Lecture

A speech figure ( rhetorical figure , stylistic figure ; lat. Figura from ancient Greek σχ μα) is a term of rhetoric and stylistics, denoting various turns of speech that give it stylistic significance, figurativeness and expressiveness, change its emotional coloring. The figures of speech serve to convey the mood or enhance the effect of the phrase, which is commonly used for artistic purposes both in poetry and in prose.

The ancient rhetoricians considered rhetorical figures as certain deviations of speech from the natural norm, “ordinary and simple form,” a kind of artificial decoration for it. The modern view, on the contrary, proceeds rather from the fact that figures are a natural and integral part of human speech.

Among the figures of speech from the time of antiquity, there are tropes (the use of words in a figurative sense) and figures in the narrow sense of the word (methods of combining words) - although the problem of clearly defining and distinguishing between the two has always remained open.

The ancient Greek philosopher and orator Gorgiy (V century BC) was so famous for his innovative use of rhetorical figures in his speeches that for a long time they were called “Gorgian figures”.

The figures of speech were considered by Aristotle (IV century BC. E.) And were developed in more detail by his followers; so, Demetrius of Falersky (IV — III centuries BC.) introduced a division into “figures of speech” and “figures of thought”.

Rhetoric is actively developing in ancient Rome: in the I century BC. er figures and the use of words in a figurative sense are considered in the anonymous treatise “Rhetoric to Gerennia” and in Cicero (who adheres to the division of figures into “figures of speech” and “figures of thought”, without seeking to systematically classify them) ; in the 1st century AD er Quintillian has a division into four types of figures: addition , subtraction , replacement (one word for another), permutation (words for another place) .

In the Hellenistic era, and then in the Middle Ages, scientists and scholastics delve deeper into the detailed classification of all sorts of tropes and figures, of which more than 200 varieties have been allocated as a result.

Main articles: Trail , Figure (rhetoric)

The figures of speech are divided into paths and figures in the narrow sense of the word. If the tropes are understood as the use of words or phrases in an improper, figurative meaning, allegory, then the figures are techniques of a combination of words, syntactic (syntagmatic) organization of speech. At the same time, the distinction is not always unambiguous, there are doubts regarding some figures of speech (such as epithet, comparison, paraphrase, hyperbole, litho): refer them to the figures in the narrow sense of the word or to the trails. M.L. Gasparov regards the trails as a type of figure - “figure rethinking”.

There is no generally accepted systematics of figures of speech, in different grammar schools there are different terminology (names of figures) and principles of their classification.

Traditionally, figures of speech (mostly figures in the narrow sense of the word) were divided into words and thought figures . The difference between them is manifested, for example, in the fact that replacing a word with a close in meaning destroys the figures of the word, but not the figures of thought. Thought figures are easily translated into another language, unlike word figures. In some cases, the assignment of a figure to one or another type is not obvious (for example, in the case of antithesis).

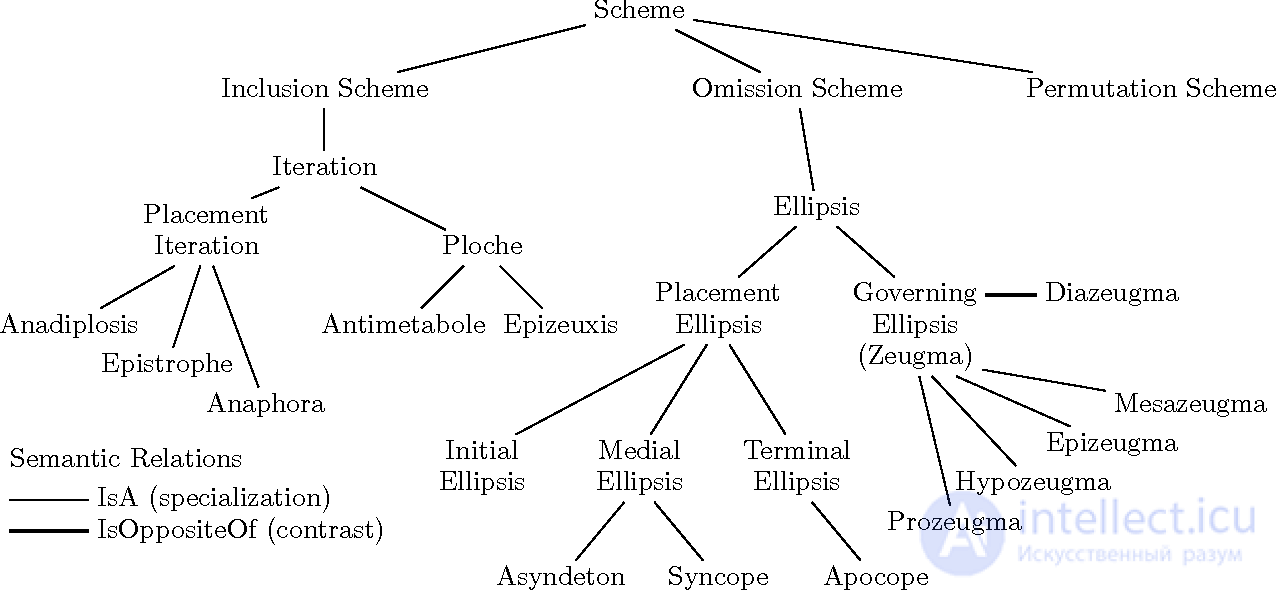

Following Quintillian, the figures (mainly the figures of the word) were divided into four groups (“ Quadripartita ratio ”), highlighting the figures formed by: additions ( adiectio ), subtractions ( detractio ), substitutions ( immutatio ), permutations ( transmutatio ). [five]

