Lecture

Communication is an extremely complex and capacious concept. Often it is interpreted as the interaction of two or more people in order to establish and maintain interpersonal relations, to achieve the overall result of joint activities. From the position of the domestic activity approach, communication is a complex, multi-faceted process of establishing and developing contacts between people, generated by the need for joint activities and includes the exchange of information, the development of a unified interaction strategy, the perception and understanding of another person (Psychology ..., 1996. S. 224) (http://www.psy.msu.ru/about/lab/semantec.html).

Communication is an extremely complex and capacious concept. Often it is interpreted as the interaction of two or more people in order to establish and maintain interpersonal relations, to achieve the overall result of joint activities. From the position of the domestic activity approach, communication is a complex, multi-faceted process of establishing and developing contacts between people, generated by the need for joint activities and includes the exchange of information, the development of a unified interaction strategy, the perception and understanding of another person (Psychology ..., 1996. S. 224) (http://www.psy.msu.ru/about/lab/semantec.html).

Human communication can be viewed not only as an act of conscious, rationally shaped speech communication, but also as a direct emotional contact between people. It is diverse both in content and in the form of manifestation. Communication can vary from high levels of spiritual interpenetration of partners to the most curtailed and fragmented contacts (Stankin MI, 2000; see annotation).

Communication is quite a multifaceted phenomenon (Fig. 1). It represents the attitude of people to each other, and their interaction, and the exchange of information between them, their spiritual interpenetration. The aspect of personality is only one of the components, one of the facets of this phenomenon.

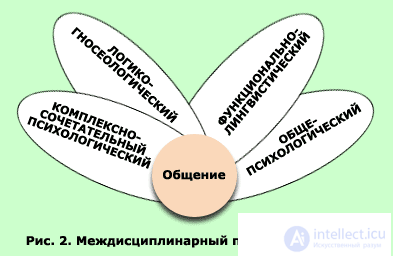

Communication is the subject of study of many sciences (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). For convenience of analysis, N.P. Erastov singles out the logical-gnoseological, functional-linguistic, complex-combined and general psychological approaches to communication as independent (Erastov NP, 1979).

In the logical-epistemological terms, communication is considered as a special kind of cognitive-practical activity of people, aimed at an adequate reflection of reality, carried out in certain conditions with certain goals and with the help of certain means. This approach to communication allows you to specify its social essence to the level of structural components and their relationships with each other in a very general way.

The process of communication can not occur without any means. The analysis of the conformity of these means to the content, setting, goals and partners of communication in many respects contributes to the understanding of its essence and mechanisms. It is clear that the psychological analysis of communication is impossible without a careful study of the specific means and methods of transmitting thoughts, feelings, and intentions of people in real acts of communication.

The main means of communication is language. Therefore, the study of its content, forms, types, capabilities and norms is the most important problem of the theory of communication as such. These aspects of communication are the subject of his study in the functional-linguistic approach to communication.

Actually, the psychological analysis of communication begins where psychological research methods are used, and the observed facts are recorded in terms of psychology as a science and are considered in comparison with already known psychological laws. Communication for the psychologist is, first of all, the patterns of the flow of mental activity of people who communicate with each other with specific goals in certain conditions of his activity.

In the practice of scientific analysis, various variants of combinations of the actual psychological approach to communication with approaches to it from other sciences (sociology, philosophy, physiology, medicine, pedagogy, etc.) have become widespread. Complex-combination approaches form a single alloy, or complex, of psychological and non-psychological information (socio-psychological and psycholinguistic theory of communication), others remain common combinations (psycho-physiological and medical-psychological theory of communication).

Many of the integrated approaches to communication are developed within the framework of traditional applied branches of psychology (social psychology, educational psychology, labor psychology, judicial psychology, pathopsychology, zoopsychology, etc.). Some of the approaches are of a relatively independent nature (psycholinguistic, logical-psychological, psycho-physiological analysis of communication).

Each of these approaches has its own specifics, its own problems. But in general, these problems are based on the general psychological analysis of communication as a phenomenon of mental activity.

