Lecture

The concept of life and activity in the concept of A. N. Leontiev

Building a typology of "life worlds"

The overall goal of our work is the development of theoretical ideas about experience. From the point of view of this goal, the meaning of the previous chapter was to prepare the conditions for its achievement: we introduced the concept of experience into the categorical apparatus of the theory of activity, identified the corresponding slice of psychological reality and showed how this reality is reflected in already existing concepts. As a result, we have, on the one hand, a very abstract activity-theoretic idea of experience, on the other hand, some idea of the relevant empirical field, given in the form of a set of facts, generalizations, distinctions, classifications and assumptions about the patterns of the experience process. Now the task is to try to expand the initial abstractions of the theory of activity in the direction of this empiricism, i.e. to carry out a systematic "ascent" from the abstract to the concrete.

The experience in an extremely abstract sense is a struggle against the impossibility of living, it is in a sense a struggle against death within life. But, naturally, not everything that dies out or is exposed to any threat inside life requires experience, but only that which is essential, significant, and fundamental for a given form of life, which forms its internal necessities. If it were possible to isolate and describe individual life forms and establish laws inherent to them, or "principles," then it is obvious that these laws would determine not only the "normal" processes of life realization, but also extreme life processes, i.e. experiences processes. In other words, each form of life corresponds to a special type of experience, and if so, in order to find out the basic patterns of the processes of experience and to typologize them, it is necessary to establish the basic psychological patterns of life and to typologize "forms of life." The construction of such a general typology constitutes the immediate task of this section.

The concept of life and activity in the concept of A. N. Leontiev

To solve this problem, it is necessary first of all to analyze the category of life itself, as it appears from a psychological point of view. Within the framework of the activity approach, the analysis of this limit for the psychology category should be carried out (and already partly conducted by A. N. Leontiev (87)) in comparison with the category of activity that is central to this approach.

In the concept of A. N. Leontiev, the concept of activity for the first time (logically, not chronologically) appears in connection with the discussion of the concept of life in its most general biological meaning, “in its universal form” (ibid., P. 37), life as interactions of specially organized bodies "(ibid, p.27). The peculiarity of this interaction is, in contrast to the interaction in inanimate nature, in that it is a necessary condition for the existence of one of the interacting bodies (of a living body) and that it is active and objective in nature. Those specific processes that carry out such interaction are the processes of activity (ibid., P.39). "Activity is a molar, non-additive unit of life ..." (89, p.81). This definition of A. N. Leont'ev extends to the pre-psychic life, and to life mediated by mental reflection, and to human life mediated by consciousness. However, in the latter case, life can be understood in two ways, and, accordingly, two concepts of activity are different. When life is taken non-individualized, as an abstract human life in general, activity is seen as the essence of this life and the matter from which an individual being is woven. When life is viewed as a concrete, individualized, final life whole (given, for example, in biographical fixation), as "a combination, more precisely, a system of successive activities" (ibid.), The concept of "unit" in the application to the activity should be interpreted as "part": life as a whole consists of parts - activities. It is no longer about the activity "in general, the collective meaning of this concept" (ibid, p.102), but about a special or separate activity, "which meets a certain need, dies away as a result of meeting this need and is being reproduced again ... "(ibid.)

The central, key point in the concept of individual activity is the question of motive. This seemingly private matter is in fact decisive for the whole theory of activity, the nerve of this theory, which has thickened its basic ontological and methodological foundations. Therefore, it requires a detailed discussion.

The introduction of A. N. Leont'ev "the understanding of motive as that object (real or ideal), which induces and directs itself to the activity. Differs from the generally accepted one" (ibid.). It gave rise to a mass of critical responses, slightly “correcting” this idea or rejecting it in the root (8; 32; 44, etc.). The closest reason for such aversion is that this thesis is considered not as a meaningful abstraction, but as a generalization of empirically observable facts of the stimulation of activity, the truth of which can be verified by direct correlation with empiry. At the same time, of course, it is enough at least one fact that does not fit into the idea of the stimulation of activity by a subject that meets the need, so that this view is considered false or at least insufficient.

