Lecture

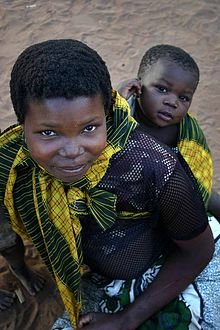

For babies and toddlers, to start a behavioral system of establishing attachment is to achieve intimacy with some important human figure, usually with parents.

Attachment theory is a psychological model that attempts to describe the dynamics of long-term and short-term interpersonal relationships. However, “attachment theory is not formulated as a general relationship theory. It affects only their specific facet ”[1]: how people react to pain in relationships, for example, when danger threatens their loved ones or when they are separated. In essence, affection depends on a person’s ability to develop a basic trust in himself and significant others. [2] In newborns, attachment as a behavioral motivational system guides the child to seek intimacy with significant adults, when they are alarmed, expecting them to receive protection and emotional support. John Bowlby believed that the tendency of primate babies to develop affection for significant adults was the result of evolution, because attachment behavior would make it easier for a child to survive in the face of dangers such as predation and the like. [3]

The most important principle of attachment theory is that for successful social and emotional development, and in particular, in order to learn how to effectively regulate their feelings, the child must develop relationships with at least one significant adult. Fathers and other adults are equally likely to become major figures if they provide the bulk of the care for the child and provide him with enough social experience. [4] In the presence of a sensitive and responsive adult, the child will use it as a “reliable base” for exploring the world of interpersonal relationships. It should be recognized that “even very sensitive significant adults understand the child’s signals only about 50 percent of the time. Their communication is either not synchronized or does not match at all. There are different cases when parents are tired or distracted. In the house the phone rings or you need to cook breakfast. In other words, the interaction process is disturbed quite often. But an adult should always remember that these difficulties are surmountable and can always be corrected. "[5]

Attachment between children and their significant adults is formed, even if this significant adult is not attentive and responsive with social interactions. [6] This has important implications. Newborns do not have the ability to leave unpredictable or cold relationships. Instead, they must adapt to such relationships. Studies of the age psychologist Mary Ainsworth (based on her draft protocol “The Strange Situation”) in the 1960s and 1970s found that children will have different attachment patterns, primarily depending on what their early experiences with meaningful adults. Early attachment patterns form — but by no means determine — the individual's expectations in subsequent relationships. [7] As a result, four different types of attachment were identified: reliable, avoidant, alarmingly ambivalent, disorganizing. Attachment theory has become the dominant theory used today in studying the behavior of infants and toddlers and in the field of children's mental health, the treatment of children, as well as in related fields. Reliable affection is when children feel that they can rely on meaningful adults to meet their needs for intimacy, emotional support and protection. This style of attachment is considered the most healthy and effective. The fear of separation is what babies feel when they are isolated from their meaningful adults. Anxiously ambivalent attachment is one in which a baby feels threatened by separation when separated from a meaningful adult, but when the caregiver returns to the baby, he does not feel calm and safe. Avoiding style is when a child, accordingly, avoids parents. A disorganizing type is formed when there is a shortage of the construct of attachment behavior itself. In the 1980s, the theory began to spread to adults. Attachment also applies to adults when they feel a close relationship with their parents and romantic partners.

Attachment system serves to achieve and maintain proximity to a meaningful adult. In close physical proximity, this system is not activated, and this allows the infant to focus its attention on the outside world.

