Lecture

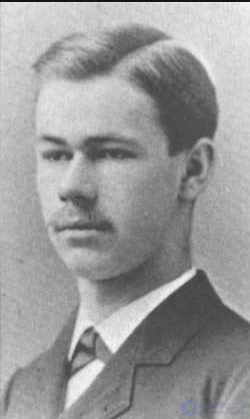

Herman Hollerith is the founder of the counting-perforating technology, the immediate predecessor of modern computers. Being engaged in census data processing in the 80s of the last century, he created a machine that automates the data processing process and invented a data carrier, a punch card, which has not undergone significant changes up to the present time. He was born on February 29, 1860 in Buffalo, New York. Hermann was the seventh child of Johann Hollerith, who emigrated to the USA from Germany in 1848.

After the family moves to New York, Herman enters the school, from which he is soon expelled. (Usually, Herman left the classroom before a spelling lesson. Once, when the teacher locked the door, he jumped out of a window on the second floor, after which he was expelled from school.)

After graduation, Hollerith was taught a Lutheran teacher, with whom he took a course of secondary and high school. At the age of 16, Hollerith entered Columbia College with a specialization in mining.

However, Hollerith was interested, rather, not “by the mining industry”, but by technology, especially electrical engineering. It was in Colombia that he met Professor William P. Trowbridge, who shortly thereafter appointed Hollerith as his assistant at the Statistical Office of the United States Census.

At 19, Hollerith moved to Washington to start his new job. In Georgetown, he became an active member of public circles. He met with Dr. John S. Billings at his home, where he came at the invitation of his daughter. Since Billings was an authoritative expert in analyzing statistical data, he was appointed Director of the Statistical Office for the Census in 1880. It was at this time that Billings informed Hollerith of his idea of creating a punch card machine for compiling tables according to the US census. There are two versions of Billings’s influence on Hollerith’s invention: either he “only proposed to create a similar one”, or he “suggested using cards with a description of a person using marks on the edges of the cards, as well as a device similar to a sorting machine”.

Hollerith himself said the following about this: “I went to Mr. Leland at the Census Office and asked me to hire me to work as clerks. After studying the problem, I went back to Dr. Billings and said that I could work out a way to solve the problem, and then asked if he would work with me. The doctor refused, since he was no longer interested in these problems, except for the data he had received. ”

In 1891, Billings appealed to the American Society for the Advancement of Science: “In 1880, I suggested that various statistical data could be recorded on a single card by punching and then processed by mechanical means, choosing the necessary perforations. The electrical counting machines used now for the population census are the result of this proposal. ”

Billings's daughter said the following: "My father did not have the ability to mechanics, so all the credit belongs to Mr. Hollerith."

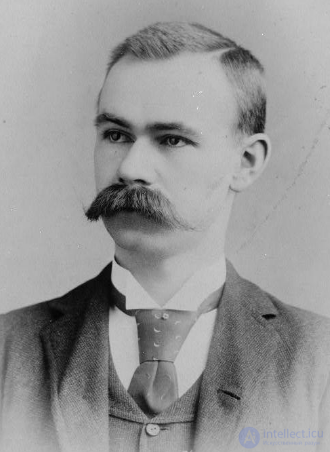

When General F. Walker moved from Washington to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1882, he invited Hollerith to this institute as a teacher of mechanical engineering. Hollerith spent a year there, at the same time developing his ideas and developing the first equipment for recording census data and compiling tables on them. In 1883 he returned to Washington, where he worked in the patent office. Knowledge of patent systems helped him in the next decade as an inventor. In 1884, in St. Louis, he developed the idea of improving the brakes for railway transport. At that time, he could already build a prototype of the tabulator, but He did not have the money for it. It is known that he was unable to borrow money from his family or friends for the needs of his projects, so he built a prototype for his meager savings.

In St. Louis, Hollerith designed electrical brakes for trains and participated in a competition that also featured brakes using compressed air and the vacuum principle. The electric brake was recognized as the best of five, but there were doubts about its practicality (because of the fear of thunderstorms), so this system was rejected, and the patents remained inactive until the end of the term. The winner was George Westinghouse.

The next patent of Hollerith - a device for corrugating metal pipelines - also had no application at first, but later it was used by General Motors to make flexible joints.

