Lecture

Animal games and children's games (comparative psychological aspects) [72]

The games of animals have long been objects of intense zoopsychological and ethological research, but in the study of the comparative psychological aspects of the game today, in fact, little has changed since the times of the famous works of N. N. Ladygina-Kots. At the same time, the question of the possibilities (and necessity) of comparing games for young animals and children’s games is, of course, of great theoretical and practical interest, in particular, for child psychology and preschool pedagogy.

In this regard, here are some conclusions arising from the concept of the game of animals as a developing mental activity developed by us and the classification of animal games we proposed. According to this concept, animal games are not a special category of behavior, as is commonly believed, but the main content of a certain period of ontogenesis - juvenile (preadult, play), characteristic only of higher vertebrates (birds and mammals). In other words, a game is a set of specifically preadvual manifestations of the general process of the development of behavior in the ontogeny of animals, this is adual behavior in the process of its formation. In comparison with the previous, early postnatal period, the game constitutes a new content of behavior, which determines the maturation of the primary elements of behavior and their transformation into the behavior of adult (mature) animals.

At the same time, as shown by the results of the 35-year-old study of the manipulative behavior of different mammalian species that we cited, during the game not the behavioral acts of adult animals, but the sensorimotor components that make them develop. These components, the development of which began as early as the embryonic (prenatal) period of ontogenesis, undergo in the game period profound functional changes, and only in a qualitatively transformed form do they become the main parts of the “final” (adult) behavior. Consequently, it is not “just” that escalation of game actions into adults takes place, but the formation of a qualitatively new behavior of adult animals from the elements of these actions. This process of transformation of the sensorimotor components of behavior is accomplished on the basis of the accumulation of fundamental individual experience, which determines the cognitive function of the game in animals and in general the value of the game in the ontogeny of the animal psyche.

The mentioned functional transformations of the components of behavior correspond to general morphofunctional transformations and, like those, have the character of expansion, amplification or change of function. From the point of view of psychological analysis, the phenomena of substitution considered below are of most interest (replacement of objects of influence), since these transformations establish the most significant new connections with environmental components, which results in a qualitative enrichment of the content of mental reflection. It can even be said that, in general, the mental content of play activity, and thus the development of all mental activity in the juvenile period of ontogenesis, is determined by the establishment of different substitutional relations and connections with environmental components by young animals. They can be defined as “pre-adaptive-compensatory” connections that replace, anticipate and imitate life situations and relationships of adult animals. In this sense, all game activity is a preadaptive substitution of adult behavior.

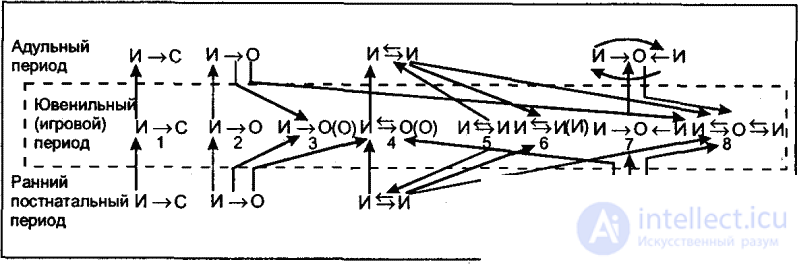

Based on the understanding of the game as a developing mental activity, we classified the game forms in animals precisely on the basis of the nature of their connections with the components of the environment, highlighting a number of categories of games. When describing them, we use the following conventions: And - the individual; And (I) - the individual, replacing the natural game partner; O - biologically significant object; 0 (0) - an object that replaces a biologically significant object; 0 (I) is the object that replaces the game partner; C - the substrate of gaming activity. The arrows indicate the connections that are actively established by the playing animals.

SINGLE (INDIVIDUAL) GAMES

Non-manipulation games

CATEGORY 1. Type I → C games. (Locomotion games; only direct connections of the individual with the substrate of gaming activity are established.)

Manipulation games

CATEGORY 2. Type I → O games. (Manipulation games with food, nest-building material, and similar biologically significant objects; direct connections of the individual with the object of the game are established.)

CATEGORY 3. Games of type I → O (O). (Connections similar to those in category 2 are established.)

CATEGORY 4. Games like I↔O (I). (Relationships similar to those in categories 2 and 3 are established, but sometimes there are also elements of feedback imitation.)

JOINT GAMES

Non-manipulation games

CATEGORIES Games like ISI. (Direct mutual relations are established with gaming partners.)

CATEGORY 6. Games such as AI (AND). (With a replacement game partner — an animal or a person — connections are made similar to those in category 5.)

