I have included in this book everything that I have learned about emotions over the past forty years and that, in my opinion, can help a person improve his emotional life. Most of what I have written - but not all - is supported by the results of research by other scientists involved in the study of emotions. The special purpose of my own research was to develop a professional ability to read and measure the expression of emotions on the face. Possessing such a skill, I could discern on the faces of strangers, friends and family members those nuances that most people do not notice, and thanks to that I would learn about them a lot more and in addition would have time to test my ideas through experiments. When what I write is based on my own observations, I emphasize this fact with such words as "according to my observations", "I am sure", "it seems to me ..." And when what I write is based on the results of scientific experiments I give a link to a specific source that supports my words.

Much of what is written in this book came under the influence of the results of my intercultural facial expressions. They forever changed my view on psychology in general and on emotions in particular. These results, obtained in countries as diverse as Papua New Guinea, the United States, Japan, Brazil, Argentina, Indonesia, and the former Soviet Union, helped generate my own ideas about the nature of emotions.

During my first research in the late 1950s, I did not show any interest in facial expressions at all. All my attention was focused on the movements of the hands. My method of classifying gestures made it possible to distinguish between neurotic and psychotic depressed patients and to assess how much their condition improved after treatment.

[1] In the early 1960s. There has not even been a method for directly accurate measurement of complex, often very fast facial movements that depressed patients have demonstrated. I had no idea where to start, and did not take any real action in this direction. A quarter of a century later, when I developed a method for measuring facial movements, I went back to the films on which these patients were shot, and managed to make the important discoveries described in section 5.

I do not think that in 1965 I would transfer the focus of my research to the study of facial expressions and emotions, if not for two favorable events. First, the Agency for Advanced Research Projects (ARMA) under the US Department of Defense provided me with a grant to research non-verbal behavior in different cultures. I did not claim to receive this grant, but as a result of the scandal that broke out, the main research project of APRA (actually serving as a cover to support insurgents in one of the southern countries) was covered and the money allocated for it needed to be spent somewhere abroad for research cause no suspicion. By a happy coincidence, I was at the right time in the office of the person who was supposed to spend the money. He was married to a native of Thailand and was impressed by how her non-verbal communications differed from those that were familiar to him. For this reason, he wanted me to find out that in such communications is universal, and that is characteristic only for specific cultures. At first, this prospect did not please me, but I decided not to retreat and prove my ability to cope with this task.

I started to work on the project in full confidence that facial expressions and gestures are the result of social learning and change from culture to culture, and I also thought those experts to whom I originally asked for advice: Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, Edward Hall, Ray Birdwhistle and Charles Osgood. I remembered that Charles Darwin was of the opposite opinion, but I was so sure that he was wrong that he did not take the trouble to read his book on this issue.

Secondly, my meeting with Silvan Tomkins was a great success. He has just written two books about emotions, in which he asserted that facial expressions are innate and universal for our biological species, but did not have evidence to support his statements. I don’t think that I’d ever read his books or meet with him if we both didn’t simultaneously submit our own articles to the same scientific journal: it’s about facial study, and I’s about body movement research.

[2] I was greatly impressed by the depth and breadth of Silvan’s thinking, but I believed that he, like Darwin, adhered to the erroneous conception of innateness, and therefore the universality of facial expressions. I was glad that another participant entered into the argument and that now not only Darwin, who wrote his work a hundred years ago, opposed Mead, Bateson, Birdwistel and Hall. The case took a new turn. There was a real scientific dispute between famous scientists, and I, who had barely stepped over the thirty-year boundary, had the opportunity, supported by real funding, to try to resolve it once and for all, giving an answer to the following question: are facial expressions universal or, like languages, specific to each specific culture? It was impossible to resist such a prospect! I didn't care who was right, although I didn't think Silvan would be right.

[3] In the course of my first research, I showed photos to people from five countries (cultures) - Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Japan and the USA - and asked them to evaluate what emotions were displayed by each facial expression. Most people in every culture agreed that expressions of emotion can indeed be universal.

