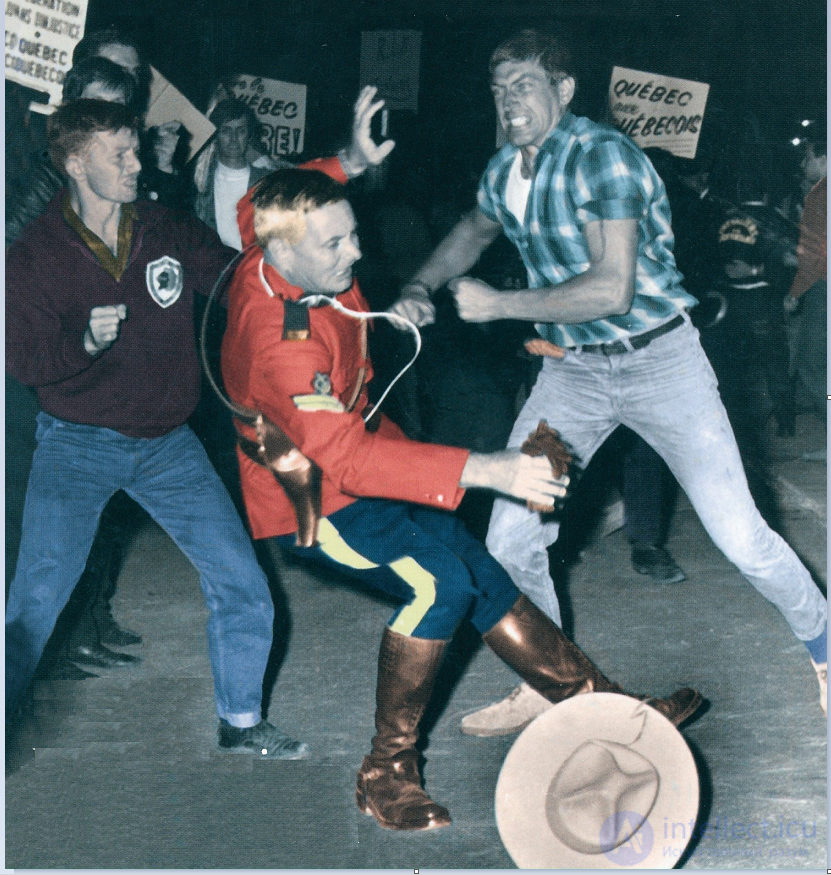

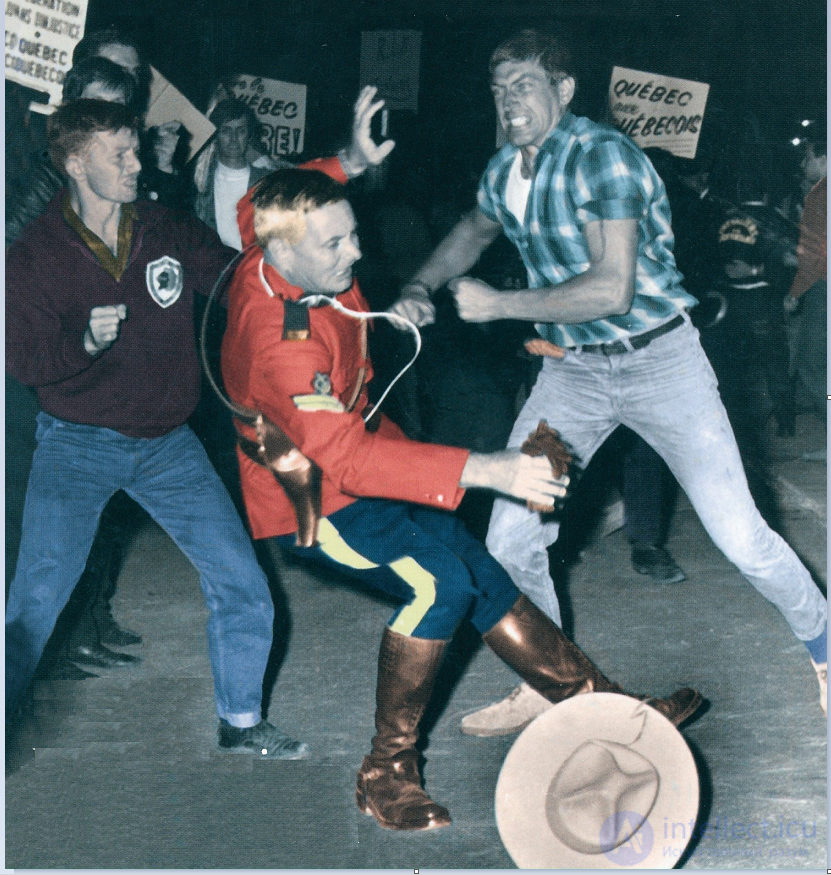

The face of a man who is ready to be attacked and brutal is angry. A separatist demonstrator on the right just hit a Canadian policeman, and a demonstrator on the left is going to do it. However, we do not know what happened up to this point. Did a policeman attack a demonstrator? Did the demonstrator act within the framework of the necessary self-defense or was his violence not provoked by any means? Is attack response a topic of anger, a universal trigger that triggers the emotion of anger?

