем случае эти органы представлены так называемыми глазными пятнами, которые находятся среди обыкновенных эпителиальных клеток, и даже нечетко отграничены от них. Более дифференцированным рецептором является глазная ямка (рис. 32). Однако чаще у медуз встречаются уже настоящие глаза, причем наиболее сложно устроенные из них представляют собой погруженные под слоем эпителиальных клеток глазные пузыри приблизительно шарообразной формы. Эпителий над глазным пузырем утончен и представляет собой прозрачную роговицу. Дно и стенки пузыря состоят из двух типов клеток: ретинальных и пигментных, причем ретинальные клетки снабжены чувствительными палочками. В полости глазного пузыря находится стекловидное тело — студенистая масса, защищающая ретину от механических повреждений. Иногда встречаются даже хрусталик и радужка, и тогда налицо все основные компоненты глаза высших животных (нет, однако, глазодвигательных мышц и систем фокусировки).

Учитывая, что глазное пятно является исходной формой вообще всех органов зрения, можно, следовательно, в ряду медуз проследить путь усложнения структуры от самого примитивного органа светочувствительности до сложного, высокодифференцированного глаза.

Очень разнообразны по своему строению и глаза червей, как и других низших многоклеточных беспозвоночных; в принципе к ним относится то же, что говорилось в отношении глаз медуз. В соответствии с многообразием движений кольчатых червей, разнообразием способов добывания пищи и других моментов жизнедеятельности находится и уровень развития сенсорной сферы этих животных. Это, правда, не означает, что у кольчецов имеются рецепторы для всех видов энергии, воздействующих на них, или даже что для всех форм чувствительности имеются специальные органы чувств. Так, например, у кольчатых червей встречаются сложно устроенные глаза, снабженные даже хрусталиками. Имеются весьма сложные глаза и у некоторых планарий и улиток. По их обладатели, насколько известно, неспособны к зрительному восприятию предметов. За исключением, может быть, некоторых улиток, у всех этих животных фотоскопические глаза, позволяющие отличать свет от тьмы и направление, откуда световые лучи падают на животное, а также перемещение светотеней в непосредственной близости от животного. Светочувствительность может при этом быть очень высокой, например, гребешок, двустворчатый моллюск с несколькими десятками глаз, закрывает створки раковины уже при уменьшении интенсивности освещения на 0,3 %. (Для сравнения можно указать, что человек воспринимает уменьшение освещения лишь не менее чем на 1 %).

Большой интерес представляют активно плавающие многощетинковые кольчатые черви из семейства Alciopidae, ведущие хищный образ жизни. У этих полихет глаз не только отличается исключительно сложным строением и величиной, но и снабжен аккомодационным устройством в виде специальных сократительных волокон, способных передвигать хрусталик и тем самым менять фокусное расстояние. Это единственный известный случай среди низших беспозвоночных: аккомодация глаза встречается только у головоногих моллюсков и позвоночных. Возможно, у этих червей в какой-то степени уже существует предметное зрение, что было бы исключением, подтверждающим общее правило. Это относится и к свободно плавающим хищным моллюскам Heteropoda, которые тоже обладают весьма сложно устроенными глазами с приспособлением, заменяющим аккомодацию.

Что же касается дождевого червя, то здесь обнаруживается чрезвычайно интересный факт: у него нет не только сложно устроенных, но и вообще никаких специальных органов светочувствительности. Вместе с тем ему свойствен четкий отрицательный фототаксис. Функцию светоощущения выполняют рассеянные в коже светочувствительные клетки. Это пример кожной светочувствительности низших многоклеточных беспозвоночных. Кожная светочувствительность наблюдается и у многих моллюсков, причем у двустворчатых это нередко единственная форма фоторецепции. Эти моллюски реагируют как на освещение, так и на затемнение чаще всего одинаковым образом — втягиванием выступающих из раковин частей тела или запиранием раковины. Многие улитки реагируют на внезапное затемнение сокращением «ноги», причем эта реакция сохраняется и после экстирпации глаз, что опять-таки указывает на наличие кожной светочувствительности.

The response of the earthworm to the lighting conditions is that it crawls into a zone of greater darkening. If, however, the intensity of the illumination is suddenly reduced, the worm responds to this with movements of flight; under natural conditions, it creeps into the soil. The same reaction follows the sudden lighting. If, however, only a certain part of the earthworm's body is illuminated, the time of this reaction is reduced in proportion to the size of the illuminated surface area of the body — the worm reacts the most when it illuminates its entire surface. Consequently, the reaction is determined by the gradient of stimulation of the illuminated and unlit parts of the body. Similarly, they react to light and other ringed worms.