[4] Carroll Isard, another psychologist who was consulted by Silvan and who worked in other cultures, conducted almost the same experiment and obtained the same results.

[5] Tomkins did not tell me about Isard, and Isard did not tell me about me. At first, both of us were dissatisfied with the fact that almost the same research was simultaneously carried out by two different scientists, but it was especially valuable for science that two independent researchers came to the same conclusion. Apparently, Darwin was right.

But how could we establish that people from many different cultures agreed on what kind of emotion was shown in the picture, while a large number of smart people held the opposite opinion? These were not just travelers who claimed that the expressions of the faces of the Japanese, or of the Chinese, or of representatives of other cultures have different meanings. Birdwistel, a respected anthropologist who specialized in the study of facial expressions and gestures (protege Margaret Mead), wrote that he rejected Darwin's ideas when he discovered that in many cultures people are smiling, even feeling unhappy.

[6] Birdwistel's statement corresponded to the point of view that dominated the anthropology of cultures and, for the most part, in psychology as a whole, according to which everything of social importance should be a product of learning and, thus, vary from culture to culture.

I reconciled our conclusions about the universality of expressions of emotions with Birdwhistel's statements about the difference between these expressions in different cultures using the idea of the

rules of display . These rules, acquired as a result of social learning and often changing from culture to culture, determine how facial expressions should be managed and who and when and to whom can show one or another emotion. It is thanks to these rules in most public sporting events that the loser does not show the sadness or disappointment that he actually experiences. The rules of display are embodied in the typical order of the parents: "Remove this smug smile from the face." Such rules may require that we weaken, strengthen, completely conceal, or mask the expression of that emotion that we actually experience.

[7] I checked this wording in a number of studies that showed that the Japanese and Americans had the same facial expressions when they were

alone watching films about surgical operations and catastrophes, but when they watched the same films in the presence of a researcher, the Japanese were more than Americans masked the expression of negative emotions on their faces with a smile. Thus, in private, a person shows innate expressions of emotions, and in humans - controlled expressions.

[8] Since anthropologists and most travelers observed precisely public behavior, I had my own explanations and evidence of its use. On the contrary, symbolic gestures, such as affirmative or negative shakes of the head or a thumb raised in a fist, in a fist, are certainly specific to this culture.

[9] In this, Birdwhistle, Mead, and most other researchers of human behavior were certainly right, although they were mistaken about expressing emotions on their faces.

But there was one loophole here, and if I could see it, you could see Mead and Birdistel, who, as I knew, were looking for any way to question my results. All the people I had to examine (and Isard) could learn the Western way of expressing emotions on the face thanks to the films he had seen on the cinema and television with Charlie Chaplin and John Wayne. Learning through the mass media or contacts with representatives of other cultures could explain why people from different cultures equally appreciated the emotions in the photographs shown to them. I needed a culture that was visually isolated from the rest of the world, whose representatives would never have seen any movies, television programs, magazines, and, if possible, no people from any other society. If they evaluated the expressions of emotions in the photographs shown to them in the same way as the residents of Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Japan and the USA, then I would be on a horse.

The person who introduced me to the culture of the Stone Age was a neurologist Carlton Gaidusek, who had worked for more than ten years in the most remote parts of New Guinea. He tried to find the cause of a strange disease called

kuru , which destroyed about half of the representatives of one of such small nations. People believed that this disease was sent to them by an evil wizard. By the time I first arrived on the island, Gaidusek had already found out that the cause of the disease was a delayed-action virus with a long incubation period. In local residents, the symptoms of the disease caused by this virus began to appear several years after infection (the virus that causes AIDS acts in a similar way). But Gaidusek did not yet know how this virus is transmitted. (It turned out that the virus was transmitted due to the habit of cannibalism. These people did not eat their enemies, who died in the battle and were supposed to be healthy and strong. They only ate their friends who died from some disease, in particular from kuru. They ate raw meat, and therefore the disease spread very quickly. A few years later, for the discovery of slow viruses, Gaidusek was awarded the Nobel Prize.)

