Lecture

Mythologization or secondary designation does not exhaust the possibilities of subjective influence on intraceptive sensations. The fact is that a disease is not just some, even a very unpleasant state, it affects the very foundations of human existence.

The simplest consequence of such a change is the restriction of a person’s freedom, the narrowing of the possibilities of his activity. These are either limitations that do not allow him to do this or that job, reduce movement opportunities, etc., or generally frustrate the basic needs of social and physical existence. The disease not only limits the ability of a person in the present, but also narrows the normal temporal perspective of human life, only in the context of which it makes sense (Tkhostov, 1980; Muladzhanova, 1983; Nikolaeva, 1987).

However, this is not the only possible attitude towards the disease. Paradoxically, the disease can also have a positive color, for example, it can be a way to solve life problems. It hurts a person to pay more attention, he enjoys a special

privileged economic and legal status and other benefits. There is a whole range of types of personal attitudes towards a disease: illness as an “enemy”, “punishment”, “weakness”, “decay”, “relief”, “way of solving life problems”, “loss”, “value”, etc. ( Pfiferling , 1982). The choice of attitude depends on cultural traditions, type of mentality, system of valuable orientations. One should not, of course, think that a person is osno-nano “chooses” what type of relationship to follow. For a sick person, the significance of the disease is formed primarily through the refraction of its subjective picture in the structure of its needs, motives, value orientations, etc. For us, this is important because, like the case with a secondary sign, the choice of the type of relationship is not indifferent to intraceptive sensations. Before proceeding to a systematic presentation of the variants of semantic mediation of bodily intraceptive sensations, it is necessary to consider the general principles for solving similar problems in other areas of psychology and discuss some important theoretical issues.

The effect of motivation on perceptual activity has been a well-known phenomenon for a long time. The idea of such influence became the cornerstone of psychoanalysis, which believed that motivation, as directly reflected in the so-called primary processes (imagination, dreams, dreams), obeying the "pleasure principle", and breaks through in the secondary (thinking, perception, memory) in the form of specific reservations, mistakes, forgetting (Freud, 1924). If in the primary processes nothing interferes with the realization of libidinal drives “Id”, then the socio-cultural limitations of the “Super-Ego” make it difficult to implement them in the secondary ones. This energetic contradiction leads to a neurotic symptom - as the result of a “breakthrough” of unresolved motivational stress. The symptom is the substitution manifestation of unrealized attraction, the result of the psychological defense of “Ego” in the face of reality, which makes it impossible to satisfy the drives of “Id”. Psychoanalysis has developed a rather harmonious classification of types of defenses, some of which, such as, for example, “suppression” and “regression”, convert psychological stress to a somatic organ ( Sjoback , 1973; Laplanch , Pontalis , 1963; Laplanch, Pontalis, 1996; Bellak , 1978; Bergeret , 2000).

Psychoanalysis has managed to catch the fact that bodily phenomena can go far beyond the bounds of their content, gaining life.

in new ways. True, it should immediately be stipulated that the main efforts of researchers in this direction concentrated on answering the question “why” the conflict acquired a bodily expression, and not “how” he does it (Arina, 1991). The answer to the question "why" is devoted to the numerous works of 3. Freud himself and his followers - representatives of classical psychosomatics. In the most general form, they boil down to the fact that “conversion to an organ” symbolically resolves an affectively charged situation. The occurrence of many diseases can be understood on the basis of the tendency of repressed desire, manifested through a disorder of the body, and there is a clear connection between the content of the conflict and the clinical symptoms. “The choice of body” is determined by its symbolic meaning and connection with the content of the conflict ( Juliffe , 1939; Bassin, 1968, 1970). “Psychological symptom - conversion by means of organs of the body, in the language of the body in the form of allegory, embodies the conflicting meaning” (Arina, 1991, p. 47).

It is much more difficult to find the answer to the question “how” this happens in the works of psychoanalysts. For Freud himself, this problem did not exist. In this, he was quite firmly in the position of the physiologism of the end of the 19th century, who was looking for a corresponding physiological process behind every physical manifestation. Although no direct statement can be found anywhere in his works, it can nevertheless be assumed that in those cases when it was not a question of a real illness resulting from the conflict, but symbolic complaints, the source of bodily sensations was not any libidinal energy, understood in the style of P. Janet or A. Bergson.

The mechanism of influence of this energy was understood in “hydraulic” terms. “The process of incarnation in the symptom Freud described with the image of a river flowing along two channels: an obstacle in the path of movement of the flow of unconscious meanings and experiences in the first channel necessarily leads to overflow in the channel connected with it — this is the breakthrough of the unconscious. For Frey, it does not matter whether there was a breakthrough in the sphere of bodily functions (and then a psychosomatic symptom such as conversion arises) or in the sphere of open behavior (and then many symptoms of "psychopathology of everyday life" occur). There is no definite answer to the question about the carrier of meaning in the bodily channel ” (ibid., P. 46).