Patent 395.782 “The Art of Compiling Statistical Data” became the most significant patent of Hollerith. He was registered on September 23, 1884. Hollerith used his prototype to compile tables on mortality statistics in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1887, and similar statistics for New Jersey. In 1889, New York City mortality data were processed using Hollerith equipment. Thanks to his experience, Hollerith confirmed that punch cards are an essential part of the tabulation process. In 1887, he made a correction in his patent: "It is proposed to improve the method of processing statistical data, which consists of the preliminary preparation of individual punched cards, each of which contains data on one person or object."

As a consequence of this correction, many industrialists had to enter into an agreement with Hollerith on a license for its equipment with punched cards. The following patent No. 397.783 was named “Statistical Device”.

During the 1890 census, data on each person was transferred to 73/8 × 33/4 inch maps. Then did the perforation along the edges, according to each characteristic. One corner of the map was cut diagonally for easy counting and sorting (sampling).

At that time, methods for sorting punched cards were not yet developed, so a similar process was carried out purely visually. For example, the number of a site or area was recorded as a combination of four or five holes located on one edge of the map. Looking through these holes, the inspector could determine: whether there is a punched card in his place, but he could not immediately tell what kind of card it was.

The new Hollerith machine itself made the perforation according to the sample. Since the machine was used for a population census, it was designed to facilitate the work of the operator and reduce the number of errors.

More at that time achieved in the preparation of tables. In the 1880s, electricity was rarely used, so the use of electricity in the computing machine of the time was truly unique.

For his tabulator, Hollerith built a press with a solid rubber plate and guides with an emphasis for cards. The plate consisted of grooves that corresponded to the location of potential perforations on the map. The cups indentations were partially filled with mercury and connected to the back wall of the case with terminals. Above the rubber plate was a box with projection contact points actuated by springs. These points coincided with grooves filled with mercury. When the card was inserted into the press, where the holes appeared on the map, the contact point was in contact with the mercury and the electrical circuit was closed, which triggered the meter. The dial of the counter, capable of registering numbers up to 10,000, was moved one division using an electromagnet, which received a signal through the “mercury cups”. Periodically, the counter data was read and the total figure was manually entered into the final card.

Maps could be sorted according to the perforation characteristic. The device was equipped with a box with 24 compartments. Each compartment had a lid, which was opened with a spring when a card entered there. After selecting a card, the lid was opened and the card was manually picked up and folded into the right place. Only 14 years later, Hollerith invented a fully automatic sorting system.

To control accuracy, the following measures were taken:

If several results were summarized at once, then each passing card was recorded on the dial, and it was possible to check the final figure by summing up the intermediate results;

Hollerith was widely known for his work, but in 1890 his success was completely unforeseen when he signed a contract for 11 population censuses after winning a census competition in four St. Louis districts with more than 10,491 inhabitants.

Hollerith's method was not only the fastest, but also the most accurate. It was estimated that Hollerith saved the state $ 597,125. During the census, it was again calculated that he saved two years and a large amount of money.

In 1890, Hollerith turned 30 years old. He received the title of Ph.D., was world famous for his invention of the tabulator and punched cards, and also entered into a very important contract with the US Census Bureau. It seemed that his financial and professional future was secured. On September 15, 1890, he married Lucia Giverli Talcott, the daughter of his doctor from Washington. They lived happily for 39 years and had three sons and three daughters. During the honeymoon in Austria, Hollerith agreed with the Austrian government on the use of his invention at the Central Bureau of Statistics. So began his international career.

Initially, Hollerith managed the Hollerith Electric Table Making Company and a workshop in Washington, where computers were assembled and repaired, and also punched cards were made. Hollerith discovered that industry-issued maps were too soft for his machines: the paper exfoliated and clogged the grooves with mercury. It was necessary to improve the quality of the paper, and he himself began to make it. If used improperly, the machine could fail, so in order to avoid false rumors about the poor quality of the machines, Hollerith repaired or replaced the failed parts. Thus, in the trade agreement appeared item on the maintenance of machines.

By 1895, Hollerith’s cars were already working in Austria, Canada, and negotiations were underway to sell them to Italy and Russia. Later his computers were used in other foreign countries.

But troubles soon began. The census bureau became displeased with Hollerith’s financial demands, and Hollerith didn’t want to change his car. As a result, the Census Bureau began producing its computers, relying mainly on past employees of Hollerith, who disclosed their know-how. The bureau borrowed the ideas of Hollerith and replaced some mechanical parts with electrical mechanisms. Supervised the creation of new machines, James Power. He introduced 300 new punchers for the 1910 census. This was the beginning of an organization called the Powers Computing Company, which in 1927 merged with Remington Rand (in 1955 by Sperry Rand Corporation).

