Surprise - this is the shortest of all emotions, lasting no more than a few seconds. A surprise instantly passes as soon as we become aware of what is happening, and then turns into fear, joy, relief, anger, disgust, etc., depending on what surprised us, or after surprise there can be no emotion if we determine that the event that surprised us had no consequences for us. Photos of people expressing surprise are quite rare. Since surprise happens unexpectedly and is experienced very quickly, the photographer is rarely ready to take pictures, and if it does, it does not always work fast enough to capture the right expression when something amazing happens. Photographs in the press usually show a specially portrayed surprise.

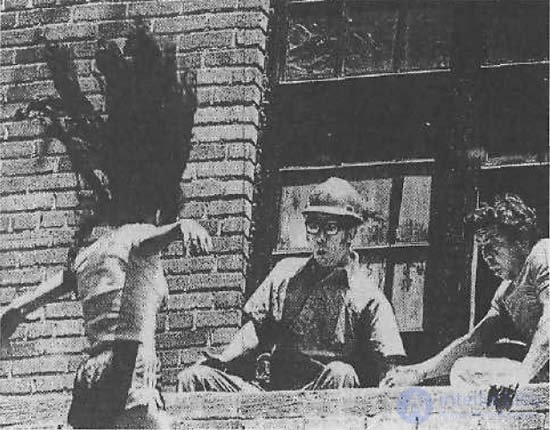

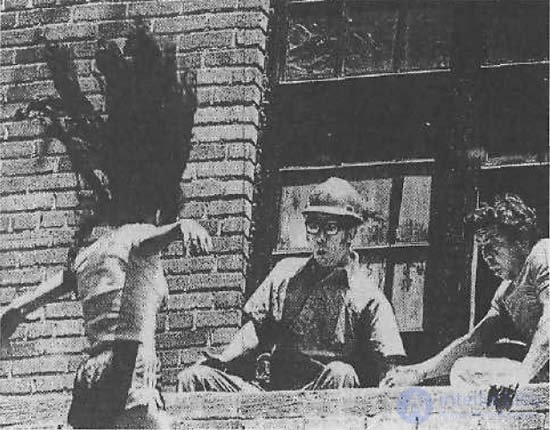

The photo correspondent of the New York Post newspaper Lou Liotta talked about what allowed him to make this award-winning photograph of two surprised men:

“I got a call and was invited to drive up to this house, next to which the woman showed her spectacular publicity stunt. I arrived late when she, holding onto the end of the rope with her teeth, was already raised to the level of the roof of the building. I put a long-focus lens on the camera and was able to see the intense look in her eyes. Her body rotated around a vertical axis. Then her teeth opened. I followed her fall and took one shot. ”

Fortunately, the woman shown in this picture did not die, although when she fell onto wooden flooring from a height of thirty-five feet she broke her wrists and ankles and injured her spine. However, for us the main interest is the emotions of two men caught in the camera lens. Surprise can only be caused by a sudden, unexpected event, as was the case here. When an unexpected event unfolds slowly, we are not surprised. The event should happen suddenly, and we should not be ready for it. Men who saw the fall of a woman performing a publicity stunt did not receive any warning signal and had no idea what should happen next.

Several years ago, when I first taught medical students how to understand and recognize emotions, I tried to evoke different emotions in each practical lesson. To surprise them, I invited a belly dancer and asked her to unexpectedly step out from behind the screen in her exotic outfit. Her appearance would have been natural in some nightclub, but in the classroom of the medical faculty of the university she looked unusual, and her unexpected and noisy exit caused everyone to be surprised.

We have little time to consciously mobilize to control our behavior when we are surprised. This rarely creates problems for us, unless we are in a situation in which we should not look surprised. For example, if we declare that we are perfectly versed in a certain issue, and we are surprised when a detail suddenly turns out, which we had to know about, then it will be obvious to others that we do not own this question so well. In the audience, a student can say that she has read the recommended book, although in reality she did not have time to do it. Her surprise, appearing at the moment when the teacher talks about some unknown places in this book, can give her away.

