Lecture

Zoopsychology from ancient times to the creation of the first evolutionary theory. Currently, the science of animal behavior - zoopsychology - is experiencing a period of active development. Only in the last ten years, a number of new journals, as well as Internet sites devoted to the problems of zoopsychology, have appeared. Numerous articles are published in periodicals on biology and psychology that reflect the development of the main branches of this science.

The study of animal behavior has attracted the attention of scientists at all stages of the development of human society. The science of animal behavior was created and developed by scientists, who sometimes held diametrically opposed views on the nature of the same phenomena. Probably, in the way of studying these phenomena, in their interpretation all existing philosophical systems, as well as religious beliefs, were reflected.

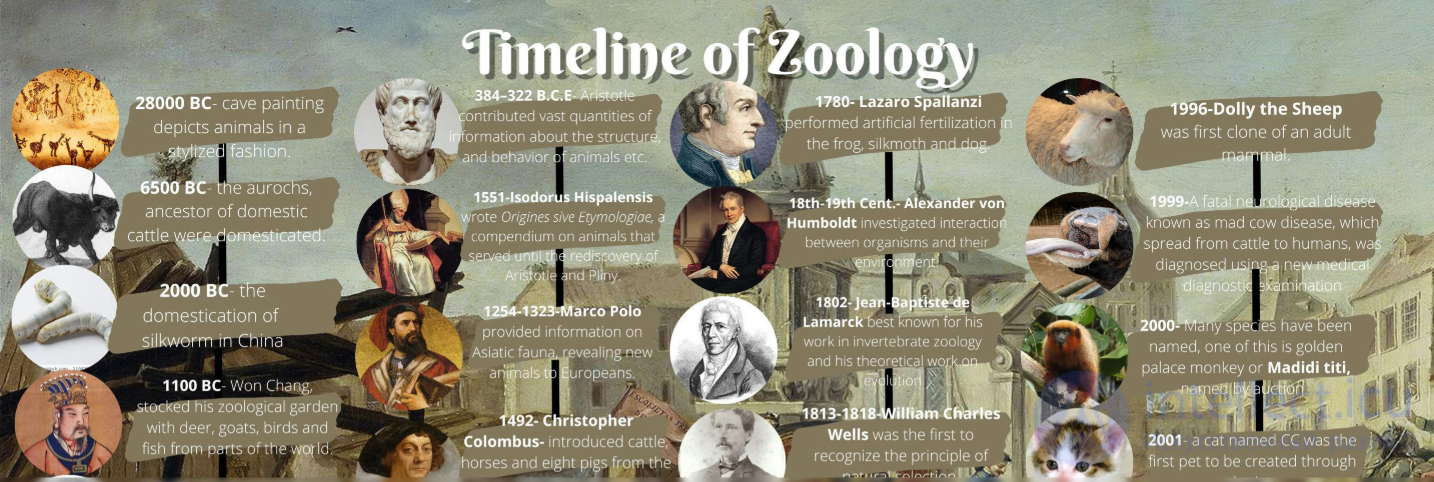

Traditionally, it is customary to divide the history of zoopsychology into two periods: 1) until Charles Darwin created the evolutionary theory in 1859; 2) the period after Darwin. By the latter period, the term “scientific zoopsychology” is often used, thus emphasizing that prior to the development of evolutionary theory, this science did not have a serious base and therefore could not be considered independent. Nevertheless, many prominent scientists of antiquity and the Middle Ages can rightfully be counted among zoopsychologists.

One of the main questions that occupied the minds of the researchers of antiquity, was the question of whether there is a difference between the complex activity of animals and reasonable human activity. It was about this issue that the first clashes of philosophical schools took place. Thus, the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus (341–270 BC) and his followers, especially the Roman poet, philosopher and scholar Lucretius (5th century BC., The main work “On the Nature of Things”), argued that the animal as well as man, he possesses a soul, but at the same time defended with all certainty the statement about the materiality of such a "soul". Lucretius himself has repeatedly said that the expedient actions of animals are the result of a kind of natural selection, since only animals with beneficial properties for the organism can survive in changing conditions.

