Lecture

Since ancient times, man has tried to somehow realize his attitude to the animal world, looking for signs of similarities and differences in the behavior of the latter. This is evidenced by the exceptional role that animal behavior plays in countless ancient tales, legends, beliefs, religious rites, etc.

With the birth of scientific thinking, the problem of the “soul” of an animal, its psyche and behavior became an important part of all philosophical concepts. As already noted when discussing the problem of instinct and learning, some ancient thinkers held opinions about close relationship and equally high level of human and animal mental life, while others, on the contrary, defended the superiority of the human psyche, while others categorically denied any connection with the mental activity of animals. As in other areas of knowledge, the theoretical constructions of ancient scientists, only partially based on direct observations, then determined over a millennium and more views on the behavior of animals, except for unscientific clerical-dogmatic interpretations of the Middle Ages.

The forerunners of the creators of evolutionary doctrine abandoned arbitrary interpretations of the similarities and differences in the psyche of animals and humans and turned to the facts that the nascent scientific natural history was extracting. So, already J.-O. Lametri drew attention to the similarity of the structure of the brain of man and mammals. At the same time, he noted that a person has significantly more brain convolutions.

In the struggle for evolutionary doctrine, seeking to substantiate the position of the continuity of development of the entire organic world as a whole, Charles Darwin and his followers unilaterally emphasized the similarity and kinship of all mental phenomena ranging from lower organisms to humans. This applies especially to Darwin’s denial of the qualitative differences between the human psyche and the animal psyche. As if bringing a person closer to animals and “raising” the last ones to him, Darwin attributed to human beings human thoughts, feelings, imaginations, etc.

A one-sided understanding of the genetic relatedness of the psyche of man and animals was, as already noted, criticized by A. Wagner. Wagner emphasized that the comparison of the mental functions of animals should be carried out not with the human psyche, but with the psyche of the forms immediately preceding this group of animals and after them. At the same time, he pointed out the existence of general laws of the evolution of the psyche, without the knowledge of which the understanding of human consciousness is impossible. Such an evolutionary approach makes it possible to reliably reveal the prehistory of anthropogenesis, and in particular the biological prerequisites for the emergence of the human psyche.

At the same time, however, it is necessary to take into account that one can judge about the origin of human consciousness, as well as about the process of anthropogenesis in general, only indirectly, only by analogy with what we see in living animals. These animals, however, have gone a long way of adaptive evolution, and their behavior has a deep imprint of specialization to the special conditions of their existence.

If, for example, we take higher vertebrates, to which man is biologically related, then there are a number of side branches in the evolution of the psyche, not related to the line leading to anthropogenesis, but reflecting only the specific biological specialization of individual groups of animals. The most striking example is in this respect birds. The same applies to mammals, individual units of which embody a similar specialization to a specific way of life. And even with respect to primates, we must reckon with the same specialization, and the current living anthropoids, in the course of their development, from the extinct ancestors common to the human, not only did not approach the human, but, on the contrary, became distant. Therefore, they, apparently, are now at a lower mental level than this ancestor.

It also follows that all, even the most complex, psychic abilities of monkeys are entirely determined by the conditions of their life in their natural environment, their biology, and on the other hand, serve only to adapt to these conditions. Features of lifestyle determine the specific features of mental processes, including the thinking of monkeys.

All this is important to remember when it comes to finding the biological roots and prerequisites for the emergence of human consciousness. According to the behavior of the now existing monkeys and other animals, we can judge only about the levels and directions of mental development leading to man, and about the general laws of this process.

The problem of the origin of work

The evolution of haptic and sensory functions of higher mammals

It is well known that the decisive factor in the transformation of the animal ancestor - the fossil apes - into humans was discovered about a hundred years ago by F. Engels: the labor that created man created the human consciousness. Labor activity, articulate speech, and on their basis and social life determined the development of the human psyche and, thus, are the distinguishing criteria of human mental activity compared to that of animals. Therefore, in order to clarify the specific conditions for the emergence of consciousness, it is necessary to find in the animal world the possible biological causes of these forms of human activity and to trace the probable path of their development.

Labor from its very inception was tame, the original human thinking was just as necessary. In modern monkeys, as already noted, it remained a purely "manual thinking." The hand is an organ and a product of human labor: having developed from the monkey’s hand, becoming an organ of labor, the human hand reached thanks to labor, and only through labor, as Engels emphasized, “that high degree of perfection, on which it could, as if by the power of magic, cause the life of the painting by Raphael, the statue of Thorvaldsen, the music of Paganini ". [62]