Some scholars who study emotions do not consider surprise to be emotion, because it is neither pleasant nor unpleasant, and, in their opinion, any emotion must possess one of these two qualities. I disagree with them. I believe that surprise is

felt as an emotion by most people. A few moments before we understand what is happening, before we switch to another emotion or stop experiencing any emotions, surprise itself can be perceived as pleasant or unpleasant. Some people never want to be surprised, even about a pleasant event. They ask others to never surprise them. Other people, on the contrary, love to be surprised; they intentionally do not plan many things in their lives in order to perceive them as unexpected. They seek to gain experience, which with a high probability will allow them to experience surprise.

My own doubts about whether a surprise is an emotion arise from the fact that its distribution in time is fixed.

[134] Surprise can not last more than a few seconds, which distinguishes it from other emotions. They can be very brief, but can also last much longer. Fear, which often replaces surprise, can be very short-lived, but it can also persist for a long time. When I had to wait a few days for the results of the biopsy to find out if I was sick with cancer, and if so, at what stage the disease is, I experienced long periods of fear. I did not experience fear continuously for all four days of waiting, but these days there were occasional situations when I experienced fear for many seconds or even minutes. Fortunately, the result of the biopsy was negative. After that, I felt relieved and experienced joyful emotions.

I think it makes sense to include surprise in the list of emotions we are considering, noting that it has its own specific characteristic - a limited duration. Each of the previously reviewed emotions also has its own unique characteristics. The emotion of sadness / grief is unique in at least two ways. First, it can manifest itself in the form of submissive sadness, in the form of active grief, and secondly, it can persist longer than other emotions. Anger is different from other emotions in that it is most dangerous to others because of the threat of violence. And as we will see later, contempt, disgust, and many types of pleasure also have their own special characteristics not inherent in other emotions. In this sense, each emotion has its own story.

Surprise is still an emotion, but emotion cannot be considered a fright. Surprise and fright look different: the expression of fright is completely opposite to the expression of surprise. In order to cause a fright to the unsuspecting objects of my research,

[135] I unexpectedly fired blank cartridges with a pistol. Almost immediately, their eyes closed (with surprise, they open), eyebrows lowered (with surprise, they rise), and their lips became tensely stretched (with surprise, the lower jaw drops).

In all other expressions of emotions, the limiting expressions resemble moderate expressions. Rage is an extreme form of anger, horror is an extreme form of fear, etc. The difference between frightened and surprised expressions implies that fright is not just a stronger form of surprise.

Fright is different from surprise in three aspects. First, the time of manifestation of fright is even more limited than the time of manifestation of surprise - the expression of fright appears after a quarter of a second and disappears in half a second. It is so fleeting that if you blink your eyes you will not notice the expression of fright on your vis-a-vis. In any emotion, the time of its manifestation is not so limited. Secondly, warning a person that he will be frightened by a very loud noise reduces the reaction force, but does not eliminate the reaction at all. But you cannot be surprised if you know what is going to happen. Thirdly, no one can suppress the reaction of fear, even if he knows exactly when a loud noise will arise. Most people can suppress in themselves all but the weakest signs of emotion, especially if they are prepared for this in advance. Fright is more a physical reflex than an emotion.

