Lecture

The scientific direction "Artificial Intelligence" originated in the general complex of cybernetic research. The development of computer technology, the intensive improvement of programming associated with it, the expansion of computer use, and the presence of a very superficial analogy between the structure of a computer and the structure of the human brain led to the emergence of two directions in research on artificial intelligence.

The first - let's call it software-pragmatic - was engaged in creating programs that could be used to solve those tasks whose solution was previously considered exclusively by the person’s prerogative (recognition programs, simple game programs, programs for solving logical problems, searching, classification, etc. .).

The second, which can be called bionic, was interested in the problems of artificially reproducing those structures and processes that are characteristic of the living human brain and which underlie the process of solving problems by man. This direction has a clearly expressed fundamental character, and its intensive development is impossible without simultaneous in-depth study of the brain by neurophysiological, morphological and psychological methods.

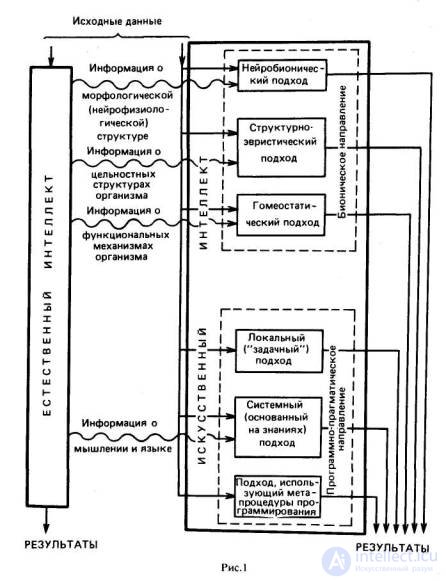

The general structure of research in artificial intelligence can be represented by the scheme shown in Fig. 1. In the bionic direction there are three different approaches.

The first is neurobionic. It is based on systems of neural-like elements, from which systems are created that are capable of reproducing certain intellectual functions. Among the tasks that, apparently, can be solved in the framework of this approach, include multi-channel (parallel) recognition of complex visual images, training in conditioned reflexes, etc.

The second approach is structural heuristic. It is based on knowledge of the observed behavior of an object considered as a black (rather, gray) box, and considerations about those structures (and their properties) of the brain that could ensure the implementation of the observed forms of behavior.

Finally, the third approach, which has been developing intensively lately, is homeostatic. In this case, the brain is considered as a homeostatic system, which is a combination of opposing (and cooperating) subsystems, as a result of the functioning of which the necessary balance (stability) of the entire system is ensured in conditions of constantly changing environmental influences. Homeostatic models confirm the viability of this approach. However, at present there are still no homeostatic modules that could be considered as universal elements for the creation of intelligent systems.

Due to the complexity of the goals and objectives of the bionic direction, the program-pragmatic direction is now dominant in artificial intelligence. This approach does not raise the question of the adequacy of the structures and methods used by those used by people in similar cases, but only the final result of solving specific problems is considered. Note that in some cases, when solving intellectual problems, some bionic considerations are applied, but not them, but the final result plays a decisive role.

In the program-pragmatic direction, one can also distinguish three approaches.

The first approach - local or "task" - is based on the point of view that for each task inherent in human creative activity, you can find a way to solve it on a computer, which, when implemented as a program, will produce a result or a similar result obtained by a person or even the best. Developed many skillful programs of this kind. A typical example is chess programs that play chess better than most people, but they are based on ideas that are far from those used by people in the game.

The second approach, systemic or knowledge-based, is associated with the idea that the solution of individual creative tasks does not exhaust all the problems of artificial intelligence. The natural intelligence of a person is capable of not only solving creative tasks, but if necessary learning one or another kind of creative activity. Therefore, artificial intelligence programs should be focused not only or not so much on solving specific intellectual problems, but on creating tools that allow you to automatically build programs for solving intellectual problems when such programs arise. This approach is currently central to the program-pragmatic direction.

The third approach considers the problems of creating intelligent systems as part of a general programming theory (as some kind of new development in this theory). In this approach, ordinary software tools are used to compile intelligent programs that allow writing the necessary programs based on task descriptions in professional natural language. All meta-means that arise on the basis of a partial analysis of natural intelligence are considered here only from the point of view of creating intelligent software, i.e., a set of tools that automate the activities of the programmer himself.

From the point of view of the final result, four major sections are distinguished in the program-pragmatic direction (Fig. 2).

