Lecture

One of the myths about the initial period of the history of computers, usually associated with research and development of American scientists and engineers. This myth was destroyed in 1969, when information about Zuse's computers became available in the United States and other countries.

Konrad Zuse was born on June 22, 1910 in Berlin. His father, Emil Zuse, was a postal official, earned a little, but with his wife Maria Zuse, and Conrad’s sister Lizelotta, he did everything he could to keep his son interested in designing computers.

I must say that as a child, Konrad designed a working model of a coin changer. In 1935, he graduated from a higher technical school (Tecbnische Hochschule) with a degree in civil engineering and began working as an analyst at Henschel. While working at this company, Zuse encountered many tedious calculations related to aircraft design. In 1936, at the age of 26, he decided to design a computing device (computer), having accumulated ideas for this and the parents' apartment as a “workshop”.

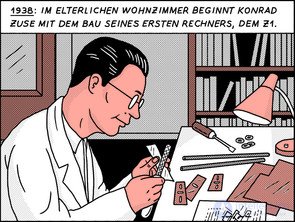

He was going to build a series of computers, originally called Versuchsmodell (an experimental model). The first Versuchsmodell, V-1, built in 1938, was completely mechanical, with 16 machine words and occupied an area of 4 square meters. meters (restored version of the V-1 is in the Verker und Technik Museum in Berlin). Versuchsmodell series Zuse considered as a working tool for engineers and scientists who dealt with complex aerodynamic calculations.

At the beginning of the war, in 1939, Zuse was recruited into the army, but soon he and many engineers like him were released from military service and assigned to engineering projects supporting German military might. Zuse was sent to the German Aviation Research Institute in Berlin.

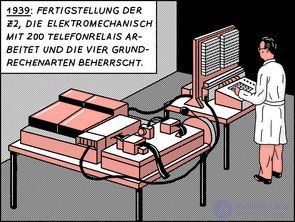

Returning to his hometown, the scientist continued to improve the Versuchsmodell series in his parents' house, and more at his own expense, although he worked at the institute that designed military aircraft for the Luftwaffe. Helmut Schreier, who collaborated with Zuse in creating computers, proposed using electromagnetic relays for the second Versuchsmodell, V-2. Schreier showed Zuse how these relays can be applied in the structure of a digital mechanical computer developed by Zuse. Schreier, who left for Brazil after the war, also considered the possibility of using vacuum tubes to create computers, and ultimately he developed a kind of “trigger scheme”, now widely used in computer logic.

V-2 was, of course, very unreliable, but one of the rare instances of its normal work happened when Alfred Teichman, a leading scientist from the German Aviation Institute, visited the house of Zuse, at his invitation. Teikhman was an expert on the most important problem of aircraft construction - wing vibration. He immediately realized that a car like the V-2 could help engineers solve this problem. The vibration problem “disappeared at the touch of a finger”, later recalled to Zuse.

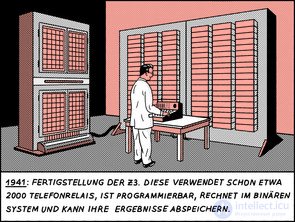

Teichman helped Zuse get money for his work on creating computers, but Zuse continued to work in his parents' home and never hired an outside staff of assistants. With the help of Schreier, Zuse completed the world's first fully functional, software-controlled computer at the end of 1941.

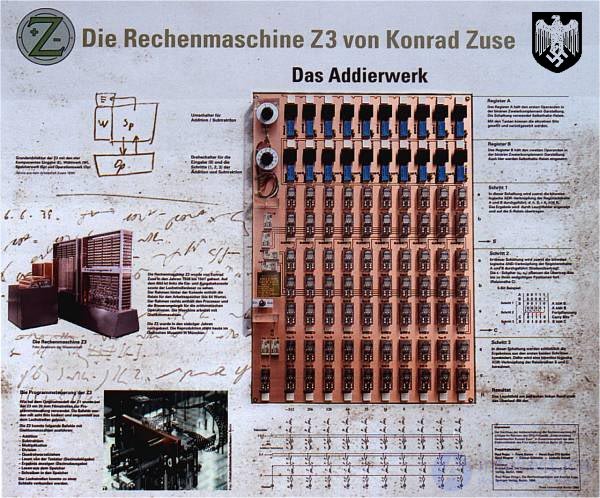

This third Versuchsmodell is called the V-3. He had 1,400 electromagnetic relays in memory, 600 relays for controlling calculations, and another 600 relays for other purposes. The computer worked in a binary number system, the numbers were represented in the form of a floating comma, the length of the machine word was 22 bits, the memory size was 64 bits.

The V-3 multiplication operation took from three to five seconds. The problem most often solved by V-3 was the calculation of the determinant of the matrix (that is, the solution of a system of equations with several variables). V-3 was obviously the first computer to use the reverse Polish notation to write arithmetic expressions. The invention of this recording system is attributed to Polish logic Yan Lukasevich, but Zuse did not know about Lukasevich’s contribution, he simply reinvented the “wheel”, like many other scientists.