Fortunately, Gaidusek understood that the cultures of the Stone Age would soon disappear completely, and therefore spent more than a hundred thousand feet of film on the filming of several films about the daily life of two endangered cultures. He himself has never seen his films: after all, it would have taken almost six weeks to watch all the films he shot. That was the situation when I appeared on the scene.

Delighted by the fact that at least someone had a scientific interest in his films, Gaidusek put at my disposal the films he had shot, and my colleague Wally Frisen and I spent a full six months studying them. The films contained two very strong evidence of the universality of the expression of emotions on the face. First of all, we never had to see unfamiliar expressions. If facial expressions were absorbed exclusively through learning, then these people, completely isolated from the rest of the world, would demonstrate new expressions that we have never seen before. But we did not see such expressions.

However, there is still the possibility that these familiar facial expressions signal completely different emotions. But, although it was not always clear from the films what happened to the person before and after his expression appeared on his face, the local residents interviewed by us confirmed the correctness of our interpretations. If facial expressions signaled different emotions in different cultures, then it would be impossible for a stranger who is completely unfamiliar with this culture to correctly interpret the expressions he saw.

I tried to think about how Birdwistel and Mead would have challenged this statement. I imagined how they say: “It doesn’t matter that you didn’t see the new expressions; just the ones you saw really have a different meaning. You guessed them correctly because you received a hint from the social context in which they originated. You have never seen an expression that would be isolated from what happened before, after, or at the same moment. But if you saw him, you would not be able to determine what it means. " To close this loophole, I invited Sylvanas, who lived on the East Coast, to spend a week in my laboratory.

Before his arrival, we edited films in such a way that he could see only the expressions themselves, isolated from their social context, that is, in fact, only close-up faces. But Sylvan did not have any problems. Each of his interpretations fit well the social context that he did not see. Moreover, he knew exactly how he received the information. Wally and I could only feel that the emotional message was conveyed by each expression, but our assessments were intuitive; as a rule, we could not say exactly which message sent the face, unless there was a smile on the face. Sylvan confidently approached the screen and precisely indicated what specific movements of the facial muscles signaled the expression of this emotion.

We also wanted to know his general impression of these two cultures. He stated that one group looked quite friendly. Members of the second group were hot-tempered by nature, very suspicious and had homosexual inclinations. With these words he described the representatives of the

Anga tribe. His assessments corresponded well with what Gaidusek, who worked with these people, told us. They periodically attacked Australian officials who tried to establish a state-owned sheep farm nearby. This tribe, according to its neighbors, was extremely suspicious. And his male half before marriage had only homosexual relationships. A few years later, the ethnologist Irenius Aibel-Eibesfeldt, who tried to work with this tribe, had to literally save his life by fleeing.

After this meeting, I decided to devote myself to the study of facial expressions. I had to go to New Guinea and try to find the facts confirming what I thought was right: that at least some expressions of emotion on the face are universal. And I had to develop an impartial method of measuring changes in the face, so that any other scientist could objectively learn from the movements of his face all that Silvan had learned through his insight.

At the end of 1967, I went to the southeast plateau of the island of New Guinea to survey the natives of the Faure tribe who lived in small villages located seven thousand feet above sea level. I did not know the Fore language, but with the help of several local young people who learned the

Pidgin language in the missionary school, I could provide a translation of the words from English to Pidgin and further into the handicap, as well as a reverse translation. I brought with me photographs of various facial expressions, most of which Silvan gave me to conduct research among literate people. (Below are three such shots.) I also took some photos of people from the Faure tribe taken from films, believing that these people would have difficulty interpreting the facial expressions of Europeans. I even feared that they generally would not be able to understand the meaning of the photos, because they had never seen anything like it before. Previously, some anthropologists have argued that people who have never seen photos need to be taught how to interpret these images. However, the Fore men did not have such problems; they immediately understood what photographs were, and, apparently, it did not matter much to them what kind of nationality the person was photographed - an American, or a Faure tribe.