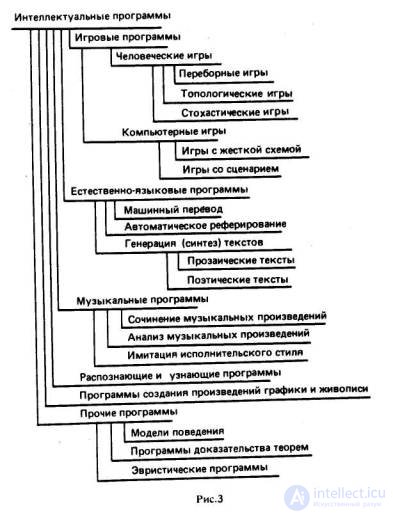

Intellectual programs are divided into several groups and subgroups defined by the types of tasks solved by these programs (Fig. 3). A common feature of gaming programs is the extensive use of search procedures and methods for solving enumerated problems associated with searching and viewing a large number of options. These methods are used in computer-aided solution of game problems, in problems of decision making, in planning expedient activities in intelligent systems.

Natural language programs, the development of which began with the tasks of machine (automatic) translation, use the results and methods of artificial intelligence, methods of general linguistics and formal (structural or mathematical) linguistics. This combination has opened up broad opportunities for the formal study of natural language, the automation of morphological, syntactic, lexical and in many ways semantic analysis of sentences in natural language, as well as analysis of a coherent text.

The remaining groups of programs are more specific. Note that they are largely associated with the formation of general views on the nature of creative processes and their modeling. These studies have a significant impact on those sections of artificial intelligence, which use a number of psychological results in solving problems.

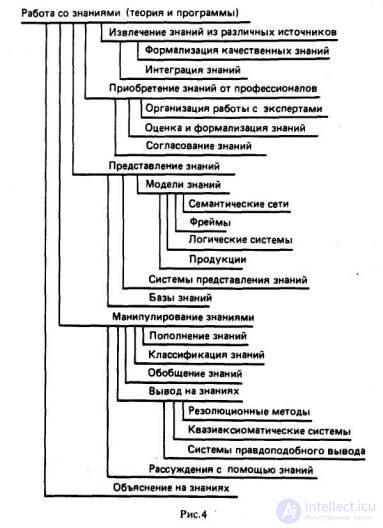

Working with knowledge is the basis of the modern period of development of artificial intelligence. In fig. 4 shows the structure of this direction. Any subject (problem) area of activity can be described as a set of information about the structure of this area, its main characteristics, the processes taking place in it, as well as ways to solve problems arising in it. All this information forms knowledge of the subject area. To solve problems in this subject area, it is necessary to gather knowledge about it and create a conceptual model of this area. Sources of knowledge can be documents, articles, books, photos and more.

From these sources it is necessary to extract the knowledge contained in them. This process is quite difficult, because it is necessary to assess in advance the importance and necessity of certain knowledge for the operation of the intellectual system. Specialists who deal with issues related to knowledge, are called knowledge engineers or knowledge engineers.

In the field of knowledge extraction, there are two main sections: formalization of high-quality knowledge and integration of knowledge. The first is associated with the creation of methods that allow you to move from knowledge, expressed in textual form, to their counterparts, suitable for entering into the memory of an intelligent system.

In connection with this problem, not only traditional methods of processing experimental data were developed, but also a new direction, called fuzzy mathematics. Fuzzy mathematics and its methods have had a significant impact on many areas of artificial intelligence, and in particular on the whole range of problems associated with the presentation and processing of high-quality information.

When a knowledge engineer obtains knowledge from various sources, he must integrate it into some interconnected and consistent system of knowledge about the subject area. The problem of the integration of knowledge is not yet so acute, but it is already clear that without this solution it would hardly be possible to create an idea of a subject area that has the same rich nuances that exist among specialists.

The knowledge contained in the sources of information alienated from the specialist, as a rule, is not enough. These specialists cannot express a significant part of their professional experience verbally. Such knowledge is often called professional skill or intuition. In order to acquire such knowledge, we need special techniques and methods. They are used in instrumental systems for the acquisition of knowledge, the creation of which is one of the tasks of knowledge engineering.

The knowledge gained from experts should be assessed in terms of their compliance with previously accumulated knowledge and formalized for entering into the system’s memory. In addition, the knowledge gained from various experts must be coordinated with each other. It is not uncommon for this knowledge to be outwardly incompatible and even contradictory. A knowledge engineer should eliminate these contradictions by interviewing experts.

