Lecture

Informing dialogue, experiments, games, exercises, situation analysis, development and development of specific skills.

So, according to our classification, there are five kinds of questions: closed, open, critical, rhetorical, questions to think about. Note that open and closed questions are highlighted in almost all types of classifications. This fact makes them essential.

The most common questions are divided into open, closed, encouraging, indirect or implied, as well as projective questions.

Now we will consider each type in more detail, and also we will give examples.

Open questions are those that require a detailed answer and some explanation. They can not be answered either "yes" or "no." Such questions begin with the following interrogative words: “how”, “who”, “what”, “why”, “how much”, “which”, etc.

Such questions allow your interlocutor to choose the information to answer at their discretion. On the one hand, this may lead to the fact that the interlocutor will hide what he does not wish to disclose. But on the other hand, if you ask a question in a suitable emotional situation, the interlocutor can open up and tell a lot more than the question you asked.

Open questions allow you to turn your monologue into a conversation. However, there is a danger that you lose control of the conversation, and it will not be easy to regain control.

Let us give examples of such questions:

Questions of a closed type are such, when answered, you can answer either "yes" or "no." Often in closed questions the particle "li" is used. They limit the interlocutor’s freedom as much as possible, leading him to a monosyllabic answer.

By asking this kind of questions, you can keep the conversation under your control. However, the interlocutor cannot express his opinion or share ideas.

In addition, closed questions have a number of negative features:

Closed questions are recommended when you need to gather a lot of information in a short time. For example, when conducting various studies. If you plan to get to know your interlocutor better and assume that your acquaintance will continue, you should alternate closed questions with open questions, allowing your partner to speak.

Examples:

We continue to consider the types of questions. The next step is a rhetorical question that serves for in-depth and detailed consideration of the subject of conversation. Such questions can not be given a definite and unbiased answer. Their goal is to indicate unresolved problems and raise new questions or to raise the support of your opinion by the participants of the discussion by tacit consent. In formulating such questions, the “li” particle is also often used.

Examples:

Another major type of issue is the turning point. These are questions that help keep the discussion in a certain direction. They can also serve to raise new problems. They are asked in those situations when you have received comprehensive information on the problem under consideration and would like to switch the audience’s attention to another one, or when your opponent’s resistance has arisen and you want to overcome it.

The interlocutor's answers to such questions allow finding out the vulnerable moments in his judgments.

Examples:

These kinds of questions encourage the interviewee to ponder and think carefully about what was said earlier and prepare comments. In such a speech situation, the interlocutor gets the opportunity to make his own changes to the position already stated by someone. This allows you to look at the problem from several sides.

Examples of such questions:

Thus, we examined the meaning and examples of the types of questions used in the Russian language.

There are also several types of questions in English. There are five of them, as in Russian. The use of questions will depend on the situation, context and the purpose for which you are asking them. So, consider the types of questions in English with examples.

Common questions are identical to closed ones in Russian, that is, they imply a simple answer: “yes” or “no.” Serve for general information only.

Such questions are compiled without question words, but begin with auxiliary verbs. And as you remember, in English for each tense there are certain auxiliary verbs.

The word order in the preparation of the question: auxiliary verb - subject - semantic verb - addition - definition.

Examples:

We continue to consider types of questions in English with examples. Separating this type is called because it consists of two parts, which are separated by a comma:

The “stub” is usually the opposite of a statement. That is the purpose of the question - to verify the authenticity of the statement.

Examples:

Types of questions can also serve for more information. For example, a special question. He necessarily begins with question words. The following are commonly used: when, why, where, which, how , etc. These are not what and who when they play the role of subject.

Thus, the question has the following structure: question word - auxiliary verb - subject - semantic verb - addition.

Examples:

Similar questions suggest a choice between two different answers. The word order here is the same as in the general question, but it is necessary to offer an alternative opportunity.

Examples:

This type is used when it is necessary to ask a question to the subject in the proposal. It will begin with the words what or who . The main feature of this type of questions is that the order of words in its formulation remains the same as in the statement. That is, the word order will be: who / what - semantic verb - addition.