As part of attachment theory, the term “ attachment” means “biological instinct in which a child begins to look for closeness to a significant adult when he feels threatened or uncomfortable. Attachment-based behavior awaits a response from a meaningful adult who is able to remove this threat or discomfort. ”[8] [9] Such connections can be reciprocal between two adults, but between a child and a significant adult, these connections are based on the child’s need for safety, security and protection. These needs are paramount in infancy and childhood. John Bowlby notes that organisms at different levels of phylogenetic development regulate instinctive behavior in various ways, ranging from primitive reflex-like fixed patterns to a comprehensive plan of target hierarchy, motive, and strong learning ability. In the most complex organisms, instinctive behavior can be corrected with the help of goal-setting with constant adjustments in real time (As, for example, the bird of prey corrects its own depending on the movement of prey). The concept of cybernetically controlled hierarchically organized behavioral systems, (Miller, Galanter, and Pribram, 1960), thus, replaced Freud's concept of drives and instincts. Such systems regulate behavior in ways that should not be strictly innate, but — depending on the organism — can adapt to a greater or lesser degree to environmental changes, provided that they do not deviate too much from the evolutionary adaptability of the organism itself. Such flexible organisms pay a price because adaptive behavioral systems can be easily overthrown. According to Bowlby, for humans, an environment of evolutionary adaptability probably resembles a society of hunter-gatherers whose goal is survival, and, ultimately, genetic replication. [10] Attachment theory is not an exhaustive description of human relationships, nor is it synonymous with love and affection, although these relationships may indicate that bonds exist. [10] Some babies delegate attachment attitudes (seek closeness) to more than one significant adult at the same time as discrimination between caregivers begin to show; most do so in the second year of life. The figures of significant adults are arranged hierarchically, and the main one is on top. [11] The main goal of the attachment behavioral system is to maintain a meaningful adult in accessibility. [12] “Threat” is the term used to activate the behavioral system of attachment caused by the fear of danger. “Anxiety” - a premonition or fear of being cut off from a meaningful adult. If it is unavailable or does not respond, an experience of separation grief arises. [13] In infants, physical separation can cause anxiety and anger, accompanied by sadness and despair. By the age of 3 or 4 years, physical separation is no longer so dangerous for a child to communicate with a significant adult. Security threats to older children and adults arise from a long absence, serious disruptions in communication, emotional inaccessibility, or signs of rejection or abandonment. [12]

Patterns of unsafe attachment can jeopardize interest in the outside world and the achievement of self-confidence. A child with a safe attachment type can freely concentrate on what surrounds him or her.

The behavioral attachment system serves to achieve and maintain proximity to a meaningful adult. [14] The behavior of prejudice appears in the first six months of life. In the first phase (the first eight weeks), babies smile, babble and cry to attract the attention of potential close adults. Although babies of this age learn to distinguish between these adults, this behavior is directed at everyone in close proximity. During the second phase (from two to six months), the baby learns more and more to distinguish between familiar and unfamiliar adults, becomes more responsive to a meaningful adult; stalking is added to the range of conduct. Sustained attachment develops in the third stage, at the age of six months to two years. In an infant, the reaction to a close adult becomes organized on a targeted basis, in order to achieve conditions that help it feel safe. [15] By the end of the first year of life, the child is able to display a spectrum of attachment behavior designed to maintain intimacy. This is manifested as a protest to the care of a close adult, the joy at his return, the child will also cling when frightened, and follow the adult whenever possible. [16] With the development of locomotion, the child begins to use meaningful adults as a “reliable base” for exploring the world. [15] Intelligence is the most unfolding when the child's attachment system is relaxed, and there is complete freedom. If a significant adult is unavailable or unresponsive, attachment behavior becomes more pronounced. [17] Anxiety, fear, illness, and fatigue will cause the child to increase attachment behavior. [18] After the second year, as the child begins to see the significant adult as an independent person, a more complex type of partnership is formed. [19] Children begin to notice other people's goals and feelings and plan their actions in accordance with them. For example, while babies cry because of pain, two-year-old children cry to call for a meaningful adult, and if this does not work, cry louder, shout, or follow him.

Usually, the attachment behavior and emotions observed in most social primates, including humans, are adaptive. The long evolution of these species included a set of social behaviors that made individual or group survival more likely. Often observed attachment behavior in babies remaining near familiar people would have safety benefits in terms of initial adaptation, and has similar benefits today. Bowlby believed that the environment of early adaptation resembles the modern environment of a hunter-gatherer society. [20] There is an indisputable advantage for survival, which is manifested in the ability to pick up potentially dangerous states, such as foreignness, loneliness or fast approach. According to Bowlby, finding intimacy with a meaningful adult in the face of a threat is the basic purpose of the attachment behavioral system.

Early experiences with significant adults gradually give rise to a system of thoughts, memories, beliefs, expectations, emotions, and behaviors regarding themselves and others.

Bowlby initially identified a sensitive period, during which attachments are formed from six months to two or three years, later these figures were changed by later researchers. These researchers have shown that there really is a sensitive period during which attachments will be formed, if possible, but the timeframes themselves are wider, and the effect is less stable and irreversible than originally proposed by Bowlby. In further research, the authors, discussing the theory of attachment, came to the conclusion that social development depends on both early and late relationships. The first steps in building affection will be easier if the child has one significant adult, or the occasional care of a small number of other people. According to Bowlby, many children have more than one significant adult to whom they direct attachment behavior. These figures are not equal; there is a strong bias, so that the attachment behavior is directed primarily towards one particular person. Bowlby used the term monotropy to describe this shift. [21] Researchers and theorists have already abandoned this concept, since this may mean that relationships with a close adult are qualitatively different from relationships with other people. Most likely, modern thinking postulates a certain hierarchy of relationships. [22] [23]