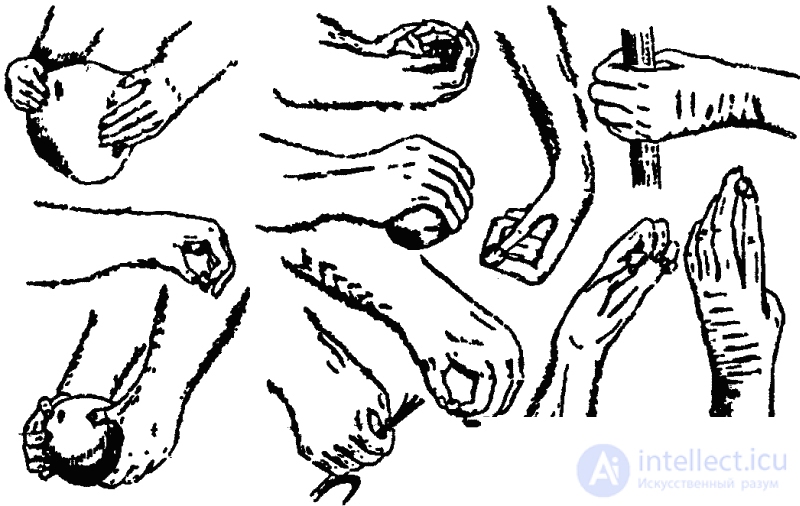

Thus, the hand (its development and qualitative transformations) occupies a central place in anthropogenesis, both physically and psychologically. In this case, the main role was played by her exceptional prehensile (haptic) abilities (Fig. 49). The biological prerequisites for the emergence of labor activity must, therefore, be sought primarily in the peculiarities of the prehensile function of the forelimbs of mammals.

Here we are confronted with a very interesting question: why, in fact, did monkeys become the ancestors of man? Why the beginning of the development of intelligent creatures could not give another group of mammals, especially since the grasping function is not a privilege only monkeys. In search of an answer to these questions, Fabry studied in a comparative aspect in the monkey and other mammals the relationship between the main (locomotor) and additional (manipulative) functions of the forelimbs and found that the antagonistic relationship between the main and additional functions of the forelimbs was crucial for the anthropogenesis process. The active participation of both forelimbs at the same time in handling objects in manipulation is associated with their frequent release from support and movement functions, which prevents specialization for long, fast running.

At the same time, with the reduction of the manipulative functions, the grasping abilities of the limbs suffer above all. As previously indicated, some of the additional functions of the front limbs are transferred to the oral apparatus. The least complementary, including prehensile, functions are suppressed in bears, raccoons and some other mammals (mainly predators and rodents), but here the evolution of motor activity was determined by the antagonism between the main and additional functions of their front limbs.

The only exception among mammals, according to Fabry, are primates. The main, and most importantly, the primary form of their movement consists in climbing by grabbing branches, and this form of locomotion constitutes thus the main function of their limbs. But this method of movement is associated with increased mobility of the fingers and the preservation of the opposition of the first finger to the rest, which harmoniously combines with the requirements imposed by the manipulation of objects. Therefore, in monkeys, and, moreover, only in them, the main and additional functions of the forelimbs are not in antagonistic relations, but are harmoniously combined with each other.

This circumstance is one of the most significant differences in the evolution of the primate motional activity. On the basis of the harmonious combination of manipulation functions with locomotion and their mutual strengthening, such a powerful development of those exceptional motor abilities that raised the monkeys over other mammals and laid the foundation for the formation of specific motor abilities of the human hand became possible.

As Fabry’s research further showed, due to the absence of antagonism between primate forelimb functions, they, again, unlike other mammals, haptic hand function developed simultaneously in two directions: 1) towards increasing the full grip of objects and 2) towards increasing flexibility and variability grasping movements. But only such a development could serve as a sufficient evolutionary basis for the emergence of the use of tools. This is one of the reasons (if not the main reason), why only a monkey could give rise to evolution towards humans.

It is also important to note that as a result of the special development of haptics in monkeys, “the human brush,” as the well-known Soviet anthropologist MF Nesturkh writes, “generally retained the basic type of structure from fossil anthropoids ... For the implementation of labor activities, the finest manipulations and workshops movements sufficient turned out to be a relatively small morphological transformation of the hand. ” [63]

These deep progressive transformations in the motor, especially the haptic, sphere, also confirmed by the data of evolutionary morphology and palerimatology, are associated with equally profound correlative changes in the entire behavior. First of all, this refers to the sensory functions, in particular, the skin-muscular sensitivity of the hand, which, as already noted, in primates acquires leading importance. A crucial point here is the interaction of tactile-kinesthetic sensitivity with vision, the interdependence of these sensory systems. I. Sechenov also emphasized the enormous importance of this interaction as a factor in the formation of human mental activity, in which, according to Sechenov, “the initial training and education of the senses” is carried out by muscular feeling and tactile sensitivity of the hand when combined hand movements with vision. This process is interrelated: as the vision is “learned” by the movement sensitivity of the hand, the movements of the hands themselves are increasingly controlled, corrected and controlled by vision. According to Fabry, in this respect, monkeys are an exception among mammals: only they have such relationships, which are also one of the most important prerequisites for anthropogenesis. It is impossible to imagine the birth of even the simplest labor operations without such interaction, without visual control over the actions of the hands.