The next big problem is the representation of knowledge in the memory of the system. For this purpose various models of knowledge representation are developed. Currently, four basic knowledge models are used in intelligent systems. The first model is probably the closest to how knowledge is represented in natural language texts. It is based on the idea that all the necessary information can be described as a set of triples of the form ( arb ) , where a and b are two objects or concepts, and r is a binary relation between them. Such a model can be represented graphically in the form of a network in which the vertices correspond to objects or concepts, and the arcs represent relations between them. The arcs are labeled with the names of the corresponding relationship. This model is called the semantic network.

Semantic networks, depending on the nature of the relations allowed in them, have a different nature. In situational management, these relations mainly described temporal, spatial, and causal relations between objects, as well as the results of impacts on objects by the control system. In systems of planning and automatic program synthesis, these relations are connections of the type “goal-means” or “goal-subgoal”. In the classifying systems, relations convey connections for the inclusion of volumes of concepts (of the type "genus-species", "class-element", etc.). The so-called functional semantic networks are also common, in which arcs characterize connections of the form "argument-function". Such networks are used as models of computational processes or models of discrete devices.

Thus, semantic networks are a model of a wide purpose. The theory of semantic networks is not yet complete, which attracts the attention of specialists working in the field of artificial intelligence.

With different syntactic restrictions on the structure of the semantic network, more rigid types of representations arise. For example, relational representations characteristic of relational databases, or causal representations in logic, which are widely used in machine methods of logical inference or in logical programming languages such as the Prolog language.

Frame representations of knowledge in a certain sense are also a type of semantic networks, for the transition to which it is necessary to satisfy a number of restrictions of a syntactic nature. Artificial intelligence has transformed the meaning of the concept of "frame". This concept was introduced by M.Minsky, who under the frame of an object or phenomenon understood its minimal description, which contains all the essential information about this object or phenomenon and has the property that removing any part from the description leads to the loss of essential information, without which the description of the object or phenomenon may not be sufficient to identify them. Later, this interpretation of the concept of "frame" has changed. Frames began to be understood as descriptions of the form “Frame Name (Multiple Slots).” Each slot is a pair of the form (Slot Name. Slot Value). It is allowed for the slot itself to be a frame. Then many slots are used as slot values. To fill slots, constants, variables, any valid expressions in the selected knowledge model, references to other slots and frames, etc. can be used. Thus, the frame is a flexible design that allows you to display in the memory of an intelligent system a variety of knowledge.

Two other common knowledge models are based on the classical logical model of inference. These are either logical calculus of the type of predicate calculus and its extensions, or a system of products defining the elementary steps of transformations or conclusions. These two knowledge models are distinguished by a pronounced procedural form. Therefore, it is often said that they describe procedural knowledge, and knowledge models based on semantic networks, declarative knowledge. Both kinds of knowledge can coexist with each other. For example, products may act as values of some slots in a frame. It is these mixed representations that are now in the center of attention of researchers.

The listed models of knowledge have arisen as if forcibly in artificial intelligence. They do not rely on analogs of cognitive structures to represent the knowledge people use. This is due to poor knowledge of the forms of knowledge representation in humans. The relevant section of psychology - cognitive psychology did not arise without the influence of research in the field of artificial intelligence. And although this branch of psychology is developing rapidly, its results, which could have an impact on the creation of new models of knowledge, are still too modest.

In intelligent systems for storing and using knowledge, special knowledge representation systems are created, including a set of procedures necessary to record knowledge, retrieve it from memory and maintain knowledge in working condition. Knowledge representation systems are often framed as knowledge bases that are the natural development of databases. It is in them that the main procedures for manipulating knowledge are currently concentrated.

Among these procedures can be noted procedures for the replenishment of knowledge. All human knowledge contained in the texts is fundamentally incomplete. Perceiving texts, we kind of replenish them with the information that we know and which is relevant to this text (relevant to it). Similar procedures should occur in knowledge bases. New knowledge entering them should, together with the information that has already been recorded in the database, form an extension of the knowledge received. Among these procedures, a special place is occupied by pseudo-physical logics (time, space, actions, etc.), which, based on the laws of the external world, supplement the information coming into the knowledge bases.

Knowledge in intelligent systems is not stored haphazardly. They form ordered structures, which facilitates the search for the necessary knowledge and the maintenance of knowledge bases. For this purpose, various classification procedures are used. Types of classifications can be different: genera of the type “part-whole” or situational, when knowledge that is relevant to a typical situation is combined into one set. In this area, research in artificial intelligence is closely related to the theory of classification, which has long existed as an independent branch of science.