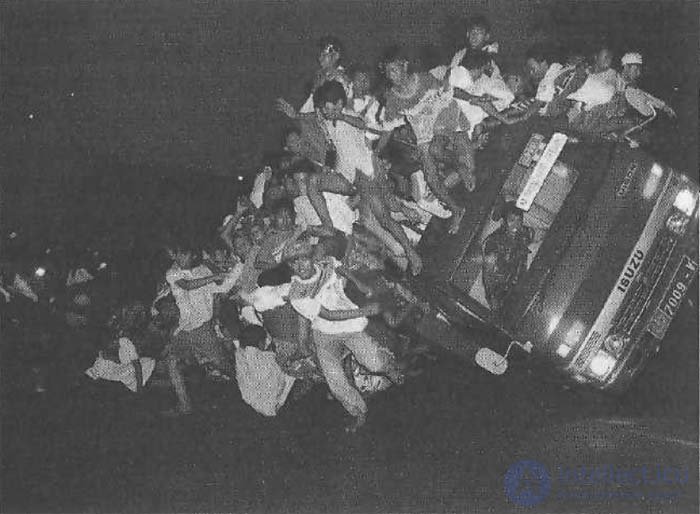

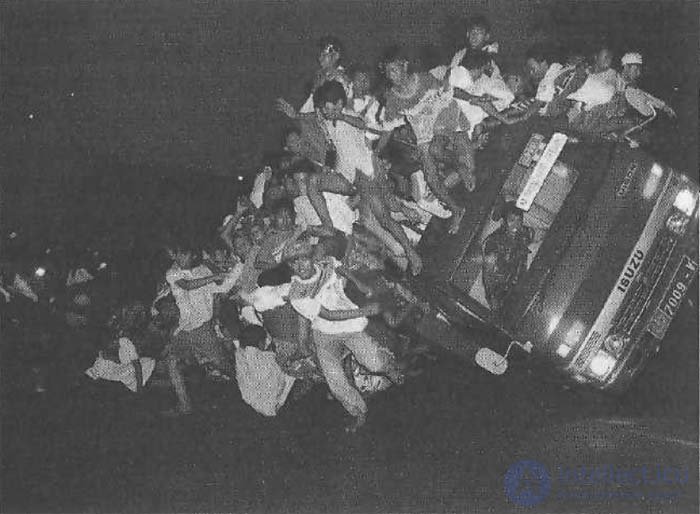

The caption under this amazing photo reads: “In Surabaya, East Java, a military truck unexpectedly overturned, carrying more than a hundred young people. The truck passengers were fans of the local football team, who enjoyed the opportunity to get home free and waved flags in honor of the victory of their favorite team. The truck, one of twenty-four provided by the local military command, rolled over, having driven only one kilometer. Most of the passengers were not injured, but the two had to be hospitalized with minor injuries. ” Fear is read on the faces of these young people, but it is most clearly visible on the face of the driver. If the picture had been taken a moment earlier, then we might see a surprise on our faces — until the truck began to roll over slowly.

More research has been devoted to the study of fear than any other emotion, perhaps because fear can be easily aroused in almost all animals, including rats (which have become favorite objects of research because of their fertility and low maintenance costs). The threat of harm, physical or moral, is characteristic of all triggers of fear, as well as the themes of fear and their variations. The theme is the danger of causing physical harm, and variation can be anything that, as we know, can harm us in any way, that is, either physical or moral threat. Just as a physical limitation is a congenital trigger for anger, there are also similar triggers for fear: for example, Something that moves quickly in space and can strike us if we don’t bounce to the side, or a sudden loss of support that causes our fall. The threat of physical pain is a congenital trigger for fear, although fear may not be felt directly at the moment of pain.

Snake species can be another innate, universal trigger. Recall Ohman's research, described in section 1; these studies have shown that we are biologically prepared to be more afraid of the appearance of reptiles than the appearance of guns or knives. However, a significant number of people show no fear at the sight of snakes; on the contrary, they enjoy physical contact with them, even very toxic ones. I am tempted to assume that being in a high place, where any wrong step can cause a fall, is another inherent trigger. I have always been horrified by such situations, but this is not a trigger for fear for a significant number of people.

Perhaps each of us has non-innate incentives of fear. There is no doubt that some people are afraid of things that pose virtually no danger, and behave like children who are afraid of the dark. Adults, like children, may have groundless fears. For example, attaching electrodes to the chest in order to remove the ECG may alarm people who do not know that the electrocardiograph only detects heart activity and does not produce any electrical signals. People who think that they will receive a blow experience a real, albeit groundless fear. It is necessary to have a well-developed ability for sympathy in order to show respect, compassion and patience to someone who is afraid of something that we are not afraid of. Instead, most of us brush off such fears. We do not need to feel the fear of another person in order to recognize it and to help another person cope with this fear. Good nurses understand their patients; they are able to stand on their point of view in order to calm and comfort them.