It is important here that the tactile-kinesthetic-optical sensitivity of monkeys is a single complex sensory system (which also arose on the basis of the absence of antagonism between the functions of the pectoral limb). By themselves, the components of this system are quite well developed in other vertebrates. So, tactile-kinesthetic sensitivity is well developed, for example, in a raccoon, which is clearly manifested at least in the previously described opening of locking mechanisms. Under natural conditions, raccoons touch the sludge and aquatic plants in the water in search of food, as well as on land, and often makes groping movements. However, the monkeys far exceed them in the variety of finger movements, which produce the aforementioned practical analysis of food objects during their cleansing, dismemberment, etc. Voytonis saw this particular diet of monkeys (eating very different plant objects in their physical qualities) from the root causes of the development of their research orientation, their “curiosity”.

As for the view, then, as already mentioned, it is excellently developed in birds. But Engels' famous saying that “the eagle sees much farther than a man, but the human eye notices much more in things than the eagle’s eye”, [64] with extreme precision characterizes the essence of two fundamentally different paths of vision development. And only the vision of monkeys, which develops and acts in combination with the sensitivity of the hand, especially its extremely mobile fingers, has become capable of perceiving the physical properties of objects so fully that it is sufficient and at the same time necessary for the first people to carry out labor operations. That is why only the monkey's vision could turn into human vision.

Monkey activity

The specific embodiment of the interaction of vision and tactile-kinesthetic sensitivity of the hands is found in the extremely intense and diverse manipulative activity of monkeys.

Studies conducted by a number of Soviet zoopsychologists (Ladygina-Kots, Voytonis, Levykina, Fabri, Novoselova, and others) showed that both lower and higher (apes) monkeys carried out during the manipulation of a practical analysis of the object (dismemberment, parsing it, highlighting and inspection of individual parts, etc.). However, in apes much stronger than in lower ones, synthetic (“constructive”) actions are expressed, i.e., rebuilding from parts, the whole by approaching, joining, layering objects, twisting, wrapping, weaving, etc. Constructive actions occur naturally in chimpanzees in nesting.

In addition to the constructive activities of Ladigina-Kots, she also identified the following forms of activity that emerge during the manipulation of objects: tentative-examining (familiarizing), processing, motor-game, preserving the object, rejecting it, and instrumental activity. A quantitative analysis of the overall structure of chimpanzee activity during the manipulation process led Ladygin-Kots to the conclusion that, in relation to non-food objects, an exploratory (superficial familiarization with objects that do not leave noticeable traces) most often appears (processing (deepening the impact on an object - scratching, gnawing , dismemberment, etc.) and constructive activity. The least manifested tool activity.

Ladygina-Kots explains these differences in the specific weight of individual forms of the subject activity of chimpanzees by the peculiarities of the way of life of this anthropoid. A large place, which occupies an orienting survey and processing activity in the behavior of chimpanzees, is explained by the diversity of vegetable feed and the difficult conditions in which edible from inedible is distinguished, and also by the often complex structure of food objects (the need for their dismemberment, separation of edible or especially tasty parts of them) etc.).

Ladygina-Kots drew attention to the fact that, in contrast to nest-building, extra-nesting constructive activity is rare and well-developed. It manifests itself in conditions of bondage in entanglement, wrapping or interlacing, for example, twigs or ropes, or in rolling balls of clay. It is significant that such manipulation is not aimed at obtaining a certain result of activity, but, on the contrary, most often goes into deconstruction, i.e., destruction of the result of activity (unwinding, unwinding, dismemberment, etc.).

Chimpanzees have a minimal development of cannabis activity, that is, using the object as an aid to achieving any biologically significant goal, Ladygina-Kots explains by the fact that this form of handling objects is extremely rare under natural conditions.

Indeed, despite the intensive study of the behavior of apes in vivo, carried out by a number of researchers in recent years, only isolated instances of tool actions are known. Such observations include Lavik-Goodall described cases of extraction of termites from their buildings with the help of twigs or straws or collecting moisture from the recesses in the tree trunk with the help of chewed clump of leaves. В действиях с веточками наибольший интерес представляет то обстоятельство, что прежде чем пользоваться ими как орудиями, шимпанзе (как в описанных ранее опытах Ладыгиной-Котс) отламывают мешающие листья и боковые побеги.

Даже эти, хотя лишь изредка наблюдаемые, но, безусловно, замечательные, орудийные действия дикоживущих шимпанзе являются, однако, несравненно более простыми, чем орудийные действия, искусственно формируемые у человекообразных обезьян в специальных условиях лабораторного эксперимента. Это означает, что получаемые в экспериментальных условиях данные свидетельствуют лишь о потенциальных психических способностях этих животных, но не о характере их естественного поведения. Ладыгина-Котс расценивала, самостоятельное применение орудия скорее как индивидуальную, чем видовую черту в поведении высших обезьян. Правда, как показывают полевые наблюдения, такое индивидуальное поведение может при соответствующих условиях проявляться в более или менее одинаковой мере среди многих или даже всех членов одной популяции обезьян.