Manipulation games

CATEGORY 7. Games of type I - O - I. (Correspond to games of category 2, but connections with the object are established simultaneously by two or more partners.)

CATEGORY 8. Games of type I = O = I. (Manipulation games in which the object, however, does not replace a biologically significant object or game partner, but serves as a means of communication between partners; between the latter, complex, generalized connections are established. )

Of course, in the specific behavior of young animals, the given categories are often found simultaneously in various combinations or pass into each other. For example, joint non-manipulation games, being locomotor in form, immediately within the same categories 5 or 6, become manipulative in form (more precisely, locomotor-manipulation) as soon as the game partners enter into physical contact with each other.

Of course, the essential difference lies in the fact that, unlike the “usual” manipulation of objects, the manipulation movements are directed here not just to the physical body, but to the active individual, the game partner responding to these movements also by manipulation actions, as a result What happens between the animals interaction in the conditions of communication. And this means that, within the general morphofunctional form common to all categories, a qualitatively new mental content has appeared, which makes it necessary to distinguish special categories 5 and 6. If an individual (playing partner) is considered as only a component of the environment, then the allocation of these categories superfluous, and they will completely fall into category 2. Psychic content plays no less clearly in compensatory manipulative games of categories 3 and 4. Thus, the proposed scheme reflects primarily the mental aspect s, mental vectors and connections of game activity of animals.

The substitutional transformations noted above manifest themselves in different categories in different ways and in varying degrees - they are most pronounced in compensatory games (categories 3, 4, 6). However, as already mentioned, all games are essentially substitutional, and therefore the game, no doubt, is the most labile that generally exists in the behavior of animals. Here, almost everything can be replaced and replaced, all animal activity is based on compensation, transposition, mediated effects (category 8) and other substitutional manifestations.

At the game stage of ontogenesis, the most important thing for a developing animal is to learn how to establish connections, “work out” this skill, and only then “clarify” the final (biologically significant) objects of influence and involve them in the scope of their (now directed) motor activity. While playing, a young animal must learn to establish various connections with the maximum biological effect, but with the least waste of time and effort, and moreover, in constantly changing external conditions, in conditions of constantly emerging situations of novelty. This is the meaning of the game for young animals.

From the above it follows that the game can only be called such a form of activity, which is characterized by signs of substitution. All components of juvenile behavior that lack such traits (for example, movements performed while eating) are, by their nature, persistent components of early postnatal behavior. At the juvenile stage of ontogenesis, these components undergo certain modifying (but not substitutional!) Changes under the influence of game activity and as a result, they become elements of the adult behavior of animals without significant qualitative transformations.

As a result, the following picture emerges. Initially established connections with the components of the environment (and the corresponding forms of mental reflection) are, though, elementary, primitive, but directly biologically effective and vital. The establishment of these connections (I - S, I - O, I = I) is the behavior "seriously". The same takes place with the appropriate establishment of links to adult animals, only this is already mature, developed behavior of a qualitatively higher level. The play activity of young animals that penetrates between them is the behavior “not seriously”, since it does not give a direct biological effect (due to the substitutional nature of the connections established).

Of course, along with game animals, vital links are also “seriously” established at the juvenile stage of development, which provide for their indigenous biological needs. But the juvenile period is different in that, along with such, “useless” connections are established directly, which determine the essence of this period. At the same time, the most important thing is that the formation of adult behavior, behavior “seriously”, occurs not by complicating the vital components of the behavior of a young animal, for example, eating (but not getting!) Food (these components only “ripen”), but by deploying and the improvement of just biologically “useless”, “not serious”, “trial” - in a word, substitutional game actions.

Adult behavior, therefore, does not “grow” directly and directly from the forms of early postnatal behavior; the process of straight-line development is interrupted here at the juvenile, game stage, and after a profound qualitative reorganization, the separated initial elements of behavior in a transformed, enriched, updated state are again grouped in the former directions of development (And –O, And = And, I –O –I). As a result, adult behavior is much more flexible, labile than the initial postnatal. That is why we call the game a developing mental activity.

All this applies, of course, only to higher vertebrates, and this is precisely the reason for the exceptional plasticity of their behavior. In other animals, adult behavior does directly “grow” out of primary postnatal behavior, which is formed in early postembryonic ontogenesis based on the maturation of innate components of behavior, innate recognition and early experience (primary obligate learning and elements of primitive optional learning). And a completely different kind of pattern of behavior development in animals undergoing metamorphosis (amphibians, insects, etc.) in ontogenesis, when already larval forms lead a kind of “adult” lifestyle (with the exception of reproductive function), which, however, differs radically from truly adult lifestyles of animal animals (imago). Thus, it is not necessary to talk about some "universal" patterns of behavior development in the ontogenesis of animals.