Some common figures of speech in the traditional classification:

- Figures:

- Word shapes :

- Addition figures : various kinds of repetitions, precise and inaccurate: anadiplosis, mezarhia, anaphora, epiphora, simplock, gradation, polyptoton, multi-union, pleonasm

- Decrease figures : ellipse, lack of union, zeugma

- Permutation (placement) patterns: parallelism (types: antithesis, isocolone, homeotelewton), inversion (including hyperbaton), chiasm, parentesis

- Thought figures :

rhetorical question, rhetorical exclamation, rhetorical appeal; silence, oxymoron

- Paths:

metaphor, metonymy, synecdoche, katahreza; allegory, paraphrase, epithet, irony, hyperbole, litotes, paronomasia, personification

In the literature of the 20th century, figures are often divided into semantic and syntactic. Thus, Yu. M. Skrebnev calls semantic figures: comparison, ascending and descending gradation, zeugma, pun, antithesis, oxymoron; syntactic: subtraction figures (ellipsis, aposiopesa, prosiopesa, apocoque, asyndeton), addition figures (repetition, anadiplosis, prolepsis - simultaneous use of a noun and a substitute pronoun, polysindeton), various types of inversions, rhetorical question, parallelism, pausing, polysindeton), various types of inversions, rhetorical question, parallelism, numerics, rhythmic question, parallelism, chasmmas, chiasmas, and chiasmas. simploku. [6]

Scientists from the Mu Group went further in this direction. In the book “General Rhetoric” (1970), they proposed a general classification of rhetorical figures and tropes according to the level of language operations, dividing them into four groups: metaplasmas (morphology level - operations with phonetic and / or graphic appearance of a language unit), metataxis (operations at the level of syntax), metasememes (operations at the level of semantics — values of a language unit), and metalogisms (logical operations). The operations themselves were divided into two main types: substantive and relational. "The first operations change the substance of the units to which they are applied, the second changes only the positional relationship between these units." Substantial operations include: 1) a decrease, 2) an addition, and 3) a decrease with an addition (to what combination is the replacement of Quintillian); the only relational operation is 4) permutation. [7]

This term has other meanings, see Figure.

The figure ( figure of speech in the narrow sense of the word, rhetorical figure , stylistic figure ; lat. Figura from the ancient Greek σχῆμα) is a term of rhetoric and stylistics denoting the methods of syntactic (syntagmatic) speech organization that, without adding any additional information, give artistic speech and expressive qualities and originality.

Unlike the tropes, which represent the use of words in a figurative sense, figures are the techniques of combining words. Together with the tropes, the figures are called “figures of speech” in the broad sense of the word. In this case, the delimitation of the figures from the tropes in some cases causes controversy.

Figures are known since antiquity. The ancient Greek sophist Gorgius (5th century BC) was so famous for the innovative use in his speeches of rhetorical figures, especially isocolone (rhythmic-syntactic similarity of parts of the period), homeotelton (consonance of the endings of these parts, i.e. internal rhyme) and antitheses that for a long time they were called "Gorgian figures."

Adinatón (from the ancient Greek ἀδύνᾰτον "impossible") is a figure of speech in the form of a hyperbole, when something impossible or very difficult to implement is compared with an abstract example and a strong exaggeration, with some unreal situation, with something which by the nature of things cannot be. Rhetorical method of bringing the comparison to the impossible, often with a humorous effect.

Typical examples:

This term has other meanings, see Amplification.

Amplification (lat. Amplificatio “expansion”) is a stylistic figure, representing a series of repetitive speech constructions or individual words.

Amplification is one of the means of enhancing the poetic expression of speech. Amplification as a stylistic device is expressed, for example, in the accumulation of synonyms, the antithesis, or may take the form of enhancement, that is, the arrangement of expressions relating to one subject, according to the principle of increasing their significance, emotional efficacy, etc.

Amplification is a rhetorical device, sharply beating on the increase in perception, and that's how its speakers regard it as, say, the great orator of antiquity, Cicero, who found that amplification is a triumph of eloquence.

A whole poem can be based on amplification. Such, for example, is A. Pushkin’s poem “Three keys” [1] or “Big Elegy to John Don” Brodsky I. A. [2]

For everything, for all I thank you:

For the secret torment of passion,

For the bitterness of tears, the poison of a kiss,

For revenge of enemies and slander of friends;

For the heat of the soul, squandered in the wilderness ...- Lermontov M. Yu. Gratitude

When the foliage is raw and rusty

Rowanwood zaaleet bunch, -

When the executioner hand bony

The last nail is put in the palm

When over the ripples of rivers lead,

In raw and gray height,

Before the face of the homeland harsh

I will rock on the cross ...- Block A. A.