Here are some examples:

So, we have considered the possible types of questions in both Russian and English. As can be seen, in both languages, despite the huge difference in origin and grammar between them, the questions perform approximately the same functions. This tells us that the conversation in any languages is conducted with specific goals. Moreover, the mechanisms for controlling the course of reasoning, governed by questions, also appear to be similar.

Open questions

Open questions encourage the client to verbal activity. By definition, open-ended questions require a relatively comprehensive, not one complex answer; they cannot be answered simply by “yes” or “no”. Usually such questions begin with a question word like or what. In the literature, open questions sometimes include questions that begin with question words where , when , why and who , but such questions are more correctly considered only partially open, because they do not stimulate conversation as effectively as interrogative sentences with how or what (Cormier & Nurius, 2003; Hutchins & Cole, 1997). In the following hypothetical dialogue, questions that relate to open ones are used predominantly.

Interviewer: When did you first get panic reactions? Client: In 1996, if I'm not mistaken.

Interviewer: Where were you during the first panic attack? Client: I was just getting into a subway car in New York. Interviewer: And what happened?

Client: When I entered the car, my heart began to pound like a hammer. I thought I was going to die. I struggled to grab the metal rail next to the seat, because it seemed to me that I would fall down and would laugh at me.

Interviewer: Who were you with? Client: With no one.

Interviewer: Why didn't you try again to use the subway? Client: Because I was afraid that the panic attack would happen again.

Interviewer: How do you feel about the fact that your fear of panic attacks imposes such restrictions on you?

Client: Well, actually, not very well. I'm more and more afraid to go somewhere else. I am afraid that soon because of this fear, I will completely stop going out.

As you can see, the questions that are called open differ in their degree of openness. Not all of them contribute to the client’s deep and comprehensive self-disclosure. Questions beginning with what and how usually determine the most thoughtful answers of the client, but not always. More often, the specificity or breadth of the answer is determined by how the question is formulated or how. For example, the question “How do you feel?” Or “What did you do that evening?” Is usually followed by a very

concise answers. The openness of a particular question should be judged primarily by the answer to it.

Questions why are unique in the sense that they force the client to take a defensive position. S. Meyer and S. Davis argue: “Questions, first of all the question why , force customers to resist and encourage them to explain their behavior” ( Meier & Davis, 2001, p. 23). Why do people usually ask for one of two reactions. First, customers respond: “Because ...”, then they continue to explain, sometimes very detailed and rational, why they think, feel or act in a certain way. second, some clients are defended with the question “Why not?” or, if they perceive the question why as aggression, go to the counteroffensive: “Why, why not?” This shows why clinicians try to use questions why less often - they cause resistance and obstvuyut intellektua tion of, impaired emotional contact. On the other hand, in those cases when there is a stable mutual understanding and you want to get the client to comprehend or translate a certain aspect of his life into an intellectual plan, the questions why may be appropriate. They can help the client pay closer attention and better understand some patterns or motives of their behavior.

Closed questions

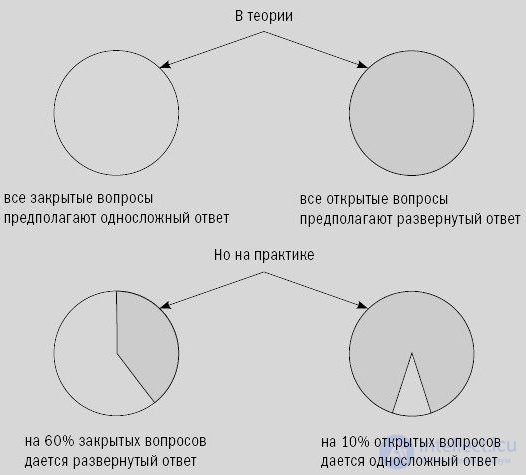

Closed questions usually imply a “yes” or “no” answer (Hatchins & Cole, 1997). Although the questions that begin with the words “ who , where, or when” are considered open to some, in fact they imply a strictly definite answer, therefore we consider that they should also be considered closed (see the box “From theory to practice 4.1” ).