It is necessary to add to the characteristic of game activity that with the help of the classification system of manipulation elements developed by us it was established that during the transition from the early postnatal period to the juvenile appearance of gaming activity leads to a genuine leap in the motor sphere: the number of manipulative elements and the number of manipulative objects sharply increase. These quantitative changes in the treatment of animals with objects are associated with fundamental qualitative changes, which are reflected in the establishment of fundamentally new links with environmental components. Consequently, an increase in the number of elementary motor components of the behavior of the cub leads to a new quality of mental reflection.

It is also important to emphasize that the whole process of behavioral development (and, in connection with it, mental reflection) takes place in higher vertebrates in the form of negation: the primary connections established by the calf with the components of the world in the early postnatal period are partially replaced in the juvenile period by more complex, but temporary and biologically directly “useless”, substitutional play connections, which then (in adult animals) are also eliminated and replaced again by links of the original type, but filled qualitatively with vym content. These individual bonds, therefore, are homologous to elementary primary bonds, but are secondarily formed at a new, higher level. (Repeated qualitative changes, as already noted, occur within the limits of categories 1, 2 and 5, although there seems to be a “straightforward” development.)

The foregoing illustrates pic. 52, depicting the corresponding transitions from one “floor” of ontogenesis to another (the figures are the numbers of the categories of games, the other symbols are given above).

Thus, we see that, in higher vertebrates, the ontogeny of behavior and psyche is generally not a smooth continuous process, but due to the insertion of the game period, a process interrupted by a period of denial of the primary content. The validity of the proposed periodization of the ontogenesis of the mental activity of an animal with the release of a special, qualitatively excellent game period, due to which this dialectical discontinuity of the process of development of mental activity in the ontogeny of animals, is also confirmed.

When comparing games of animals with games of children, the researcher encounters the same difficulties as when comparing the behavior of animals and man in general. These difficulties arise because of the need to fully take into account the fundamental, qualitative differences in human behavior from that of even the most highly organized animals, such as chimpanzees. At the same time, the possibility and even the need for such a comparison are determined by the fact that human behavior, along with the leading socially determined, includes biological components and traits inherited from our animal ancestors, which are similar to their form to the same extent as higher animals. in which we share with them the structure and functions of the organism. These include, in particular, biological mechanisms of behavior (congenital triggers, processes of activity bias, imprinting, etc.), which determine in many respects the form of a series of important behavioral acts common to animals.

The main prerequisite for scientifically reliable comparison of human and animal behavior is that, for all comparative psychological studies, without exception, it is necessary first of all to proceed from a clear distinction between the form and content of behavior. The content of human behavior always differs qualitatively from that of animals, and these specifically human signs of its behavior arose as a result of anthropogenesis along with the birth of work, articulate speech and society, while the behavior of animals remained entirely biologically determined, never in any case went beyond the limits of biological laws, which determined the purely biological content of this behavior. Therefore, the content of the behavior of animals and humans is fundamentally incomparable, more precisely to say - only a comparative identification of differences is possible here.

Another thing is a form of human behavior, which in most cases, however, also underwent socially-conditioned qualitative changes in the course of historical development and as a result acquired specifically human traits, but in some cases retained a more or less animal-like appearance. Вот здесь и открывается плодотворное поле деятельности для сравнительной психологии, для выявления генетически обусловленных признаков сходства или даже общности в поведении животных и людей. Иными словами, если не считать некоторых примитивных поведенческих актов, сравнительно-психологический поиск общих для человека и животных признаков поведения (или признаков гомологического сходства) возможен только в отношении форм поведения, а также первичных сенсомоторных компонентов биологических механизмов поведения, но не его содержания.

Сказанное всецело относится и к сравнительно-онтогенетическому анализу поведения человека и животного, поскольку содержание поведения человека не только во взрослом состоянии, но и на всех этапах его постнатального развития качественно отличается от такового животных. Однако в некоторых случаях на начальных этапах онтогенеза это качественно новое, специфически человеческое, психическое содержание еще сохраняет некоторое время старую, унаследованную от наших животных предков и поэтому во многом общую с животными форму. Это сказывается и на общем ходе развития поведения.

Obviously, we are dealing here with a particular manifestation of a general pattern — the development of a new content with the original preservation of the old form before its replacement with a new adequate form. There is reason to believe that such ratios determined the initial stage of anthropogenesis, more precisely, the conditions for the birth of labor activity.

В некоторых ранних играх детей младшего возраста, которые только и можно сопоставить с играми детенышей животных, обнаруживаются определенные компоненты, гомологичные формам игровой активности детенышей высших животных, хотя содержание и этих игр уже социально детерминировано. У детей же более старшего возраста почти всецело специфически человеческими становятся и формы игры. Об этой специфике содержания детской игры, в частности, в раннем возрасте дают представление обстоятельные исследования М. Я. Басова, Л. С. Выготского, С. Л. Рубинштейна, А. Н. Леонтьева, Д. Б. Эльконина и труды других советских психологов, посвященные играм детей. Так, например, А. Н. Леонтьев усматривал «специфическое отличие игровой деятельности животных от, игры, зачаточные формы которой мы впервые наблюдаем у детей предшкольного возраста», прежде всего в том, что игры последних представляют собой предметную деятельность. Последняя, «составляя основу осознания ребенком мира человеческих предметов, определяет собой содержание игры ребенка». [73]

Важнейшие качественные отличия даже ранних игр детей связаны с активным сознательным воспитанием ребенка взрослыми в условиях постоянного общения с ним, его целенаправленным приобщением к искусственному миру предметов человеческого обихода и социальной ориентации его поведения. В этом же русле совершается и специфически человеческое овладение ребенком речью — процесс несопоставимый с развитием коммуникативных систем животных. Именно путем установления таких связей начинается передача от одного поколения к следующему общественно исторического опыта. При этом, как показала М. И. Лисина, общение ребенка со взрослым при их совместной игровой предметно-манипулятивной деятельности является важнейшим условием общего психического развития ребенка. Экспериментальную разработку и обстоятельный теоретический анализ разнообразных вопросов, связанных с процессом присвоения ребенком общественного опыта, осуществляли А. А. Люблинская, Н. Н. Поддъяков и другие психологи.

Не останавливаясь на конкретных играх детей и детенышей, рассмотрим лишь некоторые общие сравнительно-онтогенетические аспекты гомологического сходства форм развития поведения.

Признаки такого общего гомологического сходства проявляются прежде всего в том, что как у детенышей животных, так и у детей в ходе онтогенеза происходит глубокая перестройка устанавливаемых ими связей с компонентами окружающего мира, в корне меняется отношение к ним. И в том и в другом случае переход от доигрового к игровому периоду характеризуется трансформацией первичной двигательной активности, особенно при обращении с предметами, резко расширяется сфера предметной деятельности, качественно меняются способы манипулирования предметами и отношение к ним, причем как у животных, так и у детей эти изменения носят прежде всего субституционный характер (наряду с проявлениями расширения, усиления и смены функции).

Разумеется, структура процесса становления и развития игровой активности ребенка носит значительно более сложный характер, чем у животных. Об этом свидетельствуют, например, данные Р. Я. Лехтман-Абрамович, согласно которым доигровые предметные действия («преддействия») сначала переходят в «простые результативные повторные предметные действия», затем в «соотносимые действия», при которых ребенок выявляет пространственные соотношения. Эти игровые действия в свою очередь сменяются «функциональными действиями», которые характеризуются тем, что ребенок распространяет свою активность на новые предметы. В результате этого обобщается накопленный двигательный опыт, начинается (путем сравнения и различия) ознакомление с функциями объектов и устанавливаются некоторые простые и общие их признаки. Продолжением этого исследования служит работа Ф. И. Фрадкиной, посвященная выделению качественных различий между этапами развития уже самой игры в раннем детстве, которые в свою очередь являются предпосылкой развитой, творческой игры. Развитие структуры предметно-опосредованных действий ребенка в раннем детстве и изменение содержания опыта его деятельности были подробно изучены С. Л. Новоселовой.

Эта сложность, «многоступенчатость» хода развития, несомненно, обусловливает специфические особенности игры в дошкольном возрасте, причем в отношении не только ее наполнения социально детерминированным содержанием, но и развития особой структуры, адекватной сугубо человеческой форме игры дошкольников. В этой связи следует напомнить и о том, что А. В. Запорожец выделяет наряду с общевозрастным процессом развития процесс функционального развития, которое связано с овладением ребенком отдельными знаниями и способами действий, в то время как возрастное развитие характеризуется образованием новых психофизиологических уровней, формированием новых планов отражения действительности, изменением ведущего отношения ребенка к действительности, переходом к новым видам деятельности. Этим содержание психического развития ребенка, конечно, также в корне отличается от содержания этого процесса у детенышей животных. К тому же функциональное развитие, безусловно, протекает у первых в качественно совершенно иных формах, чем у последних.

Большой интерес представляет появление в ходе игровой активности обобщенного отношения к предметам и условность устанавливаемых при этом связей. «Игровое действие, — указывает А. Н. Леонтьев, — всегда обобщено, это есть всегда обобщенное действие». И далее: «Именно обобщенность игровых действий есть то, что позволяет игре осуществляться в неадекватных предметных условиях». [74] Правда, «в игре не всякий предмет может быть всем. Более того, различные игровые предметы-игрушки выполняют в зависимости от своего характера различные функции, по-разному участвуют в построении игры». [75] Как общую закономерность все это можно отнести к играм животных, которых также характеризует обобщенность отношения к игровым объектам (особенно в категориях 3, 4, 6 и 8). Однако эта общность форм обращения с предметами (и игровыми партнерами) кончается с появлением развитых детских игр с игрушками (в дошкольном возрасте), которые и имел в виду А. Н. Леонтьев. Эти игры уже качественно иные и по форме. К тому же у ребенка с самого начала формируется социально обусловленное обобщенное отношение к окружающему, чем определяется качественное отличие содержания даже самых ранних игр детей.

Что же касается отмеченного А. Н. Леонтьевым дифференцированного применения различных предметов в игровых действиях, то, в отличие от детей, у животных пригодность предмета служить «игрушкой» и конкретный способ его применения зависят от того, является ли данный предмет носителем того или иного ключевого раздражителя, т. е. детерминанты инстинктивного поведения. Иными словами, у высших животных развитие и совершенствование инстинктивных начал, их обрастание благоприобретаемыми компонентами, совершаются преимущественно путем упражнения с предметами, замещающими истинные объекты инстинктивных действий. Особенно наглядно это проявляется в играх категорий 3, 4 и 8, при которых ознакомление с миром осуществляется именно путем пробных действий с такими замещающими объектами, т. е. безопасными и бесполезными для «серьезных дел». Возможность такого преадаптационного «проигрывания» аналогов ситуаций предстоящей взрослой жизни обеспечивается тем, что оно выполняется в «зоне безопасности» — под защитой родительской особи.

Важно также подчеркнуть, что, по А. Н. Леонтьеву, на начальном этапе развития ребенка игра зарождается из предметных действий неифового типа и на первых порах является подчиненным процессом, зависящим от этих действий. Затем же игра становится ведущим типом деятельности, что связано с овладением «широким миром человеческих предметов». Тем самым перед ребенком открывается «путь осознания человеческого отношения к предметам, т. е. человеческого действия с ними». [76] Д. Б. Эльконии также указал на то, что доигровой период развития характеризуется первичной манипуляционной активностью, элементарными манипуляционными упражнениями, на основе которых возникают собственно игровые действия ребенка, определяемые Элькониным как действия с предметами, замещающими объекты поведения взрослых. Большое значение приобретает при этом также усложнение этих действий в сторону воспроизведения жизненных связей, характерных для определенных ситуаций жизни взрослых.

Если учесть отмеченные специфические особенности развития игрового поведения ребенка, то сопоставление с развитием игровой активности животных, отраженным в приведенной схеме, показывает, что существует определенное сходство в том, что и у детей и у детенышей высших животных диалектика развития поведения проявляется в субституционных преобразованиях, которые обусловливают замену устанавливаемых с компонентами среды первичных связей вторичными, «имитационными» и «суррогативными», т. е. игровыми связями, которые затем в свою очередь заменяются связями, присущими взрослому поведению.

В этих преобразованиях, в этом отрицании отрицания устанавливаемых связей, о котором уже говорилось выше, мы усматриваем общефункциональное значение игры, точнее, игрового периода, который возник на высших этапах эволюционного процесса как промежуточное звено между начальным, постнатальным и адультным этапами онтогенеза животных. Расчленение прежде непрерывного хода онтогенеза поведения промежуточным игровым периодом было на высшем уровне эволюции животного мира совершенно необходимо для дальнейшего прогрессивного развития психической деятельности высших животных, поскольку включение в онтогенез периода установления временных субституционных связей с компонентами среды обеспечило возможность существенного расширения диапазона активности и придания поведению большей лабильности, полноценного развития всех двигательных и познавательных возможностей в ходе многостороннего воздействия на компоненты окружающего мира и активного ознакомления с ним. Ясно, что такое коренное «расширение кругозора» на основе максимальной интенсификации двигательной активности являлось (и является) необходимой предпосылкой для усиленного накопления разнообразного жизненно важного индивидуального опыта.