Pedagogical communication is a specific interpersonal interaction between a teacher and a pupil (student), mediating the mastering of knowledge and the formation of a personality in the educational process (Pedagogical ..., 1993-1996. Vol. 2). Frequently, pedagogical communication is defined in psychology as the interaction of subjects of the pedagogical process, carried out by symbolic means and aimed at significant changes in the properties, states, behavior, and personal-semantic formations of partners. Communication is an integral element of pedagogical activity; outside it is impossible to achieve the goals of training and education (Leontiev AA, 1996) (http://www.avpu.ru/proect/sbornik2004/161.htm).

In the psychological and pedagogical literature there are different interpretations of pedagogical communication (Fig. 4). We give some of them. For example, A.N. Leontiev defines pedagogical communication as “professional communication of a teacher with students in the classroom and outside of it (in the process of teaching and upbringing), having certain pedagogical functions and directed (if it is complete and optimal) to creating a favorable psychological climate, as well as to a different kind of psychological optimization educational activities and relations between the teacher and the student within the student team "(Leontyev AN, 1979, p. 3). I.A. Winter draws attention to the fact that pedagogical communication "as a form of educational cooperation is a condition for optimizing the learning and development of the personality of the students themselves."

In the psychological and pedagogical literature there are different interpretations of pedagogical communication (Fig. 4). We give some of them. For example, A.N. Leontiev defines pedagogical communication as “professional communication of a teacher with students in the classroom and outside of it (in the process of teaching and upbringing), having certain pedagogical functions and directed (if it is complete and optimal) to creating a favorable psychological climate, as well as to a different kind of psychological optimization educational activities and relations between the teacher and the student within the student team "(Leontyev AN, 1979, p. 3). I.A. Winter draws attention to the fact that pedagogical communication "as a form of educational cooperation is a condition for optimizing the learning and development of the personality of the students themselves."

Pedagogical communication is the main form of the pedagogical process. Its productivity is determined, first of all, by the goals and values of communication, which must be accepted by all subjects of the pedagogical process as an imperative of their individual behavior. You can select the appropriate levels of pedagogical communication (Fig. 5).

The main purpose of pedagogical communication is to transfer social and professional experience (knowledge, skills) from a teacher to students, and to exchange personal meanings related to the objects being studied and life in general (Fig. 6). In communication, the formation (i.e., the emergence of new properties and qualities) of the individuality of both students and teachers occurs (Cialdini R., 2001; see annotation).

Pedagogical communication creates conditions for the realization of the potential essential forces of the subjects of the pedagogical process.

The highest value of pedagogical communication is the individuality of the teacher and the student. Dignity and honor of the teacher, dignity and honor of students is the most important value of pedagogical communication.

In this regard, the leading principle of pedagogical communication can be taken I. Kant's imperative: always treat yourself and the students as the goal of communication, as a result of which there is an ascent to the individuality. The imperative is an absolute requirement. It is this ascent to the individuality in the process of communication that is the expression of the honor and dignity of the subjects of communication.

Pedagogical communication should be guided not only by human dignity as the most important value of communication. Such ethical values as honesty, frankness, unselfishness, trust, mercy, gratitude, care, loyalty to the word are of great importance for productive communication.

The specificity of pedagogical communication, above all, is manifested in its focus. It is aimed not only at the interaction itself and at students for the purposes of their personal development, but also, which is fundamental for the pedagogical system itself, at organizing the learning of learning knowledge and developing skills on this basis. Because of this, pedagogical communication is characterized by a triple focus, as it were, on the learning interaction itself, on students (their current state, promising lines of development) and on the subject of mastering (learning) (Ershov PM, 1998; see annotation).

The specificity of pedagogical communication, above all, is manifested in its focus. It is aimed not only at the interaction itself and at students for the purposes of their personal development, but also, which is fundamental for the pedagogical system itself, at organizing the learning of learning knowledge and developing skills on this basis. Because of this, pedagogical communication is characterized by a triple focus, as it were, on the learning interaction itself, on students (their current state, promising lines of development) and on the subject of mastering (learning) (Ershov PM, 1998; see annotation).

At the same time, pedagogical communication is also determined by a triple focus on the subjects: personal, social and subject. This is due to the fact that the teacher, working with one student on the development of any educational material, always orients its result to everyone in the class, ie frontally affects each learner. Therefore, we can assume that the peculiarity of pedagogical communication, being revealed in the totality of these characteristics, is also expressed in the fact that it organically combines elements of personality-oriented, socially oriented and subject-oriented communication (Mitina LM, 1996; see annotation).