Ringed worms also react to contact, chemical and thermal irritation, gravity, electrical irritation, water flow, and terrestrial forms (earthworms) - to the humidity of the environment. However, there are no fundamental differences from the reaction to light: all these reactions are at the same level and are characterized by the fact that they are responses to individual stimuli, to individual signs, the qualities of objects, but not to the objects themselves. Thus, for example, multi-and small-necked worms exhibit distinct taxis reactions to tactile stimuli. Negative reactions predominate, but in some cases positive tigmotaxis are also observed: touching the nerve segments of an animal to a substrate entails pressing down to it with the whole body, which is, of course, of great importance when digging for life or living in tubes. Interestingly, in the earthworm, the corresponding receptor formations are represented only by individual sensitive cells scattered throughout the body, but more densely located at its front end. In polychaete worms, tactile organs are often tentacles or setae.

Chemical sensitivity is also well developed, and in most cases negative chemotaxis is observed. With a high intensity of chemical exposure, worms always react negatively. On the other hand, an earthworm, for example, is capable of selecting different types of leaves for chemical reasons, indicating specialization in the sensory field. The organs of chemical sensitivity in the form of pits located near the mouth opening have been found in a number of kolchets. This especially applies to floating species that have a pair of such pits lined with ciliated epithelium.

Taxis

As at the lower levels of evolutionary development, spatial orientation occurs at the highest level of the elementary sensory psyche, mainly based on primitive taxis. But with the increasing complexity of the vital activity of organisms, the requirements for the localization of biologically significant components of the environment according to their biologically insignificant characteristics increase. There is a need for more complex taxis behavior, allowing the animal to feel and react quite clearly and differentially. This is precisely what distinguishes animals that are at the level of development of the psyche considered here: thanks to the symmetrical arrangement of the sense organs, along with kinesses and elementary taxis, they also find some higher forms of taxis behavior.

The German scientist A. Kuhn identified the following categories of higher taxis, which, however, are fully developed only in higher animals: tropotaxis - movement is oriented along the resultant, formed as a result of leveling the intensity of excitation in symmetrically located receptors; telotaxis - selection and fixation of one source of irritation and direction of movement to this source (“target”); menotaxis - in case of asymmetrical stimulation in symmetrically located receptors, the movement is made at an angle to the source of irritation. The menotaxis play a leading role in keeping animals in a constant position in space.

In addition, in higher animals with developed memory, there is another form of taxis - mnemotaxis, in which the main role is played by individual memorization of landmarks, which is especially important for territorial behavior, which will be discussed later.

In the behavior of koltstsov, tropic and telotaxis most often appear together: if an animal is subjected to simultaneous influence of two energy sources (for example, light) of the same force, then with a positive taxis it will initially move in the direction of the resultant, i.e., the line leading to the middle distance between sources (tropotaxis), but then, as a rule, before reaching this point, it will turn and go to one of the energy sources (telotaxis).

Most clearly, tropotaxis and telotaxis are manifested in actively moving ringed worms, primarily in predators. The latter not only detect the presence of the victim according to the physical and chemical stimuli emanating from it, but also are directed towards it, being guided on the basis of such taxis. Terrestrial leeches, for example, are able to precisely localize the location of the prey, and with surprising speed move toward it, focusing on the shaking of the substrate, and then, at a closer distance, and on the heat and smell coming from the prey (large mammals). As a result, the predator detects it by the corresponding gradients using a combination of positive vibrational, thermal, and chemical telotaxis.

In menotaxis, the animal, as was said, moves at an angle to the line of action coming from the source of energy. A typical example is the orientation of migrating animals along a solar (or other astronomical) “compass,” which, of course, is especially characteristic of migratory birds. In lower multicellular invertebrates, menotaxis is found in some snails. If these animals are placed on a side illuminated and slowly rotating disk, they, moving against the direction of rotation, adhere to a certain angle relative to the light source. In these cases, therefore, we can already speak of the orientation of the animal along the light compass, which plays an exceptional role in the life of higher animals.

The rudiments of higher forms of behavior

Polychaeteworms belong to the most psychologically advanced lower invertebrates. Their behavior is sometimes very complex and of particular interest in the sense that it contains a number of elements of mental activity inherent in more highly organized animals. In contrast to the majority of lower invertebrates, polychaetes exhibit some significant complications of type-typical behavior, partly already beyond the limits of the typical elementary sensory psyche.

So, in some cases, these sea worms have actions that can already be called constructive, since animals actively create structures from separate foreign particles, fastening them into a single whole. We are talking about the construction of the already mentioned "houses" - tubes of individual particles that are collected by worms on the seabed and strengthened with the help of special "working" organs - transformed front parapodias.