Takes -

like a bomb

takes -

like a hedgehog

like a razor

double edged

beret,

like an explosive

in 20 stings

snake

two meters tall.- Mayakovsky V. V. Verses about the Soviet passport

... I cared a secret idea,

I suffered, languished and suffered ...- Lermontov M. Yu. Mtsyri

He was like a clear evening:

Neither day nor night - neither darkness nor light! ...- Lermontov M. Yu. Demon

Do you look into yourself? - there is no trace of the past:

And joy, and torment, and everything there is insignificant ...

Anadiplosis (from the ancient Greek ἀναδίπλωσις “doubleness”) is a repetition of one or several words in such a way that the last word or phrase of the first part of the speech segment is repeated at the beginning of the next part. Thus, they are connected in a single unit. In modern verse terminology, the repetition of the end of a verse at the beginning of the next. Reception is known since ancient times.

Repeatedly found in biblical psalms:

... where will my help come from?

My help is from the Lord ...- Ps. 120: 1-2

Behold, our feet are in your gates, Jerusalem,

Jerusalem, arranged as a city, merged into one ...- Ps. 121: 2-3

... the flow would have passed over our soul;

would pass over our soul stormy waters.- Ps. 123: 4-5

My soul awaits the Lord more than the watchmen in the morning, more than the watchmen in the morning.

May Israel trust ...- Ps. 129: 6-7

Examples of anadiplosis in folk Russian poetry:

Let us guys write a petition,

Petition write to send to Moscow.

To send to Moscow, to give to the tsar in hands.

On the cross sits a little birdie,

Free ptashechka boron cuckoo

Highly sitting, looking away.

Looking far behind the blue sea.

He kissed her white hands,

The hands are white, the fingers are thin,

Fingers are thin in gold rings.

An example of anadiplosis in Russian book poetry:

I climbed the tower, and the steps trembled.

And the steps trembled under my foot.- K. Balmont

By squeezing anadiplosis, we get an initial rhyme.

Anakoluf (from other Greek, ἀνακόλουθον “anacoluf”, literally, “inconsistency”) is a rhetorical figure consisting in the wrong grammatical coordination of words in a sentence, either by negligence or as a stylistic device (stylistic error) to impart a character to a speech character. [1] By its nature, the anacolyth is excretory in nature against the background of grammatically correct speech. Anakolufu is close to syntactic zaum (text built on the systematic violation of syntax rules) and errative (text built on breaking spelling rules).

Anakolof, in particular, is used for the speech characteristics of a character who is not very good at speaking a language (a foreigner, a child, just a poorly cultured person). Colonel Skalozub in the comedy “Woe from Wit” Griboyedov says “I am ashamed of myself, as an honest officer” (instead of “I am ashamed of myself, as an honest officer”). In Tolstoy, the chairman of the court, a man apparently educated in French, says, “Do you want to make a question?” (“Resurrection.” Part One. Chapter XI).

In Bulgakov, Professor Preobrazhensky points out the presence of an error in the statement of the proletarian Shvonder:

“We, the management of the house,” Shvonder spoke with hatred, “came to you after the general meeting of the tenants of our house, at which there was a question about compacting the apartments of the house ...

- Who stood on whom? - shouted Philipp Philippovich, - take the trouble to express your thoughts more clearly.

- "Dog's heart"

Anacoluf is also widely used as a humorous, satirical image:

Driving up to this station and looking at nature through the window, my hat fell off

- Chekhov A.P. "Book of Complaint"

I recently read with a French scientist that the lion's muzzle is not at all like a human face, as scientists think. And for that we will talk. Come on, take mercy. Come here tomorrow for example.

- Chekhov A.P. “A letter to a learned neighbor”

However, grammatical incorrectness, attracting attention to itself, is capable of giving speech more expressive in nature, and therefore writers of different epochs and trends also use Anacoluf in the author's speech to create an emotional accent:

The smell of the shag felt from there and with some sour soup made life in this place almost unbearable

- Pisemsky A. F. “The Sin of Ages”

The one that the bull in Lesbos suddenly saw roared and, swirling towards it from the hill, poked its horn, entering under its arm

- Solovyov S. V. “Amorth”

This term has other meanings, see Anaphora (meanings).