In the process of classification, abstraction often occurs from individual elements of descriptions, from separate fragments of knowledge about objects or phenomena, and generalized knowledge appears. A generalization can take several steps, which ultimately leads to abstract knowledge, for which there is no direct prototype in the external world. Манипулирование абстрактными знаниями повышает интеллектуальные возможности систем, делая эти манипуляции общими по своим свойствам и результатам.

Вывод на знаниях зависит от модели, которая используется для их представления. Если в качестве представления используются логические системы или продукции, то вывод на знаниях становится близок к стандартному логическому выводу. Это же происходит при представлении знаний в каузальной форме. Во всех этих случаях в интеллектуальных системах используются методы вывода, опирающиеся на идеи метода резолюций или на идеи обратного вывода Маслова (как в языке Пролог при каузальной форме представления).

Основное отличие баз знаний и баз данных интеллектуальных систем от тех объектов, с которыми имеет дело формальная логическая система, это их открытость. Возможность появления в памяти интеллектуальной системы новых фактов и сведений приводит к тому, что начинает нарушаться принцип монотонности, лежащий в основе функционирования всех систем, изучаемых традиционной математической логикой. Согласно принципу монотонности, если некоторое утверждение выводится в данной системе, то никакие дополнительные сведения не могут изменить этот факт. В открытых системах это не так. Новые сведения могут изменить ситуацию, и сделанный ранее вывод может стать неверным.

Немонотонность вывода в открытых системах вызывает немалые трудности. В последнее десятилетие сторонники логических методов в искусственном интеллекте делают попытки построить новые логические системы, в рамках которых можно было бы обеспечить немонотонный вывод. Но на этом пути пока мало результатов. И дело не только в немонотонности вывода. По сути системы, с помощью которых представляются знания о предметных областях, не являются строго аксиоматическими, как классические логические исчисления. В последних аксиомы описывают извечные логические истины, верные для любых предметных областей. А в интеллектуальных системах каждая предметная область использует свои, специфические, верные только в ней утверждения. Поэтому и системы, которые возникают при таких условиях, следует называть квазиаксиоматическими. В таких системах вполне возможна смена исходных аксиом в процессе длительного вывода и, как следствие, изменение этого вывода.

И наконец, еще одна особенность вывода на знаниях - неполнота сведений о предметной области и протекающих в ней процессах, неточность входной информации, неполная уверенность в квазиаксиомах. А это означает, что выводы в интеллектуальных системах носят не абсолютно достоверный характер, как в традиционных логических системах, а приближенный, правдоподобный характер. Такие выводы требуют развитого аппарата вычисления оценок правдоподобия и методов оперирования ими. В настоящее время рождается новая теория вывода, в которую лишь как небольшая часть входит достоверный вывод.

В интеллектуальных системах специалисты стремятся отразить основные особенности человеческих рассуждений, опыт специалистов, которые обладают профессиональными умениями, пока не полностью доступными искусственным системам. Вывод - всего лишь одна из форм того, как человек приходит к нужным ему заключениям.

Другими формами рассуждений человека являются аргументация на основе имеющихся знаний, рассуждения по аналогии и ассоциации, оправдание заключения в системе имеющихся прагматических ценностей и многое другое, чем люди пользуются в своей практике. Внесение всех этих приемов в интеллектуальные системы сделает их рассуждения более гибкими, успешными и человечными.

Для того чтобы согласиться с некоторым мнением, необходимо знать допущения, которые лежат в его основе. Если они неизвестны, то можно попросить оппонента объяснить, как он пришел к своему мнению. Аналогичная функция возникла и в интеллектуальных системах. Поскольку они принимают решения, опираясь на знания, которые могут быть неизвестны пользователю, решающему свою задачу с помощью интеллектуальной системы, то он может усомниться в правильности полученного решения. Интеллектуальная система должна обладать средствами, которые могут сформировать пользователю необходимые объяснения. Объяснения могут быть различного типа - касаться процесса получения решений, оснований, которые были для этого использованы, способов отсечения альтернативных вариантов и т.п. Все это требует развитой теории объяснений.

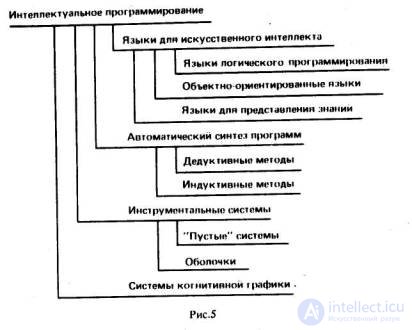

В основе интеллектуального программирования (рис.5) лежит создание инструментария, ориентированного на поддержку разработки интеллектуальных программ систем.