Closed questions limit the client’s verbal expression and lead to more specific answers than open questions. They can perform the function of reducing or controlling the verbal activity of the client. Reducing verbal activity is useful if the client talks too much during the interview. In addition, guiding a client to a specific way of describing his or her experience at a tomer may be useful when conducting diagnostic interviews (in the example of a panic attack in the subway, the interviewer might ask: “Did you feel dizzy?” to cure the presence of symptoms associated with panic reactions).

Open and closed questions

The four pairs of questions below are designed to obtain information related to the same topic. Imagine how you would answer these questions, and then compare your options with the responses of colleagues.

1. (Open ) “How do you feel about going through psychotherapy?”

( Closed ) “Are you okay about going through psychotherapy?”

2. ( Open ) “What happened after you entered the subway and felt a heartbeat?”

( Closed ) “When you entered the subway, did you feel dizzy?”

3. ( Open ) “How did you perceive your meeting with your father after so many years of enmity with him?”

( Closed ) “Were you happy to meet your father after so many years of enmity with him?”

4. ( Open ) “How do you feel?” ( Closed ) “Are you angry?”

Mark and discuss with colleagues the difference in how you (and customers) respond to open and closed questions.

Sometimes clinicians unintentionally or intentionally transform open-ended questions into closed ones with clarification. For example, you can often hear how students build the following interrogative constructions: “How did you perceive the meeting with your father after so many years of enmity with him — were you glad?”

As you can see, the transformation of open questions into closed extremely limits the answer of the client. If only clients who are asked such questions are not particularly expressive or assertive, do they respond in the way the clinical interviewer “prompted” them, not thinking about fear, relief, dissatisfaction, or any other feelings that they might have meeting

Closed questions of a general nature do not contain special question words. Such constructions can be useful if you want to get some specific information. Closed questions are traditionally used closer to the end of a clinical interview, when emotional contact is already established, time is short, and the viewer needs effective questions and concise answers ( Morrison , 1994).

If you start an interview with the frequent use of non-directive clicks, but later change the style to get more specific information using closed questions, it will be useful to notify the client about a new interview strategy. For example, you can say: “Well, we still have about 15 minutes, and there are a few things that we definitely need to talk about, so I will ask you very specific questions.”

Prompting questions

You can also answer one-word questions “yes” or “no”, but they are designed to launch a deeper analysis of the client’s feelings, thoughts or problems (Shea, 1998). In a sense, prompting questions reveal the desire or unwillingness of the client to respond to them. Questions of this type usually begin with polite formulas. Could you ... Would you like to ... etc. For example.

“Could you tell us about how you felt when you discovered AIDS?”

“Could you describe the reaction of your parents if they found out about your sexual orientation?”

“Would you like to tell more about this?”

“Could you tell us about what happened last night during your quarrel?”

А. Айви считает побуждающие вопросы самыми открытыми среди прочих типов: “Вопросы наподобие Не могли бы вы... считаются максимально откры тыми и обладают некоторыми преимуществами закрытых вопросов в том, что клиент волен сказать: “Нет, я не хочу об этом говорить”. Вопросы типа Не мог ли бы вы... означают меньший контроль и власть, чем другие” (Ivey, 1993, р. 56).

Чтобы побуждающие вопросы достигали цели, при их применении необ ходимо следовать двум основным правилам. Во-первых,желательно не зада вать побуждающие вопросы в случае, если необходимый контакт с клиентом еще не установлен (Shea, 1998), поскольку в этом случае побуждающие во просы могут быть восприняты клиентом как закрытые (т.е. клиент ответит смущенным или враждебным “да” или “нет”, и контакт может нарушиться).Во-вторых,лучше избегать подобных вопросов при клиническом интервьюи ровании детей и подростков, поскольку они зачастую понимают побуждаю щие вопросы буквально и могут ответить отрицательно (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 1997). For example, if you ask a child: “Would you like to tell me how you felt when dad left you?”, He can answer: “No!”, Which, of course, does not contribute to the success of a clinical interview and puts you in a quandary.