Early experiences with significant adults gradually form a system of thoughts, memories, beliefs, expectations, emotions and behavior in relation to themselves and others. This system, called the “internal working model of social interactions,” continues to evolve with time and experience. [24] Internal models regulate, interpret and predict the behavior associated with attachment within oneself and with significant adult. While they evolve according to changes in the environment, they are endowed with the ability to reflect and report on past and future attachment relationships. [7] They allow the child to lead new types of social interactions; knowing, for example, that the infant should be treated differently than the older child, or that interaction with teachers and parents has similar features. This internal working model continues to develop to a mature age, helping to cope with friendship, marriage and parenthood, each of which includes different feelings and behaviors. [24] [25] The development of attachment relationships is a transactional process. Specific attachment behavior begins with predictable, apparently innate, behavior in infancy. It varies with age using methods that are partly determined by experience and partly by situational factors. [26] Attachment behavior changes with age, it happens in the process of forming relationships. Child behavior when reunited with a significant adult is determined not only by how he treated the child earlier, but also by the history of the child’s influence on the significant adult. [27] [28]

The most common and empirically proven method for assessing affection in infants (from 12 months to 20 months) is the “Unknown Situation” procedure, developed by Mary Ainsworth as a result of her careful and in-depth observation of infants and their mothers in Uganda (see below). [29 ] The procedure “Unfamiliar situation” is a study that is not a diagnostic tool, that is, the resulting classification of attachments does not equal “clinical diagnosis”. Despite the fact that the procedure can be used to clarify the clinical diagnosis; The results should not be confused with “reactive disorder of childhood attachment.” The clinical concept of this disorder has a number of fundamental differences from the theory and research of attachment, based on the method of the “Unfamiliar situation”. The idea that insecure attachment types are similar to this disorder is, in fact, inaccurate, and leads to ambiguity in formal discussions of attachment theory and its development in the scientific literature.This does not at all detract from the contribution of the concept of reactive disorder of childhood attachment, but rather suggests that the clinical and scientific understanding of unsafe attachment and “reactive disorder of childhood attachment” are not synonymous.

«Незнакомая ситуация» — это лабораторная процедура, используемая для оценки паттернов поведения младенческой привязанности к значимому взрослому. На время процедуры мать и ребенка помещают в незнакомую игровую комнату с игрушками, при этом исследователь наблюдает/фиксирует этапы прохождения через одностороннее зеркало. Процедура состоит из восьми последовательных этапов, в которых ребенок испытывает как отделение и воссоединение с матерью, так и присутствие незнакомого человека.[29] Протокол ведется в следующем формате, если конкретным исследователем не введено никаких иных изменений:

Basically, based on the child’s behavior during reunification (although the remaining behavior patterns are also taken into account) in the “Strange Situation” paradigm (Ainsworth et al., 1978; see below), babies can be divided into three “organized” attachment types: reliable (group B ); closed (group A); anxious (group C). There are also subclassifications for each group (see below). The fourth type, called disorganizing (D), can also be assigned to a child in the procedure “Unfamiliar situation”, although first of all the choice regarding the child is made from the first three types. Each of these groups reflects a different kind of attachment between the child and the mother. A child may have a different type of attachment to each of the parents, as well as to any significant adult. Attachment style, therefore, is not so much a part of a child’s thinking,how much characteristic feature of a certain relationship. However, after about five years, children tend to show one steady pattern of attachment in relationships. [30]

The way a child develops after five years is determined by the specific methods of parental education used in the developmental stages of one child. These attachment patterns are directly related to behavioral patterns and can help predict the future personality of the child in the future. [31]

“The strength of the child’s attachment in these circumstances does not indicate the“ strength ”of the bond itself as a whole. Uncertain children will routinely display bright attachment behavior, while most children who feel safe will not be considered a necessity to engage in intense or frequent images of this behavior. ”[32]

In the classic writings of Ainsworth et al. (1978) in the coding of the protocol “Unfamiliar situation”, babies with a safe (reliable) type of affection are designated as children of “group B”; they are further subdivided into subgroups B1, B2, B3 and B4. [29] Although these subgroups relate to different styles of reactions to the arrival and departure of a significant adult, Ainsworth and her colleagues did not give any names, although descriptions of the behavior of these types allowed another researcher (including Ainsworth students) to develop relatively “free” terminology for these subgroups. B1 is called “reliably stable” ', B2 - “reliably closed”, B3 - “reliably balanced” and B4 - “reliably reacting”. In scientific publications, however, the classification of infants (if subgroups are used) is usually simply “B1” or “B2”,but at the same time more theoretically-oriented publications can use the above terminology.