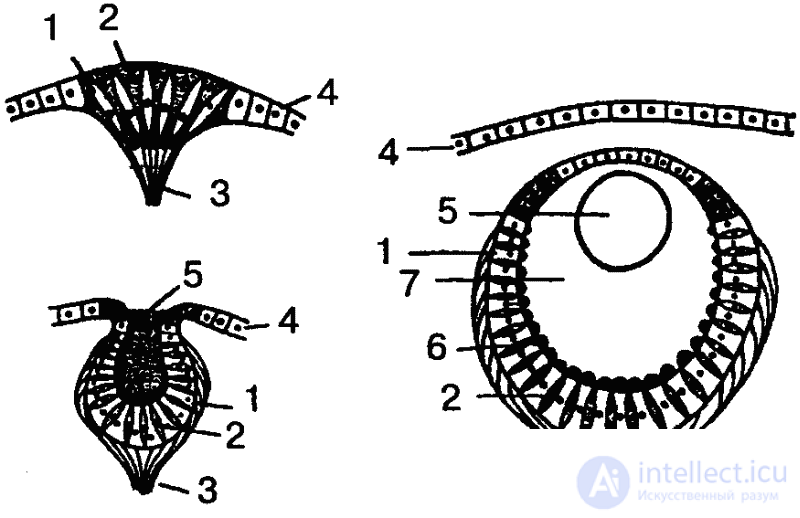

The pipe construction process itself is a complex activity consisting of several phases that adequately change depending on external factors such as the nature of the soil and current, the bottom relief, the number and composition of particles sinking to the bottom, the speed of their sedimentation, etc. various kinds of small detritus (for example, pieces of shells), grains of sand, particles of plants, etc., which are held together by special secretions of a special “cementing organ”. Particles suitable for consumption are selected by animals, and depending on their age; young individuals use only small granules, older - larger ones. All particles are collected and attached to each other by the already mentioned specialized tentacles. Polychaete Aulophorus carteri, for example, builds pipes from spores of aquatic plants, which it collects and attaches to each other around itself, just as a pipe is made of bricks (Fig. 33).

Of no less interest are the manifestations of mating behavior and aggressiveness that are first observed in polychaeta worms, and with them the elements of communication. Of course, genuine aggressiveness and mating behavior are characterized by ritualization, which appears only in cephalopod mollusks and arthropods, that is, at the lowest level of perceptual psyche. Nevertheless, representatives of the genus Nereis managed to observe the struggle between the two worms. In Nereis pelagica, such a struggle can begin (but not necessarily) if one individual tries to penetrate the “house” of another individual. Sometimes an invading individual bites the owner of the “house” at the rear end of the body, and then the “owner” leaves the phone or, having turned over, enters the fight with the alien. In other cases, when animals meet in a tube halfway, head to head, the fight breaks out immediately, and the worms fight, with their abdominal sides and heads towards each other. However, in all circumstances, animals do not damage each other. In a more fierce, "irreconcilable" form, the struggle takes place in the Nereis caudata, and not only because of the possession of the "house". The “fights” are described by the English researcher of the behavior of sea-ringed worms S. M. Evans and his collaborators also in the polychaete Harmothoe imbricata. In this species, the struggle may occur if two individuals are accidentally meeting, especially aggressiveness is manifested in the field of reproduction, when pairs are formed: the male clinging to the female becomes extremely aggressive towards other males (but not females). Never, however, the struggle is not accompanied by the supply of any signals or other manifestations of ritualization of behavior.

Grape snails, on the other hand, perform complex “marriage games,” sometimes lasting several hours, during which partners take different poses to each other, prick each other with lime lime spicules (“love arrows”), etc. Only after such mutual stimulation mating itself begins (spermatophoric transfer). In some years, for example, in Platynereis dumerilii, mating "dances" have also been described in recent years, but it is obviously too early to draw conclusions about their specific meaning and whether they have anything to do with ritualized behavior. But in all these cases, undoubtedly, some rudiments are found, anticipating much more complex behaviors of higher vertebrates.

Plasticity of behavior

The behavior of annelids, like other lower invertebrates, is characterized by low plasticity and conservatism. Inborn stereotypes prevail (“innate behavior programs”). Individual experience, learning, still plays a small role in the life of these animals. Associative relations are formed with them with difficulty and only to a limited extent. The results of learning are not stored for long. All ringed worms have the simplest form of learning — addiction, which we have already met with the simplest, in which it is the main, if not the only, form of modification of innate, type-specific behavior. In the lower multicellular animals, innate reactions to certain stimuli also cease after repeated repetitions, unless adequate reactions of these reactions are followed. So, for example, earthworms stop responding to re-shading if it remains without consequences.