Во всяком случае следует постоянно иметь в виду биологическую ограниченность орудийных действий антропоидов и тот факт, что мы имеем здесь дело явно с рудиментами прежних способностей, с угасшим реликтовым явлением, которое может, однако, как бы вспыхнуть в искусственно создаваемых условиях зоопсихологического эксперимента.

Предтрудовая предметная деятельность ископаемых обезьян

Не переоценивая орудийную деятельность современных антропоидов, нельзя одновременно не усмотреть в ней свидетельство одной из важных биологических предпосылок антропогенеза.

Надо думать, что у ископаемых антропоидов — предков человека — употребление орудий было значительно лучше развито, чем у современных человекообразных обезьян. С этой существенной поправкой можно по предметной деятельности последних, а также низших обезьян в известной мере судить о развитии предтрудовой деятельности наших животных предков и о тех условиях, в которых зародились первые трудовые действия, выполняемые с помощью орудий труда.

В этой связи важно вспомнить слова Энгельса о том, что «труд начинается с изготовления орудий» [65] (курсив мой. — К.Ф.). Предпосылкой этому служили в свое время, очевидно, действия, исполняемые антропоидами, подобные наблюдаемым и у современных их представителей (удаление боковых побегов веточек, отщепление лучины от дощечки и т. п.). Однако изготовляемые таким образом обезьянами (как и другими животными) орудия являются не орудиями труда, а лишь средствами биологической адаптации к определенным ситуациям.

Уже «стремление манипулировать любым предметом, не имеющим даже отдаленного сходства с пищей, способность замечать детали и расчленять сложное, — все это, — пишет Войтонис, — является первой предпосылкой проявления умения пользоваться вещью как орудием в самом примитивном смысле этого слова». [66] Но если мы даже допустим, что ископаемые антропоиды обладали весьма развитой способностью к употреблению орудий, то все же остается неясным, почему эта биологическая способность могла и должна была «перерасти» в качественно иную деятельность — трудовую, а тем самым почему с необходимостью на земле появился человек.

Фабри пришел на основе своих исследований к выводу, что действительно в обычных своих формах предметная, в том числе орудийная, деятельность никогда не могла бы выйти за рамки биологических закономерностей и непосредственно «перерасти» в трудовую деятельность. Очевидно, даже высшие проявления манипуляционной (орудийной) деятельности у ископаемых человекообразных обезьян навсегда остались бы не более как формами биологической адаптации, если бы у непосредственных предков человека не наступили бы коренные изменения в поведении, аналоги которых Фабри обнаружил у современных обезьян при известных экстремальных условиях. Речь идет о явлении, которое он обозначил как «компенсаторное манипулирование». Суть его заключается в том, что в резко обедненной по сравнению с естественной среде (например, в пустой клетке) у обезьян происходит коренная перестройка манипуляционной активности. В естественных условиях (или близких к ним условиях вольерного содержания) обезьяну окружает обилие пригодных для манипулирования предметов, которые распыляют внимание животных и стимулируют их к быстрой перемене деятельности.

В условиях же клеточного содержания, когда почти полностью отсутствуют предметы для манипулирования, нормальная многообразная и «рассеянная» манипуляционная деятельность обезьян концентрируется на тех весьма немногих предметах, которыми они могут располагать (или которые им дает экспериментатор). В итоге взамен разнообразных рассеянных манипуляций со многими предметами в природе животные производят не менее разнообразные, но интенсивные, сосредоточенные, длительные манипуляции с одним или немногими предметами. При этом разрозненные двигательные элементы концентрируются, что приводит к образованию значительно более сложных манипуляционных движений.

Thus, the natural need of monkeys in the manipulation of many different objects is compensated for in a medium that is dramatically depleted in objective components by a qualitatively new form of manipulation - namely, “compensatory manipulation”.

Не вдаваясь в подробности этого сложного процесса, необходимо, однако, отметить, что только подобные новые, в корне измененные, концентрированные и углубленные действия с предметами могли служить основой зарождения трудовой деятельности. И если обратиться к фактическим природным условиям, в которых зародилось человечество, то оказывается, что они действительно ознаменовались резким обеднением среды обитания наших животных предков. В конце миоцена, особенно же в плиоцене, началось быстрое сокращение тропических лесов, и многие их обитатели, в том числе обезьяны, оказались в полуоткрытой или даже совсем открытой безлесной местности, т. е. в среде, несравненно более однообразной и бедной объектами для манипулирования. В числе этих обезьян были и близкие к предку человека формы (рамапитек, парантроп, плезиантроп, австралопитек), а также, очевидно, и наш непосредственный верхнеплиоценовый предок.