Indirect questions

Indirect questions often begin with the words interesting , must be or probably ( Benjamin , 1981, p. 75). They are used in situations where the interviewer wants to know the thoughts or feelings of his client, but does not intend to exert pressure on him. Here are some examples of indirect questions.

“I wonder what feelings you have in connection with the upcoming wedding?”

“I wonder what you are going to do after you graduate?” “I wonder if you thought about finding a job?” “Perhaps you have your own opinion regarding your parents' divorce?”

“It must be difficult for you to get used to disability?”

Indirect issues, if abused, may seem tricky or manipulative to the client. Therefore, they should be asked only from time to time, usually after establishing appropriate emotional contact with the client.

Projective questions

Projective questions help the client to identify, formulate, analyze and clarify unconscious or unclear conflicts, values, thoughts and feelings. Projective questions begin with different variations of the formula What ... if ... and invite the client to think. Often, projective questions are used to stimulate the imagination and help the client to analyze the thoughts, feelings and behaviors that would occur in certain situations. For example.

“What would you do if you were given a million dollars without setting any conditions?”

“If you were offered to fulfill three of your every wish, what would you wish for?”

“If you needed help or were very scared, or if you were desperate for money, who would you turn to?”

“If you could turn back time and change the events of that evening (or any other important event), what would you do differently?”

Projective questions can also be used to evaluate customer judgments and values. For example, an interviewer can analyze the answer to the question “How would you dispose of a million dollars?” In order to judge about the values and prudence of the client indirectly. With the help of the million dollar question, one can also diagnose the process of making decisions by the client and the features of his judgments. Projective questions are often used in the study of mental status.

Therapists differ in their use of questions. Some of our students spoke about the use of questions during a clinical interview.

“I felt more confident than the interviewee.” “I felt I was in better control of the situation.”

“I felt more tension.”

“It was hard to think about questions while I was trying to listen to a client, and it was difficult to listen to a client while I was thinking about questions that I could ask him.”

“I thought I was impatient. I always wanted to kill a client and ask questions. ”

“I did not feel the tension. I really enjoyed asking questions! ”

It is obvious that questions cause certain reactions - both in the interviewer and in his client. It is very important to understand these reactions. Some of them are unique and individual for each person, others are more common and universal. Unfortunately, it is often difficult to find a balance between our own need to ask (or not to ask) and the need of clients to be (or not to be) asked.

Применение вопросов, как правило, дает несколько позитивных резуль татов. Открытые вопросы могут подвести клиента к более углубленному об суждению своих мыслей и чувств. Закрытые вопросы могут помочь интервьюеру заострить внимание клиента на определенной информации, доступ к которой по другим каналам затруднен. Когда интервьюер принимает на себя руководящую роль и контролирует интервью с помощью вопросов, некоторые клиенты чувствуют облегчение. Вопросы также могут помочь разъяснить или уточнить смысл сказанного клиентом. Вопросы — эффек тивный инструмент для выявления специфических, конкретных примеров поведения клиента. Правильное применение вопросов — важная состав ляющая диагностического интервью (см. табл. 4.1).

Применение вопросов может привести и к негативным результатам. В вопросах проявляются интересы и ценности интервьюера, а не клиента. Соответственно, клиенты могут подумать, что их собственная точка зрения не важна. Конечно, компетентные интервьюеры могут снизить этот риск до минимума, спрашивая клиента о том, что он сам считает важным, напри мер: “Что еще, по вашему мнению, нам нужно сегодня обсудить?” Вопро сы, кроме того, ставят клинициста в положение эксперта, который должен

задавать нужные вопросы и иногда знать правильные ответы. Злоупотреб ление вопросами подчеркивает аспекты власти, ответственности и автори тета, присущие ситуациям клинического интервьюирования.

Table 4.1. Классификация вопросов

Слова, с которых начинается вопрос

“Что”

“Как”

“Почему”, “зачем”

“Где”

“Когда”

“Кто”

“Были ли вы...”, “Участвовали ли вы.••»» “Полагаете ли вы...” и т.п.