The difficulty was correctly asking them to do what I needed.

They did not have their own written language, and therefore I could not ask them to select from the list the word that would describe the shown emotion. If I had to read them a list of names of different emotions, then I would have to worry about them remembering the whole list, and about the order of the words being read not affecting their choice. For these reasons, I simply asked them to come up with a story about each facial expression. “Tell me what is happening now, because of what event in the past a person had such an expression and what should happen in the near future. The procedure was similar to the slow pulling out of the teeth. I don’t know for sure if this was due to the need to work through a translator or their complete lack of understanding of what I wanted to hear from them or why I wanted to make it do it. It is also possible that inventing stories about strangers was not among the skills possessed by representatives of the Faure tribe.

I did get some stories, but it cost me a huge amount of time. After each such meeting, both I and my interlocutors felt exhausted. Nevertheless, I did not experience a lack of volunteers, although popular rumor reported that it was very difficult to complete the task that I give. However, there was a powerful incentive forcing people to agree to look at other people's photos: everyone who agreed to help me was given a bar of soap or a pack of cigarettes. These people did not make soap, so it was of great value to them. They grew tobacco, which filled their pipes, but, apparently, they liked to smoke my cigarettes more.

Most of their stories corresponded to the emotion that was supposed to be displayed on each photo. For example, looking at a picture showing what literate people call sadness, residents of New Guinea most often said that the person shown in the photo had a child. But the procedure of “drawing out” stories was very laborious, and the proof that different stories correspond to any one emotion was a difficult task. I understood that I must act in a different way, but I did not know how.

I also photographed spontaneous facial expressions and had the opportunity to record on the film the joyful glances of people who met on the road their friends from a neighboring village. I specifically created situations that could cause the desired emotions. I taped a play of two men on local musical instruments and then photographed their surprised and joyful faces while they were listening to their music and their voices recorded on a magnetic tape for the first time in their lives. Once I even attacked with a rubber knife on a local boy for fun, and at the same time a hidden camera filmed his reaction and the reaction of his friends. Everyone decided that it was a good joke. (I prudently did not depict such an “attack” on one of the adult men.) Such movie shots could not be used by me as evidence, as those who believed that the expressions of emotions on the face should be different in different cultures could always declare that I chose only those few cases where universal expressions appeared on people's faces.

I left New Guinea in a few months - this decision was easy for me, because I was thirsting for my usual human communication, which was impossible for me in the society of these people, and my usual food, because at first I mistakenly decided that I could do with local cuisine. Something that resembles some parts of asparagus, which we usually throw in the trash can, bothered us to the last degree. It was an adventure, one of the most fascinating in my life, but I was still worried that I could not gather irrefutable evidence of my case. I knew that this culture would not remain isolated for long and that there were very few other cultures like this left in the world.

Upon returning home, I became acquainted with the research method that psychologist John Dashiel used in the 1930s. to explore how well young children can interpret facial expressions. The children were too small to read, so he could not give them a list of words from which they could make a choice. Instead of asking them to invent a story - as I did in New Guinea, Deshil himself told them stories and showed a set of pictures. All that was required of them was to choose a picture corresponding to the story being told. I realized that this method would suit me. I looked at the stories told to me by the inhabitants of New Guinea to select the ones that were most often used in explaining each instance of the expression of emotions. They were all quite simple: “Friends came to him, and he is very happy about it; he is angry and ready to fight; his child has died, and he is in deep sadness; he looks at something that he doesn’t like very much, or he sees something that smells very bad; he sees something new and unexpected. ”