Emotional scholars have proposed many different themes for anger, but so far there is no evidence that one of them is the main one; in fact, for this emotion there may be combined themes.

The most effective way to provoke anger in children - sometimes it is used by scientists-psychologists to study this emotion - is physical intervention by holding the child’s hands in such a way that he cannot use them freely.

[101] This is a metaphor for one of the most common causes of anger for children and adults: creating obstacles to what they intend to do. If we think that the intervention was intentional, and not accidental or forced, if the person who is hindering us intentionally decided to interfere with us, then our anger can become even stronger. Frustration with anything, even an inanimate object, can also cause anger.

[102] We may be disappointed even by weakening our memory or some other physical or mental ability.

When someone tries to cause us physical harm, then the likely reaction to such a threat will be anger and fear. If someone tries to cause us moral harm, insulting us, mocking our appearance or denigrating our activity, it is also likely to cause anger and fear. As noted in the previous section, a person rejected by his beloved has not only sadness, but also anger. Some spouses or lovers who are enraged because they are abandoned are beaten by those who leave them. Anger controls, punishing anger, revenge anger.

One of the most dangerous features of anger is that it generates anger itself, and this cyclical process can evolve incrementally. You must have an angelic character to calmly respond to the manifestations of the anger of another person, especially when his anger seems unjustified and arrogant. Thus, the wrath of another person may itself be considered as another cause of anger.

Frustration with the way a person acted can also cause our anger, especially if we are deeply attached to this person. It may seem strange that we can be angry most of all about those whom we love the most, but it is these people who are capable of causing us the greatest emotional distress. In the early stages of a romantic relationship, we can indulge ourselves with various pleasant fantasies about the subject of our adoration and experience anger when it does not correspond to our invented ideal.

[103] It may also seem safer for us to be angry with a loved one rather than a stranger. Another reason why we can be angry most of all about those we sincerely care about is that these people know us well, know our fears and weaknesses and everything that can hurt us the most painful of all.

We can be angry with a person, even a complete stranger to us, if he tries to justify the actions and beliefs that offend us. We do not even need to meet with this person, as we can experience deep anger, simply by reading that someone carries out actions or promotes ideas with which we fundamentally disagree.

Proponents of the evolutionary theory of Michael McGuayr and Alfonso Troisi

[104] put forward a very interesting assumption that people usually exhibit different “behavioral strategies” in response to different causes, themes and variations of anger. Indeed, there is reason to believe that different causes of anger will not cause anger of one type or one intensity. When someone rejects or disappoints us, we can try to harm him, although an attempt to harm the robber can cost us our lives.

Some may argue that the frustration, anger of another person, the threat of damage and the loss of a lover are variations of the same topic of intervention. Even anger at the one who defends the wrong, from our point of view, actions and ideas, can also be seen as a variation of the same theme. But I believe that it is important for people to consider these factors as different triggers and determine for themselves which one is the most powerful, the hottest trigger of anger. The word “anger” encompasses a number of related emotional states. There are several varieties of this emotion: from mild irritation to rage. They differ not only in the strength of the feeling experienced, but also in the type of anger experienced. Resentment is self-righteous anger; gloom is passive anger; bitterness comes when patience comes to an end. Vengeance is a type of anger-induced action, usually starting after a period of thinking about the insult received; sometimes these actions are more cruel than the act that provoked them.

If anger is brief, then it can manifest itself in the form of resentment, but prolonged discontent is another thing. If a person enters, in your opinion, unfairly, you can not forgive him for this and harbor a grudge against him for a long time, sometimes for a lifetime. This does not mean that you will constantly experience anger, but whenever you see this person or think about him, anger will boil in your chest. Grievance can become like an unhealed wound and regularly remind of itself. An offended person can constantly reflect on the insult inflicted on him. Usually in such cases, the probability of revenge is greatly increased.

Hate is a long-lasting and lasting dislike. We do not experience constant anger at someone we hate, but meeting with this person or even hearing a message about him can easily arouse our angry feelings. We are also very likely to have disgust and contempt for the person we hate. Like a feeling of insult, hatred is also usually long-lasting and aimed at a specific person, but it is more general in nature, while the feeling of resentment causes individual actions. Hatred can also glow in a person for years, forcing him to often think about who insulted him.

It is difficult to understand how to classify hatred and long-term resentment. They cannot be attributed to emotions, as they last too long. They are not attitudes for the same reason, and also because we know why a person causes our hatred and resentment, while the reason for our mood usually remains unknown to us. I even thought about calling resentment an

emotional attitude , and hating an

emotional attachment along with romantic and parental love. Thus, I wanted to emphasize that these feelings contain signs of anger, but are not anger as such.

Earlier, I argued that the message conveyed by the expression of sadness is a plea for help. It is much more difficult to identify the only message for anger emotion. The words “out of my way” seem to partially express the essence of this message, i.e. contain a threat to the source of interference. However, such a message does not seem to be suitable for anger caused by the anger of another person or anger experienced in relation to a person, which can be read in the newspaper that he has committed some outrageous acts. And sometimes anger is a feeling caused by the desire not only to remove the person who is insulting from his path, but also to harm him. Anger is rarely experienced for long. Often, fear precedes anger first and then comes to replace it: the fear of the potential harm that an object of anger can cause, or the fear of one's own anger, the fear of losing control over oneself, the fear of harming other people. Some people experience a mixture of disgust and anger when they are repulsed by the person they are trying to attack. Or disgust can be directed at himself for showing anger, for the inability to control his emotions. Some people feel guilty or ashamed of their anger.