“Не могли бы вы...”, “Не хотели бы вы...'

“Интересно...”,

“Должно быть, вы...

“Что... если бы...”

|

Тип вопроса |

Обычный ответ клиента |

|

Открытый |

Информация констатирующего |

|

|

характера об определенном фактаже |

|

Открытый |

Информация о процессах и |

|

|

последовательности действий (событий) |

|

Частично |

Объяснение или защитная реакция |

|

open |

(оправдание, вербальная агрессия и т.п.) |

|

Минимально |

Информация об определенном месте |

|

open |

|

|

Минимально |

Информация об определенном времени |

|

open |

|

|

Минимально |

Информация об определенном человеке |

|

open |

|

|

Закрытый |

Четко выраженное согласие или |

|

|

несогласие с предположением |

|

|

клинициста |

|

Побуждающий |

Разнообразная информация, иногда |

|

|

отклоняющаяся от основной темы |

|

Непрямой |

Самоанализ мыслей и чувств |

|

Проективный |

Информация, вскрывающая убеждения |

|

|

и ценности |

Вопросы могут сказаться на спонтанности вербального самовыражения и вызвать защитную реакцию клиента, особенно если интервьюер задает не сколько вопросов подряд. Клиент может стать пассивным и ожидать, пока интервьюер задаст нужный вопрос. Это приводит к парадоксу: интервьюер обычно начинает задавать вопросы, потому что ему нужна информация, од нако слишком многочисленные вопросы снижают вербальную активность клиента и вызывают защитную реакцию, в результате чего клиницист не по лучает достаточной информации. Злоупотребление вопросами может также вызвать зависимость: клиент начинает слишком сильно полагаться на вопро сы и ответы интервьюера относительно важных проблем своей жизни. Опятьтаки, нужно отметить, что более директивные направления психотерапии обычно рекомендуют использовать прямые вопросы и рассматривают тераписта

Прорастают на почве непонимания под воздействием любопытства

на основае существующих или мыслительных фактов

Хорошо поставленный вопрос — тот, на который участник деловой беседы захочет ответить, сможет ответить или над которым ему захочется подумать, и он будет заинтересован в сотрудничестве. Умение ставить вопросы есть необходимый признак ума или проницательности.

Деловая информация далеко не всегда поступает к нам в том объеме, как нам хотелось бы. Во время делового общения часто приходится добывать необходимые сведения у своих партнеров, расспрашивая их обо всех существенных сторонах дела. Спрашивать — значит приобретать сведения и выражать оценку полученной информации.

To ask means to show interest in a partner and a willingness to give him time. However, with its inept, annoying, inappropriate questions, the opposite effect can be achieved: instead of information, the partner will “close”, alert, or even refuse to cooperate. That is why it is so important to be able to properly ask (pose, formulate) questions.

German philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote:

“The ability to raise intelligent questions is already an important and necessary sign of intelligence or insight. If a question in itself is meaningless and requires useless answers, then, apart from shame for the questioner, he sometimes has the disadvantage that leads an imprudent listener to absurd answers and creates a ridiculous sight: one (in the words of the ancients) milks the goat, and the other keeps it sieve.

A well-posed question is one that a participant in a business conversation wants to answer, be able to answer or that he wants to think about, and he will be interested in cooperation.

One way or another formulation of the question (its formulation) can achieve a variety of goals:

It takes courage to ask. After all, asking questions to another means discovering one’s own position, making one’s own value system transparent to another.

It is noticed that it is better to begin a business conversation with a series of questions prepared in advance. By the very fact of the question you show that you want to participate in communication, ensure its further flow and deepening. This convinces the interlocutor that you show interest in him and the desire to establish a positive relationship. To keep the conversation going, it’s also better to ask questions than say monologues. The art of persuasion is to lead the interlocutor to the desired conclusion, and not to impose this conclusion by the power of logic, voice or authority.