To this we can add that the most modern psychoanalytic studies ( Bergeret , 2000) in the interpretation of psychosomatic relations do not differ too much from the conditioned reflex schemes and the theory of operant conditioning. Difficulties

explanations of conversion at the symbolic level were partially solved using physiological mechanisms. If the emotions accompanying the conflict cannot be adequately expressed, they turn into chronic vegetative changes and, subsequently, into organic disorders ( Dunbar , 1943; Alexander , 1952; Makhin, 1981; Holland , Rowland , 1989). As you can see, although the problem of semantic regulation of corporeality was the core of the theory itself, it was understood only in the context of the pathogenesis of the disease, body sensations themselves, in full accordance with the traditions of objectism, clearly corresponded to physiological events in the body.

In a somewhat different way, the problem of the influence of human needs and motives on bodily sensations and diseases has been developed in recent years within the framework of the “hermeneutic direction of health research” in the United States (Tishchenko, 1987a). The main ideas of this approach are based on the philosophical views of X. Gadamera ( Gadamer , 1976; Gadamer, 1988).

The idea of the hermeneutic approach is based on an attempt to bring to human science the achievements of humanitarian knowledge, to change the understanding of a symptom. Although numerous studies have demonstrated the effect of cultural design on the manifestation of a natural symptom, most doctors have a negative attitude to this idea. The reason, as we have already noted, is that for a doctor a symptom is only a manifestation of biological reality and the influence of culture can only distort it.

The hermeneutic approach asserts the fundamental impossibility of the coincidence of the order of words (reflecting realities) and the order of things (reflected realities), and this discrepancy reveals a special meaning. It is not enough to simply "... establish a relationship" a sign (symptom) - an object (breakdown of the body). " It is fundamentally important to find that “paths” - a turn that occurs in a natural language and turns object-oriented knowledge into personality-oriented. Therefore, each state of the body is normal and the pathology is experienced by a person as a fundamental semantic (hermeneutic) phenomenon, which requires “interpretation” for its understanding. Although each of the diseases has some biological or physiological correlates (causes), however, these causes become facts of human experience or suffering only through perception, interpreted

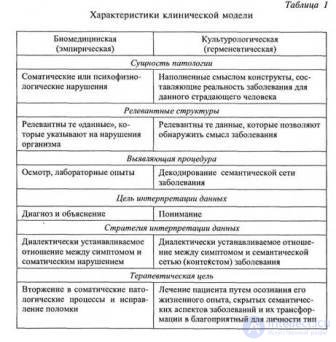

expression, and addressing the "other", i.e. entering the world of human words and humanitarian discourse. In this situation, the symptom acquires personal meaning — it becomes a request addressed to another person, and the set of symptoms (syn drom) turns into a text that requires reading. For example, a symptom of anorexia (refusal to eat) can serve as a metaphor for the inadequacy of mother-child interpersonal communication ” {Tishchenko, 1987a, p. 107). The hermeneutic procedure allows you to move from the healing of the disease to the healing of the patient, to reorient the copper tsin from the “object” to the “personality”. The radicalism of the reorientation of medical knowledge is shown in Table 1 ( Good , Good , 1976).

In some aspects, the hermeneutic approach is close to psychoanalysis, especially its semiological modifications ( Lacan , 1949). The undoubted merit of this direction is the orientation of medicine to humanitarian knowledge, but the task of consistently working out the entire path from the primary body sensation to the meaning in it is not only not fulfilled, but not even posed at least to the extent, as was done in psychoanalysis.

Moreover, the biggest disadvantage of the hermeneutic approach is that with its humanitarian constructs it simply complements natural science medicine, dualistically doubling the world: “... on the one hand, the physical world, and on the other, the world of language. It is assumed that natural science knowledge can exist outside the context of humanitarian discursiveness, and humanitarian knowledge can exist naturally outside scientific dis cusivity. Therefore, supporters of the hermeneutic approach only "complement" the paradigm of the biological model of medicine, which is understood from the standpoint of physicalism, and categorically refuse to rethink it ... If this doubling is left, then it is extremely difficult to refute the following objection. There is no doubt that there is “medical folklore”, that there are personality traits of perception of suffering, that the totality of symptoms can be read as a text expressing a certain personal meaning. However, if the doctor finds a good medicine that can restore the damage to the body, then the person will not be able to express their personal meanings in the language of suffering (there is no provoking factor, there is no language). Thus, the biological approach has a much higher priority than the hermeneutic one ” (Tishchenko, 1987a, p. 108).

In addition to the question of priority, such a dualism, splitting a person into a Cartesian automaton that obeys physical laws, and a linguistic subject belonging to a different reality, makes it difficult to specifically decide how semantic formations can affect purely physical ones.