Вынужденный переход в новую среду обитания принес обезьянам, все поведение и строение которых формировалось в течение миллионов лет в условиях лесной жизни, немалые трудности, и большинство из них вымерло. Очевидно, как отмечает Нестурх, преимущества имели те антропоиды, которые смогли выработать более совершенную прямую походку на двух ногах (прямохождение) на основе прежнего способа передвижения по деревьям — по так называемой круриации. Этот тип локомоции представляет собой хождение по толстым ветвям на задних конечностях при более или менее выпрямленном положении туловища. Передние конечности лишь поддерживают при этом верхнюю часть тела.

Круриация, по Нестурху, лучше всего подготовила обезьян, сошедших на землю, к передвижению в более или менее выпрямленном положении без опоры на передние конечности, что оказалось биологически выгодным, так как эти конечности могли в результате больше и лучше использоваться для орудийной деятельности.

Из антропоидов, перешедших к жизни на открытых пространствах, уцелел, очевидно, один-единственный вид, который и стал непосредственным предком человека. Среди антропологов господствует мнение, что этот антропоид выжил, невзирая на резкое ухудшение условий жизни в начале плейстоцена, благодаря успешному использованию природных предметов в качестве орудий, а затем употреблению искусственных орудий.

Однако, как считает Фабри, такую спасательную роль, к тому же и преобразившую все поведение нашего предка и приведшую его к трудовой деятельности, орудийная деятельность смогла выполнить лишь после того, как она сама претерпела глубокую качественную перестройку. Необходимость такой перестройки была обусловлена тем, что развивавшаяся в условиях тропического леса — с его обилием разнообразных предметов — манипуляционная активность (жизненно необходимая для нормального развития и функционирования двигательного аппарата) должна была в условиях резко обедненной среды открытых пространств компенсироваться. Очевидно, тогда и возникли такие формы «компенсаторного манипулирования», которые привели к исключительно сильной концентрации элементов психомоторной сферы, что подняло орудийную деятельность нашего животного предка на качественно новую ступень.

Таким образом, высокоразвитая способность к компенсаторной перестройке предметной деятельности обеспечила выживание этого нашего предка и явилась необходимой основой для зарождения трудовой деятельности, а тем самым и появления на земле человека.

У обезьян же, оставшихся жить в лесах, естественно, не развивались компенсаторные движения, и для них были вполне достаточны прежние формы биологической адаптации, в том числе и в сфере предметной деятельности. Поэтому их орудийная деятельность осталась лишь одной из таких чисто биологических форм приспособления и не могла превращаться в трудовую деятельность. Вот почему употребление орудий у обезьян не прогрессировало, а лишь сохранялось у некоторых современных видов.

Орудия животных и орудия труда человека

Не вдаваясь в ход развития самой трудовой деятельности, отметим лишь еще несколько существенных моментов в дополнение к тому, что уже говорилось об орудийной деятельности обезьян.

Прежде всего, важно подчеркнуть, что орудием, как мы видели, может быть любой предмет, применяемый животным для решения определенной задачи в конкретной ситуации. Орудие труда же непременно должно специально изготавливаться для определенных трудовых операций и предполагает знание о будущем его применении. Они изготовляются впрок еще до того, как возникнет возможность или необходимость их применения. Сама по себе такая деятельность биологически бессмысленна и даже вредна (трата времени и энергии «впустую») и может оправдаться лишь предвидением возникновения таких ситуаций, в которых без орудий труда не обойтись.

Это значит, что изготовление орудий труда предполагает предвидение возможных причинно-следственных отношений в будущем, а вместе с тем, как показала Ладыгина-Котс, шимпанзе неспособен постичь такие отношения даже при подготовке орудия к непосредственному его применению в ходе решения задачи.

С этим связано и то важное обстоятельство, что при орудийных действиях обезьян за орудием совершенно не закрепляется его «рабочее» значение. Вне конкретной ситуации решения задачи, например до и после эксперимента, предмет, служивший орудием, теряет для обезьяны всякое функциональное значение, и она относится к нему точно так же, как и к любому другому «бесполезному» предмету. Произведенная обезьяной с помощью орудия операция не фиксируется за ним, и вне его непосредственного применения обезьяна относится к нему безразлично, а потому и не хранит его постоянно в качестве орудия. В противоположность этому не только человек хранит изготовленные им орудия, но и в самих орудиях хранятся осуществляемые человеком способы воздействия на объекты природы.

Более того, даже при индивидуальном изготовлении орудия имеет место изготовление общественного предмета, ибо этот предмет имеет особый способ употребления, который общественно выработан в процессе коллективного труда и который закреплен за ним. Каждое орудие человека является материальным воплощением определенной общественно выработанной трудовой операции.