The formulation of questions requires not only their thorough preparation, but also the development of their system, thinking over the formulations. This is a key link for information. It is here that the foundation is laid for activating business communication, its creative focus. It should be remembered that for various reasons most people are reluctant to answer direct questions (fear of transmitting incorrect information, insufficient knowledge of the subject, business constraints, restraint, difficulty in presenting, etc.) Therefore, you first need to interest the interlocutor, explain to him that answering your questions is in his interest.

As a rule, the goal of the dialogue, which is always based on the question-answer scheme, is reduced to the analysis of a problem. For a comprehensive, systematic coverage of the situation requires an appropriate set of questions.

There are several types of questions that are commonly used in business communication: at negotiations, meetings, at business meetings.

A closed question is a question that can be answered unambiguously (“yes”, “no”, give an exact date, name or number, etc.) For example: “Do you live in Moscow?” - “No”. “Do you drive a car?” - “Yes.” “Which university did they graduate from and when?” - “MSU, in 2012”.

Closed questions should be accurately formulated, suggest short answers. Usually they either begin with the pronoun “you” or contain it in an interrogative construct. For example, "You claim that ...", "Would you mind if ...", "You will not deny that ..."

In any business conversation, they are inevitable, but their predominance leads to the creation of a tense atmosphere, since it sharply narrows the “room for maneuver” for a partner who may get the impression that he is being interrogated.

Usually they are asked not only to get information, but to get agreement from the partner or confirmation of the previously reached agreement: “Could we not meet tomorrow?” - “Of course”; "Will the cargo arrive on Thursday?" - "No, on Saturday."

An open question is a question that is difficult to answer briefly, it requires some explanation, mental work. Such questions begin with the words “why”, “why”, “how”, “what are your suggestions”, “what will your decision be about”, etc., and this implies a detailed answer in a free form. Open questions are asked in order to obtain additional information or to find out the real motives and position of the interlocutor, they give him the opportunity to maneuver and a more extensive statement.

The main characteristics of this group of questions are as follows:

However, open questions give the opportunity to the interlocutor to get away from a specific answer, to provide only information that is beneficial to him, and even lead the conversation away. Therefore, in the course of a business conversation, it is recommended to ask leading, basic, secondary, and questions of other varieties.

Guiding questions - questions that are formulated in such a way as to prompt the interlocutor for the answer expected from him.

The main questions are open or closed questions that are planned in advance.

Secondary, or subsequent, questions - planned or spontaneous, which are asked to clarify the answers to basic questions.

The alternative question is something in between: it is asked in the form of an open question, but it offers several pre-prepared answers. For example: “How did you decide to become a lawyer: consciously chose this specialty, followed in the footsteps of your parents, decided to do with a friend, or you don’t know why?”; “In your opinion, when is it better for us to hold the next meeting: already this week or will we transfer it to the next?”

In order to talk to the interlocutor, you can try to use alternative questions, but it is important that none of the alternatives touch him. In order to somehow organize a conversation with too talkative interlocutor, it is better to use closed questions.

It is recommended to soften the questions that may offend the interlocutor, and formulate them in the form of an assumption. For example, instead of the question “Are you afraid of not coping?”, The wording is recommended: “Or maybe some circumstances will prevent you from doing this work on time?”

You should not ask a question if you know the answer to it in advance. It is not recommended to start the question with the words: “Why did you not ...?” Or “How could you ...?” The really competent question is a request for information, and not a hidden charge. If you are dissatisfied with the decision of the partner or his actions, try to tactfully but firmly tell him about it in the form of approval, but not in the form of a question.

Rhetorical questions do not require a direct answer and are set with the purpose of provoking a reaction from partners: to focus their attention, to enlist the support of the participants of a business meeting, to point out unresolved problems. For example: “Can we consider what happened as normal?”; “We after all hold a common opinion on this issue?”; “When will people finally understand each other?”

Rhetorical questions are important to formulate so that they sound brief, relevant and understandable to each of those present. The silence received in response to them will mean approval of our point of view. But at the same time one should be very careful not to slip into ordinary demagogy and not get into an uncomfortable or even funny position.