There was a problem with the most often told story for a sense of fear — about the danger posed by a wild pig. I had to change it in order to reduce the likelihood of its application to the emotions of surprise or anger. She began to look like this: “He sits at home all alone, and there is no one in the village either. There is no knife, no ax, no bow and arrows at home. The wild pig stops in front of the door of the house, and he looks at her and feels fear. The pig stands in front of the door for a few minutes, and he looks at her in dismay; the pig does not move away from the door, and he is afraid that the pig will attack him. ”

I made a set of three photos that were supposed to be shown when reading one of the stories (an example is given below). The subject was only required to indicate one of the photographs. I prepared many sets of photos, because I didn’t want one of them to appear more than once and a person could make a choice by means of an exception: “Oh, I already saw this when I listened to a story about a dead child, and this one when I was told about the readiness to attack the offender; so this photo has to do with a wild pig. ”

I returned to New Guinea at the end of 1968 with my own stories and photos and with a few of my colleagues who were supposed to help me collect data.

[10] (This time I took with me a large supply of canned food.) The news of our return quickly spread around the island, because, apart from Gaidusek and his operator Richard Sorenson (who helped me a lot on my first visit), very few foreigners, Visiting New Guinea once, they came there again. At first, we ourselves drove through several villages, but after it became known that this time we ask you to complete a very easy task, we began to receive residents of the most remote corners of the island. They liked our new assignment and the opportunity to get a bar of soap or a pack of cigarettes.

I deliberately made sure that no one from our group could make unintended clues to our subjects about what kind of emotion a particular photograph corresponds to. The sets of photos were pasted on transparent plastic pages, while the numeric code written on the back of each image could only be visible on the back of the page. We tried to make it impossible to find out which code matched each expression. Therefore, the page was turned to the subject in such a way that the person recording the answers could not see the front side of the page. The story was read, and the subject pointed to the corresponding photo, and one of us recorded the code of the picture chosen by the subject.

[eleven] In just a few weeks, we surveyed more than three hundred people, i.e., about 3% of all representatives of this culture, and the data obtained was quite enough for statistical analysis. The results did not cause doubts for the emotions of joy, anger, disgust and sadness. Fear and surprise were virtually indistinguishable: when people heard a terrible story, they were equally likely to choose the expression of fear and the expression of surprise, and the same thing was observed when they heard an amazing story. But fear and wonder differentiated from anger, disgust, sadness, and joy. Until now, I do not know why these people did not distinguish between fear and surprise. Perhaps the problem was in our stories, and perhaps these two emotions were so closely intertwined in the lives of these people that they became almost indistinguishable. In cultures with a predominantly literate population, people clearly distinguish fear from surprise.

[12] All of our subjects, with the exception of twenty-three, have never seen movies, TV shows or photographs, have not spoken English or

Pidgin and have not understood these languages, have never been to locations in the west of the island or the main city of their province and have never worked on Europeans. The twenty-three people who constituted the exception saw the movies, spoke English, and attended a missionary school for more than a year. The results of the study did not reveal any differences between the majority of subjects, who had little contact with the outside world, and the few who had these contacts, as well as between men and women.