Таким образом, с возникновением труда связано коренное изменение всего поведения: из общей деятельности, направленной на непосредственное удовлетворение потребности, выделяется специальное действие, не направляемое непосредственным биологическим мотивом и получающее свой смысл лишь при дальнейшем использовании его результатов. В этом заключается одно из важнейших изменений общей структуры поведения, знаменующих переход от естественной истории мира животных к общественной истории человечества. По мере дальнейшего развития общественных отношений и форм производства такие действия, не направляемые непосредственно биологическими мотивами, занимают в деятельности человека все большее и большее место и наконец приобретают решающее значение для всего его поведения.

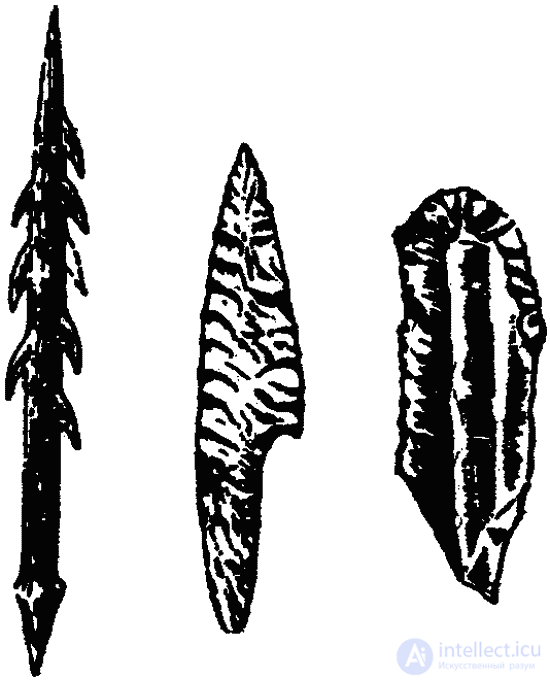

The genuine manufacture of tools implies that the object is not affected directly by the effector organs (teeth, hands), but by another object, i.e. the processing of the manufactured labor tools must be done by another tool (for example, stone). Findings of just such products of activity (chip off, chisels) are for anthropologists true evidence of our ancestors' work activity.

At the same time, according to Fabry, when manipulating biologically “neutral” objects (and only such could become tools) monkeys, although sometimes affecting one object on another (Fig. 24), pay attention to the changes that occur with the object. direct impact, i.e., with the “tool”, but not with the changes occurring with the “processed” (“second”) object, which serves no more than a substrate, “background”. In this respect, monkeys are no different from other animals. The conclusion suggests that these objective actions of monkeys are in their essence directly opposed to human labor activity, in which, naturally, the changes in the instrument of labor itself, which are not so important, are the changes in the object of labor (the homologue of the “second object”). Obviously, only in certain experimental conditions is it possible to switch the attention of monkeys to the “second object”.

However, the manufacture of tools (for example, cutting one stone with another) requires the formation of such specific methods of influence on the "second object", such operations that would lead to very special changes of this object, thanks to which only he will turn into a tool. A good example of this is the manufacture of the most ancient implements of labor of primitive man (stone hand saw, Fig. 50), where efforts were to be directed at creating a pointed end, i.e., the actual working part of the implement, and a wide, rounded top (nucleus, nucleus), adapted to firm holding of the weapon in hand. It was on such operations that the human consciousness grew.

It is quite natural that the creation of the first labor tools of the type of manual chopping of the Shell era, and even more so of the primitive tool (flakes) of the synanthropy from the pre-Jerusalem era, still went a long way to the manufacture of various advanced labor tools of the human type (neoanthropus) (Fig. 51). Even at the initial stage of the development of the neoanthropic material culture, for example, Cro-Magnon man, there is a huge variety of types of guns, including for the first time there are composite tools: dart tips, flint inserts, as well as needles, lancers and others. Particularly noteworthy are the abundance of tools for manufacture guns. Later, stone tools such as an ax or hoe appear.

Material culture and biological patterns

It is significant that, along with the powerful progress in the development of material culture and, consequently, of mental activity, the biological development of man has slowed down since the beginning of the late Paleolithic era: the physical type of man acquires a very great stability of his species characteristics. But among the most ancient and ancient people, the ratio was reversed: with extremely intensive biological evolution, expressed in great variability of morphological characters, the technology of making labor tools developed extremely slowly.

Based on this, the well-known Soviet anthropologist Ya. Ya. Roginsky advanced the theory of “two turning points” in human evolution (the phrase “a single jump with two turns” is also used). According to this theory, new, socio-historical patterns appeared among the most ancient people along with the birth of labor activity (the first turn). However, biological laws inherited from the animal ancestor continued to operate along with them for a long period. The gradual accumulation of new quality led at the final stage of this development to a sharp (second) turn, which consisted in the fact that these new, social patterns began to play a decisive role in the life and future development of people. This turn in the history of mankind was marked by the appearance of a man of the modern type - the neo-anthrop. Roginsky says on this occasion about the removal of the species-forming role of natural selection and the victory of social laws.

So, with the appearance of the neoanthropus in the late Paleolithic, the biological laws finally lose their leading meaning and give up their place to the public. Roginsky emphasizes that it was only with the advent of the neoanthropus that social patterns really acquired a dominant role in the life of human collectives.