And there are many such facts. In fact, A.N. Leontiev objects, does this external object [ 29 ] itself, by itself, be able to induce the subject to act? Shouldn't he first perceive the object before that one (and therefore, not the object itself, but its mental image) can have a motivating effect on it? But the mental reflection of the subject is not enough to cause the activity of the subject. For this, the need that this object answers is still to be actualized, otherwise living beings, faced with the object of need, would each time start to satisfy it, regardless of whether there is a need at the moment or not, but this contradicts the facts. (44, p.110). Further, the objective aggravation of the need itself must be reflected in some form in the psyche, for otherwise the subject will not be able to give preference to any of the possible activities (33, 44). And finally, the last event in this series of reflections should be the linking of two mental images - the image of need and the image of the corresponding subject. Only after all this will the impulse occur, and the motivator will therefore be, not the object itself, but its meaning for the subject. So argue opponents A. N. Leontiev.

The conclusion from the above argument can be summarized in the following antithesis: the subject of the need is not capable of in itself to induce and direct the activity of the subject, i.e. is not the motive of the activity (8). Although a counter-argument can be advanced against this antithesis, which consists in pointing out facts of the so-called “field behavior” in which, it would seem, things themselves force a person to act, this counterargument does not solve anything. Firstly, it is purely logical: after all, the formula of A. N. Leontiev claims for validity, and "field behavior" is only one class of activity processes. Secondly, because the very "field behavior" can be interpreted in different ways, and one of the possible explanations for the mechanism of its motivation is that it begins to be carried out not under the action of the object itself, but as a result of its perception by the subject (and how could it be otherwise?), which, it is necessary to think, awakens the corresponding need, which, in turn, is expressed in the psyche, for example, in the form of a direct desire to master this object. It is only because of this whole chain of events that the activity is prompted. The illusion of the initiating self-sufficiency of an object is created by the concealment of its meaning (55).

But if the impulse, even in the case of “field behavior”, which seems to be most appropriate for the Leontief formula, on closer examination turns out to be mediated by various representations of the subject and need, then what can be said, for example, of behavior arising from a volitional decision or conscious calculation, the absence of direct prompting which is the subject of the need is obvious.

So, if we consider a formula that states that the motive of an activity is a subject that meets the needs of the subject, as an attempt to generalize the whole variety of empirical cases of stimulation of an activity, it turns out that it does not stand up to criticism.

But the fact of the matter is that this formula is of a completely different kind. She has completely different claims, a different logical status and other ontological grounds than those implicitly ascribed to her by the criticism presented. Namely: it does not claim to cover the whole empirical diversity of possible facts of stimulation of individual activity; by its logical nature it is an abstraction, and an abstraction of a rather high order, i.e. such a statement, from which there is still a long way of theoretical "ascent" to the concrete. The latter does not mean that this statement itself, before the "ascent", does not contain in itself some concrete truth; The formula under discussion, like any abstract law, coincides with a specific state of affairs, but only when certain conditions are met.

In order to establish what these conditions are, it is necessary to describe the ontology that underlies the theory of A. N. Leontiev’s activity and his understanding of motivation — an ontology that is in fact directly opposite to the ontology attributed to this understanding by its critics, within which it turns out to be untenable. These two ontologies can be conditionally named:

"The ontology of the life world" and "the ontology of an isolated individual" .

Within the last primary for the subsequent theoretical deployment, the situation is considered to include, on the one hand, a separate, isolated from the world being, and on the other - objects, more precisely things that exist "in themselves." The space between them, empty and empty, only separates them from each other. Both the subject and the object are thought to be originally existing and defined before and outside of any practical connection between them, as independent natural entities. The activity that will practically connect the subject and the object has yet to be: in order to begin, it must receive a sanction in the initial situation of the separation of the subject and the object.

This cognitive image is the basis of all classical psychology, is the source of its fundamental ontological postulates ("immediacy" (148), "conformity" (111; 112), the identity of consciousness and psyche, self-identity of the individual) and methodological principles.