Children with a reliable type of attachment are more drawn to the study of the environment in the case when they have knowledge of safety (that their significant adult will definitely return if necessary). An adult's help reinforces a sense of security, and when the child realizes the benefits of such an interaction, he learns to cope with similar situations in the future. Thus, a reliable type can be considered as the most adaptive style of attachment. According to some psychological researchers, a child has a reliable type of attachment when the parent is available and able to meet the needs of the child in a responsible and appropriate way. In infancy and early childhood, if parents are caring and attentive to their children, these children will be more prone to reliable attachment styles.[33]

Anxiety-resistant type is also called ambivalent affection . [34] A child with this type of affection will standardly investigate a little (in the “Strange situation”), often be wary of strangers, even if the parent is present. When the mother leaves, the child is often very distressed. At the same time, when she returns, the child will be ambivalent. [29] Anxiety-resistant / ambivalent style strategy is the answer to the unpredictable style of care; and manifestations of anger or helplessness towards a significant adult as a reaction to reunification can be considered as a conditional strategy to maintain the readiness of a significant adult by taking control of the interaction in advance. [35] [36]

Subtype C1 is assigned when:

“... stubborn behavior is particularly striking. A mixture of search, and at the same time resistance to contact; however, the interaction is malicious, and a really angry tone can characterize this behavior before the separation process ... ” [29]

Subtype C2 is assigned when:

“Perhaps the most noticeable characteristic of the C2 subtype in infants is their passivity. Their exploratory behavior is limited to the field of view and there is relatively little active excitation in their interaction. However, during reunification, they clearly want intimacy and contact with their mothers, although they tend to use signals instead of manifestation of motor activity; as well as obviously protesting against the lying position, but without a strong opposing tendency ... In general, the child of subtype C2 is clearly not so angry compared to the child C1. ” [29]

A study by McCarthy and Taylor (1999) showed that children with a rude and negative childhood experience are more likely to form an ambivalent type. The study also showed that children with ambivalent affection tended to experience difficulties in maintaining intimate relationships as early as adulthood. [37]

A child with an anxious avoidance type of affection will, accordingly, avoid or ignore a meaningful adult, and will also show little emotion when a significant adult leaves or returns. The child will be little interested in the environment no matter who is in the room. Infants who were classified as anxious-avoidant type (A) were a puzzle in the early 1970s. They do not respond with grief to separation, and either ignore a meaningful adult upon return (subtype A1), or show some tendency to come closer along with other tendencies to ignore or turn away from a significant adult (subtype A2). Ainsworth and Bell suggested that apparently the unruffled behavior of avoidant babies is in fact a disguise of grief. This hypothesiswas subsequently confirmed by studies of the pulse of babies with this type of attachment. [38] [39]

Младенцы имеют тревожно-избегающий тип в том случае, если:

«… имеет место демонстративное избегание матери в моментах воссоединения, которые, вероятно, состоят игнорирования её полностью, хотя могут быть некоторые взгляды и повороты головы в сторону и движения от … Если есть приветствие, когда мать заходит, то это скорее выражается в виде простого взгляда или улыбки … Ребенок или вовсе не подходит к матери после воссоединения, или он имеет тенденцию подходить только после долгих уговоров … Если ребенка подобрали, то он практически никак не поддерживает контакт; как правило, он не обнимается, отводит глаза и даже может извиваться, чтобы слезть.» [29]

Записи Эйнсворт показали, что младенцы избегали значимого взрослого в стрессовых моментах процедуры «Незнакомой ситуации», когда у них был опыт переживания отказа в привязанности. Это происходит в том случае, когда потребности ребенка не учитываются, и он приходит к убеждению, что удовлетворение его нужд не имеет никакого значения для значимого взрослого. Студентка Эйнсворт Мари Мэйн предположила, что избегающее поведение при процедуре «Незнакомой ситуации» следует считать «условной стратегией, которая парадоксально допускает любую возможную близость в условиях материнского неприятия» путем урезания своих потребностей в привязанности.[40] Мэйн предложила, что избегание имеет две функции для младенцев, чей значимый взрослый постоянно игнорирует их потребности. Во-первых, избегающее поведение позволяет младенцу сохранять условную близость со значимым взрослым: достаточно близко, чтобы быть в безопасности, но при этом достаточно далеко, чтобы избежать отвержения. Во-вторых, когнитивные процессы организации избегающего поведения могут помочь отвлечь внимание от нереализованной потребности близости со значимым взрослым — путем избегания ситуации, в которой ребенка переполняют эмоции, и он оказывается не в состоянии сохранить контроль над собой, и достичь даже условной близости.[41]