The problem of the mechanisms of the influence of needs on perception has been most consistently and convincingly developed in the psychology of extraceptual perception, especially in the works of the New Look school. Starting with the works of M. Sheriff, a huge amount of research was conducted that convincingly proved motivational

the conditionality of the distortions of assessing the size, shape of objects and changing perception thresholds depending on the interests and needs of the subject ( Ansbacher , 1937; Levine , Chein , Murphy , 1948; Rosen , 1954; Wispe , Dramberean , 1953; Bruner, 1977). The possibilities of a motivational influence on perception were quite convincingly written into the scheme of a perceptual act. The perceptual act was built in several stages.

Primary categorization. From the very beginning, within the framework of this scheme, it is necessary that the phenomenon be perceptually isolated from the environment and that certain spatial and qualitative characteristics be attributed to this phenomenon. At this stage, it is sufficient to attribute, for example, values such as “object”, “sound” or movement (in our case “pain”, “movement”, “change in rhythm”, “discomfort”, etc.).

Search for signs. In the context of a familiar activity or a highly probable connection between a trait and category, hidden and unconscious, there can be a second stage: a more precise identification with the help of additional traits. In the case when compliance with available categories is incomplete or communication is unlikely, a special (possibly conscious) search for signs is necessary. Under these conditions, the channel for stimulation is open maximally.

Confirmatory check. After a search for signs confirming assignment to a certain category, the nature of the process changes dramatically. The degree of openness towards irritants is narrowed down: only additional signs are sought in order to control and confirm trial identification. This is a process of selective adjustment, which results in a decrease in the effective level of stimulation, which is not related to the process of confirming the achieved categorization.

Final confirmation. If the identification is successful, the search for attributes is completed. This stage is characterized by a sharp decrease in sensitivity to extraneous stimuli: incompatible signs are normalized or eliminated. As soon as an object belongs to a certain category characterized by high probability and good agreement, the threshold for distinguishing features that contradict this categorization rises almost by an order of magnitude.

From the very beginning, with the initial categorization and search for signs, the categories used may have a varying degree of subjective acceptability. To explain the effect of motivation on perception, three mechanisms were used to ensure its selectivity:

• The principle of resonance - incentives that are relevant to the needs, values of the individual, are perceived more correctly and faster than they do not correspond to them.

• The principle of protection - incentives that contradict the expectations of the object or carry information that is potentially hostile to the “Ego”, are less well known and are subject to greater distortion.

• The principle of sensitization - incentives that threaten the integrity of the individual, are recognizable most quickly (Bruner, 1977; Vgi ner , Postman , 1949; Bruner , Postman , John , 1949; Postman , Bruner , Walk , 1951).

Researchers of the New Look school have worked out well and have described the phenomena of perceptual protection, sensitization and other motivational distortions of extracepticism very carefully. There is every reason to believe that, to an even greater degree, this influence should manifest itself in intraception, which, on the one hand, has great potential for distortion, and, on the other, the high motivational significance of the disease.

The great achievements of the school “New look” in explaining the perceptual mechanisms of distortion itself do not allow, however, to unequivocally answer the question about the form of their (mechanisms) connection with needs. Although common sense, personal experience and scientific evidence convince us that our needs can significantly affect the perception and subjective experience of the upcoming reality, this does not save us from having to explain exactly how this happens, otherwise the needs become a homunculus that is in our self and sorting sensory data.

The most serious methodological difficulty is that in order to solve this problem it is necessary to find a way to transfer the internal state of the need into the sphere of a perceptual act. This is not as simple as it seems at first glance, since it is necessary to reconcile needs as an energy reality with its regulation of subtle and specific processes of reflection.

The problem of motivation, despite its apparent simplicity, is one of the most methodologically complex psychological problems {Rubinstein, 1957, 1999; Leontyev A.N., 1966, 1975, 1981; Vilyunas, 1976, 1983, 1990; Sokolova, 1976, 1980; Sokolov, Nikolaev, 1995; Guldan, 1982, 1984; Stolin, 1983). Motivation, unlike the stimulus that is already given in the

act requires a search for missing or not yet existing situations or objects 1.

Usually, although not always consciously, motivation is understood as a “negative state” —a physiological need, the ability to respond to stimuli in a specific way, derived from the properties of a living organism. In other words, motivation is a state of the organism, whose function is to lower the reactivity threshold. In this case, the motive is “energizer” or “stabilizer tor.” For a variety of reaction forms, the concepts of learning or a conditioned reflex are used. Obviously, in both cases, the concept of “motivation” is in fact excessive, stimulation and learning are sufficient to explain behavior (Newtten, 1975).

Such a scheme is very difficult to include in the perceptual act, since neither its regulation on the basis of reflection, nor the reverse process of influence on experience and reflection, can be deduced from the energy understanding of the need. The difficulties of adequately addressing this task have given rise to several attempts to distinguish in the motivation, apart from the energy component, special derivatives “meaningful variables” (valences, in contrast to the needs of K. Levin, “needs” and “presses” for G. Murray, “drives” and “ incentives among behaviourists), but none of them can be considered sufficiently consistent.