The way the activity in the framework of the ontology of an “isolated individual” is understood is directly determined by the “conformity postulate” (111; 112), according to which any activity of the subject is individually adaptive. If a subject and an object (strictly speaking, an individual and a thing) are put into the initial ontological representation separately and independently of each other, then the “conformity” at the second step of the activity introduced into this field can be thought of based on one of two opposite mechanisms.

The first possibility, realized in cognitively oriented concepts, in its ultimate rationalistic expression comes down to the conviction that calculation is at the core of the act. And even the emotional transcription of this idea (feeling is at the core of the action) retains the main cognitive thesis: the activity is sanctioned by reflection (rational or emotional). Reflection precedes activity; the subject and the object are connected first by ideally carried out by the subject orientational procedures that reveal the value of the object, and only then the activity practically linking them is carried out. In this case, purposeful, arbitrary, and conscious activity of an adult is consciously or unconsciously used as a model for describing all and all behavioral processes.

The second possibility, characteristic of reflexology and behaviorism, is most clearly embodied in the radical behaviorism of BF Skinner. The “rationality” of behavior is explained here as follows. It is assumed that the subject has a form of response that was given to his individual experience, which were completely formed before and independently of any active contact with the environment, do not change during ontogenesis and, in this already prepared form, are only “emitted” by the organism into the environment. The "conformance" of the emerging from these motor "emissions" behavior is not explained by the fact that an individual, having achieved success in a given situation with a certain reaction, acts in a similar situation in the same way, "anticipating" the same result. The reaction always remains blind and accidental, there is no reason to ascribe to it an internal sense of purpose and the mediation of the mental connection of the subject connections of the situation. The mechanism of individual adaptation should be conceived by analogy with the adaptation of the species (243): reactions like mutations are accidentally beneficial or harmful to the organism, thereby changing the likelihood of their occurrence, and the behavior acquires a seemingly expedient character, in fact remaining a set of blind samples, from the inside " enlightened "reflection. Any subject here is thought on the model of an animal, and being at a fairly low evolutionary level. [ 30 ]

What kind of ontology opposes the gnosiological pattern of "subject - object", ontologized in classical psychology? This is the ontology of the "vital world". [ 31 ]

Only within the framework of this ontology can one understand the content and the actual place in the general psychological theory of A. N. Leontiev's activity of that idea of motivation, which was discussed above.

As activity itself is a unit of life , so the main moment constituting it — the subject of activity — is nothing but the unit of the world .

Here it is necessary to emphasize very persistently the significance of the fundamental distinction between an object and a thing, which is conducted by A. N. Leontiev. We must limit the concept of the subject, he writes. "Usually this concept is used in a twofold sense - as a thing standing in any relation to other things ... and in a narrower meaning - as something opposing (German Gegenstand), resisting (Latin objectum), then what an act (Russian. "subject"), i.e., something to which a living being refers specifically as the object of its activity — indifferently to external or internal activity (for example, the subject of food, the subject of labor, the subject of reflection, etc.) (87, p.39). The subject, therefore, is not just a thing lying outside the life circle of the subject, but a thing already included in being, already becoming a necessary moment of this being, already subjectified by the life process itself to any special ideal (cognitive, indicative, informational, etc.) .) mastering it.

To clarify the true theoretical meaning of the thesis that the real motive is the subject, it is necessary to understand that the ordinary "evidence" of separateness of a living being from the world can not serve as a starting ontological position, because we never find a living being before and outside its connection with the world . It was originally implanted into the world, connected with it by the material umbilical cord of its vital activity. This world, while remaining objective and material, is not, however, the physical world, i.e. the world, as it appears before the science of physics, which studies the interaction of things, it is the life world. The vital world is, strictly speaking, the sole motivator and source of the vital activity of the creature inhabiting it. Such is the initial ontological picture. When we, starting from it, begin building a psychological theory and isolate (abstracting) a separate activity as a “unit of life” of the subject, the object of activity appears within the framework of this abstraction not in its self-sufficiency and self-satisfaction, not a thing that represents itself but as a “unit” representing the life world, and it is precisely because of this representation that the subject acquires the status of a motive. To base the psychological theory on the statement that the motive of activity is a subject is to proceed from the conviction that life is ultimately determined by the world. На этой начальной фазе теоретического конструирования в мотиве еще не дифференцируются конкретные функции (побуждения, направления, смыслообразования), еще не идет речи о различных формах идеальных опосредований, участвующих в инициации и регуляции конкретной деятельности конкретного субъекта, это все появляется "потом", из этого нужно не исходить, к нему нужно приходить, "восходя" от абстрактного к конкретному.