In contrast to the views of the materialists, the ancient Greek philosophers Socrates (470–399 BC) and Plato (427–347 BC) regarded the soul as a divine phenomenon unrelated to the body. According to Plato, the soul is noticeably older than the body, and the souls of man and animals are different, since the soul of man has purely mental power. Only the lower form of the soul is inherent in animals - impulse, attraction. Later, on the basis of this worldview, the first ideas about instincts were formed. Most modern zoopsychologists are inclined to believe that the very idea of instinct was born on the basis of an idealistic opposition of the soul of man and animal.

The first naturalist among the philosophers of antiquity can rightly be called the ancient Greek scientist and philosopher Aristotle (485-423 BC. E., The treatise "On the Soul"). His views on the problems of the soul in humans and animals differed markedly from the views of predecessors. Aristotle attributed to man the immortal "rational soul" - the embodiment of the divine spirit. According to Aristotle, only the soul revives perishable matter (body), but only the body is capable of sensual impressions and inclinations. Unlike man, endowed with reason, the ability to know and free will, animals have only a mortal "sensual soul." However, Aristotle made a reservation for mammals, believing that all the animals with red blood and giving birth to living cubs have the same five senses as humans. Throughout life, the behavior of animals is aimed at self-preservation and procreation, but it is motivated by desires and drives, feelings of pleasure or pain. But among other animals, Aristotle believed, intelligent animals are also present, because the mind is expressed in different animals in varying degrees. Reasonable animals, besides the general behavioral traits inherent in animals as a whole, are capable of understanding the purpose of any of their actions.

The uniqueness of the teachings of Aristotle also lies in the fact that when studying the behavior of animals, he relied on specific observations. The ants, the study of which he was engaged for many years, the scientist noticed the dependence of their activity on external factors, in particular on lighting. He pointed to the ability to learn from a number of mammals and birds from each other, described the cases of sound communication of animals, especially during the breeding season. In addition, Aristotle first began conducting experiments on living objects, trying to better understand all the subtleties of animal behavior. For example, he noticed that after removing chicks from their parents, they learn to sing differently than the last, and from this they deduced that the ability to sing is not an acquired natural gift, but occurs only in the learning process.

Aristotle first began to separate the innate and acquired components of behavior. He noted in many animals the capacity for individual learning and memorization of what he learned, which he attached great importance to.

The teachings of Aristotle found a continuation and further development in the teachings of the Stoics, although in some respects significant differences are found here. The Stoics, in particular, the ancient Greek philosopher Chrysippus (280–206 BC.), Give the definition of instinct for the first time. They understand the instinct as a natural, purposeful attraction, directing the movement of the animal to the pleasant, useful and leading him away from the harmful and dangerous. The experiments with ducklings hatched by hen, which nevertheless at the moment of danger tried to hide in the water, were indicative. As other examples of instinctive behavior, Chrysippus referred to nest building and care for the offspring in birds, the construction of honeycombs in bees, and the ability of the spider to weave cobwebs. According to the Stoics, animals perform all these actions unconsciously, since they simply have no reason. Instinctive actions of animals are carried out without an understanding of the meaning of their activities, on the basis of purely innate knowledge. It is especially significant, according to the Stoics, that the same actions were performed by all animals of the same species in the same way.

Thus, already in the works of ancient thinkers, the main problems of animal behavior were touched upon: issues of innate and acquired behavior, instinct and learning, as well as the role of external and internal factors of mental activity of animals were discussed. Strangely enough, the most accurate concepts were born at the junction of two diametrically opposed areas of philosophy, such as the materialistic and idealistic understanding of the essence of mental activity. The teachings of Aristotle, Plato, Socrates and other thinkers of antiquity in many ways ahead of time, laying the foundation for zoopsychology as an independent science, although its true birth was still very far away.