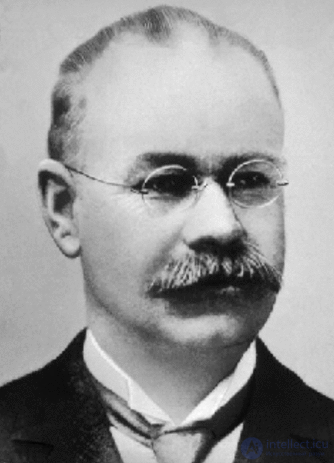

Fears of losing the contract with the Census Bureau forced Hollerith to seek new markets for their systems in the early 1900s. By 1910, numerous insurance companies, railways, department stores, factories, energy companies, etc. were on his client list.

Despite his success and wealth, Hollerith remained a man of principle. He felt that the director of the Census Bureau behaved dishonestly when ordered to make changes in the Hollerith machines intended for the 1900 census. 20 special machines were sold to the bureau. Hollerith felt so confident that he sued the US government, but failed in this matter. Thus, in his 50 years, despite his success, he had to put up with the bitterness of defeat and the false testimony of his “friends”.

In 1911, the world famous entrepreneur Charles Flint, who formed many industrial empires, became interested in the Hollerith business. He formed one of the three companies - Computer-Tabulating-Recording Co.

When registering, an interesting note was made in the note: the production and sale of cards increased to 1 million per day, and the annual income continued to increase. Hollerith paid $ 2 million for his stake in the company and made a ten-year consultation contract worth $ 25,000 a year, thereby promising not to organize a competing firm. In the first years of its existence, the new company did not succeed very well. In 1915, Thomas J. Watson, Sr., was appointed President and CEO.

The merits of Watson and the unprecedented success of the company (since 1924 - IBM) have now become a legend. During the years 1911–1921, Hollerith continued to invent and obtain patents, but with Thomas Watson they were not friends. Assistant Hollerith - Otto Brightmeier, who started working with him in the last century, gained favor and soon became the responsible vice president of IBM. The competing company was Remington-Rand, which became IBM’s leading data processing company after IBM.

Most of all, Hollerith loved to engage in family life, eat deliciously, build houses, raise livestock, buy cars, and give gifts to friends and neighbors. In his youth, Hollerith said that if he had money, he would have a wine cellar and a yacht. In 1911, he bought a yacht. He also had a wine cellar, but doctors forbade him to drink because of high blood pressure. He enjoyed cars. In 1896, Hollerith had one of the first electric cars. In 1905 he had Waltham Orient. Sometimes he had several cars at once. In 1908, his family moved to Rockville (Maryland, an estate of 10 acres), and later - in Taydwater (Va.), In an estate with 230 acres of land, where Hollerith raised cattle and gave bulls to their neighbors to improve livestock.

Hollerith enjoyed farming and animal husbandry. He also caught oysters and West European herring in the bay, on the bank of which his farm was located. He sent everything he mined and hand-made to his friends as gifts. He bought various electrical appliances (irons, washing machines, refrigerators) that went on sale, and made power supplies for them. He had many boats, but he abandoned his yacht with the Norwegian crew before the First World War, which prevented him from making an ocean cruise. In 1915, he completed work on his home in Georgetown and home for his two daughters. It is said that if Hollerith invested $ 1 million into the CTR fund in 1914 and left it there, now the amount would be $ 2 billion.

Herman Hollerith died at home in Washington from a heart attack on November 17, 1929, at the age of 69, in the year of the collapse of the Stock Exchange, not knowing and not regretting the lost opportunities. Hollerith ended his nearly seventy-year life in a luxurious, happy old age, surrounded by a loving family. Until his last days, he hated spelling rules to such an extent that he allowed himself to write the word “statistician” as he pleased.

When Hollerith built a machine to compile the 1890 census tables, he probably didn’t think about the full depth of the data processing problems we are dealing with and which belong to the science of computer science. But in no case can one deny the great importance of the ideas embodied in the inventions of Hollerith. His car was not only computing; she performed selective sorting, which is the basis of any information retrieval. Perhaps it is the simplicity with which Hollerith approached the solution of these problems, and is his most important contribution to computer science. He used the most advanced technique of his time, but his methods were easy to understand, highly efficient, productive, and time-tested.

Comments

To leave a comment

Persons

Terms: Persons