По своему методологическому статусу разбираемое представление о мотиве и является такой абстракцией (точнее, компонентом ее), от которой это "восхождение" совершается.

Каким образом деятельность выводится из онтологии "изолированного индивида", из ситуации разъединенности субъекта и объекта – это мы уже показали. Теперь у нас есть все необходимое, чтобы установить условия выведения понятия деятельности из "витальной" онтологии. Эта задача может быть сформулирована с учетом сказанного выше следующим образом: каковы должны быть условия и характеристики жизненного мира, чтобы абстрактная идея деятельности как процесса, побуждаемого предметом потребности самим по себе, оказалась выполнимой, т.е. совпала бы с конкретным? [ 32 ]

Построение типологии "жизненных миров"

The first and foremost of these conditions is the simplicity of the vital world. Life, in principle, can consist of many interconnected activities. But it is quite possible to conceive a creature that has one single need, one single attitude to the world. The inner world of such a creature will be simple , his whole life will consist of one activity.

Для такого существа никакое знание о динамике собственной потребности не является необходимым. Дело в том, что потребность в силу своей единственности будет принципиально ненасыщаемой (ср.: 63), и потому всегда актуально напряженной: ведь процесс удовлетворения потребности совпадает у такого существа с жизнью, а стало быть, он психологически незавершим (хотя фактически он может, конечно, прекратиться; эта остановка, однако, была бы равнозначна смерти).

Если далее предположить, что внешний мир нашего гипотетического существа легок , т.е. состоит из одного-единственного предмета (точнее, предметного качества), образующего как бы "питательный бульон", в точности соответствующий по составу потребности индивида и находящийся в непосредственном контакте с ним, обволакивающий его, то для того, чтобы такой предмет мог побуждать и направлять деятельность субъекта, не требуется никакого идеального отображения его в психическом образе.

Простота внутреннего мира и легкость внешнего и составляют те искомые условия-характеристики жизненного мира, при которых обсуждаемая формула непосредственного побуждения деятельности предметом потребности самим по себе реализуется буквально. [ 33 ]

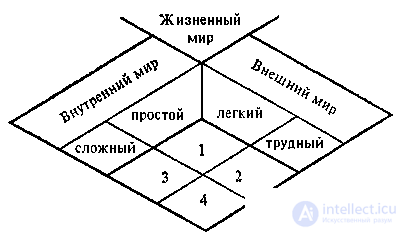

Дополнив характеристики простоты и легкости жизненного мира противоположными возможностями его сложности и трудности, получим две категориальные оппозиции, одна из которых (простой – сложный) относится к внутреннему миру, а другая (легкий – трудный) – к внешнему. Эти противопоставления задают типологию жизненных миров, или форм жизни, которая и была целью нашего рассуждения.

Структура этой типологии такова: "жизненный мир" является предметом типологического анализа. Он имеет внешний и внутренний аспекты, обозначенные соответственно как внешний и внутренний мир. Внешний мир может быть легким либо трудным. Внутренний – простым или сложным. Пересечение этих категорий и задает четыре возможных состояния, или типа "жизненного мира".

Типология жизненных миров

Прежде чем приступить к последовательной интерпретации полученной типологии, следует подробнее обсудить задающие ее категории.