Лишь небольшая часть языков программирования ориентирована на задачи искусственного интеллекта. Так, наиболее распространенный язык Лисп отражает ту точку зрения, что основой большинства интеллектуальных задач являются хорошо организованные перебор и поиск. Увеличение крена в область задач логического вывода породило язык Пролог.

Представление о том, что процедуры логического вывода в задачах искусственного интеллекта должны быть дополнены новой конструкцией, в основе которой лежит объект с его свойствами и признаками, привело к появлению так называемых объектно-ориентированных языков, среди которых наиболее известен Смолток. При этом решение задач представляется как манипулирование с понятиями, обобщающими объекты, которые связаны с проблемной областью.

Развитие методов работы со знаниями и форм представления знаний привело к появлению специальных языков представления знаний, например языков KL, KRL, FRL, ориентированных на фреймовое представление, и языка Пилот, в основе которого лежит продукционная модель знаний.

Типично программистский характер имеют и работы по автоматизации программирования. Синтез программ может быть осуществлен из типовых блоков (готовых модулей) по описанию исходной задачи в рамках некоторой дедуктивной системы. В этом случае процедура синтеза представляет собой нечто вроде логического вывода, в ходе которого программа как бы "извлекается" из траектории вывода. Другой вид синтеза - индуктивный - представляет собой процесс генерирования программы в ходе обучения на множестве примеров. Основной трудностью здесь является выбор способа формального описания функциональных особенностей и свойств синтезируемых программ.

Своеобразным развитием систем автоматизации программирования являются инструментальные системы. Под инструментальными системами обычно понимают совокупность программных и частично аппаратных средств, предназначенных для относительно быстрого проектирования и создания разнообразных интеллектуальных систем. К числу подобных инструментальных средств относятся лингвистические процессоры, системы анализа и синтеза речи, базы данных, базы знаний, системы машинной графики и другие крупные модули, которые могут быть использованы в различных интеллектуальных системах.

Были созданы специальные инструментальные средства тиражирования однотипных интеллектуальных систем, например система-прототип, называемая "пустой", в которой заранее зафиксированы все средства заполнения базы знаний и манипулирования знаниями в ней, но сама база знаний не заполнена. Для настройки такой "пустой" системы на некоторую предметную область нужно, используя готовую форму представления знаний, ввести в базу знаний необходимую информацию о предметной области, превращая тем самым систему-прототип в готовую интеллектуальную систему. К сожалению, область использования "пустых" систем оказалась весьма ограниченной, так как даже для, казалось бы, однотипных предметных областей требуется модификация средств манипулирования знаниями, а иногда и форм представления знаний.

Дальнейшим этапом в развитии систем-прототипов является переход к системам, называемым "оболочками", позволяющим в ходе перехода от них к конкретным системам широко варьировать как формы представления знаний, так и способы манипулирования ими. Несмотря на то, что создание систем-оболочек требует больших затрат, они оказываются эффективными.

Новым специфическим разделом интеллектуального программирования являются системы когнитивной графики, которые пытаются реализовать основную идею современного представления о мышлении как о синтезе визуальных и символьных представлений о внешнем мире.

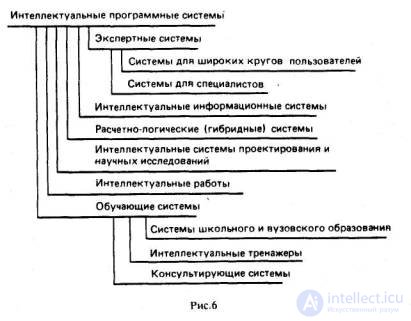

Все виды интеллектуальных программных систем (рис. 6) представляют собой практический выход программно-прагматического направления и предназначены для решения прикладных задач.