The critical issues keep the conversation within the strictly established framework or raise a whole range of new problems. In addition, they usually allow to identify vulnerabilities in the position of a partner. Here are some examples: “How do you imagine the prospects for the development of your department?”; “What do you think: is it necessary to radically change the management system in large organizations?”.

Similar questions are asked when you want to switch to another problem or when you feel the resistance of a partner. Such issues are dangerous because they can upset the balance between the parties. The interlocutor may not cope with the answer, or, conversely, his answer will be so unexpected and strong that it weakens the position and breaks the plans of the questioner.

Questions for consideration compel the interlocutor to carefully analyze and comment on what has been said. For example: “Did I manage to convince you of the need to revise the terms of the contract, or do you think that we will cope with the situation that has been created?”; “What measures can you take?”; “Did I understand your sentence correctly about ...?”; "Do you think that ...?"

The purpose of these questions is to create an atmosphere of mutual understanding, to sum up the intermediate and final results of a business conversation.

In the course of answering this type of question:

The mirror question consists in the repetition, with interrogative intonation, of a part of the statement uttered by the interlocutor in order to make him see his statement from the other side. This allows (without contradicting the interlocutor and not disproving his statements) to optimize the conversation, to introduce new elements into it, giving the dialogue a genuine meaning and openness. Such a technique gives much better results than the cycle of “why?” Questions, which usually cause defensive reactions, excuses, searches for imaginary reasons, a dull alternation of accusations and self-justification and as a result lead to conflict.

Test questions help manage the attention of the partner, allow you to return to the previous stages of work, and also to check the achieved understanding.

It should be noted that control questions such as “who, what?” Are oriented to facts, and questions “how, why?” Are more focused on a person, his behavior, his inner world.

To the above types of questions should be added the so-called questions-traps , which can ask the opponent initiator of communication. The latter should be able not only to ask questions correctly, but also to answer them, while taking into account the opponent's goals. In the process of communication should be prepared for the following types of questions-traps.

Competency questions. The purpose of such questions is to assess the knowledge and experience of the initiator of communication. As a rule, the author of such a question already knows the answer, but wants to check how the presenter will cope with it. If you have clearly recognized this type of question, you can politely ask: “Why are you asking a question that you yourself know the answer to?”

Questions aimed at demonstrating their knowledge. The purpose of such questions is to show off their own competence and erudition in front of other participants in the conversation. This is one of the forms of self-assertion, an attempt by a “smart” question to earn the respect of a partner If the question really relates to a business meeting, then you can ask the author to answer it yourself. By asking a question, your interlocutor is unlikely to expect such a request. After he finishes his answer, you can add it.

Knocking questions have the goal to transfer the attention of the initiator of communication in the area of interest of the questioner, which lies away from the main direction of work. These questions may be asked intentionally or unintentionally because of the desire to solve some of their own problems. The initiator of communication should not succumb to the temptation and go away from the essence of the issue. It is better to offer to consider such a question at another time.

Provocative questions often try to catch the interlocutor on the contradiction between what he says now and what he said earlier.

If it so happens that you cannot justify such a contradiction, then it is better not to try to justify yourself. By defending yourself, you will convince other participants in the business meeting of the truth of the provocative remark. But even if you are right, and the inconsistency of your words has objective reasons (you can prove it), you still should not use the opportunity to deal with a provocateur.

To get involved in the "dismantling" - not the best way to gain the authority of those present. At best, after your victory, your opponent will fall out of work, at worst, he will look for an opportunity to take revenge later. Demonstrate that you are superior, invulnerable to such “pricks” - and earn the respect of other participants in the business meeting.

Regardless of the type and nature of the questions, one should strictly adhere to the basic principle - to answer the question only if its essence is completely clear.

So, asking questions in the process of business communication, you can get professional information from a partner, get to know and understand him better, make the relationship with him more sincere and trustworthy, as well as find out his position, discover weaknesses, give him the opportunity to sort out his mistakes. In addition, with the help of questions, we maximize our interlocutor and give him the opportunity to assert himself, thereby facilitating the solution of the problem of his business meeting.

If you ask a question, in any context, you take control of the conversation. Questions are inherently directive and are an integral part of human communication. As part of a clinical interview, questions are considered as a separate technique, and therefore deserve special attention. It may be difficult for the interviewer to suppress the desire to ask the client, especially if he needs certain information. Unfortunately, as in the situation described by Sentekzyuperi, there can be no guarantee that the questions asked to the client (and, accordingly, the answers to them) represent at least some interest for him.

Both the client and the interviewer may react painfully to questions. To optimize the use of questions, remember the following principles.

1. Prepare a client for questions.

2. Do not use questions as a primary response to a hearing or action.

3. Your questions should be related to customer problems.

4. Use questions to identify specific, specific examples of customer behavior.

5. Be careful when touching delicate topics.

Prepare the client for questions

A simple technique that reduces the risk of potential side effects is to warn and prepare the client for an intensive survey. Often this helps the client not to be hostile to questions and promotes his cooperation with the interviewer. You can warn the client in this form:

“I need certain information. So for some time I will ask you questions that will help me get it. Some of these questions may seem strange or meaningless to you, but I assure you they are all worthwhile. ”

Do not use questions as a primary response to a hearing or action.

Questions should always be used in conjunction with other hearing responses, especially non-directive. The client's response to the question from time to time must be accompanied by your hearing response.

Interviewer: What happened when you first got on the subway?

Client: When I entered the car, my heart began to pound like a hammer. I thought I was going to die. I clung to the metal handrail next to this day with all my might, because it seemed to me that I would fall down and would laugh at me. At my stop I got off and after that I never used the metro.

Interviewer: So you were very scared. You have done your best to maintain composure. Has anyone been with you during this panic attack?

If the questions do not alternate with adequate emotional responses to the hearing, the client may perceive the interviewer's behavior as agressive or questioning ( Benjamin, 1981 , 1987; Cormier & Nurius, 2003).

Your questions should be related to customer problems.

The client will soon begin to treat you as a competent, trustworthy specialist, if you focus on his most important problems. Therefore, for the effectiveness of your questions, ask directly about what the client himself considers important.

It is sometimes difficult for clients to understand the purpose of certain diagnostic questions or questions aimed at the study of mental status. For example, when interviewing a client suffering from depression, it is necessary to find out what his appetite is, sleep, concentration of attention, sexual activity, etc. The following questions are relevant.

“У вас нормальный аппетит?” “Вы хорошо спите ночью?”

“Вам не трудно концентрировать внимание?” “Вы испытывали в последнее время сексуальное влечение?”

Представьте себе, как страдающая депрессией клиентка, раздражитель ная, не знакомая с психологией, считающая (отчасти справедливо), что ее ненормальное состояние вызвано десятилетним эмоциональным прессин гом со стороны мужа, может отреагировать на подобные вопросы. Она, ве роятно, подумает: “Какой странный консультант! Какое отношение имеют мои аппетит, сон, сексуальная жизнь и внимание к той проблеме, с которой

Не пользуясь книгой, выполните следующие задания.

1.Приведите два примера открытых вопросов.

2.Приведите три примера закрытых вопросов.

3.Приведите пример побуждающего вопроса.

4.Приведите пример непрямого вопроса.

5.Приведите пример проективного вопроса.

Если вы хорошо разбираетесь в разных видах вопросов, которые применя ются в клиническом интервьюировании, выполните следующие задания.

1.Найдите партнера и попрактикуйтесь, задавая разные виды вопросов.

2.Сядьте, расслабьтесь и представьте, как и в каких ситуациях вы мо жете использовать разные типы вопросов. Представьте, что вы спрашиваете клиента во время интервью.

3.Задавайте вопросы разных типов, записывая себя на видеоили аудио кассеты.

япришла?” Если

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 Formulating and using questions to solve problems and manage your life

Часть 2 Пример вопросов для дискуссии к по произедению А.П. Чехова "Человек

Comments

To leave a comment

Interrogation: Questions as Tools for Thinking and Problem Solving

Terms: Interrogation: Questions as Tools for Thinking and Problem Solving