The most successful way out of this situation is proposed in the theory of motivation by A.N. Leontyev (1981) and its subsequent development by V.K. Vilyunas (1983). The main idea, which allowed to solve the described difficulty, was the principle of objectivity of necessity. Вместо категории потребности в этом подходе исполь зуется категория мотива, или опредмеченной потребности, позво ляющего перевести диффузное состояние неудовлетворенности, нужды — в целесообразную «ориентированную» деятельность. «...Потребность, объективировавшая себя в отражаемом мире и как бы передавшая функцию организации деятельности предмету, способ ному ее удовлетворить, является реальной основой процессов мо тивации. Актом опредмечивания потребность семантизируется, впи тывает в себя определенное содержание, и впредь она проявляется уже в этом содержательном оформлении... Будучи "слепой", она приводит лишь к нецелесообразной активности, обнаруживая при

-1 J. Nütten gives a clear example: “In laboratory conditions, the experimenter considers food as a stimulus acting on the taste organ of an animal and studies the physiological secretion it causes, but for someone who observes the behavior of an animal in natural conditions, food is an object- the goal of a long- term motivated activity ” (Newtten, 1975, p. 19).

this, however, is a strong tendency to “see the light”, to concretize in something definite, material ” (Vilyunas, 1983, p. 192-193).

The product of this process — the motive — becomes a double formation: on the one hand, the subject, on the other, the need, or even more precisely, the need “manifest” through the subject. The subject becomes a motive, engaging in a semiotic relationship with need, meaning it. Understanding the motive as a semiotic subject allows us to solve two problems simultaneously: the necessity of the object and the functions of meaning formation. “This means that the blind energy of need does not manifest itself as a psychic as an independently acting force, that it is enriched by acquired experience, which is introduced into the demand mechanism by a special process (objectification), formed in it and becomes an integral component of it. Only such objectified energy or, otherwise, the energy-induced object comes into interaction with the processes of reflection ... "(Ibid., P. 193).

The semiotic nature of the motive makes it possible to consistently explain the possible influence of need on cognition, which generates its bias, since it (the motive) is an education of the same order as other images, representations or meanings. The fact that item 2 becomes a motive turns it into an “exciting” item. “Partiality is the language by which needs indicate their subjects to the surviving subject; Representing the need for the image of an object, bias constitutes in it an advantage over other images, which is manifested in its ability to cause orienting processes and activities ” (Ibid., p. 196).

В конкретной ситуации предметность реализуется в смыслообразующей функции мотива, порождении им личностного смыс ла. В концепции деятельности мотивационный процесс с актуа лизацией мотива не завершается, а разворачивается в новую фазу, в которой предметы и условия, связанные с мотивом, тоже полу чают особую смысловую окраску. В смысле, как специфической единице психического, субъекту открываются не объективные свойства отражаемых объектов и ситуаций, а та особая значимость, которую они приобретают своей связью с актуальными мотивами, что особенно очевидно проявляется в случаях несовпадения такого смыслового и общепризнанного стандартного значения (см.: Вилю-

-2 Предмет не следует понимать субстанционально. У А.Н. Леонтьева сло во «предмет» используется в философском смысле и «безразлично при этом, идет ли речь о материальных объектах... или отвлеченных, выступающих в форме идеи, некоторой ценности, некоторого идеала и т.п.» (Леонтьев А.Н., 1966, с. 5).

нас, 1983, с. 198). Это, на наш взгляд, наименее разработанное и наиболее противоречивое место концепции А.Н. Леонтьева. Самым неясным остается то, как конкретно реализуется смысл, в чем он «содержится». С одной стороны, А.Н.Леонтьев сам подчеркивал, что «смысл — это всегда смысл чего-то. Не существует "чистого" смысла. Поэтому субъективно смысл как бы принадлежит самому переживаемому содержанию, кажется входящим в значение» (Леон тьев А.Н., 1975, с. 278). С другой стороны, он же отмечал, что «хотя смысл и значение кажутся слитыми в сознании, они все же имеют разную основу, разное происхождение и изменяются по разным законам. Они внутренне связаны друг с другом, но только отноше нием, обратным вышеуказанному: скорее, смысл конкретизирует ся в значениях (как мотив — в целях), а не значения — в смысле. Смысл отнюдь не содержится потенциально в значении и не может возникнуть в сознании из значения. Смысл порождается не значе нием, а жизнью» (Там же, с. 279). Это все вполне справедливо, но остается совершенно загадочным «местопребывание» смысла. Леон тьев неоднократно подчеркивал, что хотя смысл и может быть «выражен» в значениях, но может существовать в форме переживания, эмоции или интереса.