This concept is consistent with the idea that the first labor actions were to be carried out even in the old (animal) form, represented, according to Fabry, by a combination of “compensatory manipulation” with the same instrumental activity enriched by it. Only later did the new content of objective activity (labor) acquire a new form in the form of specifically human labor movements, not peculiar to animals. Thus, at first, the outwardly simple and monotonous objective activity of the first people corresponded to the great influence of the biological laws inherited from the animal ancestors of man. And this, as it were, masked the accomplishment of the greatest event — the emergence of labor and with it the man himself.

The problem of the origin of public relations and articulate speech

Monkeys group behavior and the emergence of social relations

Social relations originated in the depths of the first forms of work. Work from the very beginning was collective, social. This resulted from the fact that people from the moment of their appearance on earth have always lived in groups, and monkeys - the ancestors of man - more or less large herds (or families). Thus, the biological prerequisites of human social life should be sought in the herd of fossil high primates, more precisely, in their objective activity performed in conditions of herd life.

On the other hand, labor determined from the very beginning the qualitative originality of the associations of the first people. This qualitative difference is rooted in the fact that even the most complex animal activity in animals never has the character of a social process and does not determine relations among community members, that even in animals with the most developed psyche the community structure is never formed on the basis of tool activity, does not depend on her, and especially not mediated by it.

All this must be remembered when identifying the biological prerequisites for the birth of human society. The attempts that are often made directly to deduce the laws of people's social life from the laws of animal group behavior are deeply flawed. Human society is not just a continuation or complication of the community of our animal ancestors, and social patterns are not reducible to the ethological patterns of the life of a monkey herd. Public relations of people arose, on the contrary, as a result of the breaking of these laws, as a result of a radical change in the very essence of herd life by the emerging labor activity.

In search of the biological prerequisites of social life, Voitonis turned to the herd life of lower monkeys in order to identify the conditions in which “the individual use of an instrument that appeared in individual individuals could become social, could influence the restructuring and development of relationships, could find in these relationships a powerful factor that stimulated the very use of the instrument. " [67] Voytonis and Tikh conducted in this direction numerous studies to identify the features of the structure of the herd and herd behavior in monkeys.

Tikh attaches particular importance to the emergence in monkeys of a new, independent and very powerful need for communicating with their own kind. This new need, according to Tikh, originated at the lowest level of the evolution of primates and reached its heyday in the living baboons, as well as in the apes living in families. In the animal ancestors of humans, the progressive development of herd instances also manifested itself in the formation of strong intrastate relations, which proved to be particularly useful when hunting together with natural tools. Tikh believes that it was precisely this activity that led to the need to process the hunting tools, and then to the manufacture of primitive stone tools for the manufacture of various hunting tools.

Tikh also attaches great importance to the fact that adolescents from the immediate ancestors of man obviously had to assimilate the traditions and skills developed in previous generations, learn from the experience of the older members of the community, and the latter, especially the males, should have shown not only mutual tolerance, but and the ability to cooperate, coordinate their actions. All this was required by the difficulty of joint hunting with the use of various objects (stones, sticks) as hunting tools. At the same time, at this stage, for the first time in the evolution of primates, conditions arose when there was a need to designate objects and without it it was impossible to ensure the coherence of the actions of members of the herd during a joint hunt.

Demo Modeling

Of great interest to understand the emergence of human forms of communication is described by Fabry "demonstrative manipulation" in monkeys.

In a number of mammals, cases have been described where some animals observe the manipulative actions of other animals. Thus, bears often observe the individual manipulation games of their relatives, and sometimes other animals, such as otters and beavers. However, this is most typical of monkeys, which not only passively observe the manipulations of another individual, but also react very animatedly to them. It often happens that one monkey "provocatively" manipulates in front of others. In addition to the demonstration of the object of manipulation and the actions performed with it, such a monkey often “teases” the other and moves the object to it, but immediately pulls it back and “attacks” it with a noise as soon as it reaches out to it. As a rule, this is repeated many times in a row. Such “teasing” with the subject often serves as an invitation to a joint game and corresponds to the similar “provocative” behavior of dogs and other mammals in “trophy” games (see ch. II, ch. 4), when “flirting” is performed by a “defiant” game object .

In other cases, the “deliberate” display of the object of manipulation leads the monkeys to a slightly different situation: one individual manipulated the object in full view of the members of the herd attentively watching its actions, and the aggressive manifestations of the “actor” that occur during normal “teasing”, suppressed by “spectators” by means of special “conciliatory” movements and poses. The “actor”, on the other hand, shows signs of “imposing”, characteristic of true demonstration behavior. This “demonstration manipulation” occurs predominantly in adult monkeys, but not in calves.

The result of the demonstration manipulation can be the imitative actions of the “spectators”, but not necessarily. It depends on how much the action of the "actor" stimulated the rest of the monkeys. However, the object of manipulation always acts as a mediator in communication between the “actor” and the “audience”.