Zoopsychology in the XVIII – XIX centuries The following significant studies in the field of zoopsychology were made only after a thousand-year hiatus, when in the Middle Ages the revival of scientific creativity began, but only in the XVIII century. The first attempts are made to study the behavior of animals on a solid foundation of reliable facts obtained as a result of observations and experiments. It was at this time that numerous works of prominent scientists, philosophers and naturalists appeared, which had a great influence on the further study of the mental activity of animals.

One of the first zoopsychologists can rightly be considered the French materialist philosopher, a physician by education J.-O. Lettetree (1709–1751) whose views later had a great influence on the scientific work of Ж-Б. Lamarck. According to Lamettra, instincts are a collection of movements that animals perform involuntarily, regardless of their thoughts and experience. Lettitri believed that the instincts are aimed primarily at the survival of the species and have a strict biological adaptation. He did not dwell on the study of the instinctive activity of certain species of animals, but tried to draw parallels by comparing the psychic abilities of various mammals, as well as birds, fish, and insects. As a result, Lamettri came to the conclusion about the gradual increase in mental abilities from simpler to more complex creatures and put him on top of this peculiar evolutionary ladder of man.

In the middle of the XVIII century. saw the light of the "Treatise on Animals" by the French philosopher and teacher E. B. Condillac (1715–1780). In this treatise, the scientist specifically addressed the issue of the origin of animal instincts. Noticing the similarity of instinctive actions with actions that are performed out of habit, Condillac concluded that instincts originated from rational actions by gradually turning off consciousness. Thus, in his opinion, the basis of any instinct is reasonable activity, which due to constant exercise became a habit, and only then turned into an instinct.

This point of view on the theory of instincts has caused heated debate. One of the most ardent opponents of Condillac was the French biologist Sh.Zh. Leroy. In his work “Philosophical Letters on the Mind and the Ability of Animals to Improve” (1802), which was released 20 years after the main work of Condillac, he advanced the task of studying the origin of the mind from the animal instinct as a result of the repetitive action of sensation and memory exercise. At the heart of the treatise Leroy lay long-term field studies. A keen naturalistic scientist, he persistently argued that the mental activity of animals and especially their instincts can be known only with comprehensive knowledge of their natural behavior and taking into account their lifestyle.

Simultaneously with Leroy, another great French naturalist J.L. Buffon (1707–1788, Histoire naturelle des animaux, 1855). By basing his research on field experience, Buffon was the first to interpret the results of his research correctly, avoiding anthropomorphic interpretations of behavior. Anthropomorphic scientists tried to explain the behavior of animals, endowing them with purely human qualities. In their opinion, animals may experience love, hate, shame, jealousy and other similar qualities. Buffon proved that this is not the case and that many animal actions cannot find adequate “human” explanations. According to the teachings of Buffon-animal, in particular, mammals, with whom the naturalist mainly worked, there are various forms of mental activity, such as sensations and habits, but not an understanding of the meaning of their actions. In addition, animals, according to Buffon, are able to communicate, but their language expresses only sensory experiences. Buffon insisted on the connection of environmental influences with the internal state of the animal, seeing in this the determining factor of his behavior. He drew attention to the fact that the mental qualities of an animal, its ability to learn, play the same, if not more important, role in the survival of the species, as well as the physical qualities. All concepts of Buffon, built on real facts, entered into a single system of natural science created by him and became the basis of the future science of animal behavior and psyche. In his later treatises, Buffon argued that the complex actions of animals are the result of a combination of innate natural functions that give the animal pleasure and habits. This concept, which was based on numerous field observations and experiments, in many ways anticipated the development of zoopsychology, giving food to the mind of future researchers.

The further development of zoopsychology as a science is closely connected with another area of biology - the theory of evolutionary theory. The actual task of biologists was to identify which traits are inherited and which are formed as a result of environmental exposure, which characteristic is universal, species, and which is individually acquired, as well as the significance of the various components of animal behavior in the process of evolution, where the line between man and animal. If up to this time, due to the dominance of metaphysical views in biology, the animal instincts seemed to be in an unchanged state from the moment of their occurrence, now, based on evolutionary theories, the origin of instincts could be explained and their variability could be explained using specific examples.