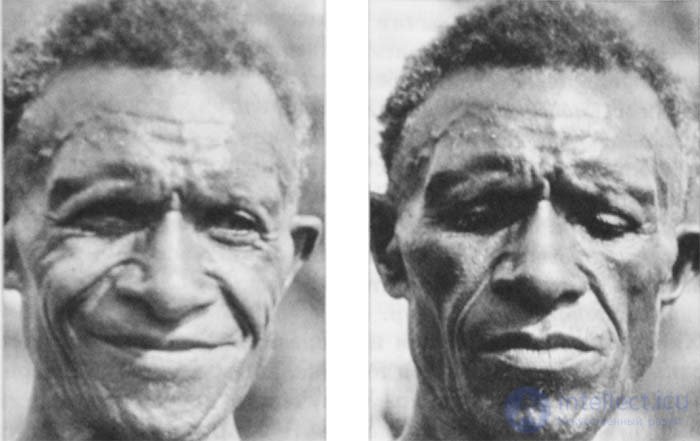

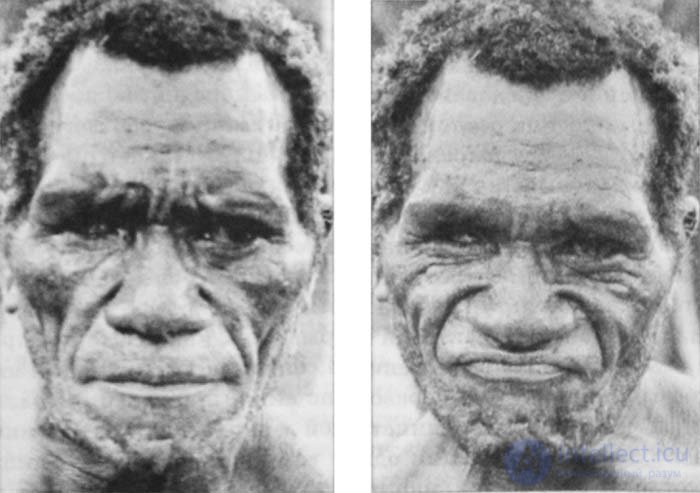

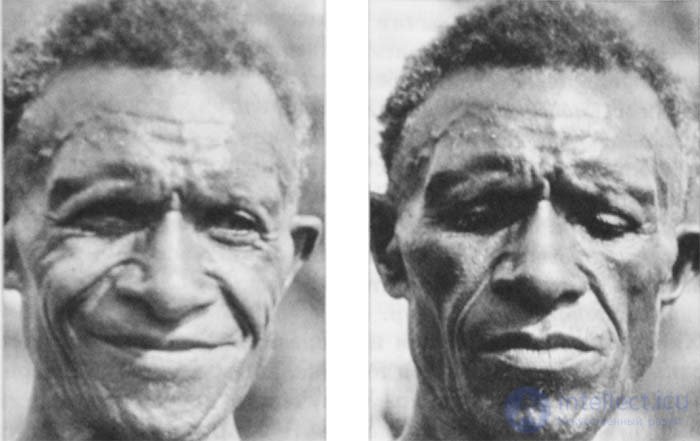

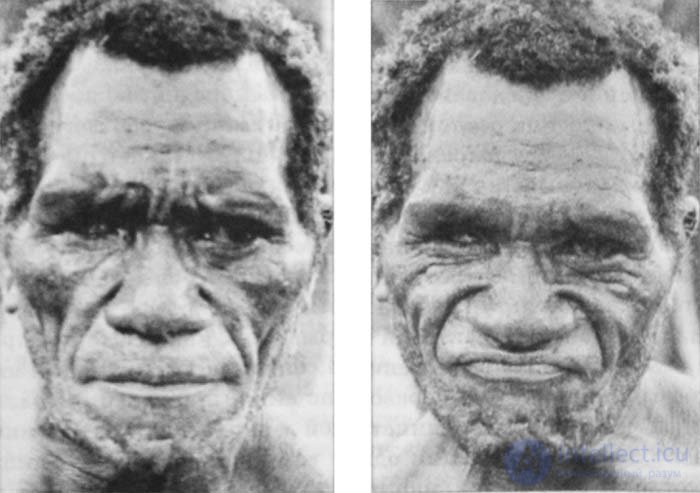

We conducted another experiment, which was not so simple for the subjects. One of the people who spoke pidgin read a story to the audience, and then asked them to show what their face would look like if this story happened to them. I filmed videos of how these people, none of whom participated in the first experiment, gave the required expressions to their faces. Later, these unedited videos were shown to college students in the United States. If expressions of emotions changed from culture to culture, then these students could not interpret them correctly. But the Americans managed to identify all emotions except fear and surprise - they confused them just like the people of New Guinea. Below are four examples of how Guineans express their emotions.