During the demonstration manipulation, the “spectators” can familiarize themselves with the properties and structure of the object, which the “actor” manipulates without even touching the object. Such an acquaintance is accomplished indirectly: the assimilation of another's experience at a distance occurs by means of “contemplating” the actions of others.

Obviously, the demonstration manipulation is directly related to the formation of "traditions" in monkeys, described in detail by a number of Japanese researchers. Such traditions are formed within a closed population and encompass all its members. For example, in the population of Japanese macaques living on a small island, a gradual, but then general change in eating behavior was found, which was expressed in the development of new types of food and the invention of new forms of its pretreatment. According to published data, the conclusion is that it was based on mediated pups, and then demonstrative manipulation and imitative actions of monkeys.

Demonstration manipulation reveals all the signs of demonstration behavior (see Part I, Chapter 2), but it also plays an essential cognitive role. Thus, the demonstrative manipulation combines communicative and cognitive aspects of activity: “the audience” receive information not only about the manipulating individual (“actor”), whose actions contain elements of “imposing”, but also (distantly) about the properties and structure of the object of manipulation.

Demonstration manipulation was, according to Fabry, at one time, obviously, the source of the formation of purely human forms of communication, since the latter originated together with labor activity, the predecessor and biological basis of which was the manipulation of objects in monkeys. At the same time, it is precisely demonstration manipulation that creates the best conditions for joint communicative-cognitive activity, in which the main attention of community members is focused on the subject actions of the manipulating individual.

Animal language and articulate speech

In modern monkeys, the means of communication, communication, differ not only by their diversity, but also by pronounced addressing, an inducing function aimed at changing the behavior of members of the herd. Tikh also notes the greater expressiveness of the means of communication of monkeys and their similarity with the emotional means of communication in humans. However, unlike a person, as Tikh considers, monkey communication means - both sounds and gestures - are deprived of semantic function and therefore do not serve as an instrument of thinking.

In recent years, the communication capabilities of monkeys, especially apes, have been studied especially intensively, but not always by adequate methods. You can, for example, refer to the experiments of the American scientist D. Premac, who tried using the optical signal system to teach chimpanzees the human language. According to this system, the monkey developed associations between individual objects (pieces of plastic) and food, and the “sample selection” method was used, introduced into the practice of zoopsychological research in the 10s of our century by Ladygina-Kots: in order to receive a delicacy, the monkey must choose among different objects (in this case, various pieces of plastic) and give the experimenter the one that was shown to her before. In the same way, reactions to categories of objects were developed and generalized visual images were formed, representations similar to those with which we already became acquainted when considering the behavior of vertebrates and even bees, but, understandably, they were more complicated for chimpanzees. These were representations of the type “more” and “less”, “the same” and “different” and comparisons like “on”, “first”, “then”, “and”, etc., to which animals below anthropoids are likely are incapable.

These experiments, as well as similar experiments of other researchers, of course, very effectively show the exceptional abilities of apes to "symbolic" actions and generalizations, their great ability to communicate with a person and, of course, a particularly powerful development of their intelligence - all this, however, in especially intensive teaching influences from the person (“developmental education”, according to Ladygina-Kots).

At the same time, these experiments, contrary to the intentions of their authors, in no way prove that the anthropoids have a language with the same structure as humans do, if only because the chimpanzees “imposed” a similarity to the human language instead of establishing communication with animals using his own natural means of communication. It is clear that judging from the plastic language invented by Premak as the equivalent of a genuine monkey language, this will inevitably lead to artifacts. This way, in its very principle, is unpromising and cannot lead to an understanding of the essence of the language of the animal, because these experiments have given only a phenomenological picture of artificial communication behavior that looks like the manipulation of language structures in humans. У обезьян была выработана только лишь (правда, весьма сложная) система общения с человеком в дополнение к тому множеству систем общения человека с животным, которые он создал еще начиная со времен одомашнивания диких животных.

Итак, несмотря на подчас поразительное умение шимпанзе пользоваться оптическими символическими средствами при общении с человеком и в частности употреблять их в качестве сигналов своих потребностей, было бы ошибкой толковать результаты подобных опытов как доказательства якобы принципиального тождества языка обезьян и языка человека или вывести из них непосредственные указания на происхождение человеческих форм коммуникации. Неправомерность таких выводов вытекает из неадекватного истолкования результатов этих экспериментов, при котором из искусственно сформированного экспериментатором поведения обезьян выводятся заключения о закономерностях их естественного коммуникационного поведения.

Что же касается языковых возможностей обезьян, то принципиальная невозможность обучения обезьян членораздельному языку была

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 10 THE EVOLUTION OF PSYCHE AND ANTHROPOGENESIS

Часть 2 * * * - 10 THE EVOLUTION OF PSYCHE AND

Comments

To leave a comment

Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology

Terms: Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology