Lecture

The teaching profession owes its origin to the separation of education into a special social function, when a specific type of activity was formed within the structure of the social division of labor, the purpose of which is to prepare the younger generations for life based on their familiarization with the values of human culture (Munsterberg, 1997; see summary) .

The teaching profession owes its origin to the separation of education into a special social function, when a specific type of activity was formed within the structure of the social division of labor, the purpose of which is to prepare the younger generations for life based on their familiarization with the values of human culture (Munsterberg, 1997; see summary) .

Many theorists-teachers noted the enormous moral impact, the powerful and wise power of the teaching profession. Plato wrote that if the shoemaker is a bad master, the citizens will only be a little worse shod, but if the teacher of the children doesn’t fulfill their duties, there will be whole generations of ignorant and bad people in the country. Teacher, emphasized Ya.A. Komensky, was awarded an excellent position, above which nothing can be under the sun. He conducted a series of brilliant analogies between a teacher and a gardener, a teacher and an enterprising architect, he likened the teacher to an eager sculptor who painted and polished people's minds and souls. KD Ushinsky considered the teacher as a warrior of truth and good, as a living link between the past and the future, an intermediary between what was created by past generations and new generations. His business, modest in appearance, is one of the greatest affairs in history. If the teacher believed L.N. Tolstoy, has only love for the cause, he will be a good teacher. If the teacher has only love for the students, like a father, mother, he will be better than the teacher who read all the books, but has no love for the work, nor for the students.

Many theorists-teachers noted the enormous moral impact, the powerful and wise power of the teaching profession. Plato wrote that if the shoemaker is a bad master, the citizens will only be a little worse shod, but if the teacher of the children doesn’t fulfill their duties, there will be whole generations of ignorant and bad people in the country. Teacher, emphasized Ya.A. Komensky, was awarded an excellent position, above which nothing can be under the sun. He conducted a series of brilliant analogies between a teacher and a gardener, a teacher and an enterprising architect, he likened the teacher to an eager sculptor who painted and polished people's minds and souls. KD Ushinsky considered the teacher as a warrior of truth and good, as a living link between the past and the future, an intermediary between what was created by past generations and new generations. His business, modest in appearance, is one of the greatest affairs in history. If the teacher believed L.N. Tolstoy, has only love for the cause, he will be a good teacher. If the teacher has only love for the students, like a father, mother, he will be better than the teacher who read all the books, but has no love for the work, nor for the students.  If the teacher combines the love of the work and to the students - he is a perfect teacher. As A.S. Makarenko, the students will forgive their teachers dryness and even pickyness, but they will not forgive the poor knowledge of the case. Highest of all they value in the teacher mastery, a deep knowledge of the subject, a clear thought. Not a single teacher, considered V.A. Sukhomlinsky (Sukhomlinsky VA, 1979; see annotation), can not be a universal (and therefore abstract) embodiment of all the virtues. In each, something prevails, each has a unique content, it is able to reveal more clearly and fully, to reveal itself in some sphere of spiritual life. This area is precisely the personal contribution that the teacher’s personality makes to the complex process of influencing students. L.S. Vygotsky (Vygotsky LS, 1996; see annotation) (Chrest. 12.1).

If the teacher combines the love of the work and to the students - he is a perfect teacher. As A.S. Makarenko, the students will forgive their teachers dryness and even pickyness, but they will not forgive the poor knowledge of the case. Highest of all they value in the teacher mastery, a deep knowledge of the subject, a clear thought. Not a single teacher, considered V.A. Sukhomlinsky (Sukhomlinsky VA, 1979; see annotation), can not be a universal (and therefore abstract) embodiment of all the virtues. In each, something prevails, each has a unique content, it is able to reveal more clearly and fully, to reveal itself in some sphere of spiritual life. This area is precisely the personal contribution that the teacher’s personality makes to the complex process of influencing students. L.S. Vygotsky (Vygotsky LS, 1996; see annotation) (Chrest. 12.1).

Many authors define the pedagogical activity of a teacher as the educating and teaching influence of a teacher on a student, aimed at his personal, intellectual and activity development, simultaneously acting as the basis of his self-development and self-improvement (IA Zimnyaya, 1997, Markova AK, 1993) () http://elite.far.ru/index.phtml?page=book5314000822).