The quality of pedagogical communication is determined primarily by the fact that it implements a specific teaching function, which includes educative. After all, the starting point for organizing an optimal educational process is the educative and developing nature of learning. The training function can be correlated with the translational function of communication, according to A.A. Brudnomu, but only in general terms. The teaching function of pedagogical communication is the leading one, but it is not self-sufficient, it is a natural part of the multilateral interaction of the teacher - the students, the students with each other.

Pedagogical communication reflects the specific character of the interaction of people described by the “person-to-person” scheme (according to EA Klimov).

Pedagogical communication reflects the specific character of the interaction of people described by the “person-to-person” scheme (according to EA Klimov).

Communication is a process of development and formation of relations between the subjects who actively participate in the dialogue. The teacher's speech is the main means that allows him to involve students in his ways of thinking.

As a result of this model of communication, a detrimental effect on the child’s personality occurs. An alternative to this model is the personality-oriented model of communication (see below).

Traditionally, training and upbringing were considered as one-sided processes, the mechanism of which was the transmission of educational information from its carrier - teacher to receiver - student. The pedagogical process, built on the basis of such ideas, in modern conditions demonstrates low efficiency. The student as a passive participant in this process is only able to assimilate (in fact, remember) the limited information that is provided to him in a ready-made form. He does not form the ability to independently master new information, to use it in non-standard conditions and combinations, to find new data on the basis of already learned. One-sided educational process practically does not reach the main goal of education - becoming a mature, independent, responsible person, capable of taking adequate steps in the contradictory and changing conditions of the modern world. The personality under the influence of authoritarian directive influence acquires the features of dependence, conformity (Antsupov A.Ya., 1996).

2. Person-oriented model of communication. The goal of the personality-oriented model of communication is to provide the child’s psychological defenses, confidence in the world, the joy of existence, the formation of the beginning of the personality, the development of the child’s individuality. For this model of communication, the dialogical type of communication is typical (Fig. 8) (Pavlova LG, 1991; see annotation).

2. Person-oriented model of communication. The goal of the personality-oriented model of communication is to provide the child’s psychological defenses, confidence in the world, the joy of existence, the formation of the beginning of the personality, the development of the child’s individuality. For this model of communication, the dialogical type of communication is typical (Fig. 8) (Pavlova LG, 1991; see annotation).

This model of communication is characterized by the fact that an adult interacts with a child in the process of communication (Sinagina N.Yu. et al., 2001; see annotation). It does not drive the development of children, but prevents the occurrence of possible deviations in the personal development of children. The formation of knowledge and skills is not the goal, but the means of the full development of the personality.

In this regard, in modern science and practice, the concept of the pedagogical process as a dialogue, providing for the mutually directed and thus conditional interaction of participants in this process, as well as methods of group discussion (Fig. 9, animation), is becoming increasingly recognized. (Kurganov S.Yu., 1989; see annotation). In this regard, pedagogical communication acts as the main mechanism for achieving the main goals of training and education.

In this regard, in modern science and practice, the concept of the pedagogical process as a dialogue, providing for the mutually directed and thus conditional interaction of participants in this process, as well as methods of group discussion (Fig. 9, animation), is becoming increasingly recognized. (Kurganov S.Yu., 1989; see annotation). In this regard, pedagogical communication acts as the main mechanism for achieving the main goals of training and education.

(http://www.voppsy.ru/journals_all/issues/1995/952/952031.htm; see the article by Yakimanskaya, IS, "Developing a Technology for Personality-Oriented Learning").

Each of these components in the pedagogical process and pedagogical communication acquires its own characteristics.

The perceptive component of pedagogical communication is mediated by the peculiarities of the roles of the participants in the dialogue. В педагогическом процессе осуществляется формирование личности учащегося, которое проходит ряд последовательных этапов, предшествующих оформлению зрелого сознания и мировоззрения. На ранних этапах этого процесса педагог обладает рядом изначальных преимуществ, т.к. он является носителем сформировавшейся личности, а также обладает сложившимися представлениями о целях и механизмах формирования личности воспитанников. Особенности личности педагога, его индивидуально-психологические и профессиональные качества выступают важным условием, определяющим характер диалога. К необходимым профессиональным качествам педагога относится его умение отмечать и адекватно оценивать индивидуальные особенности детей, их интересы, склонности, настроения. Лишь выстраиваемый с учётом этих особенностей педагогический процесс может быть эффективным.