Anger is also the most dangerous emotion, because, as was shown in the photo of actively protesting demonstrators, angry people may try to harm the object of their discontent. Anger can only be expressed in words, but the motive will remain the same - to harm the one who caused this anger. But is this impulse to harm an obligatory and integral element of the anger reaction pattern? If this is so, then we should see attempts at causing harm at an early age and observe their weakening only when the child begins to learn to suppress this impulse. If this is not the case, then the impulse of anger could simply be directed to the problem without necessarily trying to harm the person who caused the anger. But in this case, we would observe angry behavior that harms only those children who would learn from their educators or other people that harming a person is the most effective way to overcome the problem. It is important which answer to the original question is correct. If harming is not an integral element of the anger reaction pattern, then it is possible to raise children in such a way that the desire for harm is not part of their behavior in an angry state.

I asked two leading experts

[105] on the expression of anger in infants and young children about the presence of irrefutable evidence in support of one or another point of view, and they said that there was no such evidence. Joe Campos, the ancestor of the study of emotions in children, spoke about the "power actions that seem to perform the function of removing obstacles" in newborns, and referred to the so-called "proto-anger" that occurs in infants in various situations involving interference with their actions - for example, removal from the breast during feeding. However, it is unclear whether these movements are targeted attempts to harm the person who is the source of interference, or simply attempts to remove the obstacle. There is also no precise information about when and how attempts to cause harm occur and whether they occur in all babies.

There is evidence that attempts at striking and causing damage in a different way are observed at a very early age in most children, but they begin to be controlled from about two years of age and then become weaker from year to year.

[106] Psychiatrist and anthropologist Melvin Conner recently wrote: “Ability to violence ... never disappears ... It always exists."

[107] These words are quite consistent with my observations of my own children, who very early began to make attempts to harm other people. They needed to be taught to suppress this reaction and develop other ways of dealing with interference, attacks and other external influences. I suspect that in almost all of us the impulse to harm is central to the reaction of anger. However, I am also confident that we all differ noticeably in the strength of these impulses.

Although we can condemn people for what they say and do in a state of anger, we understand their behavior. It will be incomprehensible for us to behave like a person who harms other people without anger, or a person who often looks really scared. People often regret the words spoken in a fit of anger. Apologizing, they explain that they acted under the influence of anger, that the words they uttered should not be taken seriously and that their real attitudes and beliefs were distorted under the influence of this emotion. This condition is perfectly illustrated by the phrase "I completely lost my head." Apologies are not easy as long as there are any signs of anger, and they are not always able to repair the damage.

If we are

attentive to our emotional state, that is, if we are not just aware of how we feel, but we can also take a pause to consider whether we want our actions to be guided by the anger we are experiencing, we will still have to endure the struggle. if we decide not to act under the influence of this emotion. For some, this struggle will be harder than for others, because for some of us, anger can arise faster and manifest itself with greater intensity. Sometimes we really want to act on the basis of our anger, and, as I will explain later, actions performed in a state of anger can be useful and necessary.

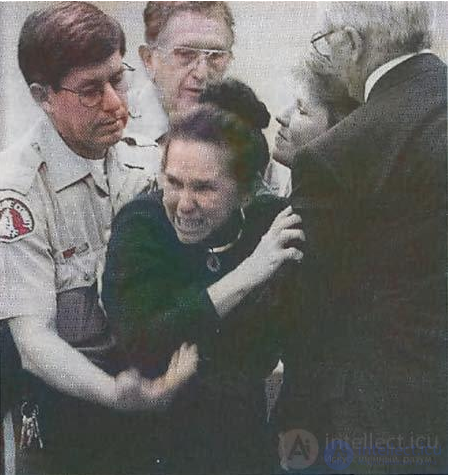

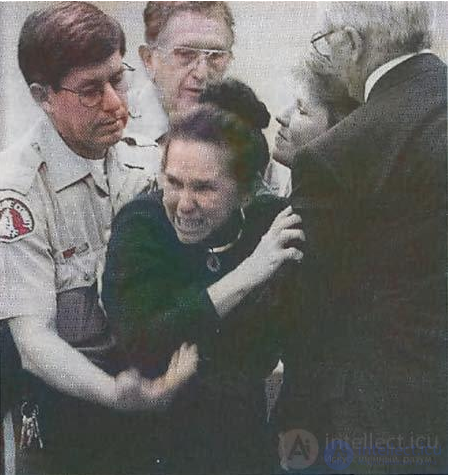

David Lin Scott, a twenty-six year old man who declared himself a ninja, raped and killed Maxine Kenny’s daughter in 1992. Scott was arrested in 1993, but the trial lasted for four years. After Scott was convicted, Maxine and her husband Don were given the opportunity to speak during the final phase of the process. Maxine turned to Scott directly, saying, “Do you think you're a ninja? Come to your senses! This country is not feudal Japan, and even if it were her, you would never have become a ninja because you are a coward! You wandered around at night, dressed in all black, carrying weapons with you and hunting innocent, defenseless women. You raped and killed them because it gave you a false sense of your own power. But you look more like a dirty disgusting cockroach that runs along the walls at night and infects all around. I have no sympathy for you. You raped and brutally murdered my daughter Gale by stabbing her seven times with a knife. You did not spare her when she was desperately fighting for life, as evidenced by the numerous wounds in her arms. You do not deserve to be left alive. ” Scott, who had no remorse, smiled while Mrs. Kenny spoke. Returning to her seat, she managed to hit Scott on the head before her husband and the police managed to grab her hands (this moment is shown in the photo).

