Lecture

The problem of motivation and motives of behavior and activity is one of the pivotal in psychology. B.F. Lomov notes that the psychological role of motivation and goal-setting plays a leading role in psychological research (Lomov BF, 1991; abstract) (Fig. 1).

The problem of motivation and motives of behavior and activity is one of the pivotal in psychology. B.F. Lomov notes that the psychological role of motivation and goal-setting plays a leading role in psychological research (Lomov BF, 1991; abstract) (Fig. 1).

It is not surprising that a large number of monographs, both domestic, are devoted to motivation and motives (V.G. Aseev, V.K. Vilyunas, V.I. Kovalev, A.N. Leontyev, M.Sh. Magomed-Eminov, V.S. Merlin, P.V. Simonov, D.N. Uznadze, A.A. Faizullaev, P.M. Yakobson) and foreign authors (J. Atkinson, G. Hall, K. Madsen, A. Maslow, H. Heckhausen and others).

Concepts and theories of motivation, attributable only to man, began to appear in psychological science since the 20s. XX century. The first was the theory of motivation K. Levin (1926). Following it were published the work of representatives of humanistic psychology - A. Maslow, G. Allport, K. Rogers.

In foreign psychology, there are about 50 theories of motivation. In connection with this situation, V.K. Vilyunas (Vilyunas VK, 1990) expressed doubts about the desirability of discussing the issue of what a “motive” is.

In a number of works, the “motive” is considered only as an intellectual product of brain activity. So, J. Godfroy (Godfroy J., 1992) writes that the "motive" is a consideration by which the subject should act. H. Heckhausen (Heckhausen H., 1986; abstract) says even more sharply: this is only a “construct of thinking,” that is, theoretical construction, rather than a real psychological phenomenon. It is not surprising that in his 2-volume monograph the motive is either the need (the need for dominion, which he calls the "power motive"; the need for achievement - the "achievement motive"), or personal dispositions (anxiety, etc.), or external and internal reasons for this or that behavior (assistance, manifestation of aggression).

When looking for the answer to the question: “what are motives?”, You need to remember that this is at the same time the answer to the questions: “why?”, “Why?”, “Why?”, “From which a person behaves this way, but not otherwise"? Most often it happens that what is taken as a motive contributes to answering only one or two of the listed questions, but never to everything.

Nevertheless, most psychologists agree that most often a motive is either an urge, or a goal (object), or an intention, or a need, or a property of a person, or its state.

Motive as a goal (subject) . The prevalence of this point of view is due to the fact that the adoption of a goal (object) as a motive answers the questions “why” and “for what” the action takes place, i.e. explains the purposeful, arbitrary nature of human behavior.

It is the object that gives the purposefulness of the motivations of a person, and the motives themselves - the meaning. This also implies the sense-forming function of the motive (A. N. Leontiev) (Chres. 6.1).

Motive as a need . This point of view on the motive expressed by L.I. Bozovic, A.G. Kovalev, K.K. Platonov, S.L. Rubinstein, gives the answer to the question of "why" is a person's activity, because the need itself contains an active human desire to transform the environment in order to meet the needs. Thus, the source of energy for volitional activity is explained, but it is impossible to get answers to the questions “why” and “why” a person shows this activity.

Motive as a need . This point of view on the motive expressed by L.I. Bozovic, A.G. Kovalev, K.K. Platonov, S.L. Rubinstein, gives the answer to the question of "why" is a person's activity, because the need itself contains an active human desire to transform the environment in order to meet the needs. Thus, the source of energy for volitional activity is explained, but it is impossible to get answers to the questions “why” and “why” a person shows this activity.

Motive as an intention . Knowing the intentions of a person, you can answer the questions: "what does he want to achieve?", "What and how he wants to do?" and thereby understand the basis of behavior. Intentions then act as motives when a person either makes a decision, or when the goal of an activity is remote and its achievement is delayed. The intention is the influence of human needs and intellectual activity associated with an awareness of the means of achieving the goal. That the intention is motive is obvious, but it does not reveal the reasons for the behavior.

Motive as a stable personality trait . This view of the motive is especially characteristic of Western psychologists, who believe that stable personality traits cause human behavior and activity to the same extent as external stimuli. R. Mehley refers to motivational personality traits as anxiety, aggressiveness, level of aspirations, and resistance to frustration. A number of domestic psychologists, in particular K.K. Platonov, M.Sh. Magomed-Eminov, V.S. Merlin

Motive as a motive . The most common and accepted point of view is to understand the motive as an incentive. Since motivation determines not so much physiological, as mental reactions, it is associated with the awareness of the stimulus and giving it some significance. Therefore, most psychologists believe that the motive is not any, but a conscious impulse, reflecting a person's readiness to act or act. Thus, the motivator of motive is a stimulus, and the motivator of an act is an inner conscious motive. In this regard, V.I. Kovalev defines motives as conscious motives of behavior and activity arising from the highest form of reflection of needs, i.e. their awareness. From this definition it follows that the motive is a conscious need. Motivation is seen as a desire to meet the needs (Kovalev, VI, 1988).

An attempt to find a single determinant in determining a motive is a dead-end path, since behavior as a systemic formation is determined by a system of determinants, including at the level of motivation. Therefore, a monistic approach to understanding the essence of the motive does not justify itself, which forces us to replace it with a pluralistic one. For a proper understanding of the psychological content of the motive, it is necessary to use all the psychological phenomena listed above, no matter how cumbersome and indigestible it may be. With this understanding, it is legitimate to consider the motive as a complex integral psychological education.

Consequently, the motive of an individual is both a need, a goal, an intention, an impulse, and a personality trait that determine human behavior

When considering the motivation of a person as a psychological phenomenon, one has to face many difficulties. First of all, there is a terminological ambiguity in the definition of "motivation" and "motive". The situation with the concept itself is no better. As it is called a variety of psychological phenomena: ideas and ideas, feelings and experiences (Bozhovich L.I., 1997; abstract), needs and inclinations, motivations and inclinations (Heckhausen H., 1986; abstract), desires and wants, habits , thoughts and sense of duty (Rudik PA, 1967), moral and political attitudes and thoughts (Kovalev AG, 1969), mental processes, states and personality characteristics (Platonov KK, 1986), external objects peace (Leontyev, AN, 1975), installation (Maslow, A., 1954) and even the conditions of existence (Vilyunas VK, 1990).

When considering the motivation of a person as a psychological phenomenon, one has to face many difficulties. First of all, there is a terminological ambiguity in the definition of "motivation" and "motive". The situation with the concept itself is no better. As it is called a variety of psychological phenomena: ideas and ideas, feelings and experiences (Bozhovich L.I., 1997; abstract), needs and inclinations, motivations and inclinations (Heckhausen H., 1986; abstract), desires and wants, habits , thoughts and sense of duty (Rudik PA, 1967), moral and political attitudes and thoughts (Kovalev AG, 1969), mental processes, states and personality characteristics (Platonov KK, 1986), external objects peace (Leontyev, AN, 1975), installation (Maslow, A., 1954) and even the conditions of existence (Vilyunas VK, 1990).

The point of view that motives are stable characteristics of an individual is mainly characteristic of the work of Western psychologists, but has supporters in our country.

In Western psychology, stable (dispositional) and variable factors of motivation (M. Madsen, 1959), stable and functional variables (H. Murray, 1938), personal and situational determinants (J. Atkinson, 1964) are considered as criteria for the separation of motives and motivation. The authors note that persistent personality characteristics determine behavior and activity to the same extent as external stimuli. Personality dispositions (preferences, inclinations, attitudes, values, worldview, ideals) should take part in the formation of a specific motive.

A number of domestic psychologists (KK Platonov, VS Merlin, M.Sh. Magomed-Eminov) also believe that along with mental states, personality traits can also act as motives.

There is a relationship between motivation and personality traits: personality traits affect the characteristics of motivation, and the traits of motivation, having become entrenched, become personality traits.

In this regard, as notes P.M. Jacobson, it makes sense to raise the question of how much a person is revealed in her motivational sphere. A.N. Leontiev, for example, wrote that the basic structure of the personality is a relatively stable configuration of the main, hierarchical, motivational lines within itself. PM Jacobson, however, rightly observes that far from everything that characterizes a personality affects its motivational sphere (the opposite can also be said: not all features of the process of motivation turn into personality traits). And G. Allport (Allport G., 1938) says the same thing — which would be inaccurate if we say that all motives are traits; Some of the features have a motivational (directing) value, while others are more instrumental.

In this regard, as notes P.M. Jacobson, it makes sense to raise the question of how much a person is revealed in her motivational sphere. A.N. Leontiev, for example, wrote that the basic structure of the personality is a relatively stable configuration of the main, hierarchical, motivational lines within itself. PM Jacobson, however, rightly observes that far from everything that characterizes a personality affects its motivational sphere (the opposite can also be said: not all features of the process of motivation turn into personality traits). And G. Allport (Allport G., 1938) says the same thing — which would be inaccurate if we say that all motives are traits; Some of the features have a motivational (directing) value, while others are more instrumental.

Certainly, traits that have motivational knowledge include such personality characteristics as the level of claims, the desire to achieve success or avoid failure, the motives of affiliation or the motives of rejection (the tendency to communicate with other people, to cooperate with them or, on the contrary, to be afraid unaccepted, rejected), aggressiveness (the tendency to resolve conflicts through the use of aggressive actions).

(http://www.pirao.ru/strukt/lab_gr/l-teor-exp.html; see the laboratory of theoretical and experimental problems of the personality psychology of PI RAO).

The named system of motives forms a learning motivation , which is characterized by both stability and dynamism.

Dominant intrinsic motifs determine the stability of learning motivation, the hierarchy of its main substructures. Social motives determine the constant dynamics of entering into new relationships with each other. A.K. Markova notes that the emergence of motivation "is not a simple increase in the positive or aggravation of the negative attitude to the doctrine, but the complication of the structure of the motivational sphere, its impulses, the emergence of new, more mature, sometimes contradictory relations between them" (Formation ..., 1986 S. 14).

Dominant intrinsic motifs determine the stability of learning motivation, the hierarchy of its main substructures. Social motives determine the constant dynamics of entering into new relationships with each other. A.K. Markova notes that the emergence of motivation "is not a simple increase in the positive or aggravation of the negative attitude to the doctrine, but the complication of the structure of the motivational sphere, its impulses, the emergence of new, more mature, sometimes contradictory relations between them" (Formation ..., 1986 S. 14).

Learning motivation is defined as a private type of motivation that is included in a particular activity — in this case, a teaching activity, a learning activity.

Learning motivation allows a developing person to determine not only the direction, but also the means of implementing various forms of learning activity, to engage the emotional-volitional sphere. It acts as a meaningful multi-factor determination, which determines the specificity of the learning situation in each time interval.

Internal sources of learning motivation include cognitive and social needs (striving for socially approved actions and achievements).

External sources of learning motivation are determined by the conditions of the trainee’s life, which includes requirements, expectations and opportunities. Requirements are associated with the need to comply with social norms of behavior, communication and activities. Expectations characterize the attitude of society to the doctrine as to the norm of behavior that is accepted by a person and makes it possible to overcome the difficulties associated with the implementation of educational activities. Opportunities are objective conditions that are necessary for the deployment of learning activities (availability of schools, textbooks, libraries, etc.).

Personal sources . Among these sources of activity that motivate learning activities, a special place is occupied by personal sources. These include interests, needs, attitudes, standards and stereotypes, and others that determine the desire for self-improvement, self-affirmation and self-realization in educational and other activities.

The interaction of internal, external and personal sources of learning motivation influences the nature of learning activities and its results. The absence of one of the sources leads to the restructuring of the system of educational motives or their deformation.

I. The motives inherent in the training activities:

1) Motives associated with the content of the doctrine: the student is encouraged to learn the desire to learn new facts, to acquire knowledge, methods of action, to penetrate into the essence of phenomena, etc.

2) Motives associated with the learning process itself: the student is motivated to learn the desire to exercise intellectual activity, to reason, to overcome obstacles in the process of solving problems, i.e. the child is fascinated by the decision process itself, and not just the results obtained.

По мнению Марковой А.К. (Маркова А.К., 1990; аннотация), к видам мотивов можно отнести познавательные и социальные мотивы (рис. 2). Если у школьника в ходе учения преобладает направленность на содержание учебного предмета, то можно говорить о наличии познавательных мотивов. Если у ученика выражена направленность на другого человека в ходе учения, то говорят о социальных мотивах.

По мнению Марковой А.К. (Маркова А.К., 1990; аннотация), к видам мотивов можно отнести познавательные и социальные мотивы (рис. 2). Если у школьника в ходе учения преобладает направленность на содержание учебного предмета, то можно говорить о наличии познавательных мотивов. Если у ученика выражена направленность на другого человека в ходе учения, то говорят о социальных мотивах.

К познавательным мотивам относятся такие, как собственное развитие в процессе учения; действие вместе с другими и для других; познание нового, неизвестного.

К социальным — такие мотивы, как понимание необходимости учения для дальнейшей жизни, процесс учения как возможность общения, похвала от значимых лиц. Они являются вполне естественными и полезными в учебном процессе, хотя их уже нельзя отнести полностью к внутренним формам учебной мотивации.

Эти мотивы могут оказывать и заметное негативное влияние на характер и результаты учебного процесса. Наиболее резко выражены внешние моменты в мотивах учебы ради материального вознаграждения и избегания неудач.

Одной из основных задач учителя является повышение в структуре мотивации учащегося удельного веса внутренней мотивации учения.

По мнению Марковой А.К., и познавательные, и социальные мотивы могут иметь разные уровни .

Как указывает А.К. Маркова, разные мотивы имеют неодинаковые проявления в учебном процессе (рис. 3). Например, широкие познавательные мотивы проявляются в принятии решения задач, в обращениях к учителю за дополнительными сведениями; учебно-познавательные - в самостоятельных действиях по поиску решения, в вопросах, задаваемых учителю по поводу разных способов работы; мотивы самообразования обнаруживаются в обращениях к учителю с предложениями рациональной организации учебного процесса, в реальных действиях самообразования.

Широкие социальные мотивы проявляются в поступках, свидетельствующих о понимании учеником своего долга и ответственности; позиционные мотивы - в стремлении к контактам со сверстниками и в получении их оценок, в инициативе и помощи товарищам; мотивы социального сотрудничества - в стремлении к коллективной работе и к осознанию рациональных способов ее осуществления. Осознанные мотивы выражаются в умении школьника рассказать о том, что его побуждает, выстроить мотивы по степени значимости; реально действующие мотивы выражаются в успеваемости и посещаемости, в развернутости учебной деятельности и формах ухода от нее, в выполнений дополнительных заданий или отказе от них, в стремлении к заданиям повышенной или пониженной сложности и т.д.

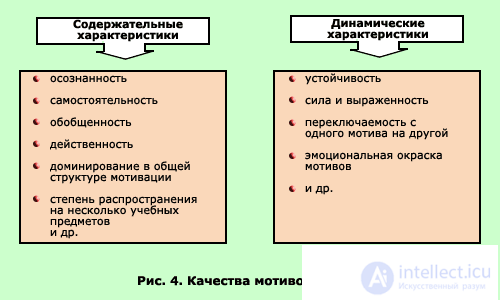

Учебная мотивация характеризуется силой и устойчивостью учебных мотивов (рис. 4).

Сила учебного мотива выступает показателем непреодолимого стремления учащегося и оценивается по степени и глубине осознания потребности и самого мотива, по его интенсивности. Сила мотива обусловлена как физиологическими, так и психологическими факторами. К первым следует отнести силу мотивационного возбуждения, а ко вторым - знание результатов учебно-познавательной деятельности, понимание ее смысла, определенная свобода творчества. Кроме того, сила мотива определяется и эмоциями, что особенно ярко проявляется в детском возрасте.

В свое время Дж. Аткинсон предложил формулу для подсчета силы мотива (стремления): М = П х В х З, где: М - сила мотива, П - мотив достижения успеха как личностное свойство, В - субъективно оцениваемая вероятность достижения поставленной цели, З - личностное значение достижения этой цели.

Устойчивость учебного мотива оценивается по его наличию во всех основных видах учебно-познавательной деятельности учащегося, по сохранению его влияния на поведение в сложных условиях деятельности, по его сохранению во времени. По сути, речь идет об устойчивости (ригидности) установок, ценностных ориентации, намерений учащегося.

Наряду с указанными, выделяют стимулирующую, управляющую, организующую (Е.П. Ильин), структурирующую (О.К. Тихомиров), смыслообразующую (А.Н. Леонтьев), контролирующую (А.В. Запорожец) и защитную (К. Обуховский) функции мотива.

Характеризуя интерес (в общепсихологическом определении - это эмоциональное переживание познавательной потребности) как один из компонентов учебной мотивации, необходимо обратить внимание на то, что в повседневном бытовом, да и в профессиональном педагогическом общении термин "интерес" часто используется как синоним учебной мотивации. Об этом могут свидетельствовать такие высказывания, как "у него нет интереса к учебе", "необходимо развивать познавательный интерес" и т. д. Такое смещение понятий связано, во-первых, с тем, что в теории учения именно интерес был первым объектом изучения в области мотивации (И. Гербарт). Во-вторых, оно объясняется тем, что сам по себе интерес - это сложное неоднородное явление. Интерес определяется "как следствие, как одно из интегральных проявлений сложных процессов мотивационной сферы", и здесь важна дифференциация видов интереса и отношения к учению. Интерес, согласно А.К. Марковой, "может быть широким, планирующим, результативным, процессуально-содержательным, учебно-познавательным и высший уровень - преобразующий интерес" (Формирование…, 1986, С 17-18).

Характеризуя интерес (в общепсихологическом определении - это эмоциональное переживание познавательной потребности) как один из компонентов учебной мотивации, необходимо обратить внимание на то, что в повседневном бытовом, да и в профессиональном педагогическом общении термин "интерес" часто используется как синоним учебной мотивации. Об этом могут свидетельствовать такие высказывания, как "у него нет интереса к учебе", "необходимо развивать познавательный интерес" и т. д. Такое смещение понятий связано, во-первых, с тем, что в теории учения именно интерес был первым объектом изучения в области мотивации (И. Гербарт). Во-вторых, оно объясняется тем, что сам по себе интерес - это сложное неоднородное явление. Интерес определяется "как следствие, как одно из интегральных проявлений сложных процессов мотивационной сферы", и здесь важна дифференциация видов интереса и отношения к учению. Интерес, согласно А.К. Марковой, "может быть широким, планирующим, результативным, процессуально-содержательным, учебно-познавательным и высший уровень - преобразующий интерес" (Формирование…, 1986, С 17-18).

Важность создания условий возникновения интереса к учителю, к учению (как эмоционального переживания удовлетворения познавательной потребности) и формирования самого интереса отмечалась многими исследователями. На основе системного анализа были сформулированы основные факторы, способствующие тому, чтобы учение было интересным для ученика (Бондаренко С.М., 1972. С. 251-252). Согласно данным этого анализа, важнейшей предпосылкой создания интереса к учению является воспитание широких социальных мотивов деятельности, понимание ее смысла, осознание важности изучаемых процессов для собственной деятельности.

Необходимое условие для создания у учащихся интереса к содержанию обучения и к самой учебной деятельности - возможность проявить в учении умственную самостоятельность и инициативность. Чем активнее методы обучения, тем легче вызвать интерес к учению. Основное средство воспитания устойчивого интереса — использование таких вопросов и заданий, решение которых требует от учащихся активной поисковой деятельности.

Большую роль в формировании интереса к учению играет создание проблемной ситуации, столкновение учащихся с трудностью, которую они не могут разрешить при помощи имеющегося у них запаса знаний; сталкиваясь с трудностью, они убеждаются в необходимости получения новых знаний или применения старых в новой ситуации. Интересна только та работа, которая требует постоянного напряжения. Легкий материал, не требующий умственного напряжения, не вызывает интереса. Преодоление трудностей в учебной деятельности - важнейшее условие возникновения интереса к ней. Но трудность учебного материала и учебной задачи приводит к повышению интереса только тогда, когда эта трудность посильна, преодолима, в противном случае интерес быстро падает.

Учебный материал и приемы учебной работы должны быть достаточно (но не чрезмерно) разнообразны. Разнообразие обеспечивается не только столкновением учащихся с различными объектами в ходе обучения, но и тем, что в одном и том же объекте можно открывать новые стороны. Один из приемов возбуждения у учащихся познавательного интереса - "остранение", т. е. показ учащимся нового, неожиданного, важного в привычном и обыденном. Новизна материала - важнейшая предпосылка возникновения интереса к нему. Однако познание нового должно опираться на уже имеющиеся у школьника знания. Использование прежде усвоенных знаний - одно из основных условий появления интереса. Существенный фактор возникновения интереса к учебному материалу - его эмоциональная окраска, живое слово учителя.

Эти положения, сформулированные С.М. Бондаренко, могут служит определенной программой организации учебного процесса, специально направленной на формирование интереса ).

An important element for the analysis of the motivational sphere of the teachings of students is the attitude of the student towards him. Thus, A.K. Markova, defining three types of attitudes toward learning — negative, neutral, and positive — results in a clear differentiation of the latter based on involvement in the learning process (Fig. 5), (Fig. 6). It is very important, she writes, to manage the student’s learning activities: "... a) positive, implicit, active ... meaning the student’s readiness to engage in learning ... b) ... positive, active, cognitive, c) ... positive , active, personal and biased, meaning the involvement of the student as a subject of communication, as a person and a member of society "(Markova AK and others 1990; abstract). In other words, the motivational sphere of the subject of educational activity, or his motivation, is not only multi-component, but also heterogeneous and different levels, which once again convinces the extraordinary complexity not only of its formation, but also of accounting, and even adequate analysis.

Of great importance is the study of such broad forms of motivation, which, manifesting themselves in different areas of activity (professional, scientific, educational), determine the creative, proactive attitude to the work and affect both the nature and quality of the performance of work. One of the main types of such motivation is the achievement motivation, which determines the desire of a person to perform business at a high level of quality wherever there is an opportunity to show their skills and abilities. It is fundamentally important that the achievement motivation is closely related to such personality traits as initiative, responsibility, conscientious attitude to work, realism in assessing one’s abilities when setting goals, etc.

Achievement-oriented behavior implies that every person has a motive for achieving success and avoiding failure. In other words, all people have the ability to be interested in achieving success and worrying about failure. However, each individual has a dominant tendency to be guided either by the motive of achievement, or by the motive of avoiding failure. In principle, the motive of achievement is associated with productive performance of activities, and the motive of avoiding failure is with anxiety and protective behavior.

The predominance of a motivational tendency is always accompanied by the choice of the difficulty of the goal. People motivated to succeed prefer medium-sized or slightly overestimated goals, which only slightly exceed the results already achieved. They prefer to risk prudently. Motivated to fail are prone to extreme elections, some of them are unrealistically underestimated, while others unrealistically overestimate the goals that they set for themselves.

After completing a series of tasks and obtaining information about successes and failures in solving them, those who are motivated to achieve overestimate their failures, and those who are motivated to fail, on the contrary, overestimate their successes.

Motivated to fail in the case of simple and well-developed skills (like those used to add pairs of single-digit numbers) are faster, and their results decrease more slowly than those motivated to succeed. With tasks of a problematic nature that require productive thinking, these same people worsen their work in the conditions of time shortage, and in those who are motivated for success, it improves.

A person's knowledge of his abilities influences his expectations of success. When a class has a full range of abilities, only students with average abilities will be very motivated to achieve and / or avoid failure. Neither the very smart nor the low-performing students will have a strong motivation associated with the achievement, because the situation of competition will seem either "too easy" or "too difficult."

What happens if classes are organized according to the principle of equal level of ability? When schoolchildren with approximately the same abilities will be in the same class, their interest in achieving success and anxiety about their own insolvency will increase. In such classes, students' productivity increases with strong achievement motivation and weak anxiety. It is these students who show an increased interest in learning after transition to homogeneous classes. At the same time, students whose motivation for avoiding failure prevails are less satisfied in an atmosphere of greater competition in a class that is homogenous in ability.

If a person is focused on success, he does not feel the fear of failure, and if he is focused on avoiding failure, he will carefully weigh his possibilities and hesitate when making a decision. Since individuals with a motivation for avoiding failure are afraid of criticism, as a psychological defense, they are more likely than people who are striving for success to motivate their actions with the help of declared morality.

The desire to achieve success according to F. Hoppe (1930), or the “motive of achievement,” according to D. McClelland, is the persistently manifested need of an individual to achieve success in various types of activity. For the first time this disposition (motivational property) was highlighted in the classification of G. Murray. His motivational concept, in which, along with the list of organic or primary needs identical to the basic instincts identified by W. McDougall, Murray offered a list of secondary (psychogenic) needs arising from instinct-like drives as a result of upbringing and training, became quite widely known. These are the needs to achieve success, affiliation, aggression, independence, counteraction, respect, humiliation, protection, domination, attention, avoidance of harmful effects, avoidance of failure, patronage, order, play, rejection, understanding, sexual relations, help, mutual understanding. Later, to these twenty, six more needs were added: acquisitions, dismissal of charges, knowledge, creation, explanation, recognition, and thrift. The disposition we are considering G. Murray understood as a sustainable need to achieve results in work, as a desire to "do something quickly and well, to reach a level in any business." This need is generalized and manifests itself in any situation, regardless of its specific content.

The desire to achieve success according to F. Hoppe (1930), or the “motive of achievement,” according to D. McClelland, is the persistently manifested need of an individual to achieve success in various types of activity. For the first time this disposition (motivational property) was highlighted in the classification of G. Murray. His motivational concept, in which, along with the list of organic or primary needs identical to the basic instincts identified by W. McDougall, Murray offered a list of secondary (psychogenic) needs arising from instinct-like drives as a result of upbringing and training, became quite widely known. These are the needs to achieve success, affiliation, aggression, independence, counteraction, respect, humiliation, protection, domination, attention, avoidance of harmful effects, avoidance of failure, patronage, order, play, rejection, understanding, sexual relations, help, mutual understanding. Later, to these twenty, six more needs were added: acquisitions, dismissal of charges, knowledge, creation, explanation, recognition, and thrift. The disposition we are considering G. Murray understood as a sustainable need to achieve results in work, as a desire to "do something quickly and well, to reach a level in any business." This need is generalized and manifests itself in any situation, regardless of its specific content.

D. McClelland began to study the "achievement motive" in the 40s. Twentieth century. According to the theory of motivation created by him, all, without exception, the motives and needs of a person are acquired, formed during his ontogenetic development. Under it, the motive is understood as “striving to achieve some fairly common target states,” types of satisfaction or results. However, the “achievement motive” is considered not as a derivative of socio-historical conditions, but as the root cause of human behavior. At the same time, it is concluded that the success of the economic development of a society depends on the “national level” of the motive for achieving success. In essence, this is the psychologisation of social phenomena.

D. McClelland began to study the "achievement motive" in the 40s. Twentieth century. According to the theory of motivation created by him, all, without exception, the motives and needs of a person are acquired, formed during his ontogenetic development. Under it, the motive is understood as “striving to achieve some fairly common target states,” types of satisfaction or results. However, the “achievement motive” is considered not as a derivative of socio-historical conditions, but as the root cause of human behavior. At the same time, it is concluded that the success of the economic development of a society depends on the “national level” of the motive for achieving success. In essence, this is the psychologisation of social phenomena.

D. McClelland created the first standardized version of his measurement methodology - Thematic Apperception Test (TAT). At the same time, two types of “achievement motive” were identified: the desire for success and the desire to avoid failure. Later V. Meyer, X. Heckhausen and L. Kemmler (1965) created the TAT version for both "achievement motives" (HeckhausenH., 1986; abstract). The motive of striving for success is understood as a tendency to experience pleasure and pride in achieving a result. The motive for avoiding failure is the tendency to respond by experiencing shame and humiliation to failure.

If McClelland is further interested in primarily the various manifestations of the need to achieve, then J. Atkinson pays more attention to the creation of a theory and a mathematical model to guide empirical research in the field of achievement motivation. The model of choice proposed by Atkinson, in comparison with the model of Escalone, L. Festinger and K. Levin, is more verifiable and more consistent with empirical data. Atkinson believed that the choice is determined by two trends - to achieve success and avoid failure.

The tendency to strive for success is understood as the force that causes the individual to act, which he expects will lead to success. This trend is manifested in the direction, intensity and perseverance of the activity. It is created by the following factors: personal - the motive, or the need to achieve, and two situational - the expectation, or the subjective probability of success, and the motivating value of success.

The tendency to avoid failure is understood as the power that suppresses an individual from performing actions that he expects will lead to failure. The tendency to avoid failure is manifested in the fact that a person seeks to get out of a situation containing the threat of failure. This tendency is created by a personal factor - the motive of avoidance and situational - by expectation, or by the subjective probability of failure.

The motive of avoidance is the individual's general predisposition to avoid failure. It is assumed that the motive is a stable personal characteristic, which is assessed using anxiety questionnaires.

The theory of J. Atkinson suggests that everyone possesses both a motive of achievement and a motive of avoidance. Therefore, in a situation of choice, a person has a conflict between the tendency to strive for success, which causes actions leading to success, and the tendency to avoid failure, which suppresses actions that lead to failure. As in the Escalone, Festinger, and K. Lewin models, it is assumed here that this conflict is resolved algebraically in the form of a resulting trend.

Further improvement of the model J. Atkinson was carried out by Fizer, who introduced the concept of extrinsic motivation. He believes that the general tendency to fulfill a task is the sum of the resulting tendency to strive for success and to avoid failure and external motivation to accomplish the task.

Extrinsic motivation must be viewed in different terms of motives and motivations than those internally associated with achievement and failure. In defense of these provisions, Fizer gives the following arguments. If the achievement motivation would be the only one included in the situation, then it is obvious that a person with a strong avoidance motive would not even have to take on the task. This person should avoid such a task and choose activities that do not cause anxiety about failure. On the contrary, a person with a strong achievement motive should always show a positive interest in completing tasks related to achievement. The concept of external motivation to perform a task is necessary in order to take into account the fact that a person is in a social situation in which he plays the role of the subject in experiments and knows that he is expected to make some effort in carrying out the task. In any experimental situation, there are certain external coercions that affect the subject so that he performs the task regardless of the nature of his motivation associated with the achievement.

According to the theory of the activity origin of the motivational sphere, A.N. Leontiev (60s of the 20th century), in the process of growing up, many of the leading motives of behavior eventually become so characteristic of a person that they turn into personality traits (Leontyev AN, 1975). These include, along with the motive of power, altruism, aggressive motives of behavior and others, the motivation of achievement and the motivation of avoiding failure.

Dominant motifs become one of the main personality characteristics, reflecting on the characteristics of other personality traits.

For example, it was found that people focused on success are more often dominated by realistic ones, and among individuals oriented toward the avoidance of failures, unrealistic, inflated or undervalued, self-evaluations. The level of self-esteem is largely associated with a person’s satisfaction or dissatisfaction with himself, his activity, resulting from the achievement of success or the appearance of failure. The combination of success in life and failure, the predominance of one over the other gradually form the self-esteem of the individual. In turn, the peculiarities of self-esteem of a person are expressed in the goals and general orientation of human activity, since in practice he tends to achieve results that are consistent with his self-esteem and contribute to its strengthening.

The achievement motivation (in the understanding of M.Sh. Magomed-Eminova) is the mental regulation of activity in achievement situations in which there is an opportunity to realize the achievement motive.

The motive of achievement can be realized in different types of activities. This is explained by the fact that the result of activity in itself does not realize the motive of achievement, which is widely generalized by the subject content of personal motive. Personal motives are characterized rather than by the result itself, to which the activity is directed, but by what personality traits are carried out when performing this activity. Activity in its fullness encompasses two poles - the pole of the object and the pole of the subject. At the same time, the pole of the object concerns the objectiveness of activity, the subject pole - of the personality as the "inner moment of activity". Specific motives of activity are associated with an objective pole of activity, and generalized motives of a personality are associated with a subjective pole. However, for the same person, the achievement motive may not be realized in all activities and not equally in those in which it is realized, i.e. for each there is a characteristic circle of activities in which the achievement motive is realized.

The subject content of the motive has a dual structure: functional content, which defines the general area of subject relatedness of the activity of the individual, and specific (or specific content).

Generalized stable motives of the personality are characterized by the generalization of the subject content and are expressed in the individual-personal characteristics. These include, among others, the motive of striving for success and the motive of avoiding failure. Specific stable motives are characterized by systematically reproducible activity aimed at narrow specific areas. Specific unstable motives are characterized by a narrow time perspective, the absence of an extensive system of goals.

Authors of theories look at the ratio of motives for striving for success and avoiding failure in a different way. Some believe (for example, J. Atkinson) that these are mutually exclusive poles on the “achievement motive” scale, and if a person is focused on success, then he does not feel fear of failure (and vice versa, if he is focused on avoiding failure, then he is poorly expressed striving for success). Others argue that a clearly expressed desire for success may well be combined with an equally strong fear of failure, especially if it is associated for the subject with any dire consequences. And, indeed, there is evidence that there can be a positive correlation between the severity of striving for success and avoiding failure. Therefore, it is most likely a question of the predominance of one or another subject of striving for success or avoiding failure in the presence of both. Moreover, this predominance can be both at a high and at a low level of expression of both aspirations.

Subjects motivated to succeed prefer tasks of average or slightly above average difficulty. They are confident in the successful outcome of their plans, they are in search of information for judging their success, decisiveness in uncertain situations, a tendency to reasonable risk, willingness to take responsibility, greater perseverance in striving for a goal, an adequate average level of aspirations, which increases after success and decreases after failure. Very easy tasks do not bring them feelings of satisfaction and real success, and if they choose too difficult, the probability of failure is high; therefore, they choose neither. When choosing the tasks of medium difficulty, success and failure become equally probable and the outcome becomes maximally dependent on the person’s own efforts. In a situation of competition and testing abilities, they are not lost.

Subjects with a tendency to avoid failure seek information about the possibility of failure in achieving a result. Они берутся за решение как очень легких задач (где им гарантирован 100-процентный успех), так и очень трудных (где неудача не воспринимается как личный неуспех). А. Бирни с коллегами (1969) выделяют три типа боязни неудачи и соответствующие им защитные стратегии: боязнь обесценивания себя в собственном мнении, боязнь обесценивания себя в глазах окружающих и боязнь не затрагивающих Я последствий.

Экспериментальное исследование, проведенное М.Ш. Магомед-Эминовым (Магомед-Эминов М.Ш.), показало, что одним из основных механизмов актуализации мотивации достижения выступает мотивационно-эмоциональная оценка ситуации, складывающаяся из оценки мотивационной значимости ситуации и оценки общей компетентности в ситуации достижения; интенсивность мотивационной тенденции меняется в зависимости от изменения величины двух указанных параметров как у испытуемых с мотивом стремления к успеху, так и с мотивом избегания неудачи.

Испытуемые с мотивом достижения при высокой компетентности выбирают трудные задачи, а при низкой компетентности - легкие задачи; испытуемые с мотивом избегания неудачи при высокой компетентности выбирают очень легкие задачи, а при низкой компетентности - очень трудные.

В релаксирующей ситуации, в которой низка мотивационная значимость ситуации, у испытуемых с мотивом избегания неудачи обнаруживается асимметрия выбора цели в сторону трудных задач. В активирующей ситуации, когда мотивационная значимость высокая, зона целей, выбираемых этими испытуемыми, сдвигается, наоборот, в сторону легких задач.

По данным Д. Макклелланда, формирование "мотива достижения" во многом зависит от воспитания ребенка в семье, начиная с раннего детства (соблюдение режима, ориентация ребенка на инициативность и самостоятельность).

Остановимся на возрастном аспекте рассматриваемой нами диспозиции.

В преддошкольном возрасте у детей появляются новые мотивы: мотивы достижения успеха, соревнования, соперничества, избегания неудач. Равнодушие младших дошкольников к удачам и неудачам сменяется у средних дошкольников переживанием успеха и неуспеха (успех вызывает у них усиление мотива, а неуспех - уменьшение его). У старших дошкольников стимулировать может и неуспех.

У детей с высокой успеваемостью ярко выражена мотивация достижения успеха - желание хорошо выполнить задание, сочетающееся с мотивацией получения высокой оценки или одобрения взрослых. У слабоуспевающих школьников начальных классов мотив достижения выражен значительно хуже, а в ряде случаев вообще отсутствует.

Мотив избегания неудач присущ как хорошо успевающим, так неуспевающим учащимся младших классов, но к окончанию начальной школы у последних он достигает значительной силы, поскольку мотив достижения успеха у них практически отсутствует. Почти четверть неуспевающих третьеклассников отрицательно относится к учению из-за того, что у них преобладает мотив избегания неудач (http://psy.1september.ru/2001/02/5_12.htm; см. тест мотивации достижения для детей 9-11 лет. (Н. Афанасьева).

В традиционном обучении часто наблюдается феномен, который видный американский ученый, профессор психологии Пенсильванского университета М. Селигман назвал комплексом " обученной беспомощности ". В чем суть этого явления?

В педагогической практике часто формируется порочный замкнутый круг, когда низкий уровень знаний или неспособность донести свои знания до учителя наказываются плохой оценкой и моральным осуждением. Следовательно, учитель вместо того, чтобы мобилизовать школьника на активную учебу, окончательно его демобилизует и приводит еще к большему отставанию, которое, в свою очередь, влечет за собой неудовлетворительные оценки.

Беспомощность и самооценка . Как показали результаты ряда исследований, эффективность обучения зависит не только от того, что человек убеждается в своей неспособности повлиять на данную ситуацию, решить конкретную задачу, но и от сформировавшихся в его прошлом опыте ожиданий. Так, очень многое определяется тем, считает ли человек данную задачу вообще нерешаемой, или он полагает, что она не по силам только ему. Обученная беспомощность развивается, как правило, только в последнем случае. Более того, человек может даже признать, что задача имеет решение, но оно доступно только лицам, обладающим специальной подготовкой, на которую он не претендует. В принципе, такой внутренней установки достаточно, чтобы неудача в этом, частном случае случае не сказалась на всем дальнейшем поведении. Так, если школьник полагает, что с непосильной для него математической задачей может справиться только учитель математики, приобретенный опыт неудачи не влияет на решение других задач. Если же он полагает, что решение не составляет большого труда для одноклассников и недоступно только ему, то такая позиция может привести не только к плохой успеваемости по математике, но и к отставанию по другим дисциплинам и к неспособности преодолевать жизненные трудности, встречающиеся за пределами обучения.

Тяжелое переживание беспомощности возникает иногда как результат отсутствия педагогического такта у учителей. В наборе ругательных штампов некоторых учителей есть и такие: "ты все равно никогда не научишься", "ты никогда не вылезешь из двоек", "ты больше тройки никогда не будешь иметь" и т.п. При этом они не задумываются над тем, какой вред и учебе, и развитию личности они причиняют.

Сферы беспомощности . Отнесение причин неудач вовне или вовнутрь - не единственная установка, определяющая проявления обученной беспомощности. Человек может считать, что он терпит неудачу только здесь и сейчас. Но он может предполагать, что неудачи будут преследовать его в дальнейшем, причем не только в этой конкретной деятельности, но и в любой другой. При этом отношения между различными установками могут быть сложными. Действительно, отстающий ученик может полагать, что причиной его плохих оценок является отсутствие способностей, низкий уровень интеллекта. В этом случае его беспомощность обусловлена внутренней причиной, стабильна и глобальна. Ведь плохие способности могут определить не только отставание по всем предметам, но и неудачи в будущем. Но он может считать, что его неудачи являются следствием переутомления или нервного истощения. В этом случае его беспомощность, хотя и определяется внутренней причиной и на данный момент распространяется на все виды деятельности, не является стабильной (ибо отдых и укрепление здоровья открывают перспективы улучшения успеваемости). Вместе с тем, причины неуспеваемости могут приписываться внешним обстоятельствам. Тогда беспомощность окажется стабильной и относящейся ко всем изучаемым предметам (если только неудача на экзаменах не объясняется тем, что требования экзаменаторов выходят за рамки школьной программы). Точно такая же установка может касаться какого-то отдельного предмета, и тогда беспомощность будет специфически-локальной и не отразится на результатах других экзаменов. Такой внутренний фактор, как отсутствие интереса к какому-то одному предмету, определит локальную, но постоянную беспомощность в изучении именно этого предмета. Ведь впечатление, что человеку не хватило времени на подготовку к данному экзамену, создает предпосылки для нестабильной и локальной беспомощности, связанной с внешним фактором (дефицит времени).

Все вышеизложенное имеет самое непосредственное отношение к теории и практике обучения. Независимо от того, по какой причине ухудшается успеваемость у школьника, позиция учителя играет решающую роль в преодолении и закреплении этого отставания. К сожалению, нередко формируется порочный круг, когда неудовлетворительные оценки, следуя одна за другой, не стимулируют ученика к более интенсивному обучению. Они, как правило, окончательно подрывают его веру в свои возможности, надежду на улучшение своего положения и в конечном счете интерес к учебе. В связи с этим его знания и умение их продемонстрировать продолжают ухудшаться. Это обстоятельство, в свою очередь, влечет за собой дальнейшее снижение оценок. В результате достаточно быстро развивается обученная беспомощность. Особо вредное воздействие оказывает сопоставление такого ученика с одноклассниками, а также отношение учителя к нему как к аутсайдеру, безнадежно отстающему. Учителя, позволяющие себе реплики типа "Ты все равно никогда не научишься" или "Ты у меня никогда не будешь иметь хороших оценок", сами вгоняют ученика в обученную беспомощность. Если такое отношение не декларируется, оно обычно ярко проявляется в самом стиле обращения с учеником: в мимике, в интонациях, в жестах - и безошибочно определяется как самим учеником, так и его товарищами. Для ребенка или подростка, столь зависимого в своей самооценке от мнения окружающих, особенно тех, кого он уважает, такого отношения может быть достаточно для окончательной утраты веры в себя.

Необходимо иметь в виду, что для ученика несущественно, предъявляются ли ему упреки в недостаточной сообразительности или в лени, в плохом усвоении материала или неумении сосредоточиться. Это обстоятельство обычно упускается из виду. Предполагается, что такие черты, как лень, повышенная отвлекаемость целиком подчинены самоконтролю, а потому нужно разнообразными наказаниями заставить ученика бороться с этими недостатками. Однако дефект воли, который лежит в основе лени и неумения сконцентрироваться на материале, может восприниматься как постоянно действующий и неустранимый фактор, и каждый новый неуспех только укрепляется эту установку.

В данном случае происходит, можно сказать, взаимное обучение беспомощности, ибо плохие оценки ученика, используемые учителем как способ наказания, вызывают у последнего ощущение своего бессилия и тем самым обостряют подспудное раздражение и досаду.

У ученика же обученная беспомощность проявляется во всех аспектах: снижается интерес к учебе, не замечаются собственные успехи, даже если они всё же иногда случаются, нарастает эмоциональное напряжение. В свете изложенного совершенно иначе воспринимаются такие типичные способы работы самооправдания отстающих учеников, как ссылка на необъективность, повышенную требовательность учителя или на невезение и случайности. В этих аргументах прослеживается не только малодушное стремление сложить с себя ответственность, но и вполне оправданная попытка защитится от установок, которые способны превратить обученную беспомощность в стабильное состояние. Ведь приписывание поражений неудачному стечению обстоятельств, которые всегда могут измениться, или предвзятому отношению одного конкретного человека способствует сохранению веры в собственные возможности и ограничивает прогноз будущих неудач. Но, разумеется, поощрять такой стихийно выбранный способ психологический защиты тоже нельзя. Ведь от того, что подросток утвердился в своем недоверии и страхе по отношению к учителю, успеваемость, во всяком случае по этому предмету, не улучшится, а для духовного развития уверенность в несправедливости педагога безусловно вредна.

Как неоднократно уже подчеркивалось, основной задачей школы является формирование личности, а для становления личности обученная беспомощность является более вредной, чем для получения образования. Обученная беспомощность, отказ от поиска - это болезнь личности и регресс в ее развитии. Для преодоления этого состояния все средства хороши. Любые интересы (не имеющие, разумеется, антисоциального характера) должны поощряться, для того чтобы помочь человеку избавиться от обученной беспомощности и укрепить отношения с окружающими. В определенном смысле учителя, родители и друзья должны выполнять функцию психотерапевта, ибо, подчеркиваем, отказ от поиска - болезнь души, угрожающая также и здоровью тела. С болезнью этой очень трудно, почти невозможно справиться в одиночку. Опора, которую может найти молодой человек в теплом отношении близких, является здесь незаменимой. Само собой разумеется, что эта опора не имеет ничего общего с поощрением и принятием пассивного поведения, лени и уклонения от обязанностей. Обучение, ведущее к беспомощности, само является беспомощным (http://www.voppsy.ru/journals_all/issues/1999/991/991013.htm; см. статью А.Н. Поддъякова "Противодействие обучению и развитию как психолого-педагогическая проблема").

Какую же общую мотивацию следует формировать у учащихся?

Чтобы ответить на этот вопрос, надо сначала определить те виды деятельности, которые должны быть главными, ведущими в учебно-воспитательной самодеятельности учащихся. Исходя из цели школы, по мнению Л.М. Фридмана (Фридман Л.М., 1997; аннотация), можно выделить следующие виды деятельности учащихся, определяющие осуществление цели школы:

Чтобы ответить на этот вопрос, надо сначала определить те виды деятельности, которые должны быть главными, ведущими в учебно-воспитательной самодеятельности учащихся. Исходя из цели школы, по мнению Л.М. Фридмана (Фридман Л.М., 1997; аннотация), можно выделить следующие виды деятельности учащихся, определяющие осуществление цели школы:

In order for students to master the activities and the latter to be sufficiently effective, it is necessary to form among them a persistent interest in these activities, as well as all kinds of broad social and internal motives, while ensuring that they are clearly aware, persistent and meaningful.

The development of internal motivation exercises. The development of internal motivation of learning occurs as a shift of the external motive to the goal of learning.

Each step of this process is a shift of one motive to another, more internal, closer to the goal of learning. Therefore, in the motivational development of the student should be considered, as well as in the learning process, the zone of proximal development.

The development of the internal motivation of the teaching is an upward movement. It is much easier to move down. Often, in the real pedagogical practice of parents and teachers, such “pedagogical reinforcements” are used, which lead to a regression of the motivation of learning for schoolchildren. They can be: excessive attention and insincere praise, unjustifiably inflated estimates, material encouragement and use of prestigious values, as well as harsh punishments, diminishing criticism or complete disregard, unjustifiably low estimates and deprivation of material incentives and other incentives.

These effects determine the orientation of the student on the motives of self-preservation, material well-being and comfort.

Shifting a motive to a goal depends not only on the nature of the pedagogical influences, but also on what intrapersonal ground and the objective situation of the teaching they fall on. Therefore, a necessary condition for the developmental shift of the motive to the goal is the expansion of the life world of the student (Milman VE, 1987. p. 136-138).

It was stated above that the necessary motives that should be formed among students in order to realize the main goal of the school - education of the individual are broad social motives and all internal motives, first of all the motives of self-development, self-education and self-improvement, as well as interests in relevant self-development activities, self-education and self-improvement. How to form such motives, interests and inclinations?

A.K. Markova emphasizes that the motives of all kinds and levels can take place in their development the following stages: the actualization of habitual motives; setting on the basis of these motives new goals; positive reinforcement of the motive in realizing these goals; the emergence on this basis of new motives; the coordination of different motives and the construction of their hierarchy; the emergence of a number of motives of new qualities (independence, sustainability, etc.).

L.M. Friedman identifies two main ways of forming the necessary motivation among students (Fridman LM, 1997).

The first way , sometimes called "bottom-up", is to create such objective conditions, such an organization of students' activities, which necessarily lead to the formation of the necessary motivation. This path means that the teacher, relying on the needs already existing in the students, organizes certain activities in such a way that it causes them to have positive emotions of satisfaction and joy. If students have these feelings for a long time, then they have a new need - for this activity itself, which causes them to have pleasant emotional experiences. In the general motivation of schoolchildren, the new enduring motive for this activity is included.

Here is one of many examples of the formation of the necessary motives using this path. Suppose we want to form a strong motive among students — an interest in solving problems, if they have no such motive. Based on the students' need to fulfill the requirements of adults, the teacher organizes independent problem solving in such a way as to guarantee the complete success of each student in this matter, for example, students are given obviously easy tasks. At the same time, the teacher praises the students for successfully completed work and repeats this until the students have full confidence in their abilities in solving problems. Then the teacher, warning that now he will give them complex tasks, again gives them light enough, feasible for each student. Thus, students gradually gain confidence in their abilities and capabilities, they themselves ask for new and new tasks for them, and with increased difficulty. Then the teacher begins to increase the degree of difficulty of the tasks, and thus the students manage to form a strong positive motivation to solve problems of any difficulty.

The second way is to assimilate to the educated the impulses, goals, ideals, content of the personality that are presented to him in the finished "form", which, according to the plan of the educator, should be formed in him and which the educated person should gradually turn from externally understood into internally accepted and actually acting. This is a top-down formation mechanism.

This path is associated with the methods of persuasion, explanation, suggestion, information, example. A special role here is played by the collective, the social environment in which the student lives and acts, the views, beliefs, traditions adopted in this environment. When a student sees that the companions and adults around him treat this or that object (for example, knowledge in some subject, work, etc.) as a special value and direct their activities towards mastering this object. then he takes this look at the object. Thus, the student has a special relationship with this object as a kind of value and the need to master it, i.e. there is a new strong motive.

As indicated by LM. Friedman, a teacher in his educational work, must use both of these paths to form the right motivation of students. In addition, the formation of motivation is influenced by the content of school subjects, the organization of the educational process, extracurricular and extracurricular work, the personality of the teacher and many other factors (for example, the attitude of the student’s family to teaching, upbringing and much more). "... We will especially emphasize the factor of the traditions of the school, the nature of life in school, the interest of teachers in the process of educating students, their enthusiasm for this difficult and complex matter. Indeed, the indifference of some teachers is no less infectious than the enthusiasm of others" (Ibid.).

A.N. Leontyev wrote: "... And in the teaching, too, in order not to formally master the material, you need not to leave the training, but to live it, you need the training to come to life, so that it has a vital meaning for the student. Even in teaching skills to ordinary skills, this is also true. Even the methods of bayonet fighting cannot be properly mastered if there is no inner attitude to it as a motive, and everything looks like a naked technique of “long shots” and “short shots”, “beats up” and “chops down”. Even here useful old classic "angry!", Which is from time immemorial centuries was required of the Russian soldier "(A. Leontiev, 1947. p. 379). "Get mad!" means nothing more than a demand for interest in the business result of the activity being mastered, although both the subject and the product of this activity are merely an imitation of its future real structural entities. Analysis of this statement A.N. Leontyev makes it possible to see that the expression “to have a vital meaning” for him meant that the teaching should act not as self-sufficient knowledge, but rather as a preparatory functional component (or, as AN Leontyev would say, “preparation phase”) of the future “business "activities, i.e. activities performed on the basis of subject-specific, external in relation to the cognition of motive. Of course, it would be a stretch to say that a scientist describes a situation of labor training here: the main driving force for mastering is still a cognitive motive. At the same time, there is a kind of “doubling”, when an ideal, imaginary situation (future work activity) is superimposed on the actual situation (assimilation), so that it can be said that the “business” activity is also carried out, albeit mentally, while the student "consumes" that skill or knowledge, which in real terms it only absorbed. Such a “consumption” of the skill being formed gives an additional motivating effect (http://www.pirao.ru/strukt/lab_gr/g-fak.html; see the research group on personality formation factors).

In order to form persistent positive motivation among students, it is necessary to follow the development dynamics of the motives of learning and self-education in order to timely adjust their pedagogical activity, their individual impact on individual students. To do this, it is necessary to periodically conduct a survey of all students in order to identify the nature of the motivation of their learning, the establishment of the dominant motive.

Of course, a survey, a study of the dynamics of students' personal development is carried out not only to identify motivation, but we will discuss this issue in detail in one of the following paragraphs, but for the time being we will only indicate how the nature of student motivation can be identified.

In addition to observations, you can use various kinds of questionnaires, conversations, essays with the aim of more accurately identifying subjectively conscious motives, interests of students and aptitudes.

You can use some techniques of a more objective nature. L.M. Friedman gives the following methods (Friedman LM, 1997; abstract).

The technique of "free tasks" . At the end of the lesson, the teacher offers students some optional tasks, warning that they are only desirable but useful, for example, for deeper learning of the educational material. He must warn that no marks for this assignment will be given.

It is obvious that the implementation of such tasks indicates the internal interest of students to this academic subject. If such free assignments are used infrequently, but systematically, then, based on their results, it is possible to determine with great reliability the nature of the students' motivation.

Method of interrupting the process of solving problems. She assumes that the student’s independent return to an unsolved task is carried out if he has an intrinsic motivation, revealing one of the manifestations of the cognitive motive in him - the striving for completeness of training activities. This technique can be applied in two versions.

The first option . In the process of the lesson, the teacher sets some rather difficult task for the students. After discussing various ways to solve it, the teacher, having made sure that the task is understood and the students can solve it, leaves the class specifically, finding some excuse for this. When leaving, he gives no instructions to the students. After 10–15 minutes, the teacher returns and, bypassing the students, fixes who solved the problem and who did an entirely different job. Thus, it reveals the presence of students persistent teaching and cognitive motives.

The second version of this technique is that the teacher calculates the lesson time in such a way that the students can only sort out the proposed task, but not complete its solution. When the bell rings, the teacher does not give any task to the students. And in the next lesson, he records which student continued to solve the problem or even solved it completely.

Methods of drawing up tasks and questions. Before completing the next topic, the teacher addresses the class: “We finish studying the topic. In order to summarize the training material and determine the level of its learning by each of you, to identify those questions that are not sufficiently learned, we will conduct a generalizing lesson (test lesson, written work, etc., depending on the specifics of the academic subject.) For this, I ask who wishes, it is possible by teams, to compose a set of questions (a variant of written work, etc.), on which we will generalize the topic. Your suggestions we will discuss in the next lesson. "

By collecting student offers, the teacher can judge the interests of the students and the nature of their motivation by the nature and originality of these proposals.

Learning activities are always polymotivated. Motives for learning activities do not exist in isolation. Most often they appear in a complex intertwining and interconnection. Some of them are of primary importance in stimulating educational activities, others are complementary. It is considered that social and cognitive motives are psychologically more significant and more often manifest.

Learning motives differ not only in content, but also as they become aware. The motives associated with a close perspective in learning are most adequately recognized. In some situations, learning motives remain disguised, i.e. hard to detect.

Comments

To leave a comment

Pedagogical psychology

Terms: Pedagogical psychology