В процессе своего становления человек унаследовал от своих животных предков это высокоэффективное, обладающее большой адаптивной ценностью достижение эволюции, и этим обусловлена гомологичность общего хода онтогенетического развития поведения у высших животных и у человека. Однако в онтогенезе человека открываются практически безграничные возможности многократного преобразования форм игровой активности, в то время как даже у наиболее развитых животных адультное поведение фиксируется в указанных нескольких конечных руслах, изображенных на схеме. Поэтому, хотя у человека поведение развивается отчасти по унаследованным от животных жестким руслам, оно в решающих сферах его деятельности не претерпевает на адультном этапе присущее животным сужение, а, наоборот, дивергентно развивается во все новых формах. В результате поведение человека развивается в конечном итоге в целом в значительно более широком диапазоне, чем на предшествующих этапах онтогенеза.

Не вдаваясь в подробности, мы коснулись здесь лишь некоторых сравнительно-онтогенетических аспектов развития поведения и психики животных и человека, опираясь при этом на нашу концепцию игры как развивающейся психической деятельности. Многие вопросы еще нуждаются в обстоятельном изучении, а приведенные здесь обобщения носят во многом предварительный характер. Разработка этой чрезвычайно сложной проблемы, без сомнения, имеет большое значение и для решения ряда насущных практических задач дошкольной педагогики.

Научное наследие А. Н. Леонтьева и вопросы эволюции психики [77]

Научное познание психики человека начинается с зоопсихологии. «Ясно, что исходным материалом для разработки психических фактов должны служить, как простейшие, психические проявления у животных, а не у человека», — подчеркивал еще 110 лет тому назад И. М. Сеченов, выделив эти слова в качестве одного из основных тезисов своего труда «Кому и как разрабатывать психологию». Правомерность этого требования и сейчас ни одним серьезным ученым не ставится под сомнение, более того, в наше время эта задача злободневна, как никогда. Познание психики невозможно без познания закономерностей ее становления и развития, без выявления ее предыстории и этапов развития психического отражения, начиная от его первичных, наиболее примитивных форм до высших проявлений психической активности животных и сопоставления последних с психическими процессами у человека. Эту поистине гигантскую задачу должна и призвана решать зоопсихология.

Of course, when studying these issues, the researcher faces incredible difficulties, in particular, it is very difficult to get an idea of the specific prerequisites and conditions for the emergence of human consciousness, the immediate history of the origin of work, articulate speech, human thinking and social life. After all, a zoopsychologist can rely on the behavior of only modern animals. But a comparative psychological analysis of their behavior and human behavior opens up quite real possibilities for solving the designated tasks and identifying the qualitative features and differences of the human psyche. It is only necessary to take into account that the history of mankind is an instant compared to the one and a half billion years of the development of animal life on earth, that as a result of this tremendous process of evolution a huge number of different biological categories appeared (and, accordingly, forms of mental reflection), that the evolutionary process did not develop linearly, but always in several parallel ways. In addition, the number of “ecological niches” on earth is immense, and it is precisely the ecological factors, the living conditions of the species that occupy these “niches” that determine, first of all, the peculiarities of their mental activity, and not their phylogenetic position. Therefore, the number of “typical representatives” that the zoopsychologist needs to be studied is enormous (not to mention that it is impossible to investigate the behavior of all animals: the number of zoological species is in the millions, but even, for example, there are more than 1,500 rodents alone!).

It follows that the primary task of zoopsychology is to establish, first of all, the most general laws and basic stages in the development of the psyche. A reliable basis for solving this problem is the theory of activity developed by Soviet psychologists. In this regard, Alexey Nikolaevich Leontyev made a great contribution to the development of general questions of mental reflection in animals. We mean, first of all, the well-known works of A. N. Leontiev “The Problem of the Origin of Sensation” and “An Essay on the Development of the Psyche”, first published in 1940–1947 and then included in his work "Problems of the development of the psyche", as well as posthumously published work "The Psychology of the Image." In the latter, he, in particular, pointed out that many problems of zoopsychology can be successfully resolved if we consider the adaptation of animals to life in the world around them as an adaptation to its discreteness, to the connections of things filling it, to their changes in space. Recall that in the "Outline of the Development of the Psyche" A. N. Leont'ev expounds his concept of the stage development of the psyche in the process of evolution of the animal world.