Often the fact that motivates us to control anger and not allow it to grow into a rage, is our commitment to maintaining relationships with the person to whom we direct our anger. No matter who this person is - our friend, employer, employee, spouse or child, and no matter what he did, we believe that we can irrevocably destroy our future relationship with him if we are unable to control our anger. But Maxine Kenny had no relationship with Scott before and did not expect any future relationship that could motivate her not to act under the influence of this emotion.

Of course, we can treat Maxine's anger with understanding and sympathy. Any of us in her place might well have experienced the same feeling. Although we may not approve of her attacks on Scott, it is still difficult for us to condemn her actions. Perhaps Maxine reached her limit of strength when she saw that her daughter’s killer did not express regret and remorse and only smiled coldly at her accusations. Would everyone act the same way in her place? Does this behavior indicate the achievement of tensile strength? Is there a tensile strength for each of us? I do not think so. Maxine's husband, Don, did not act under the impulse to commit violence; on the contrary, he kept his wife from attacking Scott.

Maxine and Don Kenny experienced the most terrible event for any parent: the brutal murder of their child, committed by a stranger without any intelligible reason. Eight years after their thirty-eight-year-old daughter Gail was raped and murdered, they told me that they still suffer and are acutely aware of her absence. Why did Maxine and Don behave differently that day in the courtroom?

Perhaps, Maxine has a “short fuse” and quickly comes to an angry state, although she herself claims that this is not typical for her. Her husband Don comes to an angry state slowly, as he restrains his emotions, which grow gradually. People with a high rate of growth of anger find themselves in a more difficult situation than everyone else when they want to hold back their anger reactions and prevent the anger from growing into a rage. Although Maxine does not believe that she has a “short fuse,” she claims that she could have exploded if she “thought that my family was threatening something.”

Maxine told me: “I always experience emotions in a very strong form ... I think that people experience emotions with different strengths. There are people with a different emotional temperament, and some of them are more emotionally excitable. ” I told Kenny's spouses that I was doing research on the topic Maxine touched on, and I think that she is right (this work is described at the end of section 1 and in conclusion).

We all differ in how intensely we experience each of our emotions. Some people may simply be incapable of strong anger and never show frantic rage. Different expressions of anger arise depending not only on the duration of the fuse, but also on how quick-tempered a person is, and the degree of hot temper cannot be the same for everyone. Scientists are not yet aware of the source of such differences and the ratio of the roles of the genetic factor and the external environment. In any case, each of these factors plays a role.

[108] Later, I will talk about the results of a survey of people known for their unusually strong anger.

Maxine informed me that she did not know in advance that she was going to hit David Scott. She thought she could insult him verbally and limit it to that. But the flow of verbal abuse is able to open “floodgates” to anger and allow it to quickly increase, making it difficult for a person to “turn on the brakes” and restrain himself from physical attack. During a break in court hearings, Maxine explained to the reporter her attack on David Scott: “It was like a temporary insanity. I just could not hold it in myself anymore. ” When asked if she thinks now, looking back that she was insane at the time, Maxine said: “Yes, I remember a feeling of strong hatred ... The anger was so strong that I didn’t even think about the consequences.” (Perhaps somewhat unexpectedly for all, Don later reproached himself for not attacking David Scott either.

[109] )

I am sure that almost everyone is able to prevent actions and statements from being in a state of anger or even in a state of rage. Note that I said “almost”, as there are people who are apparently unable to control their anger. This may be a congenital feature of the character or the result of damage to some area of the brain. Such an explanation is not suitable for Maxine, since she was always able to control her emotions.

Although we may be urged to utter insulting words or to cause physical harm, most of us are able to force ourselves not to do this. A few words can come out of the mouth, and the hand can make an indefinite movement in the air, but the general control is available to almost everyone. All of us, or practically all, can make a choice in favor of rejecting violence, refusing to cause harm by words or actions. Maxine made a conscious choice in favor of speaking in the final phase of the trial and decided to speak as sharply as she could. She is proud of the hatred that she still has.

I expect most people to resort to violent acts if such actions prevent the killing of their child, but can this be considered a true loss of control? When violence provides a worthy goal, few condemn it. It may not be impulsive, but carefully planned. Even His Holiness the Dalai Lama believes that violence in such circumstances is justified.