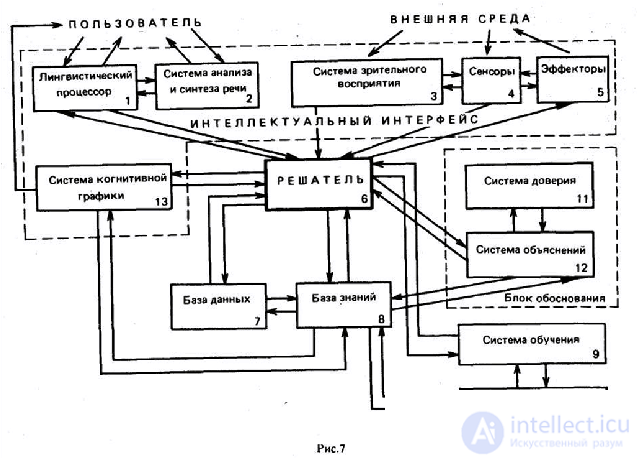

Общая структура интеллектуальной программной системы изображена на рис.7. Система содержит 13 функциональных блоков, часть которых может быть объединена в функциональные группы. Одной такой группой является интеллектуальный интерфейс, обеспечивающий эффективную связь всей системы с пользователем и внешней средой.

В состав интеллектуального интерфейса могут входить блоки 1-4 и 13. Лингвистический процессор обеспечивает связь пользователя с системой на естественном (почти всегда ограниченном) языке: ввод и понимание системой текстов на нем и вывод текстов, вырабатываемых системой.

Для голосового общения пользователя с системой используется система анализа и синтеза речи. Информация от внешней среды воспринимается системой с помощью сенсоров, представляющих собой аппаратно реализуемые чувствительные элементы. При этом зрительная информация перед поступлением в систему обрабатывается в системе зрительного восприятия. Если система имеет возможность воздействовать на внешнюю среду, то в состав интеллектуального интерфейса должен быть включен блок эффекторов. Система когнитивной графики позволяет пользователю воспринимать результаты работы системы в графической форме и общаться с ней на языке графики.

Таблица.

|

Вид интеллектуальной системы |

Номер блока |

|||||||||||

|

one |

2 |

3 |

four |

five |

6 |

7 |

eight |

9 |

ten |

11 и 12 |

13 |

|

|

Expert |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

0 |

0 |

+ |

0 |

|

Informational |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Расчетно-логическая (гибридная) |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

0 |

+ |

- |

+ |

|

Проектирование научных исследований |

+ |

- |

0 |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

0 |

+ |

|

Обучающая |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

|

Интеллектуальные роботы |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

0 |

+ |

0 |

0 |

Центральным блоком интеллектуальной системы является решатель - вычислительная система, состоящая из одной или нескольких ЭВМ (процессоров), связанная с базами данных и знаний, а также с остальными блоками системы. Целенаправленная работа системы обеспечивается системой планирования, хранящей априорно введенные цели, а также запоминающей новые цели, полученные с помощью системы обучения. Последняя участвует также в формировании новых знаний, возникающих в ходе анализа взаимодействия интеллектуальной системы с внешней средой. Группа блоков обоснования, включающих систему объяснения и систему доверия, служит для обоснования полученных системой решений (если пользователь интересуется этим) с привлечением информации, содержащейся в базе знаний.

Заметим, что все перечисленные блоки, за исключением блоков 4 и 5, могут быть реализованы как на специальных аппаратных средствах, так и в решателе с использованием его логико-вычислительных возможностей. Кроме того, в зависимости от степени развития и функциональных возможностей конкретных интеллектуальных систем в их структуру часть перечисленных блоков может не входить.

Для установления соответствия между конкретными функциональными структурами основных типов интеллектуальных систем, представленных на рис.6, и типовой схемой рис.7 рассмотрим таблицу. В ней для каждого вида интеллектуальной системы показано, какие блоки в этот вид обязательно входят ( + ) и какие блоки не входят (-). Нулями отмечены блоки, которые могут входить или не входить в соответствующую систему в зависимости от характера решаемых задач и степени технического совершенства системы.

При описании современного состояния работ в области искусственного интеллекта мы старались по возможности не останавливаться на отдельных деталях, имея в виду, во-первых, быстрое развитие этой области, существенно опережающее ее терминологию, а во-вторых, то, что дополнительную информацию об этом можно получить из текста словаря.

