Lecture

Subjunctive words “if only” are related to the life and work of Charles Babbage. If only he would go a little further, if only he would create amazing machines that he painted in his projects. What could be? Howard I-ken, who built one of the first computers, once remarked that if Babbage lived 75 years later, the inventor of the 19th century could eclipse his fame. Such assumptions are always baseless, and yet there is some terrible injustice - Charles Babbage was so far-sighted and so ahead of his time! Babbage lived at a time when existing technologies made it difficult for a computer designer to implement his ideas. Therefore, Babbage has not created a computer. After his death, the world had to wait for this invention for about 70 years. And yet his computer scheme was so close to the goal that Babbage became an integral part of the early history of computers. He is rightly called the forerunner of the computer age.

If the truth is that the level of technology of the XIX century did not allow to create the accuracy necessary to build the Babbage machines, then this is equivalent to the fact that he was obsessed with the sense of perfection that made him unable to complete one project before starting another. Consequently, it is possible to blame Babbage himself, as well as the lack of technology, because he did not reach the end in creating a digital computer. Forgotten for decades after his death in 1871, Babbage received recognition for his work only in the 40s of the 20th century with the beginning of the computer era.

If he had visited our era, he would have been very surprised to find out how widely computers are used. And yet, it would have cost him only to look inside any standard computer, his surprise diminished. He might have been stunned by the use of electronic technology, but he would have been struck by the basic principles of the central processor and memory.

Babbage was one of the greatest inventors of the XIX century. He did so many things and did them so extremely well. He was a mathematician, an engineer, and most of all a computer designer. As if in one person there were ten different faces.

In 1822, he designed the differential machine, considered by some to be the first automatic computing device. Only a decade later, in 1834, he began designing his analytical machine. If something concrete had arisen, it could successfully become the first universal computer. But the actual machine was not built, so its claims for glory remained largely only on carefully designed drawings. Nevertheless, Charles Babbage achieved fame, being the first to grasp the general concept of a computer. Almost all of the principles underlying today's computer were inherited from an astute nineteenth-century scientist. Babbage's analytical machine was designed to solve any mathematical problems. Most importantly, the machine also provided for several features (conditional transfer of control, subroutines, and cycles) that could make it programmable. Punch cards, data transmission medium, which ultimately found their place in the computer, were used to enter programs.

Babbage was born on December 26, 1791, in the place where the small town of Southwark, a suburb of London, is now located. He was a weak, sickly child with strong curiosity and an imaginative mind. When he was given a toy, he broke it apart to find out how it was designed. Once he made two hinged boards that gave him the opportunity to walk on water. Babbage early showed a penchant for mathematics, possibly inherited from his father, a banker. His children's enthusiasm was directed at the supernatural. Once he tried to establish contact with the devil, puncturing a finger in order to receive a drop of blood, and then, having read a prayer to God, backwards; Babbage was disappointed to find that the devil did not appear. His interest in the occult continued. He made an agreement with a childhood friend that one of them will die first, will appear before the surviving party to the agreement. When a friend died at the age of 18, Babbage stood all night waiting for the ghost to appear - just to find that his friend did not take his role in this deal seriously. Studying in college, Babbage founded a ghost club to gather information on a supernatural phenomenon.

In October 1810, Babbage entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied mathematics and chemistry. His teachers were disappointed when Babbage decided that his knowledge exceeded them. The mathematics of Newton, who died 200 years ago, still retained her influence in Cambridge, despite the new ideas circulating in Europe. Babbage and his friends created a club called the “Analytical Society”, promising each other to do everything in their power to make the world wiser than it was before them. Society helped revive the study of mathematics in England, focusing on the abstract nature of algebra and trying to bring new ideas.

Babbage considered joining the church, but rejected the choice, finding a lack of money for it. He thought of mining as a potentially profitable venture, but abandoned the idea.

On July 2, 1814, he married Georgiana Whitmore. In the period from 1815 to 1820, Babbage became very interested in mathematics. He studied algebra and wrote scientific articles on the theory of functions. Since he was a liberal, during the rule of the Conservatives, Babbage was unable to obtain patronage that would ensure him a well-paid position. There were several vacancies for professors, but his attempts to get a professorship were unsuccessful. Georgiana Babbage gave birth to eight children over 13 years, three sons survived to adulthood. Babbage insisted that his wife take care of them and educate them so that he could be free and do his research.