The first evolutionary teaching was proposed at the beginning of the XIX century. French naturalist J.-B. Lamarck (1744–1829, “The Philosophy of Zoology”). This doctrine was not yet a holistic, complete study and in many respects lost to later concepts of C. Darwin, but it was this that gave a new impetus to the further development of zoopsychology. Lamarck based his evolutionary concept on the concept of the guiding action of the psychic factor. He believed that the external environment acts on the animal organism indirectly, by changing the behavior of the animal. As a result of this impact, new needs arise, which in turn entail changes in the structure of the body through greater exercise by some and non-exercise of other organs. Thus, according to Lamarck, any physical change is based primarily on behavior, i.e., after E. B. Condillac defined mental activity as the basis of the very existence of the animal.

Lamarck argued that even the most complex manifestations of mental activity developed from simpler ones and should be studied in comparatively evolutionary terms. Nevertheless, he was a strict materialist and denied the existence of any special spiritual principle, not related to the physical structure of the animal and not amenable to natural science. All mental phenomena, according to Lamarck, are intimately connected with material structures and processes, and therefore these phenomena are knowable through experience. Lamarck attached particular importance to the connection of the psyche with the nervous system. According to many psychologists, it was Lamarck who laid the foundations of comparative psychology, comparing the structure of the nervous system of animals with the nature of their mental activity at different levels of phylogenesis.

Lamarck gave one of the first definitions of instinct, which for a long time was considered classical: “Animal instinct is an inclination that attracts (animal. - Avt.), Caused by sensations based on their needs and compels action without any participation of thought, without any participation will. "

Lamarck argued that the instinctive behavior of animals is variable and closely related to the environment. In his view, instincts arose in the process of evolution as a result of prolonged exposure to the body of certain agents of the environment. These directed actions led to the improvement of the entire organization of the animal through the formation of good habits, which were consolidated as a result of repeated repetition. Lamarck spoke about the inheritance of habits, and often even habits acquired within a single generation, since no one could yet give an exact answer on how much time was needed for an animal to develop this or that instinct. But at the same time, Lamarck argued that many instincts are extremely tenacious and will be passed down from generation to generation, until any fundamental change occurs in the life of a population. Lamarck saw in the instincts of animals not the manifestations of some mysterious supernatural force concealed in the body, but the natural reactions of the latter to the effects of the environment, which were formed in the process of evolution. At the same time, instinctive actions also have a pronounced adaptive character, since it is precisely the components of behavior that are beneficial to the body that were gradually consolidated. However, the instincts themselves were considered by Lamarck as variable properties of the animal. Thus, the views of Lamarck favorably differ from the views that have been encountered to the present day on instinct as the embodiment of some purely spontaneous internal forces, which initially have a reasonable direction of action.

Despite numerous shortcomings and mistakes, Lamarck's theory is a complete work, which later served as the basis for the largest studies of the human psyche and animals, carried out both by Lamarck's followers and his antagonists. It is difficult to overestimate the role of this great natural scientist as the founder of the materialist study of the mental activity of animals and the development of their psyche in the process of evolution. He largely ahead of his time and laid the foundations for further study of the evolution of mental activity, continued after some time by Charles Darwin.