М. Г. Гаазе-Рапопорт

YES. Pospelov

BASIC RUBRICATOR ON ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

|

THEORY AND METHODOLOGY OF AI |

10,000 |

|

GENERAL PROBLEMS OF AI |

11,000 |

|

METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS OF AI |

11,100 |

|

PHILOSOPHICAL PROBLEMS OF AI |

11200 |

|

SOCIAL PROBLEMS OF AI |

11300 |

|

KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING |

12,000 |

|

COMPUTER LOGIC |

13,000 |

|

DEDUCTIVE CONCLUSION |

13,100 |

|

RESOLUTION METHOD |

13200 |

|

AUTOMATIC PROOF OF THEOREM |

13300 |

|

FORMATION OF NOTIONS AND INDUCTIVE CONCLUSION |

13400 |

|

NON-CLASSICAL LOGICS |

13500 |

|

TRUSTING OUTLET |

13600 |

|

CONCLUSION ON THE BASIS OF INCOMPLETE, FUZZY AND UNCERTAIN INFORMATION |

13600 |

|

CONCLUSION ON THE BASIS OF ANALOGY, HEALTHY MEANING |

13600 |

|

COMPUTER LINGUISTICS |

14,000 |

|

MODELS "MEANING-TEXT", "FIGURE-TEXT" |

14100 |

|

ANALYSIS OF TEXTS |

14200 |

|

TEXT PROCESSING, SYNTHESIS OF RELATED TEXTS |

14300 |

|

MACHINE TRANSLATE |

14,400 |

|

USER INTERFACE |

14,500 |

|

DISCOURSE MODELS AND EXPLANATION SYSTEMS |

14600 |

|

COGNITIVE PSYCHOLOGY |

15,000 |

|

MODELS OF THE KNOWLEDGE OF HUMAN |

15100 |

|

HUMAN INFORMATION PERCEPTION MODELS |

15100 |

|

MODELS OF THE ORGANIZATION OF MEMORY IN HUMAN |

15100 |

|

MODELS OF DECISION-MAKING AND HUMAN BEHAVIOR |

15200 |

|

MODELS OF HUMAN RESEARCH AND CONCLUSION |

15200 |

|

MANAGEMENT OF MANAGEMENT |

15300 |

|

PSYCHOLOGICAL MODELS OF USERS OF COMPUTERS |

15400 |

|

INFORMATION PERCEPTION MODELS IN AI SYSTEMS |

16,000 |

|

PERCEPTION OF VISUAL AND HEARING INFORMATION |

16,100 |

|

RECOGNITION OF SPEECH AND IMAGES |

16200 |

|

ANALYSIS OF THREE-DIMENSIONAL SCENES |

16300 |

|

LANGUAGES AND MODELS FOR DESCRIPTION OF IMAGES |

16400 |

|

SYNTHESIS OF SPEECH COMMUNICATIONS |

16,500 |

|

FORMATION OF SOLUTIONS IN AI SYSTEMS |

17,000 |

|

MODELS OF SEARCH AND DECISION MAKING |

17100 |

|

FUZZY SETS AND ALGORITHMS IN DECISION-MAKING MODELS |

17200 |

|

FORMATION OF HYPOTHESES AND HEURISTIC ALGORITHMS FOR DECISION-MAKING |

17300 |

|

INTELLIGENT PLANNERS AND PROBLEM SOLVERS |

17400 |

|

AUTOMATIC PROGRAM SYNTHESIS |

17,500 |

|

TRAINING AND SELF-LEARNING |

18,000 |

|

MODELS OF TRAINING AND SELF-LEARNING |

18,100 |

|

INTELLIGENT TRAINING SYSTEMS AND SIMULATORS |

18200 |

|

SELF-LEARNING SYSTEMS |

18300 |

|

SOFTWARE AND SOFTWARE FOR LEARNING AND SELF-TRAINING SYSTEMS |

18400 |

|

MODELING OF CREATIVE PROCESSES IN AI SYSTEMS |

19,000 |

|

MODELING GAME BEHAVIOR |

19,100 |

|

CREATING MUSICAL, LITERATURE AND PAINTING WORKS |

19200 |

|

SOLUTION OF CREATIVE TASKS IN SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, ETC. |