Как замечает В.К. Вилюнас, «определение, утверждающее, что эмоции регулируют деятельность, "отражая тот смысл, который имеют объекты и ситуации, воздействующие на субъекта" (Леон тьев А.Н., 1971, с. 28), можно понять так, что эмоции сами вы ражают смысл, являются формой его существования, но оно по зволяет также думать, что смысл имеет независимое онтологическое выражение (в чем? — А. Т.), тогда как эмоции его отражают, о нем сигнализируют» (Вилюнас, 1983, с. 199). Сам А.Н.Леонтьев, на сколько можно судить, склонялся к последней трактовке, утвер ждая, что эмоции способны ставить субъекту «задачу на смысл», из чего следует, что эмоция — еще не смысл, что смысл возникает вслед за эмоцией, в результате решения субъектом поставленной ею задачи.

Между тем, можно утверждать, что между смысловыми и эмоциональными явлениями нельзя провести четко очерченной грани, что эмоциональные отношения есть основа смысловых образований, а понятие смысла служит лишь для специфической кон цептуальной интерпретации этих отношений (Там же).

Более того, признать существование смысла не в категориях значений столь же затруднительно, как представить данную сознанию некатегоризованную чувственную ткань. Совершенно другое дело, что уровень категоризации неоднозначен, что могут существовать различные способы его презентации. Признание же «первовидения» в виде эмоциональной категоризации вообще снимает проблему,

давая смыслу область, необходимую для его реализации и не огра ниченную сферой вербальных значений, а проблему диссоциации значения и смысла трансформирует в проблему несовпадения эмо циональных и вербальных значений (или разных уровней категори зации). На уровне же самого «первовидения» проблема диссоциации вообще снимается, так как эмоциональное значение не может «зна чить» ничего иного, кроме себя самого, и иному смыслу будет со ответствовать и иное значение.

Indeed, meaning is expressed in meanings, and only in them can it exist, but one should understand the meaning broader than A.N. Leontyev, who reduced it mainly to the ideal form of crystallization of social experience, fixed in “a sensual carrier of it, usually in a word or word combination " (Leontiev, AN, 1975, p. 275). Expanding the understanding of the value removes the terminological debate on the qualification of meaning: A.R. For Luria, meaning is an individual meaning, in Van der Velde it is conditionally related to the signal content, in Titchener it has a complex contextual meaning, in Bartlett it is a value created by the integrity of the situation (see: Leontyev A.N., 1975). In my opinion, this is an empty argument. Meaning may be each of these phenomena, it does not have a permanent residence. Really being born not from value, but from life, it becomes accessible to consciousness only through a system of values. Repeating, we can say that the meaning expresses itself through values, by choosing or rejecting, limiting or, on the contrary, expanding the semantic field, its design. Meaning is substantiated in meaning as a kind of “meaning of meaning”, cutting, expanding or otherwise transforming the categorical network. Through the function of meaning, supralitonal, culturally developed universals acquire their individual existence, which can differ significantly from the generally accepted one. The value is always meaningful; in the event that it has nothing to do with needs, it has the meaning of a neutral, outside the sphere of interests, “known”. A.N. Leont'ev himself comes close to this understanding, however, on the other hand, from the side of meaning: “... When functioning in the system of the individual consciousness, values do not realize themselves, but the movement of the personal sense that embodies them. -being a particular subject. Psychologically, i.e. in the system of consciousness of the subject, and not as its subject or product, meanings do not exist at all except as realizing certain meanings ” (Tam oka, p. 153).

Substantially the meaning is a phantom and, devoid of its own flesh, meaning, it disappears, as the form that is not filled disappears

no content. Through personal meaning, structured objectification (transformation into a motive) amorphous needs manifest themselves with the bias of human consciousness.

“The difficulties (of the previous psychology. - AT) consisted in a psychological explanation of the bias of consciousness. The phenomena of consciousness seemed to have a double determination - external and internal. Accordingly, they were interpreted as supposedly belonging to two different spheres of the psyche: the sphere of cognitive processes and the sphere of needs, efficiency. The problem of the correlation of these spheres — whether it was solved in the spirit of rationalistic concepts or in the spirit of the psychology of deep-seated experiences — was interpreted invariably from an anthropological point of view, from the point of view of the interaction of factors of different nature.

However, the actual nature of the duality of the phenomena of individual consciousness lies not in their subordination to these independent factors. <...> The fact is that for the subject himself, the realization and achievement of specific goals by him, mastering the means and operations of action is a way of asserting his life, satisfying and developing his material and spiritual needs, objectified and transformed in the motives of his activity. It makes no difference whether the subject realizes motives, signals them about themselves in the form of experiences of interest, desire, or passion; their function, taken from the side of consciousness, is that they, as it were, “appreciate” the vital significance for the subject of objective circumstances and his actions in these circumstances, give them a personal meaning that does not directly coincide with their objective meaning. Under certain conditions, the discrepancy between the meanings and meanings in the individual consciousness can acquire the character of true alienness between them, even their oppositeness ” {Leontyev, AN, 1975, p. 149-150).

This passage contains two important considerations.