Developing his ideas, A.N. Leontiev proceeded from the fact that not only in humans, but also in animals, the psyche is "included" in external activity and depends on it, that "every reflection is formed in the process of an animal's activity." [78] He emphasized that the mental image is a product that practically connects the subject with the objective reality, that the animals ’reflection of the environment is in unity with their activities, that the mental reflection of the objective world is generated not by direct influences, but by the processes by which the animal enters practical contacts with the objective world: the object itself controls the primary activity and only secondarily its image as a subjective product of activity. According to A. N. Leont'ev, the emergence and development of the psyche is due to the fact that “the processes of external activity that mediate the relationships of organisms to the properties of the environment on which the preservation and development of their life depends are highlighted .” [79] At each new stage in the evolution of the behavior and psyche of animals, an ever more complete subordination of the effector processes of activity to objective relationships and the relations of the properties of objects that the animal enters into interaction arises. The objective world seems to be more and more “drawn in” into activity. According to A. N. Leont'ev, it is precisely the nature of these relations that determines "whether the object property affecting it will be reflected and how accurately the animal's sensations will be reflected in the animal's sensations." [80] At the same time, “the material basis for the development of the activity and sensitivity of animals is the development of their anatomical organization,” [81] that is, the morphological structures, in particular, the nervous system, develop along with the activity.

This leads to the conclusion that animal activity is a source of animal cognitive abilities and that “knowledge of the world” occurs in animals only in the process and as a result of an active impact on the environment, i.e. during the implementation of behavioral acts. The more developed, therefore, the motor capabilities of the animal, the higher its cognitive abilities. It can therefore be said that the level of mental reflection in certain animals depends on the extent to which they are able to influence the components of the environment, how diverse and deep these effects are, and this ultimately depends on the development of their motor apparatus. In this we see the embodiment of the theory of activity in zoopsychology and the significance of this theory for the successful solution of the problems of the development of the psyche of animals in the process of phylogenesis (as well as ontogenesis).

As A. N. Leontyev emphasized, when studying the origin and development of the psyche, it is necessary to take into account that the nervous system is not necessarily the material substrate of mental reflection. The unsatisfactory "neuropsychism", according to which the emergence of the psyche is associated with the appearance of the nervous system, according to A. N. Leont'ev, interrelated, but at the same time, their connection is not fixed, unambiguous, fixed once and for all, so that similar functions can be carried out by different bodies. ” [82] Therefore, it is impossible to put the emergence of the psyche "in a direct and unambiguous connection with the emergence of the nervous system, although at the subsequent stages of development this connection does not cause, of course, no doubt." [83] Thus, Leontyev approached the problem of the origin and development of the psyche with a deeply conscious understanding of the dialectical nature of this process: from the most primitive, rudimentary forms, the substrate of which is less differentiated matter - protoplasm, to the higher forms of mental reflection arising from differentiated nervous tissue. The conclusion suggests itself that the transition from, one can obviously say, “plasmatic” mental reflection to “nervous”, associated with the appearance of tissue structure in animal organisms, is a genuine dialectical leap, aromorphosis in the evolution of the animal world. There is no need to prove that such a dialectical-materialistic approach to the evolution of the psyche is fundamentally different from the flat-evolutionary, essentially metaphysical approach, in which the complication of animal behavior and psyche uniquely associates ONLY (and, moreover, often arbitrarily) with changes in the structure of the nervous system.

So, the approach to the problem of the origin and development of the psyche outlined by A. N. Leontiev leads to the conclusion that the presence of the nervous system is not the initial condition for the development of the psyche, and therefore mental activity appeared before nervous activity. Obviously, the latter has arisen at such a level of vital activity, when the implementation of vital functions has become so complicated that there is a need for such a special regulatory apparatus, which is the nervous system. Then, as an organ of mental reflection, the nervous system (more precisely, the higher parts of the central nervous system) became the necessary basis and prerequisite for the further development of the psyche. This complex question requires, of course, special consideration, which is beyond the scope of this article. We only note that the formation of the nervous system was determined by decisive functional changes (fundamental changes in the vital activity of organisms), that is, there was a primacy of function over form.

It is important to note A.N. Leontiev’s statement that “if animals did not exist to more complex forms of life, then the psyche would not exist, because the psyche is the product of the complication of life”, [84] that the character of mental reflection “ depends on the objective structure of animal activity, which practically connects the animal with the world around it. Responding to a change in the conditions of existence, the activity of animals has its own structure, its own, so to speak, “anatomy”. This creates the need for such a change in organs and their functions, which leads to the emergence of a higher form of mental reflection. ” [85] As we can see, A.N. Leontiev clearly defended the position about the primacy of function in the evolution of the psyche: the changed conditions of adaptation to the environment cause a change in the structure of animal activity, as a result of which the structure of organs changes and their functioning, which in turn leads to progressive development of mental reflection. In other words, A.N. Leontiev based his position on the concept of the development of the psyche that the essence of this process, its root cause and driving force is the interaction, which is the material life process, the process of establishing connections between the organism and the environment. Thus, A. N. Leont'ev extended to the sphere of mental reflection a certain position of Marxist philosophy that every property reveals itself in a certain form of interaction.