Anaphora (from ancient Greek. Ἀναφορά “anaphora”, literally “stealing”) is a stylistic figure consisting in the repetition of similar sounds, words or groups of words at the beginning of each parallel series, that is, in repetition of the initial parts of two or more relatively independent segments of speech (half-silence, verses, stanzas or prose passages). [1] [2] The sound anaphora is a feature of the alliterative verse, but it is sometimes found in metric verses (see below):

Repetition of the same combinations of sounds:

Thunderstorm demolished bridges,

Gro ba from the blurred graveyard- Pushkin A.S. The Bronze Horseman

Repetition of the same morphemes or parts of words:

Black eyed girl,

Black- maned horse.- Lermontov M. Yu. Prisoner

Repetition of the same words:

It was not in vain that the winds blew,

Not in vain was the storm.- Yesenin S. A. The winds did not blow in vain

Repetition of the same syntactic constructions:

Do I wander along noisy streets,

I enter into a crowded temple,

I’m sitting between the insane young men,

I surrender to my dreams.- Pushkin A. S. Do I wander along the noisy streets

Land!..

From moisture snow

She is still fresh.

She wanders by herself

And breathes like dezha.

Land!..

She runs, runs

A thousand miles ahead,

Above her lark trembles

And she sings about her.

Land!..

More beautiful and visible

She lies around.

And there is no better happiness - on it

Until death live.

Land!..

To the west, to the east,

To the north and south ...

Crouched, hugged Morgunok,

Yes, not enough hands ...- Tvardovsky A.T.

Combinations of the above types of anaphor are possible. For example:

While not thirsty machine gun

Gutting the thick of human

Live and live Omet

Among the mills, the harvest is chewing.

While not commanding commander

Cut the enemy with one blow,

Barns are filled with good reason

Fields of gold-bearing gift.

Until the enemy thunder says

His opening remarks

In the fields there can be no other

Catcher spaces than agronomist.- N. Tikhonov

A very rare trick is the use of rhythmic anaphora. In the poem below, the rhythmic anaphora consists in pausing the third portion of the amphibrachic foot in even verses:

The sun is up. Port | rety in those. / \

C | dish / \ at | lying and | modest you | / \ / \

Sta rushke yawn. By | fire / windows / \

Walked / \ in those | far | rooms. | / \ / \

Neither | as a comrade | ra you do not | chase you | away, - / \

According to | \ / and the light of all | asks |. / \ / \

Look you do not | dare on | moonlight | night, / \

Ku | yes / \ du | sha is transferred? ... | / \ / \- Fet A. A.

Anaphora can be considered as one of the types of consistent proposals. As a form of connection between the parts of the sentence and the whole sentences, the anaphora is found in Old German poetry and forms a special stanza “anaphoric trisylla.”

Often anaphora connects with another rhetorical figure - gradation, that is, with a gradual increase in the emotional nature of words in speech, for example, in Edde: "Livestock dies, a friend dies, and the person dies."

Anaphora is found in prose speech. Forms of greeting and farewell are most often built anaphoric (in imitation of the people at the Minnesingers, troubadours, as well as the poets of the new time). It is interesting to note in its anaphor its historical and cultural lining.

It was considered even more important to have once a completely identical appeal to the gods, in order not to anger any one of them, or to the rulers sitting together (for example, at a trial, a military meeting, at a feast):

Most honorable, respectable, highly learned and wise gentlemen burgomasters and ratmans and most respectable, eminent and prudent gentlemen eltermans and old people along with all the burghers of all three guilds of the royal city of Revel, my overlords and all gracious sovereigns and good friends.

- Balthazar Russow, "The Chronicle of the Province of Livonia"

Antithesis , antithesis (from the ancient Greek. Ἀντίθεσις “opposition”) is a rhetorical opposition, a stylistic contrast figure in artistic ororical speech, consisting in a sharp opposition of concepts, positions, images, states connected by a common construction or internal sense [1] .

The figure of the antithesis can serve as a principle for constructing whole poetic plays or separate parts of works of art in verses and prose. For example, Petrarch F. has a sonnet (translated by Verkhovsky Yu. N.), entirely built on antithesis:

And there is no peace — and there are no enemies anywhere;

I am afraid - I hope, I am ashamed and burning;

I dust in the dust - and I fly in the sky;

Everyone in the world is alien - and the world is ready to hug.

I do not know her captivity;

They do not want to own me, but oppression is severe;

Cupid does not destroy and does not tear the shackles;

And there is no end to life and torment - the edge.

I can see without eyes; mute, let out a howl;

And the thirst for doom - I pray to save;

I possessed myself, and I love all the others;

Suffering is alive; with a laugh, I weep;

And death and life are cursed with anguish;

And this is the fault, O Donna, - you!

Descriptions, characteristics, especially the so-called comparative ones, are often built antithetical.

For example, the characterization of Peter the Great in Pushkin’s Stansy A. S .:

That academician, the hero,

That the navigator, the carpenter ...- Pushkin A.S. Stanzy

Sharply emphasizing the contrasting features of the compared members, the antithesis, precisely because of its sharpness, is distinguished by too persistent persuasiveness and brightness (for which romantics loved this figure so much). Many stylists, therefore, treated the antithesis negatively, but on the other hand, poets with rhetorical pathos, such as Hugo or Mayakovsky, are noticeably addicted to it:

Our strength is true

yours - laurels chimes.

Yours is incense smoke,

our factory smoke.

Your power is a gold piece

Ours is a red one.

We will take,

will take

and win.