The first concerns the fact that the bias of human consciousness exists, and it manifests itself in the form of a mismatch between meaning and meaning, or, more precisely, a discrepancy between objective (general) and subjective (individual) values, or non-coincidence of the “emotional” and “cognitive” sides of meaning. This discrepancy can manifest itself in equal forms: for example, the formation of special methods of categorization, distortion of perception, inconsistencies of the “known” and “experienced” (in cases of reconciliation races at different levels).

The second consideration indicates the source of partiality: the manifestation of motivation through the placement of meaning in the context of vital needs.

Although most often A.N. Leontyev speaks about the meaning of action (as a relation of motive to a goal), meaning is endowed, to the extent that they are related to the subject of activity — motivation, circumstances of action, goals, objects, and indeed any phenomena.

One and the same phenomenon, depending on its position in the motivational structure, can be completely differently evaluated. “Four possible relations can be considered, in which one or another phenomenon can act: 1) the phenomenon acts as a motive; 2) the phenomenon is a condition that prevents the achievement of motive; 3) the phenomenon is a condition conducive to the achievement of motive; 4) the phenomenon is a condition that promotes the achievement of one motive and prevents the achievement of another. Four possible meanings of the phenomenon correspond to these four relationships: the meaning of the motive, the negative meaning, the positive sense, the conflict meaning ” (Calvino, 1981, p. 4).

The complexity of the situation lies in the fact that the requirements themselves are not equal, but hierarchically organized. Therefore, the formation of meaning is carried out not only in the actual situation of actualized need, but is determined by a wider range of stable motivational structures: value orientations, semantic formations, dynamic sense systems and other aspects of personal regulation (Abulkhanova-Slavskaya, 1977; Asmolov et al., 1979 ; Asmolov, 1984; Guldan, 1982, 1984; Vasilyuk, 1984; Bratus, 1988).

Understanding human behavior and the meanings generated in its activities can only be based on the fact that “... for what an action is performed, human activity, or what is the true meaning behind the goals, objectives, motives taken by themselves or in combination . <...> It is the general semantic formations (in case of their realization - personal values), which, in our opinion, are the main constitutive (forming) units of consciousness of the personality, determine the main and relatively permanent relations of a person to the main areas of life - to the world, to other people, to oneself ” (Bratus, 1988, p. 87, 91).

It took us quite a long digression to clarify how the bodily, intraceptive sensation makes sense. Its function of signaling a certain bodily state can be modified, including through various

ways of mythologization into motives and semantic formations not directly related to it. Consider this in more detail. In the most general form, the personal meaning of the disease is the vital significance for the subject of the circumstances of the illness in relation to the motives of his activity. Therefore, the diversity of types of attitudes towards the disease is determined by the diversity of its personal meanings.

The very first level of semantic mediation is manifested in the fact that intraceptive sensations and bodily functions can become a means of expressing not their own natural needs, but others that are not directly related to them, for example, communicative 3. Already the first human need for food, apart from its direct meaning - preserving life, can fulfill the communicative function of communicating with the mother: caprice, renunciation of food as a way of expressing attitudes toward the mother has a different meaning than refusing to eat as a result of satiation.

Nausea as a sign of "relationship" has nothing to do with consignment. Feelings of hunger during a religious fast are not equal to feelings of hunger due to the lack of food or refusal of it in an effort to lose weight. Intraceptive sensations can be given their original meaning after their secondary meaning or mythology. Part of the meaning is given by the selected myth itself. If intraceptive sensations have a special “non-painful” meaning, they are experienced completely differently. Shamanic diseases are not diseases in the generally accepted sense, but a sign of special note, a gift; For many centuries, the holy fools were not sick, but the people of God by their lips, spoken by higher powers, and lepers carried the seal of sin and curses on their bodies ( Foucault , 1961 a, 1963; Ivanov, 1975; Basidov, 1975; Yakubik, 1982) . We have already noted the high variability of pain tolerance in religious groups (Melzac, 1981). An erection is not just a technical condition for sexual intercourse, but a symbol of masculinity, power, perfection, domination, etc.

However, we narrow our discussion to intraceptive, bodily sensations, meaning illness. Let us ask ourselves: how do we

-3 We do not have the opportunity to dwell here on the very interesting problem of the ontogenesis of the communicative function of corporeality, which requires special development. The possibility of its generation is connected with one fundamental moment: the first human needs are inseparable from the cultural way of satisfying them, and the mother is able to give meaning (and objectify, make “opaque”) “natural manifestations”: cry, cry, food as a reward or punishment, etc. ., becoming a means of transmitting a message to another and influencing another, they acquire a new meaning and meaning (Tishchenko, 19876; Koloskova, 1989).

In this case, is it possible to change the meaning of sensations, if they are always interpreted through the general concept of the disease? In our opinion, this is due to the fact that the very meaning of the disease is not uniquely included in the motivational system and can be filled with different meanings. Consider the possible ways of comparing the disease and motivation.

The first position - the disease as a motive - is rather difficult to imagine. If such cases exist, they require some special analysis 4.