Сама Эйнсворт была первой, которая обнаружила трудности в сведении всего младенческого поведения к трем типам, полученным в результате исследований в Балтиморе. Эйнсворт и коллеги в некоторых случаях наблюдали «напряженные движения, например, скрючивание плеч, привычка класть руки за шею, напряженно склонять голову, и так далее. У нас было четкое впечатление, что такая напряженность в движениях означала стресс, поскольку такие движения, как правило, появлялись, главным образом, в моментах разделения, и потому что они преддваряли плач. Наша гипотеза заключается в том, что такие движения имеют место, когда ребенок пытается сдержать плач, потому что они, как правило, исчезают, если этот плач все-таки прорывается наружу.»[42] Такие наблюдения также появились в некоторых докторских диссертациях студентов Эйнсворт. Криттенден, например, отметила, что один случай в её докторской был классифицирован как надежный тип привязанности (В) в ее первоначальной интерпретации, потому что поведение девочки было «не было определено ни как избегание, ни как амбивалентность, при этом она явно демонстрировала типичные стрессовые качания головой во время проведения эксперимента. Это повторяющееся поведение, однако, было единственным ключом к выявлению её напряжения».[43]

Based on reports with models of conflicting behaviors contrary to the A, B, and C classifications, Mary Maine, a colleague of Ainsworth, added a fourth type. [44] In the Strange Situation procedure, it is expected that the attachment system will be activated by the departure and return of a meaningful adult. If the behavior of the infant does not seem to the experimenter naturally associated with the stages of achieving at least some intimacy with a meaningful adult, then this type of attachment is considered disorganizing, and indicates the destruction (for example, fear) of the attachment system itself. The behavior of infants in the procedure "Unfamiliar situation" is encoded as disorganizing / disoriented, if it includes obvious manifestations of fear; inconsistent behavior or if there are signs of simultaneously occurring or sequentially diverse movements of the following types: stereotypical, asymmetrical, sharp or “solidifying”, as well as apparent separation. Lyon-Ruth urged, however, that he should be more broadly interpreted, “that 52% of children with a disorganizing type continue to approach a significant adult, strive for comfort and to end their suffering without clear escape patterns or ambivalent patterns.” [45]

Currently, interest in disorganizing attachment among doctors and politicians, as well as scientists, is growing rapidly. [46] Although this type of classification is criticized by some for being too general, including Ainsworth herself. [47] in 1990, Ainsworth was given a green light for type “D”, work with this classification was put into print, although she argued that any additions would be welcome “in the sense that subgroups can be distinguished and differently”, while she experienced that too many different behaviors will be treated as one and the same. [48] Indeed, D-Classification unites children who use impaired security strategies (B) with those who seem hopeless and show little attachment behavior; he also brings together children who flee to hide when they see a meaningful adult, in the same classification as those who show avoidance strategy (A) during the first reunion, as well as ambivalent (C) strategy during the second reunion. Perhaps responding to such concerns, George and Solomon divided between the indicators of disorganizing / disoriented attachment (D) in the “Unfamiliar situation” procedure, defining some forms of behavior as “despair strategies” and others as evidence that the attachment system was destroyed. , fear or anger). [49] In addition, Crittenden argues that certain behavior, classified as disorganizing / disoriented, can be viewed as more “emergency” versions of avoidant and / or ambivalent / sustainable strategies and have the function of maintaining the ability to protect a meaningful adult to some extent. Sruf et al. agreed that “even behavior with a disorganizing type of attachment (synchronous approach-avoidance; freezing, etc.) activates a certain degree of intimacy in the face of a frightening or totally incomprehensible parent.” [50] However, “the conviction that many indicators of“ disorganization ”are aspects of sustainable behavioral patterns does not preclude the acceptance of the very concept of disorganization, especially in cases where the complexity and danger of a threat are beyond the child’s response potential.” [36] For example, “children placed care, especially more than once, often suffer from obsessions. In the “Unknown situation” video recordings, it is clear that this usually happens when an outcast / neglected child approaches a stranger with an obsessive desire for comfort, then loses muscle control and falls to the floor, gripped by fear of the unknown and fear of the potentially dangerous and alien human. "[51]