I published the results of our research at the annual national conference of anthropologists in 1969. For many, our results were an unpleasant surprise. These scientists were firmly convinced that the behavior of a person is entirely determined by his upbringing, and not by his innate qualities; it followed that, despite my evidence, the expressions of emotions must be different in different cultures. The fact of detecting cultural differences in the

management of facial expressions in my experiment with Japanese and American students was considered insufficiently convincing.

The best way to dispel the doubts of opponents was to completely repeat all the research in another primitive isolated culture. Ideally, someone else had to repeat the research - who would like to prove me wrong. If such a person found the same thing that I discovered, it would greatly strengthen my position. Thanks to another lucky coincidence, anthropologist Karl Haider has brilliantly performed this task.

Haider recently returned from Indonesia, more precisely from that part of the country which is now called Western Arian. There he spent several years studying another isolated group of Dani natives.

[13] Haider told me that something was wrong in my research, because the people of the Dani tribe do not even have words for emotion. I introduced him to all the materials of my research and offered to repeat my experiments the next time I visited this tribe. His results coincided exactly with mine - even with regard to the inability to clearly distinguish between surprise and fear.

[14] Nevertheless, even today not all anthropologists are convinced of the correctness of my conclusions. Several psychologists known to me, mainly dealing with language issues, indicate that our research among literate people, during which we asked respondents to call an emotion corresponding to a specific facial expression, does not confirm the principle of universality, since the words defining each emotion are not have a perfect translation to other languages. The way emotions are displayed in language is, of course, a product of culture, not evolution. But the results of a survey of more than twenty literate cultures of the West and the East suggest that the opinion of the majority of cultural representatives about which emotion manifests itself in a given facial expression is the same. Despite the problem of translation, we never had a situation in which most people in two cultures attributed different emotions to the same facial expression. Never! And, of course, our conclusions were based not only on those studies, in which people had to describe the photograph in a single word. In New Guinea, we used stories to describe the event that caused the emotion. We also asked them to depict emotions. And in Japan, we actually measured the movements of the face itself, thus showing that when people are alone, then when watching an unpleasant movie, they have the same facial muscles, no matter who these people are - Japanese or American.

Another critic spoke disdainfully about our research in New Guinea on the grounds that we did not use specific words, but stories describing social situations.

[15] He argued that emotions are words, although in reality this is not the case. Words are only signs of emotions, not emotions per se. Emotion is a process, a special type of automatic evaluation, bearing the imprint of our evolutionary and individual past; In the course of this assessment, we feel that something important is happening for our well-being and a set of physiological changes and emotional reactions interact with the current situation. Words are just one of the ways to display emotions, and we actually use them when we are emotionally excited, but we cannot reduce emotions to words only.

No one knows for sure what message we automatically receive when we see someone's facial expression. I suspect that words such as “anger” or “fear” are not among the messages we usually transmit when we are in the right situation. We use these words when talking about emotions. More often, the message we receive is very similar to the one we received thanks to our stories - not an abstract word, but a certain feeling of what a person is going to do at the next moment, or what caused a person to experience some kind of emotion.

Another completely different type of evidence also supports Darwin’s assertion that facial expressions are universal and are the result of our evolution. If expressions do not need to be absorbed, then those who are born blind should demonstrate the same expressions of emotion as those who were born sighted. Many studies on this topic have been conducted over the past sixty years, and their results have consistently supported this assumption, especially with regard to spontaneous facial expressions.

[sixteen] The results of our cross-cultural research have stimulated the search for answers to many other questions about expressions of emotion: how many expressions can people give to their face? Provide facial expressions of authentic or misleading information? Can people lie by the face, just as they lie by words? We had so much to do and so much to know. Now we have the answers to all these questions, like many others.