В психологии понятию "жизненного мира", пожалуй, наибольшее внимание уделил К. Левин. Неудивительно, что для К. Левина, которого так волновала задача превращения психологии в строгую науку, построенную на принципах "галилеевского" мышления (215), главным в проблеме психологического мира [ 34 ] был вопрос о его замкнутости, т.е. наличии принципиальной возможности объяснения по его законам любой ситуации С1 из предшествующей ситуации С0 (или, наоборот, предсказания из всякой С0 последующей С1. Психологический мир, по мнению К. Левина, в отличие от физического, этому критерию не удовлетворяет и, следовательно, является открытым Другими словами, физический мир не имеет ничего внешнего: зная совокупную мировую ситуацию и все физические мировые законы, можно было бы (считает Левин) предсказать все дальнейшие изменения в этом мире, ибо ничто извне не может вмешаться в ход физических процессов, раз и навсегда определенных физическими законами За пределами же данного психологического мира существует внешняя, трансгредиентная ему реальность, которая воздействует на него, вмешиваясь в ход психологических процессов, и потому невозможно ни полное объяснение, ни предсказание событий психологического мира на основании одних только психологических законов. Если человек пишет письмо приятелю, приводит пример К. Левин (216), и вдруг открывается дверь и входит сам этот приятель, то эти две следующие друг за другом психологические ситуации стоят в таком отношении, что из первой ситуации невозможно ни предсказать, ни объяснить вторую.

Но не делает ли открытость психологического мира неправомерным само это понятие: что это за самостоятельный мир, если на события внутри него оказывают влияние процессы, не подчиняющиеся законам этого мира? Спасти понятие можно только, если удастся концептуализировать представление о мире, который динамически не замкнут, но внутри которого тем не менее имеет место строгий детерминизм (216). К Левин, решая эту проблему, предлагает математические представления, демонстрирующие возможность таких замкнутых областей, которые тем не менее подобно открытым областям соприкасаются с внешним пространством всеми своими точками как периферическими, так и центральными: это, например, плоскость, помещенная в 3-мерное пространство и вообще n-мерное пространство, помещенное в пространство (n+1)-мерное (там же).

Думается, однако, что такой формализм не решает проблемы, поставленной перед собой К. Левиным, – показать возможность строгого детерминизма внутри динамически незамкнутого психологического мира. Гораздо более важным является содержательное обсуждение вопроса Надо сказать, что в рассуждении К. Левина о физическом мире кроется одна существенная неточность, которая состоит в неявном отождествлении (несмотря на то что опасность его К. Левин сознает) физического мира со всей природой в целом, с мировым универсумом. Возникновение таких, несомненно обладающих физическим существованием вещей, как, например, архитектурные сооружения или биоценозы, хотя и может быть в принципе описано с точки зрения происходивших при этом физических процессов, но не может быть ни объяснено, ни тем более предсказано как необходимое на основании даже абсолютного знания всех физических законов, несмотря на то что последние при этом возникновении ни разу не нарушались. Следовательно, по введенному Левиным критерию "предсказуемости" и физический мир, точно так же, как и психологический, является открытым, т.е. и на него возможно влияние из нефизических сфер, закономерности которых не ухватываются физическим взглядом на реальность. Но это влияние осуществляется тем не менее целиком на физической почве, сообразно физическим законам, исключительно физическими средствами, и в этом смысле ввиду отсутствия в физическом мире нефизических чуждых ему явлений и событий он является замкнутым, не имеющим внешнего, ибо всякий иной, лишенный физического воплощения процесс не оставляет в нем следа, никак не затрагивает его.

И точно так же одновременно открытым и закрытым (замкнутым) является жизненный, психологический мир данного существа. Психологический мир не знает ничего непсихологического, в нем не может появиться ничего инородного, относящегося к иной природе. Однако в психологическом мире время от времени обнаруживаются особые феномены (в первую очередь трудность и боль), которые хотя и являются полностью психологическими и принадлежат исключительно жизненной реальности, но в то же время как бы кивают в сторону чего-то непсихологического, источником чего данный жизненный мир быть не мог. Через эти феномены в психологический мир заглядывает нечто трансцендентное ему, нечто "оттуда", но заглядывает оно уже в маске чего-то психологического, уже, так сказать, приняв психологическое гражданство, в ранге жизненного факта. И только своей тыльной стороной эти феномены настойчиво намекают на существование какого-то самостоятельного, инородного бытия, не подчиняющегося законам данного жизненного мира.