Klimov E.A. (Klimov, EA, 1996) a scheme of characteristics of professions was developed. According to this scheme, the object of the pedagogical profession is a person, and the subject is the activity of its development, upbringing, and training. Pedagogical activity belongs to the group of professions "person - person) (see animation).

(http://elite.far.ru/; see the website of the Department of Acmeology and Psychology of Professional Activity of the RAGS),

(http://www.psy.msu.ru/about/kaf/industr.html; see the Department of Labor Psychology and Engineering Psychology, Moscow State University),

(http://www.voppsy.ru/journals_all/issues/1999/995/995122.htm; see EI Isayev, "The contribution of S. L. Rubinstein to the psychological training of teachers").

Each activity has its own subject, just as pedagogical activity has its own.

The subject of pedagogical activity is the organization of educational activities of students, aimed at the development by students of the subject socio-cultural experience as the basis and condition for development.

The specific characteristic of pedagogical activity is its productivity. N.V. Kuzmina (Kuzmina N.V., 1990. C.13; see annotation) identifies five levels of pedagogical activity:

The specific characteristic of pedagogical activity is its productivity. N.V. Kuzmina (Kuzmina N.V., 1990. C.13; see annotation) identifies five levels of pedagogical activity:

Level I - (minimal) reproductive; The teacher can and is able to tell others what he knows himself; unproductive .

Level II - (low) adaptive ; the teacher is able to adapt his message to the characteristics of the audience; unproductive .

Level III - (medium) locally modeling ; The teacher has knowledge of the strategies for teaching students knowledge, skills, and skills in individual sections of the course (that is, they can formulate a pedagogical goal, be aware of the desired result, and select the system and sequence of inclusion of students in educational activities; medium-productive .

Level IV - (high) system-modeling knowledge of students; the teacher has strategies for the formation of the desired system of knowledge and skills of students in their subject as a whole; productive .

Level V - (the highest) system-modeling activities and behavior of students; The teacher has strategies for turning his subject into a means of shaping the student’s personality, his needs for self-education, self-education, and self-development; highly productive (Fig. 5).

The self-concept is a generalized self-image, a system of attitudes relative to one’s own personality .

In psychology, self-consciousness, or “I,” means either the process of accumulating ideas about oneself, or the result of this process.

All these various aspects of the “I” -fomen are integrated into individuals as a whole, into a certain system consisting of various, sometimes even contradictory elements.

There are the following functions of self-awareness in human life :

1. "I" is the point, the perspective from which a person perceives and comprehends the world. Moreover, any individual knowledge and experience has a subjective coloring in the sense that a person relates this knowledge to his own personality, to his own “I”, i.e. this is my knowledge, my experience.

2. Self-consciousness, "I", performs a regulatory role in human life. Human behavior, unlike animal behavior, is caused not only by the situation, but also by how the person perceives and evaluates himself.

The mental mechanism of the formation of self-consciousness is reflection, i.e. the ability of a person to mentally go out of a subjective point of view and approach oneself from the point of view of other people. By accumulating the experience of perceiving oneself from different points of view, in different situations and integrating it, a person forms his self-consciousness.

It is important to note that the self-concept is not a static, but a dynamic psychological entity. The formation, development and change of the self-concept is determined by factors of the internal and external order. Social environment has the strongest influence on the formation of self-concept. Professional self-concept of personality can be real and perfect.

The concept of "real" does not imply that this concept is realistic. The main thing here is the idea of a person about himself, about "what I am." The ideal self-concept (the ideal “I”) is a representation of the personality about itself in accordance with desires (“what would you like to be”).

Of course, the real and ideal self-concepts not only may not coincide: in most cases they are necessarily different. The discrepancy between the real and the ideal self-concept can lead to different negative and positive consequences. On the one hand, the disagreement between the real and the ideal "I" can become a source of serious intrapersonal conflicts. On the other hand, the discrepancy between the real and the ideal professional self-concept is the source of the professional self-improvement of the individual and the desire for its development. It can be said that much is determined by the measure of this discrepancy, as well as by its intrapersonal interpretation (Pryazhnikov, NS, 1996; see annotation).

Professional activity is one of the main forms of human activity.On how a person perceives and assesses his work, his achievements in a particular activity and himself in a professional situation, his general well-being and his effectiveness also depend. Professional self-identity is the main source and mechanism for professional development and improvement (Orlov Yu.M., 1991; see annotation).

Professional activity is one of the main forms of human activity.On how a person perceives and assesses his work, his achievements in a particular activity and himself in a professional situation, his general well-being and his effectiveness also depend. Professional self-identity is the main source and mechanism for professional development and improvement (Orlov Yu.M., 1991; see annotation).

Для педагогической деятельности проблема профессионального самосознания приобретает особую актуальность потому, что результаты деятельности учителя выражаются, прежде всего, в результате учебной деятельности учащихся, и способность учителя анализировать и оценивать свою деятельность и ее результаты, свои профессионально значимые качества непосредственно связана с эффективностью педагогического воздействия. Кроме того, профессиональное самосознание является личностным регулятором профессионального саморазвития и самовоспитания учителя.

"Актуальное Я" является центральным элементом профессионального самосознания учителя, который основывается на трех других, где "Я-ретроспективное" в отношении к "Я-актуальному" дает учителю шкалу собственных достижений или критериев оценки собственного профессионального опыта; "Я-идеальное" является целостной перспективой личности на себя, которая обуславливает саморазвитие личности в профессиональной сфере; "Я-рефлексивное" - социальная перспектива в самосознании учителя или школьной профессиональной среды в личности учителя.

The most frequently experimentally studied element of self-awareness is self-esteem . Usually, the subjects are offered a list of qualities, abilities, and character traits with which to characterize themselves. Then the same subjects are evaluated by the same qualities by the competent judges. The ratio of self-esteem and judicial evaluation is called the adequacy of self-esteem , which shows how well a person sensibly and accurately perceives and evaluates himself.

Therefore, self-esteem of professional abilities of ranks and achievements can be considered as an essential element in the structure of a professional self-concept of personality.

"Самооценка" является понятием более частным в сравнении с понятием "самоотношение", которое описывает общую направленность и "знак" отношения человека к самому себе. Самооценка является конкретным выражением самоотношения, часто представляемым даже количественно.

В структуре самооценки вообще и профессиональной самооценки в особенности целесообразно выделять аспекты:

а) операционально-деятельностный;

б) личностный.

Операционально-деятельностный аспект самооценки учителя связан с оценкой себя как субъекта деятельности и выражается в оценке своего профессионально-педагогического уровня (сформированность умений и навыков) и уровня компетентности (системы знаний). Личностный аспект профессиональной самооценки учителя выражается в оценке своих личностных качеств в связи с идеалом образа "Я-профессионального". Самооценка по этим двум аспектам не обязательно согласованна. Дискордантность (рассогласование) самооценки по операционально-деятельностному и личностному аспектам влияет на профессиональную адаптацию, профессиональную успешность и профессиональное развитие.

В структуре профессиональной самооценки целесообразно также выделять: а) самооценку результата и б) самооценку потенциала.

Самооценка результата связана с оценкой достигнутого (в общем и парциальном аспекте) и отражает удовлетворенность/неудовлетворенность достижениями.

Самооценка потенциалаassociated with the assessment of their professional capabilities and thus reflects self-confidence and self-reliance. Low self-esteem of the result does not necessarily mean a "professional inferiority complex." On the contrary, low self-esteem results in combination with high self-esteem potential is a factor in professional self-development. The specified self-assessment pattern underlies the positive motivation of self-development and correlates with the social and professional success of an individual, including in educational activities.

Исследования А. Реан (Реан А.А. и др., 2000; см. аннотацию) показали, что образ "Я" у педагогов наиболее отдален от идеала по таким качествам, как уступчивость, лидерство и доверчивость (методика Лири). Причем по лидерству отклонение отрицательное, а по двум другим качествам - положительное. Это означает, что лидерство, по самооценке педагогов, выражено у них недостаточно; имеется желание развивать в себе это качество, приближаясь к "идеальному" образу педагога-профессионала. Но фактически исследование сформированности "лидерства" у педагогов показало, что оно у них достаточно выражено и соответствует адаптивному уровню развития. Дальнейшее усиление этой тенденции свидетельствует о формировании дезадаптивного варианта развития по нарастанию авторитарности и связанности с такими качествами личности, как властность и деспотичность.

Исследования А. Реан (Реан А.А. и др., 2000; см. аннотацию) показали, что образ "Я" у педагогов наиболее отдален от идеала по таким качествам, как уступчивость, лидерство и доверчивость (методика Лири). Причем по лидерству отклонение отрицательное, а по двум другим качествам - положительное. Это означает, что лидерство, по самооценке педагогов, выражено у них недостаточно; имеется желание развивать в себе это качество, приближаясь к "идеальному" образу педагога-профессионала. Но фактически исследование сформированности "лидерства" у педагогов показало, что оно у них достаточно выражено и соответствует адаптивному уровню развития. Дальнейшее усиление этой тенденции свидетельствует о формировании дезадаптивного варианта развития по нарастанию авторитарности и связанности с такими качествами личности, как властность и деспотичность.

Thus, this desire to get closer to the "ideal", rather, leads away from truly productive models of pedagogical communication. It seems that this distorted idea of the ideal of the teacher as a powerful, dominant personality reflected the ideas of authoritarian pedagogy rooted in the mind.

Such qualities as pliability and gullibility, according to the teachers' self-assessment, are expressed by them too much. And, therefore, they believe that in order to approach the professional ideal of the “I”, it is necessary to become less pliable and less trusting.

Оказывается, чем оптимальное мотивация профессиональной деятельности педагога, чем больше выражены у него внутренние и внешние положительные мотивы, тем активнее он стремится ограничить свою властность. Именно для данной категории педагогов характерно представление о слишком высоком развитии в собственной личности авторитарных тенденций; о том, что работа над собой, приближение к идеалу педагога-профессионала должны идти по пути ограничения властных, жестких, авторитарных начал. И наоборот, чем менее оптимален мотивационный комплекс педагога, чем менее значимы для него собственно внутренние мотивы профессиональной деятельности, тем более связывает педагог свое профессиональное совершенствование с развитием в себе таких качеств, как властность и авторитарность. Именно этих качеств, в его представлении, ему не хватает для приближения к Я-образу профессионального идеала.

Thus, both teachers with internal, productive, motivation, and teachers with non-optimal professional motivation strive for self-improvement. But the paths for this are different: some tend to become less, others more authoritarian. Opposite are their ideas about the directions of self-development, self-correction and ways of approaching the professional ideal.

Между отклонениями самооценки педагога от образа "идеала" по параметрам "лидерство" и "уступчивость" существует не прямая, а обратная, отрицательная зависимость. Иначе говоря, чем больше у педагога выражено стремление развивать в себе лидерские качества, тем больше у него выражена тенденция избавляться в процессе самосовершенствования от "излишней" мягкости, уступчивости. По мнению педагога, от идеала его отдаляет не только слабое выражение лидерского начала, но и слишком высокая уступчивость в общении. И наоборот, тот, кто полагает, что его гипертрофированное "лидерство" нуждается в ограничении, связывает приближение своего профессионального идеала с дальнейшим развитием в себе такого качества, как уступчивость.

The more a teacher seeks to limit negativism in behavior, the less his communicative activity is associated with the transfer of information. The structure of the communicative activity of such teachers is dominated by the processes of receiving information. The more in the structure of the communicative activity of a teacher, the processes of information transfer prevail over the processes of receiving information, the greater the deviation of self-esteem from the ideal in terms of "demanding-intransigence". Moreover, this deviation can be both negative and positive, we can talk about the desire to both increase and decrease its demands. Teachers, mainly focused on the transfer of information, tend to be more demanding than teachers, whose communication activity is dominated by the processes of receiving information.

But no matter how this characteristic of personality is revealed, in all concepts the leading meaning is attached to it. Consider these concepts in more detail.

S.L. Under the direction of personality, Rubinstein understood some dynamic tendencies that determine human activity as motives, themselves, in turn, being determined by its goals and objectives. Orientation includes two interrelated moments: subject content (meaningful moment), denoting a specific object of orientation; voltage (properdynamic tendency), which determines the source of directivity (S. Rubinstein, 1999; see annotation).

S.L. Under the direction of personality, Rubinstein understood some dynamic tendencies that determine human activity as motives, themselves, in turn, being determined by its goals and objectives. Orientation includes two interrelated moments: subject content (meaningful moment), denoting a specific object of orientation; voltage (properdynamic tendency), which determines the source of directivity (S. Rubinstein, 1999; see annotation).

It should be recognized that the question of dynamic trends and the directions they engender as a necessary component of a genuine explanation of mental processes was first put in modern psychology by K. Levin. However, unlike S.L. Rubinstein, he tore off the dynamic aspect of orientation from the semantic, seeking to transform the dynamic moment into a universal mechanism for explaining the human psyche. Z. Freud (1989) considered dynamic tendencies as unconscious drives, the direction of which is the mechanism originally laid in the human body. S.L. Rubinstein, criticizing Freud, noted that any dynamic tendency, expressing directionality, always contains within itself a more or less conscious connection of the individual with something outside of it. At the same time, he admits the possibility of changing the accents of the dynamic and semantic sides of orientation.

A.N. Leontyev (Leontyev AN, 2001; see annotation) the personality core called the system of relatively stable, hierarchized motives as the main motivators of activity. Some motives (sense-forming), prompting to activity, give it a personal meaning and a certain direction, others play the role of incentive factors. The distribution of the functions of sense-formation and motivation between the motives of one activity allows one to understand the main relations characterizing the motivational sphere of a person, i.e. see a hierarchy of motives.

L.I. Bozovic and her staff (Bozhovich LI, 1997; see annotation) the orientation of the individual was understood as a system of persistently dominant motives that define the whole structure of the personality. In the context of this approach, a mature personality organizes his behavior in the context of several motives; chooses activity goals and, with the help of a specially organized motivational sphere, regulates his behavior in such a way that undesirable, even if stronger, motives are suppressed. The structure of orientation consists of three groups of motives: humanistic, personal, business.

L.I. Bozovic and her staff (Bozhovich LI, 1997; see annotation) the orientation of the individual was understood as a system of persistently dominant motives that define the whole structure of the personality. In the context of this approach, a mature personality organizes his behavior in the context of several motives; chooses activity goals and, with the help of a specially organized motivational sphere, regulates his behavior in such a way that undesirable, even if stronger, motives are suppressed. The structure of orientation consists of three groups of motives: humanistic, personal, business.

Almost all psychologists by the direction of the individual understand the totality or system of any motivational formations, phenomena . B.I. Dodonova is a system of needs; by K.K. Platonov - a set of drives, desires, interests, inclinations, ideals, worldview, beliefs; at L.I. Bozovic and R.S. Nemova - a system or set of motives, etc. However, the understanding of the orientation of the individual as an aggregate or system of motivational formations is only one side of its essence. The other side is that this system determines the direction of behavior and human activity , orients it, determines the tendencies of behavior and actions and, ultimately, determines the person's appearance in social terms. The latter is due to the fact that the orientation of the individual is a stably dominant system of motives, or motivational formations, i.e. reflects the dominant, becoming a vector of behavior (Ilyin EP, 2000; see annotation).

Orientation of personality, as noted by V.S. Merlin (Merlin VS 1986), can manifest itself in relation to other people, to society, to himself. M.S. Neymark (1968), for example, emphasized the personal, collectivistic, and business orientation of the individual.

The humanistic orientation is characterized by a positive attitude of the individual towards himself and society. Inside this type, the authors distinguish two subtypes: with an altruistic accentuation , in which the interests of other people or a social community are the central motive of behavior, and with an individualistic accentuation , in which he himself is the most important person, surrounding people are not ignored, but their value , compared with its own, slightly lower (Belukhin DA, 1994; see annotation).

The humanistic orientation is characterized by a positive attitude of the individual towards himself and society. Inside this type, the authors distinguish two subtypes: with an altruistic accentuation , in which the interests of other people or a social community are the central motive of behavior, and with an individualistic accentuation , in which he himself is the most important person, surrounding people are not ignored, but their value , compared with its own, slightly lower (Belukhin DA, 1994; see annotation).

The egoistic orientation is characterized by a positive attitude towards oneself and a negative attitude towards society. Inside this type, two subtypes are also distinguished: with individualistic accentuation , the value of a person’s self is as high as with a humanistic orientation with individualistic accentuation, but the value of others is even lower (negative attitude towards others), although absolute rejection and ignoring their speech is not; with egocentric accentuation - the value of the self for a person is not very high, he concentrates only on himself; society for him represents almost no value, the attitude towards society is sharply negative.

The depressive orientation of the personality is characterized by the fact that he himself does not represent any value, and his attitude to society can be characterized as tolerable (Zhutykova NV, 1988; see annotation).

The depressive orientation of the personality is characterized by the fact that he himself does not represent any value, and his attitude to society can be characterized as tolerable (Zhutykova NV, 1988; see annotation).

Suicidal tendencies are observed in cases where neither society nor a person has any value for itself.

Such an allocation of types of orientation shows that it can be determined not by a complex of some factors, but only by one of them, for example, by personal or collectivist attitudes, etc. In the same way, the orientation of a person can be determined by a single over-developed interest. Thus, the structure of the orientation of the individual can be simple and complex, but the main thing in it is the steady dominance of some need, interest , as a result of which a person “persistently seeks the means to initiate the experiences he needs as often as possible and stronger”.

However, reducing the orientation of the individual simply to the needs, interests, worldview, belief or ideals is inappropriate. Only sustained dominance of need or interest, acting as long-term motivational attitudes , can form the core line of life. In this regard, E.P. Ilyin (Ilyin EP, 2000; see annotation) stresses that the inherent operational motivational attitude properties that determine readiness and specific behaviors and actions of a person in a given situation are not enough to be considered one of the types of personality orientation. Directs actions and activities, and any goal. The installation should become steadily dominant, and such are most often social attitudes related to interpersonal and personal-social relations, attitudes towards work, etc. Thus, he concludes that the orientation of the individual in the motivational process attracts and directs the person’s activity, i.e. to some extent facilitates the decision on actions in this situation.

So, having considered the orientation of the individual in the context of general psychological approaches, we need to more concretely and see the orientation of the individual in the field of pedagogical activity ( pedagogical orientation ).

One of the main professionally significant qualities of a teacher’s personality is his “personal orientation”. According to N.V. Kuzmina (Kuzmina N.V., 1967, 1990; see annotation), personal orientation is one of the most important subjective factors of reaching the top in professional-pedagogical activity.

A.K. Markova believes that the analysis of the personality of the teacher should begin with the study of orientation, i.e. of what the teacher aims at in his work, whereas abilities as a whole are a more compensable personality trait, they can be formed if a person has a steady desire to be a teacher. Pedagogical orientation is the motivation for the teaching profession, the main one in which is an effective orientation towards the development of the student’s personality. Sustainable pedagogical orientation is the desire to become, to be and to remain a teacher, helping him to overcome obstacles and difficulties in his work. The orientation of the teacher’s personality is manifested in all his professional life and in certain pedagogical situations; it determines his perception and logic of behavior, the whole face of a person. The development of a pedagogical orientation is promoted by a shift in teacher motivation from the subject side of his work to the psychological sphere, an interest in the student’s personality.

N.V. Kuzmina (1967, 1990) by the essence of the pedagogical orientation understands the interest and love for the teaching profession, awareness of difficulties in teaching, the need for teaching, the desire to master the basics of pedagogical skills.

A narrower understanding of the essence of pedagogical orientation is characterized by greater unambiguity and specification of the definition. In this case, pedagogical orientation is understood either as a positive attitude towards pedagogical activity (for example, in TS Derkach), or as an inclination and willingness to engage in pedagogical activity (for example, in G. A. Tomilova). A number of authors of the definition of the essence of pedagogical orientation are associated with the leading motive, the dominant interest (S. A. Zimicheva; EM Nikireyev, S. Kh. Asadullin, etc.).

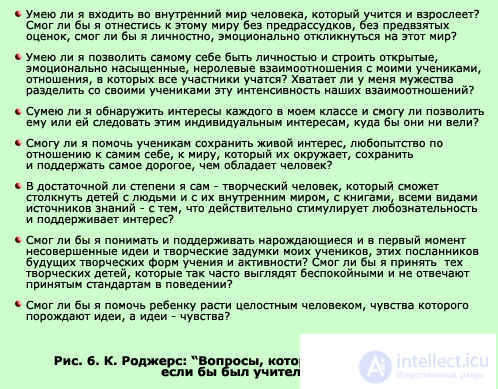

Of particular interest are studies of pedagogical orientation in the direction of humanistic psychology (A. Maslow, C. Rogers, D. Dewey, and others). The orientation of the individual is considered as an indestructible desire of the individual to self-actualization. K. Rogers analyzes the problem of the values of a teacher as a constitutive education of his personality, which in this sense coincides with the pedagogical orientation. Analyzing the controversial nature of the human value system, C. Rogers comes to several serious conclusions: the value aspirations common to people are humanistic in nature and consist in improving the development of man himself; the whole system of positive values does not lie outside the student, but in himself. Therefore, the teacher, according to K. Rogers, can not ask, but can only create conditions for its manifestation (Khrest. 12.2) (Fig. 6).

Most fully, perhaps, the pedagogical orientation is examined in the works of L.M. Mitina, who singled out pedagogical orientation as one of the integral characteristics of the teacher’s pedagogical labor, along with pedagogical competence and emotional flexibility (Mitina LM, 1994; 1998; see annotation, cover).

Most fully, perhaps, the pedagogical orientation is examined in the works of L.M. Mitina, who singled out pedagogical orientation as one of the integral characteristics of the teacher’s pedagogical labor, along with pedagogical competence and emotional flexibility (Mitina LM, 1994; 1998; see annotation, cover).

According to LM. Mitina, the teacher’s desire for self-actualization in the field of pedagogical activity is indeed an indicator of pedagogical orientation. Orientation is an integral characteristic of a teacher’s work, it expresses the teacher’s desire for self-realization, growth and development in the field of pedagogical activity. It largely becomes the motivation for improvement with the most "effective teachers." In this case, it’s about self-actualization, which includes in its definition the promotion of self-actualization of students, and not just "self-creation of one’s own" phenomenal world.

L.M. Mitina puts forward the need to revise the concept of "personal orientation". She believes that the orientation of a person towards herself is not so straightforward: personal orientation has not only an egoistic, egocentric context, but also a desire for self-realization, and therefore, for self-improvement and self-development in the interests of other people.

The pedagogical orientation of the teacher on the child is aimed at developing a student's motivation for learning, knowledge of the world, people, himself.

Pedagogical orientation is considered in both narrow and broad senses. In a narrower sense, pedagogical orientation is defined as a professionally significant quality, which occupies a central place in the structure of a teacher’s personality and determines its individual and typical identity. In a broader (in terms of the integral characteristics of labor) - as a system of emotional-value relations, defining the hierarchical structure of the dominant motives of the teacher’s personality, prompting the teacher to approve it in teaching and communication.

The proposed pedagogical structure is fundamentally different in the place and proportion of the dominant motifs.

According to L.M., psychological condition for the development of pedagogical orientation. Mitina, is the teacher’s awareness of the leading motive of her own behavior, activity, communication, and the need to change it.

The dynamics of pedagogical orientation is determined by the restructuring of the motivational structure of the teacher’s personality from the subject orientation to the humanistic one.

According to LM. Митиной (1998), под склонностью и потребностью в педагогической деятельности исследователи часто понимают готовность заниматься преподаванием определенного предмета, т.е. неправомерно завышается роль предметной направленности учителя в ущерб направленности на ребенка.

N.D. Левитов педагогическую направленность определял как свойство личности (некоторое общее психическое состояние учителя), которое занимает важное место в структуре характера и выступает проявлением индивидуального и типического своеобразия личности. Близок к такому пониманию Ф.Н. Гоноболин (1965, 1972), который в структуре личности учителя выделяет педагогические способности и общие личностные свойства, называя их направленностью. К направленности Ф.Н. Гоноболин относит убежденность учителя, его целенаправленность и принципиальность.

A.I. Щербаков (1981) связывает понимание сущности педагогической направленности с комплексом профессионально-значимых качеств учителя - общегражданских, нравственно-педагогических, социально-перцептивных, индивидуально-психологических, а также умений и навыков. По мнению автора, профессионально-педагогическая направленность коррелирует прежде всего с индивидуально-психологическими качествами личности (высокие познавательные интересы, любовь к детям и потребность в работе с ними, адекватность восприятия ребенка и внимательность к нему, прогнозирование формирующейся личности школьника, определение условий и выбор средств ее всестороннего развития и др.). В рамках этого подхода сущность педагогической направленности определяется через профессионально значимые качества личности учителя, которые представляются рядоположенно.

Yu.N. Кулюткин, Г.С. Сухобская (1983, 1987, 1990) рассматривают педагогическую деятельность как метадеятельность. Основную задачу учителя они видят в построении такой деятельности учащихся, в процессе и в результате которой происходило бы развитие их нравственных убеждений, системы их знаний и познавательных способностей, а также практических умений и навыков. Управление деятельностью учащихся педагог должен строить не как прямое воздействие, а как передачу ученику тех "оснований", из

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 12. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PEDAGOGICAL ACTIVITY

Часть 2 12.4. Мотивация и продуктивность педагогической деятельности - 12. GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

Comments

To leave a comment

Pedagogical psychology

Terms: Pedagogical psychology