Maine and Hesse [52] found that the majority of the mothers of these children suffered major losses or other injuries shortly before or after the birth of the baby and reacted to severe depression. [53] In addition, 56% of mothers who lost their parents due to death before they graduated from high school subsequently had children with a disorganizing type of attachment. [52] Subsequent studies have further analyzed these findings, while emphasizing the potential importance of unworked losses. [54] For example, Solomon and George found that unexplored losses to a mother are usually associated with a disorganizing attachment in their own childhood, especially if they were faced with an unresolved trauma before the loss. [55]

The developed methods allow verbalization of the child’s state from his relationship to affection. For example, the “history of the tree”, in which the child is given the beginning of a story that raises questions of affection, and is asked to complete it. For older children, adolescents and adults, semi-structured interviews are used, and the order in which the content is issued may be more significant than the content itself. [56] Unfortunately, however, there is no reliable method for measuring attachment in preschool or early adolescence (approximately 7 to 13 years). [57] Some studies of older children have defined further classifications of affection. Maine and Cassidy noticed that disorganizing behavior in infancy can manifest itself in a child through caring and controlling or punitive behavior in order to control helpless or threateningly unpredictable significant adults. In these cases, the child’s behavior is organized, but the behavior itself is viewed by researchers as a “disorganizing” form (D), since the hierarchy in the family is no longer subject to parental authority. [58]

Patricia MacKinsey Crittenden has developed a classification for new forms of avoidant and ambivalent attachment behavior. These include care and punitive behavior, also highlighted by Maine and Cassidy (A3 and C3, respectively), as well as other patterns, such as compulsive agreement with the wishes of the threatening parent (A4 format). [59]

Crittenden’s ideas developed from Bowlby’s suggestion that “under certain adverse circumstances stretching from childhood, the selective exclusion of information may be adaptive. However, when the situation changes during adolescence and adulthood, the permanent isolation of certain forms of information may become inadequate. ”[60]

Crittenden suggested that the main components of the human hazard experience are two types of information: [61]

1. "Affective Information" - emotions triggered by a charge of danger, such as anger or fear. In childhood, this information will include emotions provoked by the inexplicable lack of affection figure. Wherever a child faces an insensitive or rejecting parent, the only strategy for maintaining the accessibility of the figure of their attachment is to try to exclude from the consciousness or behavior any emotional information that may entail rejection.

2. Causal or other consistently ordered knowledge of safety potential or hazard. In childhood, this includes behavioral knowledge that indicates the ability of an attachment figure to become a safe haven. If knowledge of behaviors that indicate the attachment figure’s ability to be a safe haven is segregated, then the child may try to hold the attention of a significant adult with tenacious or aggressive behavior, or by alternating both ways. This behavior may increase the accessibility of the attachment figure, which would otherwise look inconsistent or misleading the child, making it unreliable for protection and security. [62]

Crittenden suggests that both types of information can be separated from consciousness or behavioral expression as a “strategy” of maintaining attachment accessibility (see above the section on disorganizing / disorientated attachment for distinguishing “types”): “Type A strategies, according to the hypothesis, should be based on reducing the sense of threat to also reduce the response. Strategies of type C should presumably be based on enhancing the perception of a threat in order to enhance the same response. ”[63] Type A strategy cuts off emotional information about the sense of threat, and type C cuts temporarily-ordered knowledge of how and why the attachment figure is available. In contrast, type B strategies effectively use both kinds of information without much distortion. [64] For example: a baby may become addicted to hysterical strategies of type C in order to maintain the presence of the attachment figure, whose non-permanent presence has led the child to distrust or distort the causal relationship of their own behavior. This can lead a meaningful adult to a clearer view of their needs and to adequately respond to their attachment behavior. By gaining experience with more reliable and predictable information about the presence of a meaningful adult, the child will no longer need to use violent methods in order to maintain the availability of their meaningful adult, and they will be able to develop a reliable type of attachment to it; since children will believe that their needs will be heard.