The symmetry and analytical nature of the antithesis make it very appropriate in some strict forms, such as, for example, in the Alexandrian verse, with its clear division into two parts.

The sharp clarity of the antithesis makes it also very suitable for the style of works that seek direct persuasiveness, such as in declarative-political works, with social tendencies, agitation or moralistic, etc. The examples include:

Proletarians have nothing to lose in it except their chains. They will gain the whole world.

- The Communist Manifesto

Who was nobody will become everything!

- Internationale

The antithetic composition is often observed in social novels and plays with a contrasting comparison of the life of various classes (for example: “Iron Heel” by G. London, “The Prince and the Pauper” by Mark Twain, etc.); antithesis can underlie works depicting moral tragedy (for example: Dostoevsky's Idiot), etc.

In this social key, the use of antithesis in a very peculiar way used N. Nekrasov in the first poem from the cycle “Songs”:

People have something for their cabbage soup - with a salt bean,

And we have something in cabi - a cockroach, a cockroach!

People have godfathers - kids give,

But our godfather’s bread will come!

People on their minds - exercise with godfathers,

And on our mind - would not go with the bag?

Antiteton , syneresis (from the ancient Greek. Ἀντίθετον "opposition", συναίρεσις "comparison") is a rhetorical figure, opposing two thoughts, but not forming an imaginary contradiction, unlike the antithesis. For example, a contradiction is not formed if not opposed to the opposite qualities of one object, but the qualities of two different objects:

Ivan Ivanovich’s head is like a radish, tail down; head of Ivan Nikiforovich on radish tail up. N.V. Gogol. The story of how Ivan Ivanovich fell out with Ivan Nikiforovich.

“One of them was kind in giving, the other was cunning in acceptance, everyone wanted it, they avoided that he should not see them. The shame of this was all sweet, the shamelessness of himself pleased him, for others - bitterly. ” [one]

Original text (in Ukrainian) [show]

Also, there is no contradiction if the second opposing phenomenon is a consequence of the first:

“[Christ] lowered himself to lift us up. Put yourself in danger to take us under protection; was bound to deliver us; was torn to renew us; shed blood to cure us; hung on the cross to eliminate the most fierce tyranny that oppressed us. Finally, he wished death to cook for us the eternal in his father. ” [one]

Original text (in Ukrainian) [show]

However, such usage of the term antitetton is not the only one. Thus, sometimes antithesis is called antithesis or an oxymoron [2] .

Apokopa (from the ancient Greek. Ἀποκοπ ус "truncation") is a phonetic phenomenon denoting the loss of one or several sounds at the end of a word, as a rule of a final unstressed vowel, resulting in the reduction of a word. Refers to metaplasmas.

In Italian, in addition to elision (loss of the last vowel), there are also loss of whole syllables that are not marked with an apostrophe (as in the case of elision ). This phenomenon can be called in different ways:

* apheresis (afèresi) - lowering the syllable at the beginning of a word;

* Sincope (sincope) - lowering the syllable in the middle of the word;

* apocope (apocope, also troncamento) - lowering the last syllable (without joining the next word).

In Greek verse, it is used for meter reasons; is that when reading a vowel at the end of a word is omitted if the next word begins with a vowel. In the text is indicated by the sign of the apostrophe "'". For example: "λολλά δ᾽ ὅ γ᾽ ἐν πόντῳ πάθεν λγεα ὅν κᾰτά θυμν" (Hom. Od. I 4). In Latin verse, a similar phenomenon is elision.

The Russian verse is used for reasons of size and artistic expression. For example, in the following verse of apokop, the words “slamming / clapping”, “rumor” and “stamping” are exposed:

Here the squatting mill is dancing

And wings flapping and flapping:

Barking, laughing, singing, whistling and clapping,

People talk and horse top!- A. S. Pushkin Eugene Onegin, ch. five

In the notes to “Eugene Onegin”, Pushkin wrote: “The magazines condemned the words bang, talk and top as an unfortunate innovation. These are the root Russian. “Bova came out of the tent to cool off and heard a rumor and a horse top in the open field” (The Tale of Beauvais Korolević). Clap is used in common parlance instead of clapping, like a thorn instead of hissing ... "

A special type of apocopy can be considered acronyms, that is, abbreviations pronounced not by letter, but as an ordinary word: “TASS” (Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union), “university” (higher educational institution), etc., since the principle of pronouncing such abbreviations (lowering all (last) sounds except the first letter) is very close to the principle of the apokope (lowering several sounds or syllables at the end of a word).

A special type of apocopy is considered to be wordpersons.

In Russian, the word "apocopa" is one of the four longest (along with "kinonic", "rotator", "tartrate") words-palindromes.

Apostrophe (from ancient Greek. Ἀποστροφή "apostrophe", literally "turn"), otherwise method or metabasis (from μετάβᾰσις "transition") [1] - exclamatory rhetorical figure of speech, when the speaker or writer stops the story and turns to the missing person , as to the present or imaginary person, as a real, abstract concept, subject or quality. In dramatic and poetic works of art, the apostrophe is a rhetorical device, an appeal (often unexpected) to one of the listeners or readers, to an imaginary person or an inanimate object. The apostrophe in the Russian language is often introduced by the exclamation “O” [2] [3] [4] .