I found out how many expressions our face can take: it turned out that more than ten thousand, and I identified those that are most important to our emotions. More than twenty years ago, Wally Frizen and I compiled the first atlas of a human face, which consisted of verbal descriptions, photographs and sequences of motion pictures and made it possible to measure facial movements in anatomical terms. Working on this atlas, I learned how to perform any muscular movements on my own face. Sometimes, in order to verify that the movement I was performing was caused by a contraction of a particular muscle, I pierced the skin of the face with a needle in order to provide electrostimulation and contraction of the muscle creating the desired expression. In 1978, a description of our facial movement measurement technique, the

Facial Action Coding System , was published as a separate book. Since then, this tool has been widely used by hundreds of scientists from different countries to measure facial movements, and computer specialists are actively working on how to automate and speed up such measurements.

[17] Over the years, I used FACS to study thousands of photographs and many thousands of facial expressions taken on film and videotape, and measured every muscle movement for every emotion expression. I sought to learn about emotions as much as possible by measuring the expressions of the patients of psychiatric hospitals and people with cardiovascular diseases. I also studied normal people who showed up on CNN news or were participants in my laboratory experiments to provoke emotions.Over the past twenty years, I have collaborated with other scientists to find out what is happening in our body and our brain when an expression of some kind of emotion appears on our face. Just as there are different expressions for anger, fear, disgust and sadness, there are also different profiles of physiological changes in the organs of our body that generate their own unique sensations for each emotion. Science is only now beginning to determine the models of the brain that underlie the manifestation of each emotion. [18] Using FACS, we learned to detect signs on the face that indicate that a person is lying. What I called microexpressionsi.e. Very fast movements of the face, lasting less than 1/5 of a second, are important sources of information leakage, which allows you to find out what kind of emotion a person is trying to hide. Insincere facial expressions can expose themselves in different ways: they are usually slightly asymmetrical and their appearance and disappearance from the face is too abrupt. My research into detecting signs of lies has led to my cooperation with judges, lawyers and police officers, as well as with the FBI, the CIA and other similar organizations from friendly countries. I taught all these people how to determine as accurately as possible whether a person is telling the truth or lying. This work helped me get the opportunity to explore the facial expressions and emotions of spies, murderers, embezzlers, foreign national leaders and many other people,with whom the professor of psychology usually never meets in person. [nineteen] When I wrote more than half of this book, I was given the opportunity to spend five days in the company of His Holiness Dalai-Lama, to discuss with him the problem of destructive emotions. In our conversations took part six more people - scientists and philosophers, who also expounded their views. [20]Acquaintance with their views and participation in the discussion allowed me to get acquainted with new ideas that I reflected in this book. It was then that I first learned about the views on the emotions of Tibetan Buddhists, and these views turned out to be completely different from those that we developed in the West. I was surprised to find that the ideas I presented in sections 2 and 3 turned out to be compatible with the views of Buddhists, and the views of the Buddhists suggested the expansion and refinement of my ideas, which made me significantly change these sections. I learned from His Holiness the Dalai Lama about many different levels of knowledge, from empirical to intellectual, and I believed that my book would greatly benefit from the knowledge I gained. [21]This book is not about Buddhist views on emotions, but I do point out from time to time to the existing coincidences of our views and to those moments when, thanks to these coincidences, I came up with original ideas. One of the new areas of research of particular interest to scientists is associated with the study of the mechanisms of the emergence of emotions. [22]Much of what I wrote about here is based on the results of such research, but we still don’t know so much about our brain to answer many of the questions discussed in this book. We really know a lot about emotional behavior - quite enough to answer the most important questions about the role of emotions in our daily life. What I’m talking about in the following sections is mainly based on my own research into emotional behavior, during which I studied in detail the features I’ve seen in different emotional situations in many different cultures. Having understood this material, I decided to write about what I think people should know in order to better understand their emotions.Although the basis for writing this book was provided by my research, I deliberately went beyond what science has proven to include in the book also what I think is true, but it is still not scientifically proven. I addressed several questions that I think are interesting for people who want to make their emotional life more comfortable. Work on the book has given me a new understanding of emotions, and I hope that this new understanding will appear now with you.

Спасибо все понятно

Comments

To leave a comment

Psychology of emotions

Terms: Psychology of emotions