The perceptive component of pedagogical communication is mediated by the peculiarities of the roles of the participants in the dialogue. В педагогическом процессе осуществляется формирование личности учащегося, которое проходит ряд последовательных этапов, предшествующих оформлению зрелого сознания и мировоззрения. На ранних этапах этого процесса педагог обладает рядом изначальных преимуществ, т.к. он является носителем сформировавшейся личности, а также обладает сложившимися представлениями о целях и механизмах формирования личности воспитанников. Особенности личности педагога, его индивидуально-психологические и профессиональные качества выступают важным условием, определяющим характер диалога. К необходимым профессиональным качествам педагога относится его умение отмечать и адекватно оценивать индивидуальные особенности детей, их интересы, склонности, настроения. Лишь выстраиваемый с учётом этих особенностей педагогический процесс может быть эффективным.

Communicative component педагогического общения также во многом обусловлен характером взаимоотношения ролей участников диалога. На ранних этапах педагогического взаимодействия ребёнок ещё не обладает необходимым потенциалом равноправного участника обмена информацией, т.к. не имеет достаточных для этого знаний. Педагог выступает носителем человеческого опыта, который воплощён в заложенных в образовательную программу знаниях. Это, однако, не означает, что педагогическая коммуникация даже на ранних этапах является односторонним процессом. В современных условиях оказывается недостаточным простое сообщение ученикам информации. Необходимо активизировать их собственные усилия по усвоению знаний. Особую важность при этом приобретают т.н. активные методы обучения, стимулирующие самостоятельное нахождение учащимися необходимой информации и её последующее использование применительно к разнообразным условиям. По мере овладения всё большим массивом данных и формирования способности оперировать ими, учащийся становится равноправным участником учебного диалога, вносящим значительный вклад в коммуникативный обмен.

Рассмотрим стереотипизацию подробнее. Под влиянием окружающих и в силу взаимодействия с ними у каждого человека образуются более или менее конкретные эталоны-стереотипы, пользуясь которыми он дает оценку другим людям. Чаще всего формирование устойчивых эталонов протекает незаметно для самого человека, и они приобретают власть над ним именно в силу их недостаточной осознанности.

Чаще всего эти эталоны-стереотипы срабатывают в условиях дефицита информации о человеке, когда о нем вынуждены судить по первому впечатлению.

1. Антропологические стереотипы проявляются в том, что оценка внутренних, психологических качеств человека, оценка его личности зависит от особенностей его физического облика.

2. Этнонацнональные стереотипы проявляются в том случае, если психологическая оценка человека опосредована его принадлежностью к той или иной расе, нации, этнической группе (например, "немец-педант", "темпераментный южанин" и т.п.).

3. Социально-статусные стереотипы состоят в зависимости оценки личностных качеств человека от его социального статуса (в экспериментах выяснилось, что даже рост незнакомого человека оценивается по-разному, в зависимости от того, кем по статусу он является: чем более высоким был социальный статус, тем более высокого роста казался человек).

4. Социально-ролевые стереотипы проявляются в зависимости оценки личностных качеств человека от его социальной роли, ролевых функций (например, стереотип военного как дисциплинированного, жесткого, ограниченного человека, стереотип профессора как умного, рассеянного и т.п.).

5. Экспрессивно-эстетические стереотипы определяются зависимостью оценки личности от внешней привлекательности человека ("эффект красоты": чем более привлекательной кажется внешность оцениваемого, тем более позитивными личностными качествами он наделяется).

6. Вербально-поведенческие стереотипы связаны с зависимостью оценки личности от внешних особенностей (экспрессивные особенности, особенности речи, мимики, пантомимики и т.п.).

В процессе познания педагогом личности учащегося механизм "стереотипизации" действует во всех направлениях: "работают" и социальные, стереотипы, и эмоционально-эстетические, и антропологические и пр. У педагога под влиянием своего педагогического опыта складываются специфические социальные стереотипы: "отличник", "двоечник". Так, впервые встречаясь с учащимся, уже получившим характеристику "отличника" или "двоечника", педагог с большей или меньшей вероятностью предполагает наличие у него определенных качеств. Среди преподавателей чрезвычайно распространен стереотип о связи хорошей успеваемости учащегося с характеристиками его личности: успешно учится - значит, способный, добросовестный, честный, дисциплинированный; успевает плохо - значит, бесталанный, ленивый, несобранный и т.п. Распространен и такой стереотип у педагогов, что "неблагополучными" детьми, склонными к асоциальному поведению, чаще всего являются "ершистые", беспокойные учащиеся, те, которые не могут усидеть на занятиях, не могут молча, подчиненно реагировать на замечания, способны вступить в пререкания. А учащиеся, демонстрирующие подчиненность, действующие в зависимости от указаний и замечаний педагога, оцениваются польщенным педагогом как "благополучные".