When we feel fear, we can do almost everything or not do anything, depending on the knowledge we have gained about what can protect us in the situation we are in. Animal studies and the results we obtained in studying how people physiologically prepare to commit actions suggest that in the process of evolution, two very different actions were preferred: trying to hide from danger and trying to escape. When fear arises, blood rushes to the big muscles of our legs, preparing us to escape.

[136] This does not mean that we will necessarily run, but only that evolution has prepared us to perform an action that has turned out to be the most adaptive throughout the past history of the human race.

Many animals, faced with a danger, for example in the form of a predator, first freeze to reduce the likelihood of their detection. I watched this reaction when I approached a group of monkeys that were in a large cage. Most monkeys froze when I came closer so as not to be noticed. When I was getting even closer, so that the direction of my gaze clearly indicated which monkey I was looking at, this animal took flight.

If we do not freeze and do not run, then the next likely reaction will be anger at what threatens us.

[137] Quite often, it is anger that quickly replaces fear. There is no confirmed scientific evidence that we can experience two emotions at the same time, but from a practical point of view, this is not so important. We can alternately experience fear and anger (or any other emotion) so quickly that these feelings will merge. If the person threatening us looks stronger, then we will probably feel fear, not anger, but we may also occasionally or after eliminating the danger of feeling anger at the person who threatened us with harm. We may also be angry with ourselves for being scared if we believe that we should not have been afraid in this situation. For the same reason, we may be disgusted with ourselves.

Sometimes we are powerless to do anything when faced with the inevitability of causing serious damage - like the driver of an overturned truck. Unlike people in the back of a truck who could focus their attention on how to jump to the ground, he could not do anything, although the danger to his life was high. However, something very interesting happens when we are able to cope with an immediate serious threat, similar to that which has arisen for people in the back of a truck. Unpleasant thoughts and feelings characteristic of fear may not be experienced by us, but instead our minds can concentrate on solving the current problem, that is, on how to cope with the threat that has arisen.

For example, when I first arrived in New Guinea in 1967, I had to hire a single-engine plane to fly to the village, from which I could walk to the village I needed. Although by that time I already had to fly a lot in different countries of the world, I was rather afraid of the upcoming flight and even began to sleep poorly at night. I was worried about the need to fly on a single-engine plane, but I had no other choice, since there were no roads in that part of the island where I was going. When we took to the air, an eighteen-year-old curly pilot, next to whom I was sitting in our two-seater plane, shared with me the news that, as the aerodrome ground service workers told him on the radio, the landing gear broke down on our plane. He announced that we should go back and try to sit on the plowed field next to the runway. Since the plane could catch fire on landing, the pilot ordered me to prepare for an emergency landing. He advised me to slightly open the door, so that in case of a serious deformation on impact, I could still get out. He also warned me not to open the door too wide so as not to fall out of the plane when we are in the air. Needless to say, our seats were not equipped with seat belts.

While we were circling over the airfield, preparing for landing, I did not experience any unpleasant sensations and did not have disturbing thoughts about possible death. On the contrary, I was thinking about how funny everything turned out: I flew to the island for more than two days, and when I got to the destination hour of the flight, I had to turn back. A few minutes before the emergency landing, everything seemed funny to me, not scary. I saw a fire brigade lined up along the runway to welcome our return. When we touched the ground, I slightly opened the cabin door, as the pilot taught me. Then everything became quiet. We were able to avoid fire, injury and death. For fifteen minutes we loaded my luggage from a damaged plane into a serviceable one, and then took off again. Suddenly I felt anxiety because this scene could repeat and that this time its finale might not be so happy.

After this forced landing, I interviewed other people who, being in an extremely dangerous situation, did not experience any unpleasant sensations and did not have disturbing thoughts.What distinguishes them and my experience from those situations in which fear was actually being tested is the ability to do something in order to cope with the danger. If there was an opportunity to do something for salvation, then fear was not felt. If it was impossible to do anything and it remained only to hope for a miracle, then people often experienced horror. If I did not focus on the need to slightly open the cabin door and prepare to jump out of the plane, then probably during our landing I would feel a strong fear. We are most likely to have an overwhelming fear when we can do nothing to save ourselves, and not when we are focused on countering an immediate threat.