Подобного рода феномены могут быть условно названы "пограничными", они конституируют внешний аспект жизненного мира, как бы закладывают основу, на которой вырастает реалистичное восприятие внешней действительности.

Другими словами, феномены трудности и боли вносят в изначально гомогенный психологический мир дифференциацию внутреннего и внешнего, точнее, внутри психологического мира в феноменах трудности и боли проступает внешнее.

Нужно специально отметить, что, говоря о трудности внешнего мира, мы будем иметь в виду не только соответствующее переживание*, но и трудность как действительную характеристику мира; но, понятно, не мира самого по себе, не мира до и вне субъекта, а мира, так сказать, "деленного на субъекта", мира, видимого сквозь призму его жизни и деятельности, ибо трудность может быть обнаружена в мире не иначе, как в результате деятельности.

До сих пор мы рассуждали феноменологически, занимая позицию как бы внутри самой жизни и пытаясь увидеть мир ее глазами.. Из внешней же позиции "легкости" внешнего аспекта жизненного мира соответствует обеспеченность всех жизненных процессов, непосредственная данность индивиду предметов потребностей, а "трудности" – наличие препятствий их достижению.

By the inner aspect of the psychological world (or the inner world) is meant the inner structure of life, organization, conjoining and connectedness between its individual units. (At the same time, we are distracted from organic, natural, purely biological links between needs.) Although simplicity внутреннего мира ради удобства рассуждения вводилась нами и в дальнейшем в основном будет рассматриваться как его односоставность, фактически такой жизненный мир, состоящий из одной "единицы", является лишь одним из вариантов простого во внутреннем отношении мира. Простота, строго говоря, должна пониматься как отсутствие надорганической структурированности и сопряженности отдельных моментов жизни. Даже при наличии у субъекта многих отношений с миром его внутренний мир может оставаться простым в случае аморфной слитости его отношений в одно субъективно нерасчлененное единство либо в случае непроницаемой отделенности их друг от друга, когда каждое отдельное отношение реализуется субъектом так, как если бы оно было единственным. В первом случае психологический мир представляет собой целое без частей, во втором – части без целого.

These are the categories that define the types of “life worlds” we have obtained. Now it is necessary to dwell on one feature of the description of these types themselves. Each life world will be characterized first of all in terms of its space-time organization, i.e. described in terms of chronotope. Moreover, in accordance with the distinction between the external and internal aspects of the life world, we will separately describe the external and internal time-space, or, equivalently, the external and internal aspect of the integral time-space (chronotope) of the life world.

We introduce several conditional terms describing the chronotope. The external aspect of the chronotop will be characterized by the absence or presence of “ length ”, which consists in the spatial distance (objects of need) and the temporal duration necessary to overcome distance. It is clear that "length" is a projection of the concept of "difficulty" on the chronotopic plane, or, otherwise, the expression of this concept in the language of space-time categories: in fact, whatever the actual difficulties of life are - in the remoteness of goods, their concealment or the presence of obstacles - they are all unanimous in what they mean the absence of the possibility of directly meeting the needs, requiring the subject to make efforts to overcome them, and therefore they can be reduced to one conditional measure - “length”.

The internal aspect of the chronotop describes the structure of the inner world, i.e. the presence or absence of " contingency ", by which we understand the subjective unity of the various units of life. "Conjugation" is expressed in the connection between different life relations in the inner space. In the temporal aspect, "contingency" means the presence of subjective connections of the sequence between the realization of individual relations. So, the length, distance, duration, contingency, connectedness, consistency - all these are the terms of the language with which we will describe the chronotope of the life world.

And finally, the last preliminary remark. How should each type of typology be treated? And how - to display a certain slice of psychological reality, and how to a certain pattern of understanding. From the formal side, these schemes are strictly defined by the categories that define them and at the same time can be filled with lively phenomenological content. In combination, both makes them indispensable means of psychological thinking. Types are, as it were, living specimens, which themselves possessing an obvious phenomenological reality, by virtue of their categorical definiteness, can be effectively used in the cognitive function.

Comments

To leave a comment

Psychology of experience

Terms: Psychology of experience