В процессе познания педагогом личности учащегося механизм "стереотипизации" действует во всех направлениях: "работают" и социальные, стереотипы, и эмоционально-эстетические, и антропологические и пр. У педагога под влиянием своего педагогического опыта складываются специфические социальные стереотипы: "отличник", "двоечник". Так, впервые встречаясь с учащимся, уже получившим характеристику "отличника" или "двоечника", педагог с большей или меньшей вероятностью предполагает наличие у него определенных качеств. Среди преподавателей чрезвычайно распространен стереотип о связи хорошей успеваемости учащегося с характеристиками его личности: успешно учится - значит, способный, добросовестный, честный, дисциплинированный; успевает плохо - значит, бесталанный, ленивый, несобранный и т.п. Распространен и такой стереотип у педагогов, что "неблагополучными" детьми, склонными к асоциальному поведению, чаще всего являются "ершистые", беспокойные учащиеся, те, которые не могут усидеть на занятиях, не могут молча, подчиненно реагировать на замечания, способны вступить в пререкания. А учащиеся, демонстрирующие подчиненность, действующие в зависимости от указаний и замечаний педагога, оцениваются польщенным педагогом как "благополучные".

Эмоционально-эстетические стереотипы также могут играть определенную роль в процессе педагогического общения: оценивая свое отношение к незнакомым ученикам (по их фото) и их поступкам (описание неблаговидных поступков), педагоги оказались более снисходительными к тем, у кого была более привлекательная внешность (Бодалев А.А., 1995; см. аннотацию).

In the process of communication between the teacher and the student, the task is not only and not so much to transfer information as to achieve its adequate understanding by the latter. That is, interpersonal communication as a special problem is the interpretation of the message received from the teacher to the student and vice versa. First, the form and content of the message essentially depend on the personality characteristics of both the teacher and the student, their ideas about each other and the relations between them, the whole situation in which communication takes place. Secondly, the teaching message transmitted by the teacher does not remain unchanged: it is transformed, changes under the influence of the individual-typological characteristics of the student, his attitude to the teacher, the text itself, the communication situation.

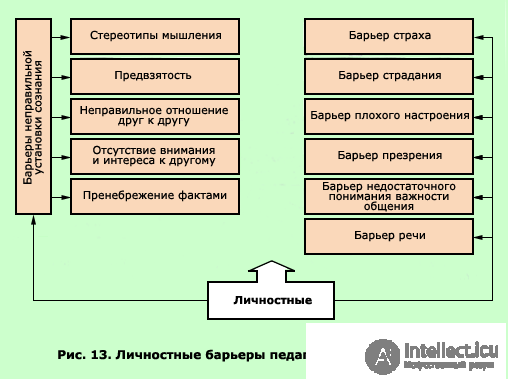

What does the adequacy of perception of educational information depend on? There are a number of reasons, the most important of which is the presence or absence of communication barriers in the process. In the most general sense, the communicative barrier is a psychological obstacle to the adequate transfer of educational information between participants in the pedagogical process . In the event of a barrier, educational information is distorted or loses its original meaning.

Stereotypes represent a stable, simplistic opinion about people (teachers, pupils) and situations. They arise in the pedagogical process in two ways: the meaning of the information may be distorted a) the speaker’s stereotype; b) stereotypical thinking of the perceiver (listener).

Biased perceptions between the teacher and the student result from a decline in self-criticism and a rise in self-esteem (as a rule, not always justified). Bias in pedagogical communication is manifested in the following:

1. False stereotypes related to human perception by external data. (This one is wearing glasses, it means smart, this one is sporty in appearance, it means unintelligent, etc.) Appearance saves pedagogical efforts related to the knowledge of students, but often leads to delusions, which ultimately translate into pedagogical miscalculations.