Recent studies have revealed three types of differences in emerging fear, depending on whether the threat is immediate or only approaching.

[138] First, different threats cause different behaviors: an immediate threat usually triggers an action (freezing in the same posture or flight), allowing you to somehow deal with the threat, while concern about the approaching threat leads to increased vigilance and muscle tension. Secondly, the reaction to an immediate threat often relieves pain, while anxiety caused by the approaching threat intensifies the pain. Finally, thirdly, there are data from studies indicating that the immediate threat and the approaching threat are associated with the activation of different areas of the brain.

[139]

Panic is a stark contrast to a person’s response to an immediate threat. Work on this section was interrupted by the need to go to hospital and undergo surgery to remove part of the intestine. I did not feel fear until the announcement of the date of the operation. Then, for five days before the operation, I experienced several bouts of panic. I felt a strong fear, began to breathe intermittently, a chill struck me, and I could not think of anything but an event that frightened me. As I mentioned in section 5, thirty years ago I had a serious operation and, because of a medical error, I had to endure severe pain, so I had every reason to fear the consequences of falling on the operating table. These panic attacks lasted from ten minutes to several hours. However that daywhen I arrived at the hospital for surgery, I did not experience panic or fear, since now I could do something to counteract them.

According to three factors:

- intensity - how can you harm?

- time - is it harmless or approaching?

- To prevent a threat?

Unfortunately, not a single study considered all these three factors at once, which made it difficult to identify the type of fear that was being studied. Photos of expressions of fear appearing in the press give us some clues and often allow us to recognize the intensity of the threat, immediate or approaching, as well as assess the possibilities to cope with it. Looking at the photo of the truck, we can assume that the driver is terrified: the danger is great, but he cannot cope with it, because he is locked in the cab. The expression on the driver's face corresponds to one of those expressions that I have identified as universal for fear. Some of the passengers who are trying to do something, in particular, jumping to the ground or about to jump, do not demonstrate this expression, but have a more attentive, focused look, which, I believe, characterizes the readiness to cope with an immediate threat. Photographs of people awaiting a threatening event show an expression similar to that of the driver’s horror, although less intense.

When we feel fear of any type, when we realize that we are frightened by something, it is difficult for us for a certain time to experience some other feeling or to think about something else. Our mind and our attention are focused on the threat. When an immediate threat arises, we focus on it until we seek to eliminate it, or if we find that we cannot do anything about it, then we begin to experience horror. Waiting for the threat of harm may completely capture our consciousness for a long period of time, or such feelings may be episodic, returning to us from time to time and interfering in our thinking, when we do other things, as it was with me in those days when I expected the results of the biopsy. Panic attacks are always episodic, if they continued, not weakening, all day, then a panicked man would inevitably die from physical and nervous exhaustion.

The immediate threat of harm focuses our attention, mobilizing us to overcome the danger. If we perceive the threat as approaching, then our concern for what may happen is able to protect us, warning us of the danger and making us more vigilant. Our facial expressions, when we are worried about the imminent possibility of harming us or when we are terrified, if the threat is very serious, signals others to avoid this threat or call on them to come to our aid. If we look worried or frightened when someone attacks us or is only going to attack, then this may force the attacker to retreat, being satisfied with the realization that we will not continue the actions that provoked his attack. (Of course, this is not always the case. An attacker who is looking for a weak victim can interpret the expression of fear as our unwillingness to fight and the inability to protect ourselves.) The presence of signs of panic in our fear should motivate others to give us help and moral support.

The basis of fear is the possibility of causing us pain, physical or mental, but pain itself is not considered by psychologists as an emotion. Why, may someone ask, is pain not an emotion? It really can be a very strong sensation on which all our attention is concentrated. The answer to this question, given by Silvan Tomkins forty years ago, still looks convincing. He argued that pain was too concrete to be an emotion. Due to the existence of different types of pain, we can know exactly where it hurts. But where are anger, fear, anxiety, horror or sorrow and grief located in our body? As in the case of erotic feelings, when we experience pain (if it is not an irradiating pain), we unmistakably know what is bothering us. If we hurt a finger, we will not rub our elbow to relieve pain, and even less we doubt which part of the body we want to stimulate when we experience sexual arousal. Both pain and sexual attraction are very important and cause us a lot of emotions, although they themselves are not emotions.