My poems! Living witnesses

For the world of shed tears!

You are born in fatal minutes

Thunderstorms

And beat the hearts of men,

Like a wave on a cliff.- N. A. Nekrasov

Sad time! Charm of the eyes!

I love your farewell beauty

I love the lush nature of fading,

In scarlet and in gold clad woods,

In their wind of the wind is noise and fresh breath,

And in the dark wavy sky covered,

And a rare ray of the sun, and the first frost,

And distant gray winter threats.- A. S. Pushkin, Autumn

Oh, summer is red! I would love you

When not hot, but dust, but mosquitoes, but flies.

You, ruining all mental abilities,

Torment us; like fields, we suffer from drought;

Just like to drink, but refresh yourself -

There is no other thought in us, and it is a pity the winter of the old woman,

And, holding her pancakes and wine,

Commemoration of her create ice cream and ice.- A. S. Pushkin, Autumn

No wonder you rushed and boiled,

Development haste, -

You accomplished your feat before the body

Mad soul!

Attraction (from the Latin. Attractio "attracting") - turnover, grammatically expressed in the absence of syntactic connection between the two members of the sentence. Examples of attraction: “killed by elephants”, “wrapped in a cup of green wine” instead — killed by elephants, wrapped in a cup of green wine. Attraction dates back to the era of domination in the language of the paratactic system. The essential feature of this system was that the subject did not allow the development of any other members except the application and the attributive adjective in a non-definitive form; The genitive form in Old Church Slavonic and Old Russian was impossible. It was impossible to say the Church of the Savior, and the Church of the Savior. The predicate could only develop additions in one case; it was impossible to say - they saw me going, - and the video of the person walking, etc. Attraction (attract, attract) is a concept denoting the appearance, when a person perceives a human being, the attractiveness of one of them for the other. Formation of affection, sympathy. This lack of syntactic perspective can be compared with the same lack of perspective in Old Russian painting. With the further development of the language and the hypothetic direction opposite to the paratactical one, the attraction was retained in the epithets. The defined word could take the form of different cases, and the complex epithet continued to remain in the nominative. In modern language, the attraction is weakened by means of prepositions: in my apartment (in my apartment), etc.

Unopportunity or asindeton (Greek ἀσύνδετον, Latin dissolutio ) - stylistic figure: the construction of speech, in which the unions connecting the sentence are omitted. Gives the statement swiftness, dynamism, helps to convey a quick change of pictures, impressions, actions.

Flashing past the booths, women,

Boys, shops, lights,

Palaces, gardens, monasteries,

Bukharians, sleighs, vegetable gardens,

Merchants, shacks, men,

Boulevards, towers, Cossacks,

Pharmacies, fashion stores,

Balconies, lions at the gate

And flocks of jackdaws on the cross.- A. S. Pushkin. Eugene Onegin. Chapter 7

Night, street, lantern, pharmacy,

Senseless and dim light.- A. Block. Night, street, lantern, pharmacy

Hyperbaton (from the ancient Greek. Ὑπέρβατον, literally “permutation”) is a figure of speech in which the theme of the utterance is highlighted by putting it at the beginning or end of a phrase; it may also break the syntactic connection. In other words, hyperbaton is the separation of adjacent words. Along with the anaphor, hyperbaton refers to the figures of displacement (inversion).

Hyperbaton is used mainly to enhance the expressiveness of speech. Hyperbaton is a rather sophisticated figure leaving an impression of pretentiousness, and therefore it is rarely used in colloquial speech. However, this figure is often used in poetry, or analytical and other scientific documents to highlight the meaning [1] :

Firmly the heart of the poor let tears despise.

- A. D. Cantemir. Satire I. On Cheating Teachings

And the god of abuse by grace

Our every step is captured.- A. S. Pushkin. Poltava

Days of the bull peg.

Slow years arba.- V. V. Mayakovsky. Our march

Another famous example of the use of hyperbaton is Master Yoda’s speech in George Lucas’s Star Wars cinematographic saga.

Distinction (from the Latin. Distinctio "distinction") is a figure of speech (trope; a stylistic figure of length [1] ), which denotes an act of knowledge, reflecting an objective difference between real objects and elements of consciousness ("Who does not have anything nicer in life than he cannot lead a decent lifestyle ”).

In formal logic, distinction is one of the logical techniques that can be used instead of the definition [2] .

Zevgma (ancient-Greek. Ζεῦγμα "Zevgema", literally "connection", "connection") is a figure of speech, consisting in the fact that the word that in the sentence forms syntactic combinations of the same type with other words is used only in one of these combinations, in others it falls ( Pochten a nobleman behind the bars of his tower, a merchant - in his shop (Pushkin, “Scenes from chivalrous times”) - the word is honored here is used only once, the second time is implied). In traditional antique rhetoric, Zevgma was not associated with the notion of violation of logical and semantic connections, but in modern rhetoric it is often assumed that Zevgma is based on violation of the law of logical identity ( It was raining and the Red Army detachment . Today in the Kremlin, the President accepted a representative of the OSCE and military doctrine ) . Such an idea of the zeugma as a stylistic mistake goes back to the writings of Adolf Knokh. Depending on the position of the “common,” the words distinguish between protozoevma (the common word at the beginning), mesozevma (the common word in the middle), and hypoevgue (the common word at the end).