The following are much more common: a disease as a condition that prevents achievement of a motive, a disease as a condition contributing to it, and a disease as a condition contributing to the achievement of some motives and an obstacle to the achievement of others.

In the most common case, the disease brings a person suffering, narrows the freedom of human existence, not only in the present, but also in the future. The disease changes the attitude towards the patient by the society. These moments are of particular relevance in cases of severe, deadly disease.

In conducted by us together with N.G. A study of attitudes towards cancer patients on the material of 1000 respondents from various social groups showed the existence of a reserved or negative attitude of society towards cancer patients. Among the population there are widespread ideas about the infectiousness of cancer patients, which cause a large hygienic and household distance. Even if these ideas are not so pronounced, for example, among professional doctors, the distance remains for purely existential reasons: unwillingness to enter into close relations, friendship with doomed patients, requiring moral participation and co-operation. Especially these fears are manifested in the negative attitude of the interviewed respondents towards the establishment of suspected seizures with oncological patients (or rather, with people who were once treated for malignant neoplasms)

-4 Although it is possible to imagine incidents of prayers for a disease as the atonement of sin or a means of attaining bliss, if the disease is regarded as such. Another possible option is something in the style of “Thanatos” in the later works of 3. Freud.

meynyh relations (Gerasimenko, Tkhostov, Koschug, 1986, 1988). Correlated results were obtained on other social samples. In Canada, the attitude of employers in production to patients cured of neoplasms was investigated. Compared to the control group, discrimination against treated patients is 30%, and in the group with an unfavorable course - 100% more. In the United States, 25% of cured cancer patients experience discrimination at work ( Ebermann - Feldman , Spitzer et al., 1987).

Even more obvious is the threat posed by serious diseases to the human physical existence itself. According to our data, about 30% of the population considers oncological diseases incurable.

From what has been said it is clear that malignant neoplasms should frustrate the basic needs of physical and social existence and have a destructive meaning of human self-realization. This obstacle sense must apparently distort the perception of the disease at all levels: from the way of its mythologization (replacing the concept of the disease with a safer one) and meaning to sensual fabric.

Such phenomena, indeed, were repeatedly noted by physicians, which made it possible even to speak about the prevalence of anosognosis in cancer patients (Romasenko, Skvortsov, 1961).

Patients are constantly trying to find a basis that would allow them to avoid the diagnosis of "cancer." Despite the fact that they are all in an oncological hospital and understand well what their neighbors in the ward are ill with, almost everyone is inclined to hope for a “feature” of his own case, that an error occurred to him, that they got here acquaintance ”,“ good doctors are here ”,“ you need to understand ”, etc. Although the reality rather rigidly forces these patients to reckon with themselves, there are many tragic manifestations of the unacceptability of the fatal meaning of cancer: quite frequent refusals of treatment (according to different nymi, from 20 to 30 %), frequent cases of neglected, when patients do not go to the doctor for a long time, despite the obvious manifestations of the disease.

Sometimes it is possible to note the striking "invisibility" of objective manifestations of the disease, ignoring the tumor itself, its size, and underlining the "node reduction". The perception of the incoming information is very selective: what confirms the diagnosis, is quickly forgotten, is considered “unimportant”, the same that allows it to be doubted, is cultivated. This tactic does not depend on the level of education: I watched a radiologist,

who had on her own X-rays of a lung tumor all the signs of the inflammatory process.

To study the characteristics of awareness of their disease with cancer patients, 106 cancer patients were examined and a control group of healthy subjects (50 people) corresponding to them by age, sex and education.

Virtually all patients were fairly well informed or guessed about the nature of their illness. The volume of specific knowledge, their accuracy, compliance with the objective picture of the disease depended mainly on the level and nature of education, medical training and individual experience gained as a result of either their own illness or communication with other patients and their care. In the behavior and statements of patients, there was always a reluctance to recognize the status quo, the desire to simplify the situation. Patients often said that they were well aware that they had cancer, that they did not have long to live, they demanded that they tell them the results of the tests, say “the truth”. Parallel to this, they made little realistic plans, doubted the objectivity of the surveys being conducted, and looked for opportunities for additional consultations. At the same time, the behavior of patients who said that they were convinced of the good quality of their disease also did not always correspond to their statements. They were tense, anxious, and suspicious of each new examination. In assessing their condition, patients constantly ranged from despair to hope. However, the deepest despair did not deprive them of hope for a happy outcome of the disease. Hypochondria, fixedness in their condition combined with a tendency to explain the obvious and for them pathological symptoms for non-oncological reasons. Information was sifted through, hypertrophied exaggeration of temporary improvements and underestimation of the obvious deterioration; Despite the fact that the patients actually saw the course of the oncological disease in the measure of their neighbors, in each there was hope for the “special” character of his case. It is also specific that such anosognosity did not completely relieve anxiety and depressive experiences. Reality never disappeared, but as it were faded into the background, it was specially processed.