Being a convinced eclectic, Babbage took up a long study of how to make life more appropriate. He was considering a cheaper way to ship parcels for postal agencies. He plunged into the depths of the ocean in a diving bell to learn scuba diving. His inquisitive mind led him to test the ability for a person to walk on water - the answer was negative.

He also entered the oven to determine the effect of a temperature of 256 degrees Fahrenheit. He quickly left the oven, receiving minor burns. Babbage was a prolific writer who published 80 books and articles in various fields, such as mathematics and theology, astronomy and management. His book “The Economics of Machinery and Production”, written in 1832, was called the first attempt at production research. The main theses of the book are that industry requires a scientific approach. The ability to statistics instigated him, perhaps only for fun, to calculate the chances of biblical miracles: the one resurrected from the dead was in a ratio of no more than one in ten to 12 degrees! In addition to the undisputed title of the grandfather of a modern computer, Babbage was a major inventor.

One of his inventions was the “mysterious” beacon in which the light flashes and goes out; This system is used today worldwide. Another invention was the ophthalmoscope, which doctors still use to examine the inside of the eye. Babbage invented railroad cars equipped with instruments used by British conductors to measure pressure when the train was moving. This is thanks to Babbage, the British railways have a broad gauge. He was also an eminent coder of his time, using a mathematical apparatus for decryption.

This activity brought him great pleasure. He had a predominant characteristic - the pursuit of perfection. The scientist moved from task to task with the persistence that gave rise to flashes of genius. But he was too impatient to allow himself time to translate these flashes into concrete reality. However, he was always accurate. After reading Tennyson's lines from “The Vision of Sin”: “Every minute a man dies, every minute is born,” he wrote to the poet: “Obviously, if it were true, then the population would stand dead center.” He suggested the following: “Every moment a man dies and 1 and 1/16 is born.” Tennyson seems to have caught the point, because he changed the lines to “Every moment a man dies, every moment is born.”

The most significant contribution by Charles Babbage was made in the field of mechanical computing, although the recognition came a long time after his death. Striving for perfection, Babbage highly appreciated accuracy and saw the need to improve the mechanical calculators of his time. Primitive and manual, they not only worked slowly, but were prone to mistakes. Due to negligence, errors were encountered in large numbers in astronomical charts and navigation tables, errors that led to tragic shipwrecks. Babbage tried to invent such a machine that could perform two operations: calculate and print mathematical tables, thereby avoiding the errors that occur between the handwritten copy and the printed version.

One evening, when half-asleep Babbage was looking at a table of logarithms in the room of the Analytical Society, another member of the society approached him and asked what he was dreaming about. Looking up, Babbage replied that he was thinking about the possibility of finding a way to calculate all the tables on the machine. This short, rather insignificant conversation became a turning point in the early history of computers. Babbage decided to use all his time in order to get closer to his goal - automating the calculation of mathematical tables. By 1822, he designed what he called the difference machine, a small device for calculating tables that are important for navigation.

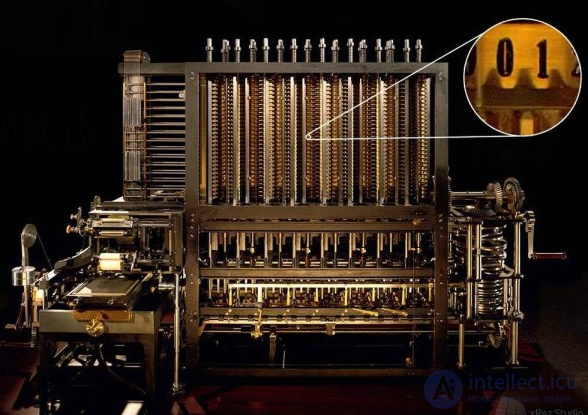

Babbage created a small working model. She could control six-digit numbers and express in numbers any function that had a constant second difference. Then, on June 14, 1822, speaking before the Royal Astronomical Society, he proposed the creation of a large, life-size difference machine, the first automatic computing device. His scientific report to the public, entitled “Observing the Application of Machinery to the Calculation of Mathematical Tables,” was well received. “All arithmetic was now taking place inside a mechanism capable of quick perception,” he wrote later.