[110]

I understand that not everyone, even in such extreme circumstances, would act cruelly. It is unlikely that those who would not act in this way would have such a high threshold of anger that only more serious provocations could make them lose control of themselves, since it is difficult to imagine an even more provocative provocation. In my research, during which I asked people to describe situations that could cause the most intense anger, the threat of death to a family member was often called. But I am sure that even when only violent actions can prevent the death of a family member, not everyone will act in this way. Someone may not do this out of fear, and some because of the conviction that violence is unacceptable.

Maxine Kenny's attack on David Scott is a different matter. It could not prevent a murder; it was an act of vengeance. We understand her actions, but most of us would not act in this way. Every day, many parents have to see the murderers of their children in the courtrooms, but most of these parents do not try to commit acts of retribution. However, it is difficult not to sympathize with Maxine Kenny, not to feel that she did something right, because the crime was terrible, and her loss was irreplaceable. But despite this, the man who raped and murdered her beloved daughter calmly sat in the courtroom and smiled at the words of the suffering mother. Can one of us say with confidence that, being in her place, he would not have done the same?

Before meeting with Maxine and Don Kenny, I argued that hatred is always destructive, but now I’m not so convinced about it. Should we expect that we will not feel hatred and the desire to hurt the person who raped our child, who stabbed him with seven deadly stabs? Could Maxine’s incessant hatred of David Scott not serve a useful purpose if, figuratively speaking, she bandaged the wounds of a suffering mother? Maxine’s hatred did not provoke "festering" in her soul; Maxine was directing her life in a positive direction, but at the same time retaining hatred for David Scott.

Most of the time, we do not even respond to serious provocations, when we just experience irritation. However, anger, sometimes even very strong, can arise when the provoking event seems to others to be quite insignificant. This may be a manifestation of disagreement, challenge, insult, weak frustration. Sometimes we may prefer not to control our anger, not to care about the consequences, or for a moment just not to think about them.

Psychologist Carol Tabris,

[111] who has written a whole book about anger, argues that manifesting your anger — as other psychologists call for — usually makes the situation worse. After carefully analyzing the research results, she concluded that repressed anger “does not cause depression, does not cause ulcers or hypertension, does not induce us to overeat, and does not cause a heart attack ... It is unlikely that repressed anger has medical consequences if we control the situation that caused it, if we interpret anger as a sign of the existence of a reason for dissatisfaction, which should be corrected, and not as an emotion that must be gloomily maintained, and if we feel our obligations ed in our work and living with us humans. "

[112]

There are costs of manifesting our anger.

[113] Angry actions and angry words can destroy friendships, quickly and often permanently, and create hostile relations instead. But even without angry actions and angry words, our angry face expression and angry voice of our voice will signal our condition to the one to whom our anger is directed. If this person responds with irritation or contempt, then it may be more difficult for us to maintain control over the situation and avoid a skirmish. After all, angry people very few people seem to be pretty. Studies have shown that angry children lose the disposition of other children,

[114] and angry adults are considered socially unattractive individuals.

[115]

I am sure that we usually find ourselves in a better position when we do not act under the influence of our anger or when we make sure that our actions are constructive, that is, they do not involve an attack on a person to whom we are angry. The angry person should consider, although he often does not do this, whether the fact that caused his anger is really the best way to respond is a manifestation of anger. Although sometimes this is indeed the case, there are many other situations that can be corrected more easily if you turn to the source of discontent after the anger is suppressed. However, there are moments in which we do not pay attention to the fact that we further worsen the situation, do not care about future relations with the object of our anger.

With strong anger, at first we may not know or even not want to know that we are in an angry state. I am not talking here about our inability to be

attentive to our emotional feelings . The point is not that we can not step back and think about whether we want to continue to act under the influence of our anger. Rather, we simply do not know that we are angry, even though we utter angry words and carry out angry actions.

It is not at all clear how or why this is happening. Maybe we do not know about our anger, because knowing about him is like condemning ourselves? Can some angry people be more likely to be unaware of their anger than others? Would such ignorance be more characteristic of anger than of other emotions? Is there a level of anger, the achievement of which always means that an angry person must know about his anger, or does it also depend on the characteristics of each individual? When is it harder to become

attentive to our emotional feelings: when do we experience anger, fear or grief? Unfortunately, scientific research, allowing to give answers to these questions, has not yet been conducted.

The main benefit of being aware of feelings of anger and of being

attentive to them is the ability to regulate or suppress our reactions, re-evaluate situations and plan actions most likely to eliminate the source of our anger. If we do not know what we are feeling and just act under the influence of our emotions, we cannot achieve any of the above results. Unaware of our feelings, unable, even for a moment, to think about what we are going to do or say, we are more likely to do things that we later regret. Even if we know about our anger, but we cannot be

attentive to him, we cannot step aside and think for a while about what is happening, we cannot decide for ourselves what we will do.

Usually our ignorance of the anger being experienced does not last long. Those who see and hear the manifestations of our anger can tell us about them, and we ourselves can also hear the sound of our voice or imagine it, based on what we think and plan. Such knowledge does not yet guarantee the establishment of control, but makes it possible. It will be useful for one to follow the old adage, advising to count to ten before doing something, and it will be better for others to leave the game at least for a short time in order to suppress their anger.

There is a special way to respond to anger, causing problems in relationships between loved ones. My colleague John Gottman discovered the so-called “shelter behind a stone wall” phenomenon in the course of his research on happy and unhappy marriages.