The nominative theme (nominative representations, a segment) is a figure of speech, in the first place of which stands an isolated noun in the nominal case, calling the subject of the next phrase. Its function is to arouse particular interest in the subject of the utterance and enhance its sound:

The first part of the nominative theme may include:

• the word;

• word combination;

• several sentences.

“A teacher and a student ... Remember that Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky wrote in his portrait, presented to the young Alexander Pushkin:“ To the winner-student from the defeated teacher. ” The pupil must certainly surpass his teacher, this is the teacher’s highest merit, his continuation, his joy, his right, even if illusory, to immortality ... ”(Mikhail Dudin).

In this example, the nominal construction “Teacher and student ...” is the name of the topic of further reasoning. These words are the key words of the text and determine not only the theme of the utterance, but also the main idea of the text itself.

Thus, similar constructions preceding the text are called nominative representations, or nominative themes. The logical stress falls on the nominative representation (theme), and in speech such constructions are distinguished by a special intonation. This speech figure, undoubtedly, makes the statement expressive.

The nominative theme (presentation) as a syntactic construct, isolated from a sentence, the theme of which it represents, is separated by such punctuation marks that correspond to the end of the sentence: a dot, exclamation point or question mark, ellipsis.

Each punctuation mark introduces a corresponding intonational and semantic tone:

Most often, ellipsis are used (to underline the moment of meditation, pause) and exclamation mark (expresses expressiveness), the combination of exclamation mark and ellipsis is also often used.

This term has other meanings, see Invert.

Inversion is a philological term referring to figures of speech, derived from the Latin word inversio - turning, rearranging - changing the direct order of words or phrases as a stylistic device. There is another type of inversion - hyperbaton. Often regarded as a kind of transformation. Often forms of inversion that are not accepted in ordinary speech are used in poetry:

Minute Life Impressions

My soul shall not save ...

Mesarchy - the figure of speech: the repetition of the same word or words at the beginning and in the middle of the following sentences. As a rule, it is used to create a feeling of monotony of the text and at the same time enhances the hypnotic effect.

Example:

In one black forest

It is a black prechorny house

In this black luxury home

It is a black-fine table ...- Folk horror story

Multiple Union (also polysindeton , from ancient Greek πολυσύνδετον “multi-union”) is a stylistic figure consisting in intentionally increasing the number of alliances in a sentence, usually for the connection of homogeneous members. Slowing down the speech by forced pauses, the multi-union emphasizes the role of each of the words, creating unity of enumeration and strengthening the expressiveness of speech.

Before the eyes, the ocean walked, and swayed, and thundered, and sparkled, and died away, and glowed, and went somewhere to infinity.

- Korolenko V.G.

I either weep, or scream, or faint

- Chekhov A.P.

And the waves are crowded, and rush back,

And they come again and hit the shore ...- Lermontov M. Yu. Ballad

But both grandson, and great-grandson, and great-great-grandson

Growing in me while I myself grow ...- Antokolsky P.G.

Oxymoron , Oxymoron (ancient Greek οξύμωρον, lit. - witty-stupid) - stylistic figure or stylistic mistake - a combination of words with opposite meaning (that is, a combination of incompatible). Oxymoron is characterized by deliberately using controversy to create a stylistic effect. From a psychological point of view, an oxymoron is a way to resolve an unexplainable situation [1] [2] .

And the day has come. Rises from his bed

Mazepa, this sick man is sickly,

This dead body is alive yesterday

Moaning faintly over the grave.- A. S. Pushkin. Poltava

Who should I call? Who do i share

That sad joy that I survived?- Sergey Yesenin. "Soviet Russia"

One should distinguish between oxymorons and stylistic combinations of words that characterize different qualities: for example, the phrase “sweet bitterness” is an oxymoron, and “poisonous honey”, “found loss”, “sweet agony” - stylistic combinations.

This term has other meanings, see Concurrency.

Parallelism (ancient Greek παραλληλισμος - location nearby, juxtaposition) is a rhetorical figure representing the location of identical or similar in grammatical and semantic structure of speech elements in adjacent parts of the text. Parallel elements can be sentences, their parts, phrases, words. For example:

Will I see your bright eyes?

Will I hear a gentle conversation?- Pushkin A.S. Ruslan and Lyudmila

Your mind is deep, that the sea,

Your spirit is high that mountains- Bryusov V. Chinese poems

Parallelism is widespread in folklore and ancient literature literature. In many ancient systems of versification, he acted as the principle of constructing a stanza.