This report was the very first mechanical calculation report. Babbage imagined a machine that could do numerous calculations automatically. When the machine starts to work, the operator will perform the work of the observer. As Babbage proclaimed in a letter to the President of the Royal Society, Sir Humphrey Devi, people are now free from the “intolerable work and tiring monotony” of mathematical calculations; instead, machines using “gravitational or any other driving force” could easily replace human intelligence.

The differential machine would be supplied with a power engine using a falling weight lifted by a steam engine. According to one version, the Babbage machine would print numbers with 18 characters. There would be no more typographical errors, because the tables would be printed directly from the metal plates of the machine.

By July 1823, Babbage had obtained the consent of the Chancellor of the Treasury to give him 1,500 pounds, which was much less than required, but, nevertheless, a decent amount. This was enough to support Babbage in the belief that he had enlisted the support of the official patron for the necessary time, which was a mistaken opinion on his part.

The Difference Machine was the largest government-funded project of the time, presumably because government officials were interested in promising more accurate navigation and artillery tables. Ultimately, Babbage invested from 3,000 to 5,000 pounds from his own pocket, suggesting that in time the government would reimburse him for the costs. He found the outstanding instrumental master of England, Joseph Clement, who in turn took the best workers in the country.

Babbage hoped to build a working car in two or three years, but soon found that it was too optimistic. Gathering together the parts that would give him the opportunity to create parts of the car turned out to be much more difficult than expected. The next few years, he designed the machine parts, and then tried to build a machine that would make the parts themselves. It was a tedious and futile job that did not produce the desired results, although it contributed to the development of British instrumental skill. At times, it seemed that Babbage was his own enemy.

His obsession with perfection pushed him to numerous changes in the drawings. Workers had to reinvent new parts, delaying the project. His youngest son Charles died in June 1827, his wife in August of the same year. Babbage shifted the care of the surviving children to his mother. He never married again. The next year, Babbage spent abroad.

Although he inherited £ 100,000 from his father and received an additional £ 1,500 from the government, financial affairs continued to harass Babbage. He invested his own money; friends donated £ 6,000. Nevertheless, it took 20 years after he conceived the differential machine, and it remained unfinished, while Babbage and the British government were in conflict over the property of the invention.

On the one hand, the process of creating the difference machine was slowed down due to disagreements between Babbage and Clement. Clement always thought that it was difficult to work with Babbage, but another problem arose when Babbage decided to move the workshop closer to his home (Clement's workshop was 4 miles away). When Babbage asked Clement to move with tools and drawings to a new workshop, the latter refused. He was not attracted by the prospect of being forced to divide his time and energy between the two work addresses. Babbage was in a quandary. He had no desire to pay Clement from his own pocket, but he understood that Clement’s absence would have meant the suspension of the project. Babbage was economical, so all work on the differential machine was stopped in 1833.

Around the same time, the Swedish technical editor Georg Schütz, after reading about the device in the Edinburgh Review, attempted to build a difference machine similar to the Babbage machine. Soon, his son, engineer Edward, joined the project. Unable to enlist the support of the Swedish government, the two continued on their own, creating by 1840 a small machine that could perform operations with first-order differences.

Over the next few years, they expanded the machine to three orders of magnitude difference and created a printing device. By 1853, they had their own “table machine”, as they called it, which could perform operations with fourth-order differences, process 15-digit numbers and print the results. She figured out much faster than any person, and presented the first real proof that the machines can be used in operations with numbers.

In 1854, the Shüttsev family showed their invention to the Royal Society in London, receiving the support of Charles Babbage himself. At the big exhibition in Paris the following year, the tabular machine won a gold medal, in part due to the attempts of Babbage's influence on commissioners. Awarded a gold medal, the family was able to sell the car for $ 5,000 to Dr. Benjamin Gould, director of the Dudlin Observatory in Albany, New York. Dr. Gould used it to calculate a series of tables related to the orbit of the planet Mars. However, despite all the accuracy of machine computing, in 1859, Dr. Gould was fired! The table machine was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution. A copy of the device was built in the late 50s of the XIX century by the British magazine “Register General”.

Schütz’s machine did not always function correctly. The existence of this simpler version of the Babbage machine suggests that the lack of technology can not be the only reason for the inability of Babbage to create their cars.