19300 |

|

INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS |

20,000 |

|

INTELLIGENT INFORMATION-SEARCH SYSTEMS |

21,000 |

|

DESIGN LOGIC SYSTEMS |

22,000 |

|

EXPERT SYSTEMS |

23,000 |

|

SYSTEMS FUNCTIONING ON THE BASIS OF RULES |

23,000 |

|

CLASSIFICATION ES |

23,100 |

|

EC, FUNCTIONING ON THE BASIS OF KNOWLEDGE |

23110 |

|

ES, FUNCTIONING ON THE BASIS OF IMAGES |

23120 |

|

HYBRID ES |

23140 |

|

COMPOSITION ES |

23200 |

|

KNOWLEDGE BASE |

23210 |

|

WORKING MEMORY |

23211 |

|

MODULE OF HEURISTIC KNOWLEDGE |

23212 |

|

MODULE OF ALGORITHMIC KNOWLEDGE |

23213 |

|

BASE OF FACTS |

23214 |

|

BASE RULES |

23215 |

|

METABLIC |

23215 |

|

MODEL BOARDS ANNOUNCEMENTS |

23216 |

|

OBJECT-ORIENTED APPROACH |

23217 |

|

MACHINE OUTPUT |

23220 |

|

MECHANISM OF CONCLUSION |

23221 |

|

MODULE OF APPROX DISCUSSION |

23230 |

|

USER INTERFACE |

23240 |

|

Subsystem of explanations |

23250 |

|

LANGUAGE REQUEST |

23260 |

|

KNOWLEDGE ACQUISITION SUBSYSTEM |

23270 |

|

SOFTWARE AND HARDWARE AI |

30,000 |

|

SOFTWARE AI |

31,000 |

|

LANGUAGES AI |

31100 |

|

SYMBOL LANGUAGES |

31110 |

|

Lisp |

31111 |

|

LANGUAGES OF LOGICAL TYPE |

31120 |

|

PROLOG |

31121 |

|

OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGES |

31130 |

|

SMOLTOLK |

31131 |

|

FLAVOR |

31132 |

|

LANGUAGES OF KNOWLEDGE |

31140 |

|

KRL |

31141 |

|

FRL |

31142 |

|

SRL |

31143 |

|

SHELL EN |

31200 |

|

SHELLS OF THE FIRST GENERATION (ONE METHOD OF KNOWLEDGE REPRESENTATION) |

31210 |

|

EMYCIN |

31211 |

|

EXPERT |

31212 |

|

M1 |

31213 |

|

HEARSAY-3 |

31214 |

|

KAS |

31215 |

|

PROSPECTOR |

31216 |

|

KL-ONE |

31217 |

|

SHELLS OF THE SECOND GENERATION (SEVERAL METHODS OF KNOWLEDGE REPRESENTATION) |

31220 |

|

KEE |

31221 |

|

ART |

31222 |

|

GOLD WORKS |

31223 |

|

PERSONAL CONSULTANT PLUS |

31224 |

|

PROTON |

31225 |

|

OPERATING SYSTEMS |

31300 |

|

UNIX |

31310 |

|

MS-DOS |

31320 |

|

HARDWARE AI |

32,000 |

|

HARDWARE TOOLS OF SERIAL ARCHITECTURE |

32100 |

|

SYMBOL COMPUTERS |

32110 |

|

LISP MACHINES |

32111 |

|

PROLOG MACHINES |

32112 |

|

REFAL MACHINES |

32113 |

|

INTELLIGENT WORKSTATIONS |

32120 |

|

SUN |

32121 |

|

APPOLO |

32122 |

|

PERQ |

32123 |

|

Vax |

32124 |

|

HARDWARE TOOLS OF PARALLEL ARCHITECTURE |

32200 |

|

COMMUNICATION MACHINES |

32210 |

|

PERSPECTIVE APPARATUS |

32300 |

|

NEUROCOMPUTERS |

32310 |

|

TRANSPUTERS |

32320 |

|

FULL COMPUTERS |

32330 |

|

SPECIAL PROCESSORS |

32400 |

|

SPECIAL PROCESSORS KNOWLEDGE BASES |

32410 |

|

SPECIAL PROCESSORS OF LOGICAL CONCLUSION |

32420 |

|

INTELECTUAL INTERFACE SPETSPROCESSORA |

32430 |

|

APPLICATION FIELDS |

40,000 |

|

DIAGNOSTICS |

41,000 |

|

MEDICAL DIAGNOSTICS |

41100 |

|

INTERPRETATION OF DATA |

42,000 |

|

CONTROL |

43,000 |

|

PREDICTION |

44000 |

|

PLANNING |

45,000 |

|

DESIGN |

46,000 |

|

CONTROL |

47,000 |

|

DYNAMIC OBJECT MANAGEMENT |

47100 |

|

MANAGEMENT OF TECHNOLOGICAL PROCESSES |

47200 |

|

BUSINESS |

48000 |

|

MARKET RESEARCH |

48100 |

|

TRAINING AND SIMULATORS |

49,000 |

Dictionary of Artificial Intelligence / Authors-compilers A.N. Averkin, M.G. Haase-Rapoport, D.A. Pospelov. M .: Radio and communication, 1992. –256s.

Comments

To leave a comment

Artificial Intelligence. Basics and history. Goals.

Terms: Artificial Intelligence. Basics and history. Goals.