A special kind of parallelism (Latin parallelismus membrorum ) of Hebrew (biblical) versification is known, in which parallelism itself is connected with synonymy, which gives the variation of similar images. For example:

Put me like a seal on your heart like a ring on your hand

- Song. 8: 6

In ancient Germanic verse of the Middle Ages, parallelism is of great importance and is connected with alliteration, as well as rhyme.

Parallelism is widely used in Finnish folklore verse, in particular the Finnish epic Kalevala, where it is combined with the obligatory gradation:

Six he finds seeds

He raises seven seeds.

Parallelism is associated with the structure of the choral action - amoebae composition. Folklore forms of parallelism are widely used in the artistic (literary) song (it. Kunstlied ).

In Russian folklore, the term "parallelism" was used not only to refer to parallelism in the generally accepted sense, but also more narrowly. This term meant “a peculiarity of the poetic composition, which consists in comparing one action (main) with others (minor), observed in the external human world” [1] .

The simplest type of parallelism in Russian folklore is two - term :

The falcon flew across the sky

He walked around the world.

It is assumed that more complex types have evolved from binomial concurrency. Polynomial concurrency consists of several successive parallels. Negative parallelism is one in which the parallel taken from the external world is opposed to the action of a person, as if denies it:

Not a white birch tree bows to the ground -

The Red Maiden bows to the priest.

In formal parallelism, there is no (or lost) logical connection between the comparison of the external world and human actions:

I will lower the little ring into the river,

And the glove under the ice,

We signed up in the commune,

Let all the people judge.

Later written literatures borrow parallelism from folklore and ancient written literatures. In particular, the development of parallelism is characteristic of ancient literature. Under the influence of this parallelism is thoroughly investigated in ancient rhetoric.

In European fiction, parallelism becomes more complex: its connection with an anaphora, antithesis, chiasm and other figures is widely spread.

An example of parallelism with an anaphor and antithesis: “I am a king - I am a slave - I am a worm - I am God!” (Derzhavin. God).

Often in the literature reproduced forms of folklore:

In the blue sky the stars shine,

In the blue sea the waves whip;

A cloud goes across the sky

Barrel on the sea floats.- Pushkin A.S. The Tale of Tsar Saltan

Paronomazia , paronomasia or anomnation (from the ancient Greek Such transcendental words are paronyms. Paronyms - consonant words with different roots, different in meaning. For example: it is pleasant to caress a dog, but it is even more pleasant to rinse your mouth. For example, the Russian “husband for firewood, the wife from the yard,” the French “apprendre n'est pas comprendre” - “to learn is not to understand.”

If the confusion between paronyms is a gross lexical error, the deliberate use of two paronymous words in one sentence is a stylistic figure, which is called paronomasia .

Paromasia is called a binary figure of stylistics, since both paronyms take part in it. This figure is widely distributed, and in abbreviated form it can be called binary.

Paronomasia is widely used as a rhetorical device in ancient Chinese literature. It is correlated with the principle of hieroglyphic word transfer: an expanding and modifying lexicon dictated variations in the use of available graphic signs. The subsequent standardization of hieroglyphics supplanted many examples of paronomasia from pre-imperial texts (see Chinese letter).

The analysis of paronomasia in the ancient Chinese language is a difficult problem, since it is not always clear whether it is a question of artistic pun or language standard (道 - way / speak ; 樂 - music / joy ). Variability in hieroglyphic transmission exacerbates the complexity of the analysis ( joy樂 yuè can be written as 悦 yuè; interchangeable, eg 是 / 氏, 魚 / 吾): it is often difficult to distinguish whether lexical paronomasia is meant or just graphic variability in the transmission of the same words (eg 冬winter / 終demise, death ). The reason for such an extraordinary prevalence of paronomasia was the mono-syllabism of the ancient Chinese language.

In addition to the well-known opening phrase from “Dao de Ching” (道 可 道 , 非常 道。 名 可 名 , , 非常 名。 [1] ), the classic example of parmonasia is the statement of Confucius 觚 不 觚 , 觚 哉! 觚 哉! (Lun yu, 6.25). Its interpretation remains controversial, since 觚 gū means both a vessel for wine and a “corner” [2] .

This term has other meanings, see Parcellation.

Parceling is a construction of expressive syntax, which is the deliberate dismemberment of a text intonation and writing text into several punctuation-independent segments (in the terminology of Swiss linguist Charles Bally, dislocation), for example: “Jeans, tweed jacket and a good shirt. Very good. My lovely! White Plain white shirt. But darling. I put it on ... and went to meet Max ”(Evgeny Grishkovets).

An indicator of the syntactic gap is the point (or another sign of the end of a sentence), which leads to an increase in the frequency of use of the point, and in case of visual perception of the text - to its intonation.

The parcel construction has a two-member structure - the base part and the parcel.

A parcel is a part of a construct that is formed as a result of the dismemberment of a simple or complex sentence and depends (grammatically and

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 Rhetorical figures. Speech figures.

Часть 2 Parcel Examples - Rhetorical figures. Speech figures.

Часть 3 Using - Rhetorical figures. Speech figures.

Comments

To leave a comment

Rhetoric

Terms: Rhetoric