[116] This phenomenon, more often seen in men than in women, is evasion of interactions and an unwillingness to respond to the emotions of a spouse. Usually “shelter behind a stone wall” is a reaction to the anger or complaints of the wife; it provides the husband with a safe haven because he feels incapable of dealing with his feelings and the feelings of his spouse. But the relationship of the spouses would suffer less if, instead, the husband agreed to listen to his wife’s complaints, realized her anger and offered to discuss the problem later, when he could prepare for the conversation and be able to control himself better.

Richard Lazarus, an emotional theory writer, described a very difficult method of managing anger, difficult because his goal was not just to control anger, but also to weaken it: “If your wife or lover insulted you in word or deed, then instead of trying to heal your injured self-esteem with acts of retaliation, you could realize that being in a state of severe stress, she cannot be responsible for her actions, that, in fact, she does not control herself and that it would be best to recognize that in based on her intentions not lying to you ill. Such a reassessment of the other person’s intentions makes it possible to show sympathy for his condition and excuse the outburst of his anger. ”

[117] However, Lazarus acknowledges that this is easier said than done.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama

[118] described the same approach, demanding to see the differences between the actions that offend us and the person who committed these actions. We try to understand why a person behaved aggressively, and we try to evoke sympathy for him, paying special attention to what could have caused him to feel anger. This does not mean that we do not inform a person that his actions have caused us suffering. But our anger is directed not at this man, but at his actions. If we can accept this scheme, we will not want to hurt him; we just want to help him not to behave this way in the future. But there are people who do not want to receive such assistance. For example, a bully and bully can tend to dominate others, and a cruel person can enjoy suffering others. Only anger directed directly at himself, and not at his actions, is able to rationalize such a person.

What is offered, each in its own way, Lazarus and the Dalai Lama, may be feasible when the other person does not act maliciously. But even when we are not dealing with malicious anger, our own emotional state influences how we can show our reaction. It is easier to be angry at the action, and not at the person committing this action, when our anger is weak, when it grows slowly, and we are fully aware of our emotional state. Managing our actions is especially difficult in a period of immunity, when information that does not fit in with our anger becomes inaccessible to us. This way of dealing with anger will not always be possible, but after a certain practice it can be applied quite successfully, at least for a while.

At the working meeting held a few months ago, I observed just such constructive anger. Our group of five people was engaged in planning a research project.John opposed our plan, telling us that we were naive, that we were trying to invent a wheel, and that, in fact, we were bad scientists. Ralph objected to him, noting everything that we really took into account, and our discussion continued. John began again to interrupt us, repeating, even more sharply, what he had said earlier, as if he had not heard Ralph’s answer. We tried to continue the discussion without answering him directly, but he did not let us do that. Then Ralph took the floor and told John that we understood him, that we did not agree with him and that we could not allow him to continue to interrupt our work. He said that John could stay if he would sit in silence or give us all possible assistance, otherwise it is better for him to leave the room. I listened carefully to the voice of Ralph and watched his face. I saw and heard signs of hardness,strength and determination, perhaps even a faint display of impatience, a slight trace of anger. There was no attack on John, no mention of his hectic behavior, which actually took place. John, who had not been directly attacked by Ralph, did not defend himself and in a few minutes left the room, and, as was evident from his subsequent behavior, without any offense. Later, Ralph, answering my question, said that he was experiencing moderate anger. He also said that he had not planned this speech at all, and that it simply turned out the way it turned out. It should be noted that Ralph specializes in teaching children how to cope with their anger.Ralph, who was not directly attacked, did not defend himself and left the room a few minutes later, and, as was evident from his subsequent behavior, without any offense. Later, Ralph, answering my question, said that he was experiencing moderate anger. He also said that he had not planned this speech at all, and that it simply turned out the way it turned out. It should be noted that Ralph specializes in teaching children how to cope with their anger.Ralph, who was not directly attacked, did not defend himself and left the room a few minutes later, and, as was evident from his subsequent behavior, without any offense. Later, Ralph, answering my question, said that he was experiencing moderate anger. He also said that he had not planned this speech at all, and that it simply turned out the way it turned out. It should be noted that Ralph specializes in teaching children how to cope with their anger.that Ralph specializes in teaching children how to deal with his anger.that Ralph specializes in teaching children how to deal with his anger.

Everyone has difficulty controlling anger when in an irritated mood. When we are annoyed, we become angry at something that would not cause our irritation if we were at rest. We ourselves are looking for opportunities to show our anger. When we are annoyed, then that which could only cause a slight discontent in us causes us to feel anger, and that which could cause us to experience moderate anger makes us angry. Anger that occurs on the background of irritated mood lasts longer and is more difficult to control. No one knows how to get out of an irritated state; sometimes indulgence in pleasurable actions may help, but not always. I advise you to avoid people when you are annoyed and aware of this.Often an irritated mood remains unclear until the first outbreak of anger, and then you realize that it happened because you are annoyed.

Given the attention that is being paid to managing anger in this section, it may seem like anger is a harmful or non-adaptive emotion. Or that the anger was adaptive for our ancestors engaged in hunting and gathering, but is not adaptive for us. But such conclusions do not take into account several very useful functions of anger. Anger itself can motivate us to eliminate or change what caused us to experience it. Anger at injustice motivates us to make changes.