The development of zoopsychology and the evolutionary theory of C. Darwin. The development of zoopsychology as a science cannot be imagined without the concepts of the evolutionary theory developed by C. Darwin (1809-1882). Only after the recognition of Darwin's theory in natural science did the idea of a single pattern of development in living nature and the continuity of the organic world become firmly established. Darwin paid special attention to the evolution of the mental activity of humans and animals. Thus, for his main work, The Origin of Species (1859), he wrote a separate chapter, Instinct, and at the same time, the fundamental work, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), and a series of separate articles on animal behavior were published. Darwin used a comparison of instincts in animals and humans, trying to prove their common origin on the basis of this comparison. He was the first biologist to distinguish rational actions associated with the experience of individual individuals from instinctive actions passed on by inheritance. Although Darwin avoided giving a detailed definition of instincts, he nevertheless emphasized that instinct is an action that is performed without prior experience and by many individuals in the same way to achieve a single goal. Comparing instinct with habit, Darwin said: "It would be a great mistake to suppose that a large number of instincts can originate from the habit of one generation and be transmitted hereditarily to subsequent generations."

Darwin emphasized the important role of natural selection in the formation of instincts, noting that during this process, an accumulation of changes beneficial to the species occurs, which continues until a new form of instinctive behavior arises. In addition, based on the study of external manifestations of the emotional state of a person, he created the first comparative description of instincts inherent in both animals and humans. Although the constant comparison of human and animal feelings looks like anthropomorphism from the outside, for Darwin it was a recognition of the common biological foundations of animal and human behavior and provided an opportunity to study their evolution.

In his studies, Darwin paid little attention to individual learning, since he did not recognize its essential significance for the historical process of the formation of instinctive behavior. At the same time, in his works, he often referred to the highly developed instincts of worker ants and bees, incapable of reproduction and, therefore, of passing on accumulated experience to offspring.

In his works "The Origin of Species" and "The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals," Darwin gave a well-founded natural-scientific explanation for the expediency of animal instincts. He classified instincts in the same way as he classified animal organ systems, emphasizing that natural selection preserves useful changes in innate behavior and eliminates harmful ones. This happens because any changes in behavior are associated with morphological changes in the nervous system and sense organs. It is these features of the structure of the nervous system, for example, changes in the structure of the cerebral cortex, that are inherited and are subject to variability along with other morphological features. The expediency of instincts, according to Darwin, is the result of natural selection.

Darwin also spoke about the hierarchy of instincts in his works. He believed that in the process of evolution, individual areas of the brain responsible for instinct lost the ability to respond to external stimulation in a uniform, i.e. instinctive, manner, and such organisms exhibit more complex forms of behavior. According to Darwin, instinctive actions are more prevalent in animals at the lower rungs of the evolutionary ladder, and the development of instincts directly depends on the phylogenetic rank of the animal. As later studies have shown, this interpretation by Darwin is not entirely correct, and the division of mental activity into uniform and variable components is very conditional, since in more complex forms of behavior any elements of behavior appear in a complex. Accordingly, at each phylogenetic level, these elements will reach the same degree of development. But it took more than one decade to understand this. Darwin's teaching itself is significant in the development of zoopsychology: for the first time, based on a huge amount of factual material, it was proven that the mental activity of animals is subject to the same natural-historical laws as all other manifestations of their life activity.

Darwin's evolutionary teaching was well received by many prominent scientists of the time: the German biologist E. Haeckel (1834–1919), the English biologist and the teacher T. Huxley (1825–1895), German physiologist, psychologist and philosopher V. Wundt (1832–1920), English philosopher and sociologist G. Spencer (1820–1903). Darwin’s views on instinct as innate behavior were supported by the American geneticist T.H. Morgan (1866–1945), D. Romens (1848–1894, The Mind of the Animals, 1888) and many other researchers who continued to develop this theory in their works.