To study the assessment of patients with their condition, a modified Dembo-Rubinstein self-assessment method was used ( Rubinstein, 1970). В нашем варианте больному предъявлялись четыре 10-сантиметровые линии, на которых предлагалось отметить свое место между людьми с «самым хорошим характером в мире и

самым плохим», «самыми счастливыми и самыми несчастными», «самыми умными и самыми глупыми», «самыми здоровыми и са мыми больными». Затем больному предъявлялся аналогичный чис тый бланк, и его просили сделать отметки так, как бы он это сде лал до болезни. После этого больного просили объяснить, чем он руководствовался в своих оценках. В отличие от классического вари анта, анализировались не только ответы, но и оценки на шкалах.

Больные отмечали свое положение на шкале здоровья между «самыми здоровыми и самыми больными» близко к середине. Одна ко ретроспективное завышение оценки здоровья говорило о сохран ности хотя бы фрагментарного сознания тяжести своего заболева ния. Осознание ситуации выступало в превращенной форме, как осознание измененности своего состояния, причем диапазон изме нений был сдвинут вверх, к более высоким оценкам. Фрагментарно и содержание, вкладываемое больными в понятие здоровья; на воп рос о том, как объяснить такую высокую оценку своего здоровья, больные обычно отвечали: «Но ведь я сам хожу, сам себя обслужи ваю и по сравнению с другими хорошо себя чувствую». Поскольку почти всегда можно найти больных, состояние которых действи тельно хуже, подобного рода рассуждения позволяли длительное время «уходить» от реальности. Основным механизмом, обеспечи вавшим такую переоценку, являлось не нарушение собственно осоз нания, а искажение его структуры, сдвиг «субъективного нуля», изменение содержания эталона здоровья, позволявшее переоценить, переосмыслить угрожающее положение.

Вместе с этим можно было отметить искажение оценки объек тивной симптоматики в виде «просеивания» информации, повыше ния ее неопределенности. Как уже отмечалось, несмотря на то, что в высказываниях больных частым было требование «всей правды», существенно менялось их отношение к поступающим тем или иным способом объективным данным: позитивные расценивались как яс ные, точные, а негативные — как неопределенные. Специфическая особенность такой «анозогностичности» в том, что она не снимает тревоги и депрессивных переживаний.

Чтобы лучше проанализировать ситуацию искажения смысла, мы провели еще один специальный эксперимент.

Для эксперимента было отобрано 8 изображений Тематическо го Апперцепционного Теста. Отбор осуществлялся таким образом, чтобы изображения были равномерно представлены по следующим категориям:

Испытуемым предлагалось составить по предложенному изображению развернутый рассказ: описать, что изображено на рисунке, какие события привели к данной ситуации, каков ее предпола гаемый исход. Рассказы оценивались с помощью ранговых критериев по степени структурированности, разработанности, конкрет ности, реальности и общего фона рассказа.

Все 8 рисунков оценивались этими же испытуемыми с помощью модифицированной методики Семантического Дифференциала Ч. Осгуда для получения их факторных оценок ( Osgood et al ., 1957; Тхостов, 1980; Петренко, 1983; Шмелев, 1983).

Это исследование было в свое время проведено с иными целя ми, но полученные в нем результаты, не нашедшие в то время адек ватной интерпретации, могут способствовать прояснению нашей ситуации ( Тхостов, 1980, 1984).

Наиболее интересный результат заключался в нарушении струк- турации, осмысления тревожных, негативно оценивавшихся по шкалам Осгуда изображений. Рассказы больных отличались значи тельно меньшей конкретностью и определенностью. Часто вообще не указывался смысл происходящего и вместо развернутого сюжета больные говорили: «что-то делают», «что-то неприятное», «какие- то люди» и пр. Давалось несколько возможных вариантов происхо дящего, без необходимой конкретизации. Рассказы были неполны, ограничены описанием происходящего в настоящем времени, свя заны с описанием неприятных событий. Характер воздействия, как правило, не указывался, оно рассматривалось как «рок», «фатум», тогда как причиной событий в рассказах испытуемых контрольной группы были конкретные лица либо стечение обстоятельств. Наибо лее неопределенными и обобщенными были рассказы по изобрете ниям, оценивавшимся как наиболее неприятные и тревожные.

Особенно важным в этом эксперименте для нас является то, что специфической особенностью таких рассказов было сочетание негативной оценки с высокой неопределенностью, сходной с неоп ределенностью восприятия заболевания. По моему мнению, нару шение структурации негативных стимулов есть своеобразный меха низм перцептивной защиты. Последняя в качестве нарушения восприятия неоднократно описывалась в литературе. В данном

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 Chapter 6. SANIMENTAL MEDICATION OF THE BODY

Часть 2 6.8. Позитивный смысл болезни - Chapter 6. SANIMENTAL MEDICATION OF

Comments

To leave a comment

The psychology of corporeality

Terms: The psychology of corporeality