A study based on data from a longitudinal study of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, a study of early childhood and the Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood, and cross-sectional research, shows the relationship between early attachment types and peer relationships, both in quantitative and and qualitative scale. Lyon-Ruth, for example, found out that “for each additional conclusion of behavior demonstrated by mothers regarding the attachment signals of their child in the“ Unfamiliar situation ”procedure, the probability of contacting clinical specialists increased by 50%.” [65] In addition, there is extensive studies that demonstrate a significant correlation between the structure of attachment and the activities of children in different areas. [66] Early insecure attachment does not necessarily guarantee difficulties, but if such parental behavior continues throughout childhood, this will entail consequences. [67] Compared to children with a reliable type of attachment, the inflexibility of unprotected children in many areas of life may put their future relationships at risk. Although researchers have not yet fully established this connection, there are other factors besides attachment; for example, children with a reliable type are more likely to become socially competent than their insecure peers. Relationships that have developed with other children influence the acquisition of social skills, intellectual development, and the formation of social identity. A peer status classification (popular, unnoticed, or outcast) was created to plan a subsequent correction. [56] Unprotected children, that is, avoiding type, are especially at risk in the family. Their social and behavioral problems improve or worsen depending on their upbringing. Early, reliable attachment has a long lasting protective effect. [68] As in the case of attachment to the parent figure, subsequent experience can change the course of development. [56] Studies have shown that infants with a high risk of autism spectrum disorders may express strong attachment differently than infants with a low risk of this disorder. [69] Behavioral problems and social competence in children with an unreliable type increase or weaken depending on the quality of upbringing and the degree of risk in the family environment. [68] Some authors question the idea that the taxonomy of categories is crucial for the development of attachment relationships. Examination of data from 1,139 children of 15 months of age showed that variations in attachment patterns were continuous, rather than grouped. [70] This criticism raises important questions for the attachment typology and the mechanisms behind particular types. However, it has relatively little meaning for attachment theory itself, which “not only does not require, but does not predict different attachment patterns.” [71] There is some evidence that gender differences in attachment value patterns of adaptive values begin to manifest themselves in preschool age. Unreliable attachment and early psychosocial stress indicate environmental risks (for example, poverty, mental illness, instability, minority status, violence). Environmental risk can lead to unreliable attachment, as well as contributing to early reproduction strategies. Different reproductive strategies have different adaptive meanings for men and women: men tend to adopt a avoidant strategy, whereas unreliable women tend to adopt disturbing / ambivalent strategies if they are at very high risk of average risk. Adrenarch suggests that endocrine mechanisms underlie the reorganization of precarious attachment at preschool age. [72]

Childhood and adolescence allow the internal working model to become useful for the formation of attachment. This internal working model relates to an individual personal state, which, based on childhood and adolescent experiences, develops in relation to attachment as a whole and explores the role that attachment plays in the dynamics of relationships. The essence of the internal working model is that those children who develop it have more stable attachments than those who rely only on their condition.

The age, level of cognitive development and constantly received social experience develop and complicate the internal working model. Behavior, attachment loses some of the properties characteristic of the preschool period, and begins to transform according to age trends. The pre-school period involves the use of bargaining and bargaining. [73] For example, four-year-old children are not upset by separation if close people have already agreed with them on a common plan for separation and reunion. [74]

Peer influence becomes more important in the preschool years, and this influence is different from the parent.

Ideally, these social skills are embedded in an internal working model that will be used to interact with other children, and later with adult peers. When children go to school (about six years old), most of them develop a special form of cooperation with parents, in which each partner is willing to compromise to maintain harmonious relations. [73] Upon reaching school age, the goal of the attachment behavioral system changes from the proximity of the attachment figure to its presence. In general, the child is satisfied with greater autonomy, provided that the contact — or the possibility of physical presence, if necessary — is present. Attachment behavior, such as clinging and stalking, is reduced, and the child’s independence increases. By school age (from 7 to 11), there may be a shift towards mutual regulation of interaction, in which a significant adult and child agree on methods of maintaining communication and control as the child moves to a greater degree of independence. [73]

Attachment theory was extended to adult romantic relationships in the late 1980s by scientists Cindy Hazan and Philip Shaver. In adults, four styles of attachment were identified: reliable, anxious, preoccupied, scornful, and closed-phobic. These styles roughly correspond to the classification in children: reliable, alarmingly ambivalent, avoiding and disorganized / disoriented.

Adults with a reliable type of attachment, as a rule, have a positive opinion about themselves, their partners and their relationships. They feel comfortable in intimacy and independence, easily balancing between them. Anxious-avoiding adults tend to have a high level of closeness, acceptance and responsiveness of partners, becoming overly dependent. They are usually mistrustful, have less positive opinions about themselves and their partners, and can show a high level of emotional expressiveness, anxiety and impulsiveness in relationships. Neglect-closed adults, want a high level of independence, which is often manifested in the avoidance of attachment in general. They consider themselves self-sufficient, invulnerable to sensual affection; and do not need a close relationship.They tend to suppress their feelings, struggling with the rejection of retreating partners, about which they often have a bad opinion. Closed-phobic adults have mixed feelings about intimacy, at the same time wanting and feeling discomfort from emotional intimacy. They, as a rule, do not trust their partners and believe that they themselves do not cost anything. Like the neglected-closed adults, the closed-phobic adults avoid intimacy by suppressing their feelings. [75] [76] [77] [78]

Romance attachment styles in adults roughly correspond to infant attachment styles, but adults can draw a line between different internal working patterns for different relationships.