Zoopsychology in Russia. One of the major Russian evolutionists who worked on the doctrine of instinct simultaneously with C. Darwin was Professor K. F. Roulier (1814-1858) of Moscow University. He was one of the first Russian scientists to oppose the idea of the supernatural nature of instinct. Roulier argued that instincts are an integral part of animal life and should be studied along with anatomy, ecology and physiology. Roulier especially emphasized the relationship between instincts and the environment of animals; he believed that their emergence and development are closely related to other manifestations of life, so the study of instincts is impossible without a comprehensive study of all its main manifestations. The origin of instincts and their further development, according to Roulier, was subject to general biological laws and was the result of material processes, the impact of the outside world on the organism. He believed that instinct is a specific reaction to environmental manifestations developed by living conditions, which has formed over the long history of the species. According to Roullier, the main factors in the origin of instincts are heredity, variability, and the increase in the level of organization of the animal in the historical process. Roullier also believed that the instincts of highly developed animals can change in the process of gaining new experience. He especially emphasized the variability of instincts along with the physical qualities of animals: “Just as cattle degenerate, as the qualities of a pointer dog, untrained, become deaf, so the need to fly away for birds, for some reason not having flown away for a long time, can be lost: domestic geese and ducks have become sedentary, while their wild relatives are constantly migratory birds. Only occasionally does a domestic drake, having strayed from home, begin to go wild while his mate is sitting on eggs, take off and join the wild ducks; only occasionally does such a feral drake fly away in the fall with his relatives to a warm country and the following spring will again appear in the yard where he hatched.”

As an example of a complex instinct that changes throughout the life of an animal, Roulier cited the migration of birds. At first, birds fly only due to instinctive processes that they learned from their parents, and, guided by adults in the flock, they fly away before the onset of cold weather, but gradually, accumulating knowledge, they themselves can lead the birds, choosing the best, most peaceful and food-rich places for migration.

It should be especially noted that Roulier tried to fill each example of the use of instinct with specific content; he never used this term without scientific evidence, which was often the case with scientists of that time. He obtained this evidence during numerous field studies, as well as experiments, in which he focused on identifying the role and interaction of environmental factors and physiological processes. It was thanks to this approach that Roulier's works took a leading place among the works of natural scientists of the mid-19th century.

Further work on the study of instincts, which served to form zoopsychology as a science, dates back to the beginning of the 20th century. It was at this time that the fundamental work of the Russian zoologist and psychologist V.A. Wagner (1849-1934, "Biological Foundations of Comparative Psychology", 1910-1913) was published. The author, based on a huge amount of material obtained both in the field and in numerous experiments, gave a deep analysis of the problem of instinct and learning. Wagner's experiments affected both vertebrates and invertebrates, which allowed him to draw conclusions about the origin and development of instincts in different phylogenetic groups. He came to the conclusion that the instinctive behavior of animals arose as a result of natural selection under the influence of the external environment and that instincts cannot be considered immutable. According to Wagner, instinctive activity is a developing plastic activity, subject to change under the influence of external environmental factors. As an illustration of the variability of instinct, Wagner cited his experiments with nest-building in swallows and weaving of webs in spiders. Having studied these processes in detail, the scientist came to the conclusion that, although instinctive behavior is subject to change, all instinctive actions occur within clear species-typical frameworks; it is not the instinctive actions themselves that are stable within a species, but the radius of their variability.

In the following decades, many Russian scientists conducted research on the variability of instinctive behavior in animals and its connection with learning. For example, the Russian physiologist, a student of I.P. Pavlov, L.A. Orbeli (1882–1958) analyzed the plasticity of animal behavior depending on the degree of their maturity. The Russian ornithologist A.N. Promptov (1898–1948), who studied the behavior of higher vertebrates (birds and mammals), identified integral conditioned reflex components in their instinctive actions that are formed in the process of ontogenesis, i.e., the individual development of an individual. It is these components, according to Promptov, determine the plasticity of instinctive behavior (for more details, see 2.1, p. 27). And the interaction of innate behavioral components with conditioned reflexes acquired on their basis during life produces species-typical behavioral features, which Promptov called a "species stereotype of behavior." Promptov's hypothesis was supported and developed by his colleague, the Russian ornithologist E.V. Lukin. As a result of experiments with passerine birds, she proved that young females nesting for the first time in their lives build nests characteristic of their species. But this stereotype can be violated if environmental conditions are atypical. For example, the spotted flycatcher, which usually builds nests in half-hollows, behind loose bark, in the absence of such shelters can build a nest on a horizontal branch, and even on the ground. Here, the modification of the nest-building instinct is traced in relation to the location of the nest. Modifications can also be observed in the replacement of nest-building material. For example, birds living in large cities can use completely unusual materials as nest-building materials: cotton wool, tram tickets, ropes, gauze.