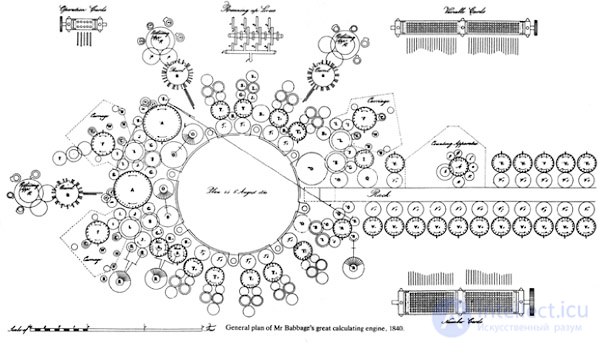

Deprived of his tools and drawings (Clement appropriated them after a dispute in 1833) Babbage decided to develop a project for a completely different machine that would be easier to manufacture than a differential one. He began in 1834 and over the next two years created the basic elements of a modern computer. Even before the creation of the difference machine, Babbage understood its shortcomings.

Essentially it was a special purpose calculator, and the computer should be not only convenient, but also universal, capable of performing any arithmetic or logical operation. Babbage called this more complex device “analytical machine”. If he had succeeded in its creation, it would be the first universal computer. It is also important that the analytical machine was conceived as programmable, so its commands were modifiable. Babbage wrote that he was surprised by the power that he was able to give to the car, forgetting that he still had to build it. His biographer, Anthony Heyman, called the analytical machine one of the most important intellectual achievements.

Babbage's ideas are now surprising by their similarity to the general concepts of modern computers. The instructions were to be entered into an analytical machine with the help of punched cards, then stored in a warehouse, essentially in the memory of a modern computer. The idea of punched cards was borrowed from the then-revolutionary Jacquard loom, which used hole cards to automatically control the threads passing above or below the moving shuttle. Babbage used cards with holes for quick command entry.

Unfortunately, he never achieved the ultimate goal in the nature of a modern computer. First, he was only thinking about mechanical devices, the idea of electricity, apparently, had never crossed his mind. He also did not imagine a team that has two parts: operational and address. Babbage pondered a lot of number systems for the analytical machine, but settled on decimal. The numbers should have been kept in memory. He wanted to put on wheels on 10 different positions of numbers.

The numbers had to be transmitted using a system of levers to the central unit. The control of the whole process was carried out with the help of several punched cards, which accurately determined the operation and provided the address with the action object in memory. When commands were placed on operational cards, the device corresponding to the central processor of a modern computer received information and performed the operation.

One arithmetic operation completed in a second. The results were then sent to memory. The final results were printed out - this action was performed automatically. Babbage assumed that the storage capacity would be 1000 fifty-digit numbers. Having explored many options for performing four arithmetic operations, he invented the concept of proactive transfer. It was much faster than the sequential transfer from one rank to another. Babbage also invented a parallel transfer, with which a whole series of additions could be performed with a single transfer operation at the end. The analytical machine required six steam engines to power the power engines, which produced a lot of noise.

Современники Чарльза Бэббиджа могли не узнать о достижениях изобретателя, если бы не старания Ады, графини Лавлейс, дочери поэта лорда Байрона. Бэббидж встретил ее впервые на вечеринке, которую он давал 5 июня 1833 года. Ей тогда было 17 лет. 9 лет спустя в Италии итальянский военный инженер, Луиджи Федерико Менабреа, описал математические принципы Аналитической машины в научной статье. В 1843 году Ада Лавлейс выполнила английский перевод научной статьи Менабреа, сопроводив ее обширными примечаниями. Этот перевод дал Англии первое небольшое представление о достижениях Бэббиджа в области компьютеров.

Настоящие заметки оцениваются как один из главных документов в истории компьютеров. Ада писала: “Мы можем с большой уверенностью сказать, что аналитическая машина плела алгебраические модели точно так же, как и ткацкий станок Жаккара ткал цветы и листья”. Для Бэббиджа Ада и ее муж, граф Лавлейс, стали друзьями на всю жизнь, а Ада, кроме того, стала общественным адвокатом Бэббиджа.

Только в возрасте 71 года Бэббидж был готов предать гласности свои идеи. Его первая разностная машина демонстрировалась в Лондонском научном музее, и Бэббидж был рядом, чтобы объяснить ее действие. В последние годы жизни Бэббидж был бодрым, с постоянным желанием похвастать своей мастерской.

On the evening of October 18, 1871, two months before his eightieth birthday, Charles Babbage died. Only a few people attended the funeral, which indicated a lack of interest in his work on the part of his contemporaries.

Comments

To leave a comment

Persons

Terms: Persons