It is useless to simply absorb the anger of another person or not respond to it at all. The person attacking you should be made to understand that his actions are unpleasant to you if you want him to stop them. Let me explain this with another example. Imagine that Matthew and his brother Martin have different talents and abilities and each of them is not too happy with their work. The brothers meet Sam, who has many acquaintances in the business world and could help them find a better job. Matthew plays a dominant role in the conversation, interrupting Martin and not letting him express his opinions. Martin gets angry and starts to show his anger. He exclaims: “Listen, all the time you only talk about Sam with your affairs; finally give me a chance to speak out! ”If he says this with anger in his voice and face,It may not make a very good impression on Sam. Although in this way he can stop Matthew, he will have to pay a certain price for it, since using the vulgar word “idle” is a kind of insult. Matthew, in retaliation, can let go of his own impish remark, and as a result both brothers will lose Sam’s help.

If Martin realized his anger before opening his mouth, if he realized that, although Matthew acts unfairly, his motivation is not directed against his brother, then he could act differently. He could have told Sam: “You have already heard a lot about Martin’s affairs, but I want to be sure that I will be able to describe my situation before you leave.” Later, he could have told Matthew that he understood how important this meeting was to him, but he became afraid that Matthew had spent the whole time talking to Sam, forgetting that he, Martin, also had questions to Sam. If Martin could say it in a casual manner, with a bit of humor, it would increase the likelihood that Matthew will understand his words correctly. If inattention and injustice towards others are not characteristic features of Matthew, then Martin is probablywouldn't talk about them. If these traits are truly present in Matthew’s character, then Martin might have wanted to emphasize how unfair his brother was. If Martin says this with anger, then Matthew can be impressed by the seriousness of his words, but perhaps such anger will provoke anger in return and no progress can be made.

The message that we should receive from our own anger contains the question: “What makes me feel anger?” The reason is not always obvious, and sometimes it turns out to be different from what we think. Surely, many people, being in a state of frustration, “reward with a kick of an innocent dog”, i.e. pour out my anger on someone who did not insult us at all. Such a shift of anger can occur when there is no opportunity to openly direct it to the person who has annoyed us and instead we choose as a victim to whom we can be angry with absolutely safely.

Anger tells us to change something. If we want to make this change most efficiently, we need to know the source of our anger. What was it: an obstacle to what we were going to do, a threat of harm, an insult to our human dignity, a sharp refusal, the anger of another person or a wrong action? Was our perception of what happened adequate or were we in an irritated mood? Can we really do something to weaken or eliminate the reason for discontent, and will the expression of our anger or the action under the influence of anger help to eliminate the cause of this emotion?

Although anger and fear often arise in the same situations, in response to the same threats, anger can help reduce fear and generate energy to take action to eliminate the threat. Anger is often seen as an alternative to depression, because it allows you to blame others instead of yourself for the trouble, but it cannot be said with certainty that this is so, since anger can also arise in a state of depression.

[119]

Anger informs others about the trouble. Like all emotions, anger has its own signal - a powerful signal that manifests itself both in the face and in the voice. If the source of our anger is another person, then our expression of anger will tell this person that any of his actions are considered unpleasant. It may be useful for us to let others know. With rare exceptions, nature has not provided all of us with a special button that allows us to turn off any of our emotions in situations where we do not want to have them. Just as some people can enjoy sadness, others can enjoy their anger.

[120]They are looking for opportunities to get involved in a conflict; the exchange of expressions of hostility and offensive words pleasantly excites them and brings them satisfaction. Some people enjoy even the usual fights. Close relationships can establish or recover from an intense exchange of angry statements. Some couples claim that after a quarrel or even fights, their sexual relationship gives them particular pleasure. But there are also people for whom the experience of anger turns out to be very harmful, and therefore they do everything possible to never experience this emotion. Just as each emotion corresponds to its saturated mood, there are also character traits in which each emotion plays a central role. For anger, such a trait of character is hostility.My studies of hostility were aimed at identifying signs of hostility and its health effects.

During the first study

[121]I, together with my colleagues, tried to find out whether a facial expression has a special sign that makes it possible to classify a person as type A or type B. This difference, nowadays no longer causing the same interest as during this study fifteen years ago was supposed to help identify those people whose aggressiveness, hostility and impatience made them most susceptible to coronary artery disease (type A). People of type B, by contrast, are more balanced. Recent studies have shown that it is hostility that is the most important risk factor for a disease. Hostile people should probably be more angry, and this was the assumption we were going to test in our study.

We studied the facial expressions of middle-level managers of one large company, and these people were already classified by experts as belonging to type A or type B. All of them underwent moderately provocative interviewing, during which the researcher cast the surveyed managers into a state of easy frustration. Our technicians used the method that I developed with my colleague Wally Frisen to measure facial movements, the Facial Coding System (

FACS ). As explained earlier, this method does not measure the power of emotions directly; instead, it objectively takes into account all movements of the facial muscles.