Employees of the laboratory of the Polish zoopsychologist R.I. Voytusyaka K. Gromysh and M. Berestynska-Vilchek conducted studies of the plasticity of insect building activity. The first research results were published in the 1960s. Their objects were the caterpillars of the species Psyche viciella, in which they studied the process of building a cap, and the species Autispila stachjanella, in which they studied the plasticity of instinctive behavior in arranging moves in the leaves and cocoons. As a result of numerous experiments, scientists have discovered a huge adaptive variability of instinctive actions, especially when repairing the structures of these insects. It turned out that when repairing houses, the instinctive actions of caterpillars can vary significantly depending on changes in environmental conditions.

Promptov's research, despite their scientific significance, did not provide an objective understanding of such a complex process as the instinctive activity of animals. Promptov was certainly right when he emphasized the importance of the fusion of innate and acquired components in all forms of behavior, but he believed that the plasticity of instinct is provided only by individual components of the behavioral act. In fact, as Wagner noted, here we are dealing with categories of instinctive behavior that are different in size and importance. In this case, there is a change in the innate components, which is manifested in the individual variability of behavior typical of the species, and modification under extreme conditions of instinctive behavior. In addition, there are both acquired and therefore the most diverse forms of behavior, in which the dominant role is already played by various forms of learning, which are closely intertwined with innate components of behavior. All of this was described in detail in his writings by Wagner, and the experiments of Promptov only illustrated the complexity and ambiguity of the formation and development of instinctive behavior in animals.

Another major Soviet zoopsychologist beginning of XX century. was academician A.N. Severtsov (1866-1936). In the works Evolution and the Psyche (1922) and The Main Directions of the Evolutionary Process (1925), he deeply analyzed the fundamental difference between the variability of instinctive and acquired behavior (for more information, see 2.1, p. 28).

In the 1940-1960-ies. Zoopsychology along with genetics in our country was declared pseudoscience: numerous laboratories were closed, scientists were subjected to mass repressions. Only since the mid 1960s. began its gradual rebirth. It is primarily associated with the names of such major zoopsychologists as N.N. Ladygina-Kots (1889–1963) and her pupil K.E. Fabri (1923–1990), who developed a course of lectures on zoopsychology and ethology for the Faculty of Psychology at Moscow State University. The main subject of Fabry's work is related to the study of ontogenesis of the behavior and psyche of animals, the evolution of the psyche, the mental activity of primates, the ethological and biopsychological premises of anthropogenesis. Fabri is the author of the first and to the present time practically unsurpassed textbook on zoopsychology, which since 1976 has already withstood three reprints. It was thanks to K. Fabri that numerous works on zoopsychology and ethology were translated into Russian, including the classical works of K. Lorenz and N. Tinbergen - the founders of modern ethology.

In 1977, a small laboratory of zoopsychology was organized on the basis of the Department of Psychology at Moscow State University. Currently, the faculty defended several dissertations devoted to the orientation and research activities of animals, the study of the motivation of animal games, a comparative analysis of the manipulative activity of different mammalian species, the ontogenesis of the intelligence of anthropoids (apes). Conducted classical studies on the anthropogenesis and evolution of the psyche of apes and humans. Conducted and applied research, the beginning of which put another K. Fabri. This, for example, has become a classic study of the psychology of fish, which for the first time allowed to change the traditional attitude to fish - the object of fishing. This study showed that fish are animals with a sufficiently high level of perceptual development of the psyche, and are able to subtly adapt to the conditions of the fishery.

The faculty continues pedagogical activities, textbooks and anthologies — practically the only educational materials on zoopsychology in our country.

Comments

To leave a comment

Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology

Terms: Comparative Psychology and Zoopsychology