In A. Leontiev's developed periodization of the development of the psyche, covering the whole process of the evolution of the animal world, the stages of the elementary sensory psyche, perceptual psyche and intellect stand out. This was all the more significant because, with the exception of V. A. Wagner, the efforts of the Soviet zoopsychologists (N. Yu. Voytonisa, N. N. Ladygina-Kots, and others) were aimed at studying the monkey psyche and did not deal with lower levels of evolution. psyche. The concept of the psyche’s stadial development, proposed by A. N. Leontiev, was therefore a new word in science, especially against the background of the traditionally simplified and now unacceptable division into three supposedly consecutive “steps” - instinct, skill and intellect. The concept of A. N. Leont'ev is fundamentally different from this understanding of the essence of the evolution of behavior and the psyche, primarily because it is based on a non-formal sign of the division of all animal behavior into innate (supposedly “lower”) and acquired (“higher”). It is already well known that innate, instinctive behavior is no more primitive compared to individually acquired (learning), which, on the contrary, both of these components have evolved together, representing the unity of holistic behavior, and that accordingly in the higher stages of phylogenesis learning processes, and instinctive (genetically fixed) components of animal behavior.

Unfortunately, however, the above-mentioned simplistic, essentially metaphysical, ideas about the stages of the evolution of animal behavior, corresponding to the level of knowledge of the 20s, are sometimes presented to this day, especially in the work of some physiologists. So, for example, V. Detyer and E. Stellar offer even unknown by what quantitative data the drawn image of the curves, from which it is clear that the simplest are strong in taxis, the “simple” (?) Multicellular one appears, and at once “at full capacity”, reflexes, insects are overwhelmingly “instinctive” and “reflexive” animals, fish are mostly also but little capable of learning, birds are half “instinctive”, half “trained”, and mammals are fully trained. At the same time, one category supposedly replaces another: taxis seem to completely disappear in birds and lower mammals, reflexes and instincts lose all adaptive value in lower primates, which supposedly, like lower mammals, adapt through training and (primates) in part - thinking. All this is entirely contrary to modern knowledge about the behavior of animals. You can, for example, recall that taxis, these orienting components of any behavioral act, are inherent in the behavior of all animals, as well as humans.

The problems of the animal psyche do not tolerate oversimplification, and even more so “global” pseudo-solutions and amateurish attitudes, which are sometimes found in publications whose authors are far from zoopsychology, do not consider it necessary to take it into account, but rush to come up with superficial, often contrived sensational “explanations” . Only zoopsychology, which is primarily a science of the evolution of the psyche, can be carried on the task of scientific cognition of the laws of the psyche at all levels of phylogenesis, up to the approaches to the origin of human consciousness.

Sometimes they try to use the degree of complexity of the structure of the central nervous system as the decisive criterion for the evolution of the behavior and psyche of animals. In these cases, the morphological structure, supposedly determining the phylogenetic level and specificity of behavior, is taken as the initial one. Of course, in deciding questions of the evolution of the psyche, it is imperative to take into account the structure and functions of the nervous system of the animals studied (along with their other morphofunctional characteristics, for example, the musculoskeletal system). But, as we have repeatedly pointed out, the peculiarities of the macrostructure of the central nervous system, especially the brain, do not always correspond to the peculiarities of animal behavior, the level of their mental activity. It is enough to indicate, for example, birds, whose mental activity in terms of their development can be equated to that of mammals, while the brain in birds is deprived of the secondary cerebral arch — the gray cortex of the large hemispheres (neopallidum) containing the highest associative centers. Similarly, it affects with the complexity of its behavior, sometimes bordering on an intellectual one, a rat whose brain is very primitive in its structure: with a smooth surface of the big hemispheres devoid of furrows (the latter appear only among beavers, marmots and hares) among rodents and hares.

Nevertheless, the opinion is often expressed that progress in the evolution of animal behavior is primarily determined by morphological changes in the central nervous system (for example, an increase in the number of neurons as a result of mutation). It is absolutely clear that the opposite approach is the only true one, which recognizes the primacy of the function over the form (structure), an approach successfully implemented in Soviet evolutionary morphology. When addressing the development of the psyche (both in phylo- and in ontogenesis) and in general in any zoopsychological assessments, this means that morphological changes, which in turn are caused by changes in lifestyle, arise when the need arises to change new

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 Appendix Animal games and children's games (comparative psychological aspects)

Часть 2 * * * - Appendix Animal games and children's games

Часть 3 * * * - Appendix Animal games and children's games

Comments

To leave a comment

Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology

Terms: Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology