In this article I will briefly try to answer the following questions:

- what is a neuron, how does it work and how does it work?

- what happens in synapses when neurons communicate with each other?

And in the next (s):

- how is intelligence and consciousness related to neuron activity? (here it’s about how information is processed by the brain, neuroplasticity, quantum theory of consciousness, sleep, etc.)

So what is a neuron, how does it work and how does it work?

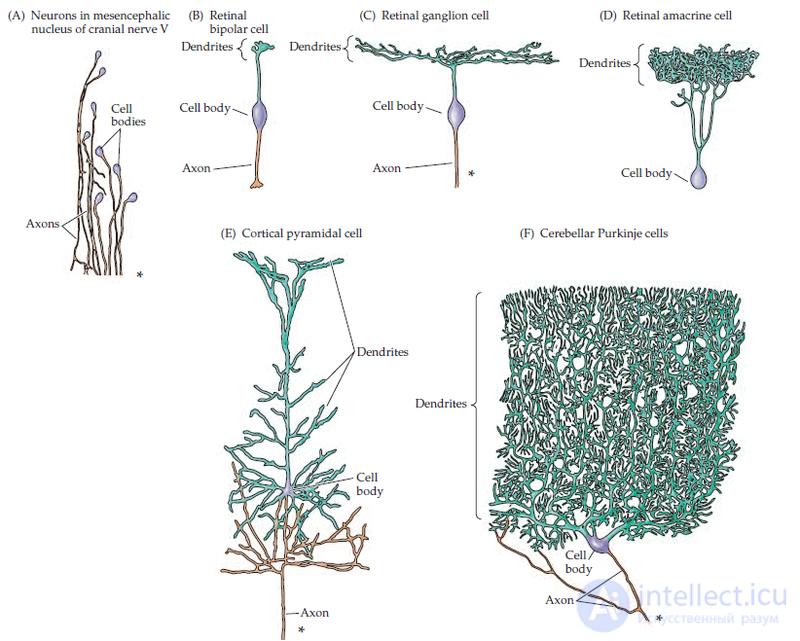

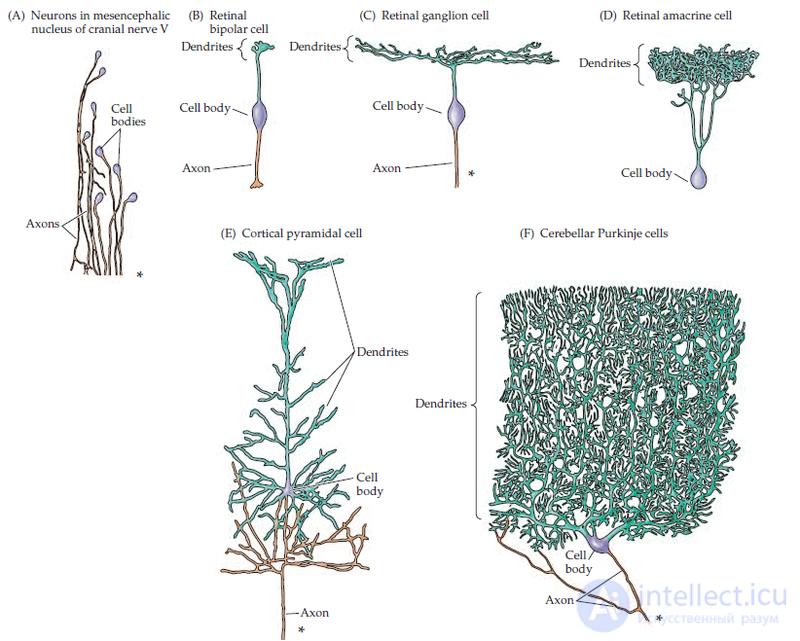

Fig. 1. Various forms of neurons. Here and below, the pictures are from “Neuroscience”, 3d edition, Dale Purves

et al .

First, it is worth mentioning that in the human body there is more than one type of neurons, however, with all their differences (Fig. 1), they have much in common, including in terms of mechanisms to ensure their direct functionality. Secondly, in the brain, in addition to neurons, there are also many auxiliary cells - neuroglia cells, or simply glia. These cells are on average 3 times more than neurons, and they provide neurons with nutrition, energy and necessary substances. Recently, they have been given more and more attention due to the fact that their influence on the work of neurons (for example [1]) in the field of learning and memory has been shown. It would be worthwhile to note that being a support cell, the neuroglia cannot but influence the work of neurons, because a hungry neuron cannot work the same as well-fed, however, they should not overestimate their role in information processing: yes, they affect the work of neurons and synapses, but do not define it. Hence the proverb: fed the hungry does not understand.

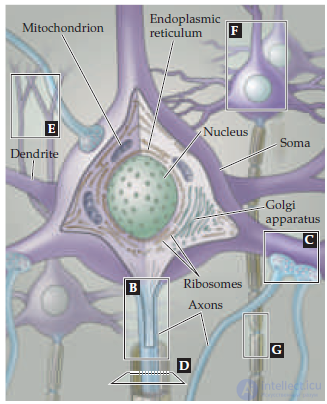

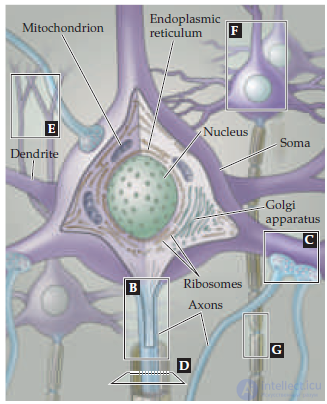

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of the structure of the neuron.

But back to the neurons and signals that they produce. The abstract averaged structure of a neuron is something like the one shown in fig. 2. and consists of the cell body (soma), in which you can find all the elements of a normal living cell (nucleus, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, etc.), dendrites - processes that serve as input from other neurons, and usually one long axon - according to which a neuron broadcasts its opinion to other neurons. All mathematical models of perceptrons went from this structure - many inputs, black box, single output, profit. And what happens in the black box? How does a neuron process incoming signals and what are the mathematical models of neurons based on? It turns out that not everything is as difficult as it could be. Consider, for example, the mechanism of axon operation for signal transmission.

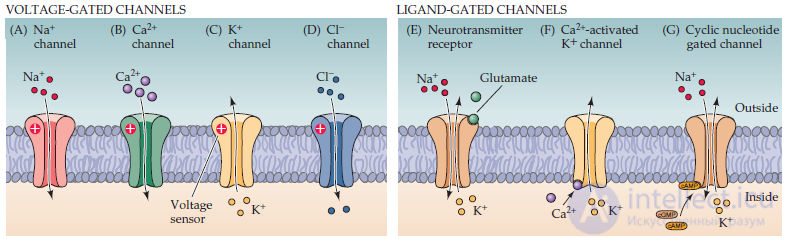

Fig. 3. The structure of the axon with the main active elements for signal propagation: proteins responsible for the transfer of ions from the inside of the cell to the outside and vice versa.

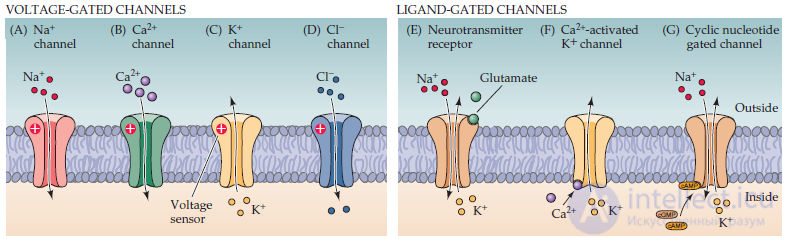

1. Axon structure

As can be seen in Figure 3, the axon is a simple cell membrane consisting of a double layer of lipids, interspersed with various proteins, plus what is not shown in the picture is the cytoskeleton consisting of micro protein tubules and connective proteins. It is important to note that inside and outside the axon the chemical composition of the fluids is different. And, as we will see later, gradients of sodium, potassium, calcium and chlorine ion concentrations play a very important role. Different concentrations of ions on both sides of the membrane are actively supported by just the proteins that are in large quantities in the membrane. Some of them support a certain potential of the membrane, the so-called resting potential (RP): in different organisms it varies from -40 to -90 mV. It turns out due to the fact that special proteins (they are called active transporters) pump unilaterally ions against the concentration gradient, while other proteins (called ion channels) allow certain ions to flow in the opposite direction. The balance of these two processes affects both the RP and the action potential (AP) - the main signal transmitted from one neuron to another, as well as synaptic and receptor potentials, which provide the AR.