2. The attribution of advantages or disadvantages to a person based only on his social status. In this case, the student or student is not in the best position: their social status is lower than the status of the teacher.

3. Subjectivism, stamps, stencils, preliminary information that the teacher receives about the student (or other teacher). Following them, the teacher gets on the wrong path of pedagogical communication or is generally out of it. It is necessary to check all information and reassess presets to know the true person, his pros and cons and build communication with him based on the pros, realizing that each person is in something better than the other.

Communication is a set of relationships and mutual influence of people, emerging in their joint activities. It implies some result - a change in the behavior and activities of other people. Each person plays a certain role in society. The multiplicity of role positions often leads to their collision - role conflicts. In some situations, antagonism of positions is revealed, reflecting the existence of mutually exclusive values, tasks, and goals, which sometimes leads to interpersonal conflicts.

Among the indicators of the personal plan, communicative inclinations, abilities, knowledge, skills, communication skills, etc. have the most importance. Certainly, the indicators of the individual-personal plan, such as interests, inclinations, level of preparedness, habits of the teacher and student, affect the performance of pedagogical communication.

In some studies, there is a link between the effective knowledge of the student’s personality and the individual psychological characteristics of the teacher, such as introversion, extroversion, and emotional stability. Studies have shown that, in general, teachers of the introverted type more fully and adequately reflect the student’s personality in comparison with extrovert teachers. Research A.A. Rean found an interesting feature: those teachers who do not associate their professional development with the development of self-confidence (and, conversely, approaching their ideal of professionalism, tend to become less self-confident), give a more positive assessment of the student’s personality. And vice versa, the more a teacher connects his professional self-improvement with an increase in self-confidence, the more often he gives a generally negative assessment of the student’s personality.

You can also identify a number of professionally important qualities of a teacher, necessary to communicate with the audience (Fig. 15).

One of the important qualities of a teacher is the ability to organize long-term and effective interaction with students. This skill is usually associated with the communicative abilities of the teacher. Possession of professional-pedagogical communication is the most important requirement for the personality of the teacher in that aspect, which concerns interpersonal relationships.

First of all, we note that the communicative abilities that are manifested in pedagogical communication are the ability to communicate in a specific way in the field of pedagogical interaction related to the training and education of children . From this you can make at least two useful conclusions:

1. Talking about the ability to pedagogical communication can not be conducted independently of the discussion of general communication skills, manifested in all spheres of human communication.

2. When it comes to the ability to pedagogical communication, it is impossible to limit oneself to talking about general communication skills. Firstly, not all communicative abilities of a person manifest themselves in the same way and are equally necessary for the teacher. Secondly, there are a number of special communication skills that a teacher should possess and which, to a lesser extent, may be necessary for representatives of other professions. In particular, the knowledge of other people, the knowledge of oneself, the correct perception and assessment of situations of communication, the ability to properly behave in relation to people, the actions taken by a person in relation to himself.

The above and other communication skills can be formed at the intuitive, everyday and conscious levels. In addition, in each of them one can distinguish low, medium, and high sublevels (Fig. 17).

The knowledge of a person to a person includes a general assessment of a person as a person, which usually develops on the basis of a first impression of him, an assessment of individual personality traits, motives and intentions, an assessment of the connection of externally observed behavior with the person’s inner world; the ability to "read" poses, gestures, facial expressions, pantomime.

The knowledge of a person himself involves the assessment of their knowledge and their abilities, assessment of their character and other personality traits, assessment of how a person is perceived from the outside and looks in the eyes of others.

The ability to properly assess a communication situation is the ability to observe the situation, select its most informative features and pay attention to them; correctly perceive and evaluate the social and psychological meaning of the situation.

Communicative abilities of a teacher are amenable to development. Good results in their formation gives socio-psychological training.

Pedagogical communication is carried out in various forms, depending mainly on the individual qualities of the teacher and his ideas about his own role in this process. In the psychological-pedagogical literature, this problem is usually considered in connection with the style of educational activities. There are several classifications of pedagogical styles based on different grounds. For example, stand out as opposed to each other regulated and improvisational styles of pedagogical interaction, which can also be considered as styles of pedagogical communication (Shelikhova NI, 1998; see annotation).

The regulated style provides for a strict division and restriction of the roles of participants in the pedagogical process, as well as following certain patterns and rules. Its advantage, as a rule, in the precise organization of educational work. However, this process is characterized by the emergence of new, unexpected conditions and circumstances, which are not provided for by the initial regulation and cannot be tailored to it without conflict. The possibilities of correction of pedagogical interaction in non-standard conditions within the framework of a regulated style are very low.

The improvisational style in this regard has a significant advantage, since allows you to spontaneously find a solution to each, a newly emerging situation. However, the ability to productive improvisation is very individual, so the implementation of the interaction in this style is not always possible. The merits of one style or another are debatable; It seems optimal to combine in the pedagogical process elements of regulation and improvisation, which allows you to simultaneously meet the necessary requirements for the process and the result of training, as well as, if necessary, adjust the mechanisms of interaction.

There is also a traditional division of styles according to the criterion of the role of participants in the pedagogical process. Within the framework of the authoritarian style of communication, these roles are strictly regulated, and the student has an initially subordinate role. It is under this condition that the education and upbringing is carried out as a purposeful impact on the child. Along with these shortcomings, this mechanism is fraught with a gradual lagging behind the increasing abilities of the child, which ultimately leads to a discrepancy between the pedagogical style and the student’s life attitudes.

The extreme opposite of the authoritarian is the style of pedagogical communication, which can be regarded as permissive. Externally, it allows you to achieve relaxed relationships, but is fraught with the possibility of loss of teacher control over the behavior of students.

Optimal is the so-called democratic style of communication, in which there is a certain regulation of the roles of the participants in the dialogue, without prejudice, however, the freedom to manifest individual inclinations and peculiarities of character. It is this style that makes it possible to flexibly adjust the mechanisms of interaction taking into account the increasing role of the student as a participant in an increasingly equal dialogue.

Trying to find out the reasons that make communication one of the strongest factors involved in the formation of personality, it would be a great simplification to see its educational value only in that people entering into communication thus have the opportunity to pass on to each other the knowledge about the reality they possess, as well as the skills and abilities usually required by a person for the successful implementation of subject activities.

The educational value of communication is not only that it broadens the general outlook of a person and contributes to the development of mental formations that are necessary for him to successfully carry out activities of a substantive nature. The educational value of communication is also in the fact that it is a prerequisite for the formation of the general intelligence of a person and, above all, of many of his perceptual, mnemic and mental characteristics.

What requirements do teachers impose on attention, perception, memory, imagination, thinking of students, when they communicate with them everywhere, what tasks they are put before them and what level of activity they bring about - the concrete combination of various characteristics that determine student's intellect (see Chrest. 14.1).

In the psychological and pedagogical literature, such a phenomenon as didactogeny is increasingly being considered today.

Didactics - a negative mental state of the student, caused by a violation of pedagogical tact on the part of the educator (teacher, coach) . It is expressed in frustration, fear, depressed mood, etc. Negatively affects the student's activity, complicates interpersonal relations. The basis of the emergence of didactic is the mental trauma received by the student through the fault of the teacher. This explains the proximity of the symptomatology of didactogeny and neurosis in children, and didactogeny often develops into a neurosis and in this case may require special treatment, in particular methods of psychotherapy (Belukhin DA, 1994; see annotation).

Some teachers consider it acceptable to punish a student or to reduce his high self-esteem to publicly ridicule him, to emphasize (often with exaggeration) his shortcomings, to draw unfavorable comparisons with peer achievements. From the point of view of school mental hygiene, this form of pedagogical communication is extremely harmful, because it gives the external effect of reducing undesirable student activity, but cannot orient to positive achievements in educational activities, etc. Thus, the authority of the teacher is destroyed, the belief in his benevolence and justice, the feeling of his psychological security, which is necessary for the child’s emotional balance, is weakened. To prevent the occurrence of didactics in students, each teacher should strive for maximum tact in communication, educate students taking into account their age and individual psychological (mainly personal) characteristics (Zhuravlev VI, 1995; see annotation),

(http://www.pirao.ru/strukt/lab_gr/l_det_p.html; see the laboratory of the scientific foundations of children's practical psychology).

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 14. PSYCHOLOGY OF PEDAGOGICAL COMMUNICATION

Часть 2 Glossary - 14. PSYCHOLOGY OF PEDAGOGICAL COMMUNICATION

Comments

To leave a comment

Pedagogical psychology

Terms: Pedagogical psychology