Two major aspects of adult attachment were studied. Social psychologists who are interested in romantic attachment have studied the organization and sustainability of the thinking model that underlies attachment styles. [79] [80] Developmental psychologists are interested in individual thinking about attachment, and they usually investigate the role attached attachment in the dynamics of relationships, and how it affects their outcome. The organization of thinking patterns is more stable, while the thinking of individuals regarding attachment fluctuates more. Some authors have suggested that adults do not have a single set of working models. However, in fact, at a certain level, they have a set of rules and assumptions about the relationship of affection in general.At another level, they contain information about specific relationships or significant events. Information at different levels should not be consistent. People, therefore, can use different internal working models for different relationships. [80] [81]

There are many ways to measure adult attachment, the most common of which is an independent questionnaire and coded interview based on the “Adult Attachment Interview”. Various measures have been developed primarily as research tools for different purposes and interpersonal fields, such as romantic relationships, parental relationships, or peer relations. Some classify adult thinking about attachment and its patterns of reference to childhood experiences, while others evaluate the relationship between behavior and security feelings regarding parents and peers. [82]

На Боулби повлияли ранние идеи психоаналитической школы объектных отношений, в частности идеи Мелани Кляйн. Однако, он был глубоко не согласен с распространенным психоаналитическим убеждением, что ответные реакции младенцев относятся к их фантазийной внутренней жизни, а не к реальным событиям. В то время как Боулби формулировал свою собственную концепцию, он находился под влиянием случаев нарушенного и делинквентного поведения детей, например, таких, о которых Уильям Гольдфарб писал в 1943 и 1945 годах.[83][84]

Время молитвы в приюте Дома Пяти Углов, 1888. Гипотеза материнской депривации была опубликована в 1951 году и вызвала в детских приютах настоящий переворот.

Современник Боулби Рене Спитц наблюдал горе разлученных детей, предполагая, что эти «психотоксические» результаты были достигнуты из-за неадекватных переживаний в раннем уходе.[85][86] Также сильное влияние оказала работа социального работника и психоаналитика Джеймса Робертсона, который снимал последствия разделения детей в больнице. Вместе с Боулби они сотрудничали при создании документального фильма 1952 года « Двухлетний ребенок попадает в больницу », который сыграл важную роль в кампании по снятию ограничений на посещение родителей в больницах .[87]

В его монографии 1951 года для Всемирной организации здравоохранения, Материнская забота и психическое здоровье , Боулби выдвинул гипотезу, что «младенец и маленький ребенок должен испытывать теплые, близкие, и непрерывные отношения с матерью, в котором оба находят удовлетворение и удовольствие», и недостаток которого может иметь серьезные и необратимые последствия для психического здоровья. Данная работа была также опубликована в изданиях « У ход за ребенком» и « Развитие любви» и стала общественным достоянием. Теория была очень влиятельной, однако одновременно весьма спорной.[88] В то время не было достаточного количества эмпирических данных и исчерпывающей теории для того чтобы серьезно учитывать такие результаты.[89] Тем не менее теория Боулби вызвала яркий интерес к природе ранних отношений и дала сильный импульс, (по словам Мэри Эйнсворт), «большой объем исследований» в чрезвычайно трудной, сложной области.[88] Работы Боулби (и фильмы Робертсона) вызвали настоящую революцию в разных сферах больницы: в правилах посещения родителей, в обеспечении игровых потребностей детей, их образовательных и социальных нужд, а также в работе приютов. Со временем детские дома были заброшены в пользу приемных семьей в большинстве развитых стран.[90]

After the publication of Maternal Care and Mental Health , Bowlby looked for new explanations in the fields of evolutionary biology, ethology, developmental psychology, cognitive science, and control systems theory. He formulated the ground-breaking claim that the mechanisms underlying the emotional connection of a child with a significant adult appeared as a result of evolutionary pressure. He set out to develop a theory of motivational and behavioral control, based on a scientific approach, and not on the Freudian model of mental energy. Bowlby argued that a lack of information and theory did not prevent him from grasping the causal link in his work “ Maternal care and mental health .

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 Attachment Theory in Children and Adolescents

Часть 2 Biological basis of attachment - Attachment Theory in Children and

Comments

To leave a comment

Interpersonal relationships

Terms: Interpersonal relationships