2. What is the signal for an axon and where does it come from?

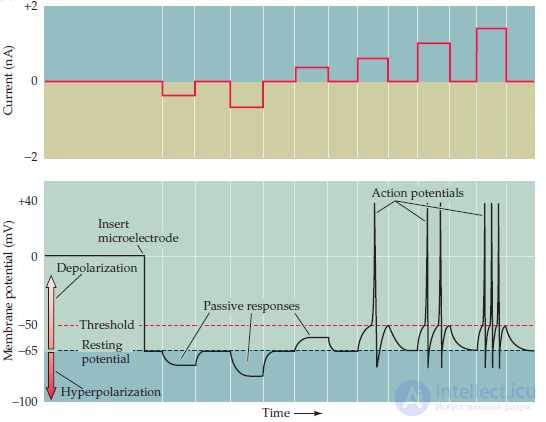

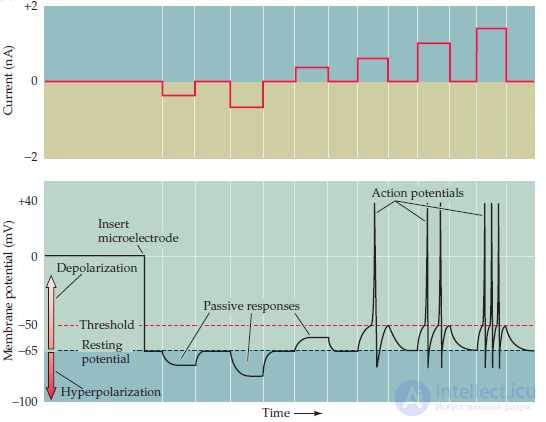

So, since AR is something that is transmitted from one neuron to another, it will be most important for us, therefore, let's consider it in more detail. The work of proteins on the transfer of ions and control of the level of RP within certain limits is quite well organized and even noise-resistant. This can be demonstrated by applying certain potentials to the membrane (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Schematic representation of the conditions for generating passive and active signals.

As can be seen from the diagram, at the equilibrium value of RP, no current flows through the membrane. If an external potential is applied to the membrane, then within certain limits its response will be linear. However, at the intersection of a certain threshold value (Threshold), an “explosive” membrane depolarization occurs - the very action potential. Moreover, it is important to note: by applying greater potential to the membrane, the AR does not become larger or longer, but the repetition rate becomes greater! And there is no magic here: in quiet time, the sodium channels are closed and the sodium concentration gradient is provided by ion transport proteins. However, when crossing the threshold potential of the membrane, the sodium channels turn on and very quickly pass a large amount of ions into the cell, quickly changing the total membrane potential. Potassium channels of such circulation will not be tolerated and will also open, but the equilibrium gradient of potassium concentrations is opposite to the gradient of sodium concentrations, therefore potassium will flow out of the axon, thereby neutralizing the effect caused by sodium and restoring the equilibrium value of RP. Due to the different flow rates of these two processes, an excessively negative membrane potential is formed for a short time, but it is compensated by the operation of ion-transport proteins.

So in fact, the axon is a simple ADC, which encodes the amplitude of the incoming signal with the frequency of the output signals, plus a certain threshold below which it does not tense at all, and transmits this signal further. The propagation of the signal along the axon is regulated by all the same proteins: when the AR appears in one part of the axon, it changes the concentration of ions in a certain neighborhood, and the same thing happens there only with a certain time delay, hence the completely finite speed of propagation of nerve impulses: from 0.5- 10 m / s for short neurons up to 150 m / s for long axons surrounded by myelin.

What happens in synapses when neurons communicate with each other?

To begin, perhaps, it is worth mentioning that a synapse is the connection of the axon of one neuron with the dendrite of another and synapses are of two types: electrical and chemical. The former ones are quite rare, but in fact they provide the ability to transmit an electrical signal directly from one neuron to another. This happens when the synaptic connection of two neurons is so close that they “merge” and the ion channels of one neuron are directly connected to the ion channels of the other neuron, allowing small molecules to move between them. Thus, electrical synapses simply allow ion currents to flow between neurons. An interesting feature of this connection is that it works in both directions. Another feature is that they are extremely fast. Therefore, such synapses are used in populations of neurons that should be well synchronized, for example, which generate rhythmic activity for respiration.

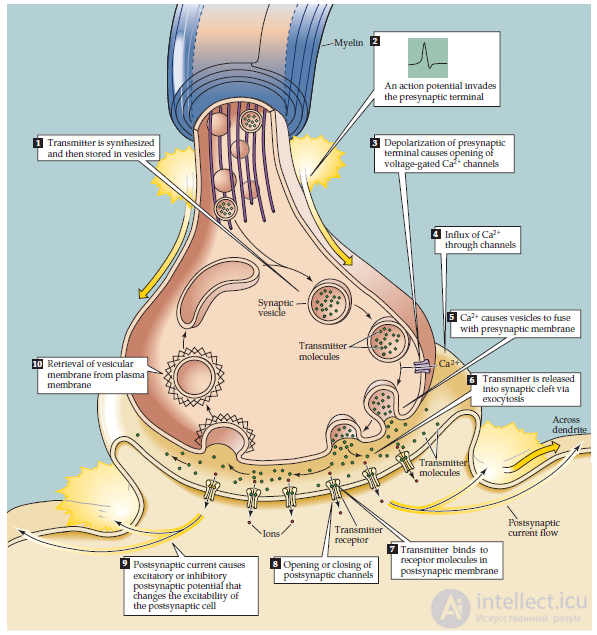

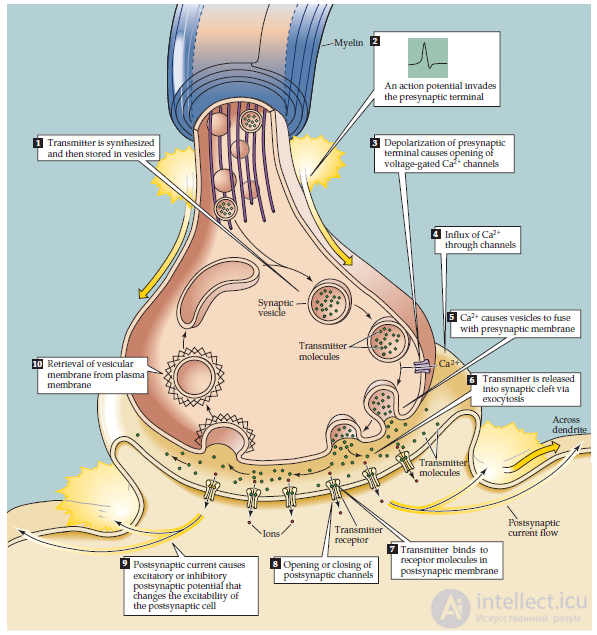

Fig. 5. Full cycle of signal transmission through a chemical axon: 1 - synthesis and storage of the transmitter; 2 - arrival of the AR; 3 - opening of calcium channels under the influence of AR; 4 - the flow of calcium ions through the open channel; 5 - fusion of bubbles with a transmitter with a membrane under the influence of an excessive concentration of calcium ions; 6 - release of the transmitter into the synaptic space; 7 - binding of the transmitter to the receptors on the dendritic side of the synapse; 8 - opening of ion channels under the influence of the transmitter; 9 - formation of AR under the influence of current of ions through the channels; 10 - return of bubbles for filling with a new transmitter.

Chemical synapses work a little differently (Fig. 5). In short, when AP arrives, a neurotransmitter is released from the axon side, which diffuses through the synaptic space and binds to receptors on the dendrite side, activating them. The activated receptors depolarize the dendrite membrane and thereby include the process of dissemination of the AP throughout its membrane. In theory it is simple, but in practice it has become clear that neurotransmitters are under 100 different types. The question is, why so much? Studies have shown that many neurons simultaneously produce several non-transmitters, which, in turn, have a different effect on the receptors of the post-synaptic (signal-receiving) membrane. For example, neurotransmitters of small size, usually secreted by rarely arriving ARs, quickly flow through the synaptic space and cause a quick reaction, while large molecules, released by frequently arriving ARs, move longer, but also bind to receptors more strongly, thereby causing more long-term depolarization of the membrane. All this creates prerequisites for better transmission of the incoming signal. It is also important to note that some neurotransmitters can excite a receiving neuron, while others - on the contrary, inhibit excitation.

Something like that.

So far, about artificial intelligence is not very much happened, but we reach it.

- [1] google "mystery-of-the-human-brains-glia-cells-solved-key-to-learning-information-processing"

Comments

To leave a comment

Models and research methods

Terms: Models and research methods