There is an addiction in the field of eating behavior: if a polychaemal worm is re-“fed” with lumps of paper dipped in the juice of its usual victim, it stops taking them. If, alternately with such lumps, to give him authentic pieces of food, then he eventually learns to distinguish them and will reject only inedible paper. Similar experiments were made on the intestinal cavities (on polyps, which are, as we already know, at a lower level of the elementary sensory psyche). At the same time, polyps behaved in the same way as sea worms: after several (up to 5) experiments, they discarded inedible objects even before they were brought to the mouth opening. Interestingly, the untrained tentacles did not do this, even being close to the trained ones.

These experiments are interesting because they show the ability of lower invertebrates to distinguish edible from inedible by side physical qualities (the taste of the proposed objects were the same), which confirms the existence of true mental reflection already at this lower level of phylogenetic development. After all, a mediated action is performed here, characterized in that a property (or a combination of several properties) that the animal is guided by in evaluating the suitability of an object for food consumption acts as a true signal, and the sensitivity of a worm or polyp plays the role of an intermediary between the organism and the environment component, from which the existence of an animal depends directly.

More complex learning through “trial and error” and the formation of a new individual motor response can be detected in elementary form, starting with flatworms. So, planarians, meeting a strip of sandpaper on their way, first stop, but then still crawl through it. If you combine the contact of the worm with sandpaper with its concussion, then the planarians stop crawling through it even when no concussion is made. True, here, obviously, there is still no true association between the two stimuli (roughness and concussion); most likely, the summation of the initially not very strong negative irritation (roughness) occurs with additional negative irritation (concussion) and that probably entails a general increase in the excitability of the animal.

Nevertheless, it is already possible to work out even more complex reactions with the planarian when one of the stimuli is biologically "neutral." In such cases, one can speak, obviously, already of the elementary processes of genuine associative learning. So, for example, L. G. Voronin and N. A. Tushmalova were able to work out defensive and food conditioned reflexes from the planarian and ringed worms. At the same time, data were obtained indicating that the forms of temporary connections are becoming more complex. If it is possible to speak only of primitive unstable conditioned reflexes about flatworms, then already stable self-restoring conditioned reflexes are found in polychaeta worms. These differences correspond to deep morphological differences in the structure of the nervous system of these groups of animals and indicate a significant progress of mental activity in polychaeta.

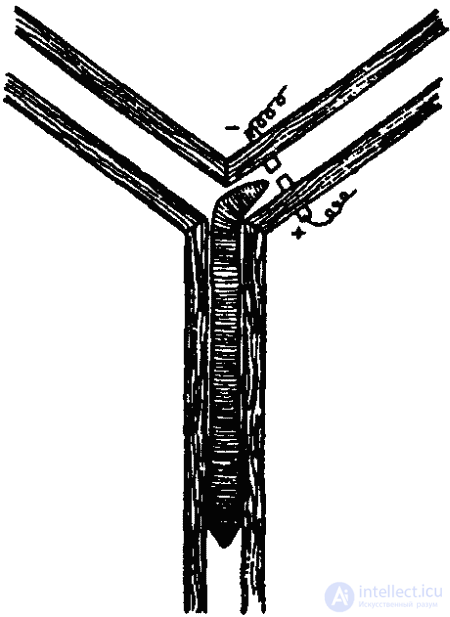

The plasticity of the behavior of earthworms was very convincingly shown back in 1912 by the famous American zoopsychologist R. Yerks. In his experiments, the worms had to choose a certain side in the T-shaped labyrinth, where the "nest" was located (in the opposite side, the worm received an electric shock). To teach the worms this, it took 120–180 experiments. (Snails master this task after 60 experiments and memorize the correct solution for 30 days.) Subsequently, similar experiments with earthworms were made by L. Heck, I. S. Robinson, RI Voyutsyak (Fig. 34) and other researchers. It was also possible to retrain the worms, changing the "socket" and electrodes in some places. It is characteristic that the result of learning does not change even after the removal of the front segments. Moreover, even deprived from the very beginning of these segments, the worm is able to learn how to correctly navigate the maze.

At one time, similar facts prompted V. A. Wagner to talk about the "segmental psychology" of annelids and other "articulate", bearing in mind that the ganglia of each segment to a large extent provide for the autonomous fulfillment of elementary mental functions. Headless kolchetsy, Wagner wrote, "do not lose the ability to spontaneous movements, except for those who are directly related and connected with the senses of the head ... Headless worms retain their instinctive actions, even those in which the head is directly involved." [52]