FACS technical

assessors, did not know what type each person belongs to. They used slow-motion and re-viewing of video to determine the movements of the muscles of the face. Analyzing the results, we found that the special expression of anger - called by our

fierce eyes(this partial expression of anger is characterized by lowered eyebrows and raised lower eyelids - see picture below) - more often appeared in people of type A than in people of type B. It was a ferocious look, rather than an expression of anger all over the face, perhaps because that people of type A tried to ease any signs of their anger. These people were experienced leaders: they knew that they should have tried to prevent the appearance of anger on their face. Another possibility was that they were simply annoyed, and since their anger was mild, it did not manifest itself on the whole face.

Ferocious look

The main drawback of this study - the lack of knowledge of what happened to the cardiovascular system of these people when a fierce look appeared - was eliminated in our next study. My former student, Erika Rosenberg, studied with me patients who have already been diagnosed with a serious coronary artery disease. These people were exposed to what is called ischemic episodes, during which the heart for some time did not receive enough oxygen. When this happens, most people experience pain, which signals them to stop any movement, because otherwise they may have a heart attack. The patients we studied had a mild form of ischemia, did not experience pain, and received no warning signals that their heart was not receiving enough oxygen.

In the course of this study,

[122] conducted jointly with a group of scientists led by James Blumenthal of Duke University, the interviewed patients were also videotaped. This time, the constant measurement of the ischemic state was carried out with the help of a device mounted on the patient's chest; This device showed an image of the patient's heart at the time when the person spoke. We measured facial expressions at two-minute intervals, during which patients answered questions about how they deal with anger in their daily lives.

Those who were in the ischemic state expressed anger in certain areas of the face or on the whole face more often than those who did not experience this condition. The appearance of anger on his face during the story of recent disappointments suggested that these people did not just talk about anger, but relive it. And anger, as we know from other studies, leads to an increase in heart rate and increased blood pressure. This is like a quick climb up the stairs. You should not do this if you suffer from coronary artery disease, but not everyone follows this recommendation. Those who did not come into a state of anger were less likely to be in the ischemic state.

Before explaining why, as we think, we obtained these results, let me clearly state the following: this study did not show that it is anger that causes heart disease. In another study

[123], it was found that either hostility as a personality trait, or the emotion of anger (but it is unclear in what form) is

oneof the risk factors for heart disease - but in our study we did not seek to obtain such a result. We just found that in people already suffering from heart disease, anger attack increases the risk of an ischemic condition, in which the likelihood of a heart attack also increases. Now let's look at why these people were angry when they talked about their anger in the past, and why it threatened their health.

All of us from time to time have to talk about emotions that we are not experiencing at the moment. We share our memories of a sad event, of those moments when we experienced anger, of what caused us fear, etc. Sometimes, when describing our past emotional experience, we begin to experience emotion again. This, I believe, was precisely what happened to people who were in ischemic condition. They could not talk about the experience of anger without experiencing anger again. Unfortunately, for people with coronary heart disease, it is very dangerous. But why does this happen to some people and not to others? Why do some re-experience the past experience of anger, while others do not? Apparently, anger is easy to provoke; it easily arises at the first suitable situation for those in whom a hostile attitude towards people is developed.When the recollection of the anger that caused the anger again makes one experience the previously experienced feelings, this is both a sign and a manifestation of the presence of hostility in the person.

But besides people whose hostility is a character trait, any of us may also find that he is reliving past emotional experiences while thinking about the events that have caused this experience. I suspect that this usually happens when an event does not get completed. Consider the case when the wife is angry with her husband because he was late for dinner again, without warning her about his delay. If the conflict ended without bringing her satisfaction (her husband did not apologize, did not explain why he could not call her, or did not promise never to do it again), then she will probably begin to experience this anger again later. Thinking that she raises this topic again because now she is able to talk about what happened calmly, the wife can again feel the anger boiling in her. Similar can happeneven if this conflict can be resolved, but the wife will remember a series of other unresolved events that also caused her indignation, with the result that she will have a supply of unsatisfied anger waiting to break out.

I am not going to say that it is impossible to describe the past experience of anger without experiencing anger again. It is quite possible if there is no stock of accumulated anger and if the conflict has been successfully resolved. In addition, it is quite permissible, when talking about a past emotional event, to use part of the expression of anger to illustrate what you felt then. For example, I could tell my wife how tired and angry I was when I tried to settle my problems with the Tax Administration of the USA all day and heard only general information from the answering machine on all the numbers I knew. Suppose that then I threw my anger at the employee, to whom I finally got through, and received apologies that satisfied me. Now I could show an element of anger on my face - what I call

reference expression.

[124] The reference expression refers to an emotion that is not currently being tested; its analogy can be the “pronouncement” of the word “anger” not with a voice, but with a face. The expression really needs to be transformed in some way, so that the person who sees it does not become confused and would not think that anger is being experienced now. Typically, this result is achieved by expressing anger only a part of the face, and within a short time.

The reference expression of anger can be created using only the raised upper eyelids, or only compressed lips, or just lowered eyebrows. If you use more than one of these elements, it can confuse the person who sees this expression, and make you feel anger again. After all, by giving the face the expressions described in the previous chapter, you found that if your face muscles perform all the movements typical of a given emotion, then usually you yourself begin to experience this emotion.

продолжение следует...

Comments

To leave a comment

Psychology of emotions

Terms: Psychology of emotions