Earlier, I noted that some people like to be surprised. Each of the so-called negative emotions can be positive in the sense that some people, experiencing it, can have fun. (That is why, unlike many scientists studying emotions, I consider it wrong to divide emotions into positive and negative.)

Some people seem to really enjoy the fear they are experiencing. Scary novels and horror films are very popular. I often sat in the cinema with my back to the screen, watching the faces of the audience, and saw expressions of anxiety and even fear along with an expression of pleasure. In the course of our research, we showed the subjects, who were alone in the room, scenes from horror films and filmed their facial expressions with a hidden camera. We found that those who had a frightened face also showed changes in the physiological parameters of the body - an increased heart rate and blood flow to the large muscles of the legs, which are characteristic of people experiencing fear.

[140]

Some may argue that these viewers are not in danger and know that they will not be harmed. But some people are not limited to observing the vicissitudes of someone else’s life, they seek immediate thrill and enjoy the deadly risk they put themselves in while practicing extreme sports. I do not know what gives them pleasure: experienced fear, arousal caused by a sense of danger, or relief and pride, experienced later, after reaching the goal.

There are also people of quite the opposite type, for whom the sensations of fear are so heavy that they make extraordinary efforts not to experience them. There are groups of people who, while experiencing a particular emotion, receive pleasure, and there are their antipodes who cannot bear it at all, and besides them there are many people who do not seek to experience this emotion, but also do not perceive it harmful for themselves in most situations.

Each of the emotions we have examined plays a role in creating an appropriate mood that can persist for many hours. When we feel sad for a long time, we are in a sad mood. When we easily break out in anger and look for a reason to show sharp discontent, we are in an irritated mood. I use the term “anxiety” in relation to a mood in which we feel concern and don’t know what causes it — that is, we cannot indicate the corresponding trigger. Although we feel as if we are in danger, we do not know what to do, as we cannot identify the threat.

Just as sad mood, melancholic personality type and depression are related to sadness / grief, and irritable mood, aggressive nature and pathological propensity to violence - to anger, fear is associated with anxious mood, timid or shy personality types and many disorders that I will describe below. For example, studies show that extreme shyness is characteristic of 15% of the population.

[141] Such people are concerned about the possibility of their inadequate behavior in a specific social situation, they avoid human contact, have low self-esteem, high levels of stress hormones and high heart rate. They are also more at risk for heart disease.

[142] Renowned researcher Jerome Kagan believes that parents usually distinguish between three personal characteristics associated with fear: they call children, shunned, shy; children, avoiding unfamiliar situations, timid; and children avoiding taking an unfamiliar looking, discerning.

[143] Many researchers distinguish between two, rather than three types of shyness: the usual shyness in which a person fluctuates, whether or not he should avoid strangers and new situations, and shyness caused by fear, in which a person simply avoids strangers and new situations .

[144]

There are many emotional disorders in which fear plays a major role.

[145] Phobias are among the most obvious and perhaps the most famous: they are characterized by a fear of abstract events or situations, a fear of death, a fear of injury, illness, bloodshed, a fear of animals, the opportunity to be in a crowded closed room, and . p. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (

PTSD ) is considered to be the result of getting into an extremely dangerous situation, after which a person begins to regularly re-experience the traumatic event and avoid others. events associated with the injury. Repeated panic attacks are another emotional disorder associated with a state of anxiety and intense fear. Often they cover a person for no apparent reason and can lead to a loss of self-control.

Pathological anxiety is another emotional disorder that differs from the usual anxious mood in that it repeats more often, lasts longer and manifests itself in a stronger form, preventing a person from working and sleeping normally.

Comments

To leave a comment

Psychology of emotions

Terms: Psychology of emotions