During World War II, Zuse re-named his first three computers as Zl, Z-2, Z-3, respectively, to avoid confusion with the V-1 and V-2 missiles being developed by Werner von Braun for the war against England. Zuse always wanted to make his Z-series computers for general use, but still one computer became specialized — the S-1, a variant of the Z-3, which probably supported German military power.

This specialized computer, the S-1, helped the Henschel Aircraft Company produce flying bombs, known as the HS-293. The not so well-known and widely used bomb von Braun HS-293 was an unmanned airplane, worn at the top of the bomber. The bomber pilot caught the target in his field of view and dropped the HS-293, and the bomber crew * radioed its planning to the target. HS-293 blew up Allied troops after August 1943, and also destroyed bridges in Poland during the retreat of the Germans in 1945.

Computer S-1 worked reliably from 1942 to 1944 at the Henschel plant in Berlin, calculated the size of the wing and turn the elevator, important for the HS-293. Workers measured the true dimensions of the wings and elevators; the results of these measurements were placed in S-1, which then calculated the angle of deviation of the HS-293 from the straight path, if these parts were correctly assembled. Zuse developed methods of programming his computer, which did not require a programmer to have a detailed understanding of the internal organization of the computer. He tried to solve a problem that could be called a shortage of the world's leading programmers, because the war was draining human resources. He asked the society of the blind to send him a list of blind people who had shown aptitude in mathematics. From the list, Zuse chose a certain Augustus Fost, who then became a professional in programming.

Now that Z-3 has gained recognition, Zuse wanted to build an even more powerful computer. He imagined it with a large memory of 500 numbers and a 32-bit machine word. Z-4 was Zuse's most sophisticated computer. He could add, multiply, divide or find the square root in 3 seconds. At this time, Zuse already had the support of the German military command for building general-purpose computers, although the Ministry of Aviation, which ordered the computer, was interested in the computer only for calculations related to aircraft design. By 1942, Zuse founded the firm “Zuse Apparatebau”.

He worked alone for most of the war, but by the end of the war 20 employees worked under his leadership. After the German defeat in February 1943 near Stalingrad, Zuse became a staunch supporter of the war to end. His computers could be useful for peaceful purposes. But life was unstable, and he could not be sure whether his cars would remain “alive”. Allies bombed Berlin every day. Z-3 was destroyed, and Z-4 before escaping from Berlin in March 1945, Zuse had to be transported three times around the city in order to avoid bombardment, which disrupted the device’s performance.

Описание Z3

Zuse was allowed to leave Berlin in the last months of the war. In March 1945, he and his assistant transported the dismantled Z-4 by train to Göttingen, 100 miles to the west. By order of the government, his equipment should be taken to underground factories near Northheim, but after the first visit to the concentration camps, Zuse refused. He settled near the mountains in a peaceful Bavarian village. Zuse was offered to leave Germany and move to England or the United States. Then he could build computers for the British during the post-war years. But he stayed in Germany. He lived in Hinterstein until 1946, and his equipment was hidden in the basement of the farm.

In 1946, Zuse moved to another alpine village, Hopferau, near the Austrian border. He lived there for three years. It was time to think. The development of hardware after the war stopped, and Zuse returned to programming.

In 1945, he developed what he called the first programming language for computers. He called the programming system Plankalkul (“calculus of plans”). Zuse wrote a small essay where he spoke about his creation and the possibility of using it to solve problems such as sorting numbers and performing operations in binary arithmetic. After learning how to play chess, Zuse wrote several pieces of programs on Plankalkul, which allowed the computer to evaluate chess positions.

Many ideas of the Plankalkul language remained unknown to a whole generation of programmers. Only in 1972, the work of Zuse was published in its entirety, and this publication made experts think about the impact Plankalkul could have had it been known before. “Apparently, everything could turn out quite differently, but we do not live in the best of worlds,” one scientist remarked on this occasion, criticizing programming languages that appeared later.

In 1948, Professor E. Steyfil from the Technical University in Zurich ordered a Z-4 computer from Zuse for his laboratory. And in 1949, Zuse founded a small company called ZUSE KG, which was to develop computers for scientific purposes. It lasted until 1966, when it was acquired by Siemens AG, but Zuse remained in the new firm as a freelance consultant. In the 1950s and 1960s, Zuse created new computers on the Z-5 and Z-11 relays, then, together with Fromm and Gunch, he created Z-22 on electronic tubes and Z-23 on transistors. One of its latest developments was the Z-25 and Z-31 computers, as well as the Z-64 graphomograph for automatically constructing drawings and maps.

He wrote a book “History of Computing”, published in German and English. In recent years, Zuse lived in the village of Hessian, a few hours drive from Frankfurt, and his favorite occupation was painting, mostly abstract. His work has been on display at numerous exhibitions. He signed some of his paintings with the pseudonym “KONE SEE”. December 18, 1995 Conrad Zuse was gone. His merits, as one of the pioneers of the computer era, are indisputable.

Comments

To leave a comment

Persons

Terms: Persons