Lecture

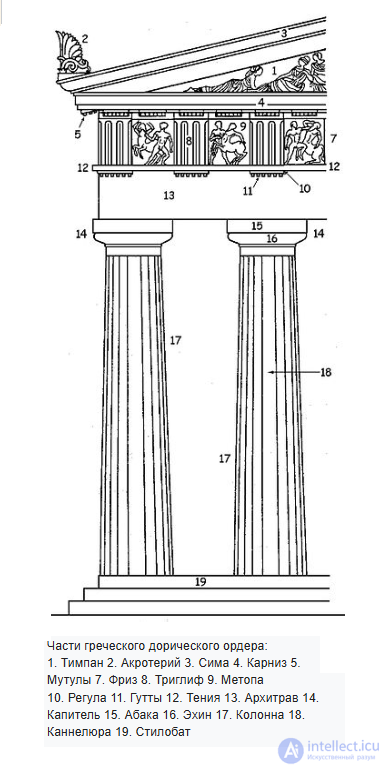

Composition in material architecture is a way of arranging architectural elements to create a holistic and harmonious image. It represents the unity of form and content, arising due to the artistic interpretation of the structural basis of the building. A striking example is the architectural order - it embodies not only the post-and-beam system, but also rethinks any structural principles, giving the structure strength and stability in artistic form.

Parts of the Greek Doric order

The choice of architectural composition is determined not only by aesthetic preferences or artistic approaches. It is formed under the influence of many factors: functionality, economic efficiency, ease of use, social and communication requirements, as well as specific conditions - such as natural features, construction technologies and the customer's wishes. The architectural appearance of an object primarily depends on the method of forming the form, which is determined by both material and technical aspects and visual settings. At the same time, the form itself retains its objective qualities, although its perception may change depending on the observation conditions.

This type of composition is built around the basic principle of forming a form through its three-dimensional structure. Here, volume is the main component.

Spatial composition

This approach involves working with a space that can be fully or partially limited. An example would be a room, hall or indoor arena where a single interior space is created.

The continuation of the idea of spatiality is realized through the unification or division of several spaces, creating the effect of depth in visual perception. A typical example is the enfilade arrangement of rooms. This type of composition covers not only interior zones, but also external open areas, which are partially framed by structural elements.

A complex form that arises from a combination of volumetric masses and spatial fragments. For example, a building in the shape of the letter U, where the courtyard is united with the surrounding buildings, or an object with a portico that combines the volume with the surrounding space.

Characterized by the fact that the perception of the architectural form is oriented toward the main point of view, usually the facade. In this case, the structure is organized along horizontal and vertical axes, and depth plays a secondary role. However, three-dimensional objects can also have a frontal structure - the main thing here is how they are perceived by the viewer.

The main feature is the predominance of height over area dimensions. In historical architecture, it is often manifested by dividing the structure into tiers, where with an increase in the overall height, the elements become less massive, emphasizing the vertical development of the form.

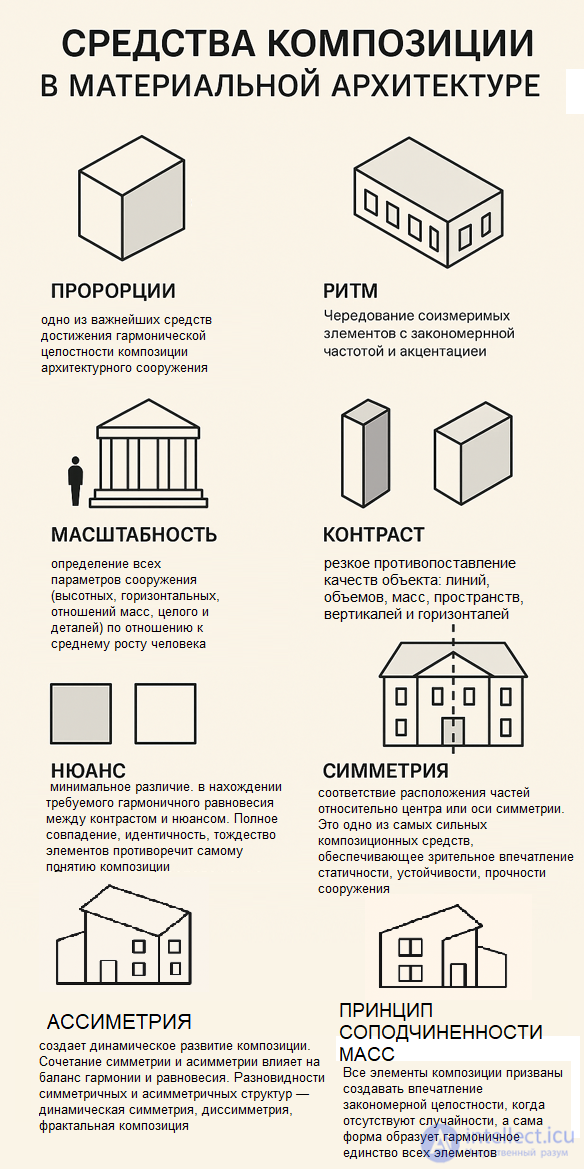

The key tools of architectural composition are proportion, rhythm, contrast, nuance, symmetry and asymmetry. They were described in antiquity by Vitruvius in his treatise "Ten Books on Architecture" - the basic principles remain relevant today.

Proportions play a central role in the formation of a harmonious architectural image. Unlike a simple "ratio", the term "proportion" implies the equality of two or more relationships between quantities. Ideal harmony of proportions is often associated with the "golden section", a concept dating back to Egyptian mathematics (sacred triangle, diagonal grids), perfected by the Pythagoreans and popularized in the Renaissance, in particular by L. Pacioli. Later, methods of graphic construction of proportions were developed, including the "right angle rule" (A. Palladio, Le Corbusier). The proportions of architectural forms are closely related to the human body - its anatomy, movement, psychological perception and ergonomics, which is reflected in engineering design and the training of architects.

Scale is the correlation of all the dimensions of an architectural object (height, width, volumes, details) with human dimensions. It determines how comfortable and understandable the space is for perception.

Rhythm is a regular alternation of elements that are similar in size and shape. Together with meter (uniform sequence), rhythm forms the structural organization of space. These principles are worked out during design, including with the help of digital modeling tools.

Contrast is a technique based on a sharp opposition of characteristics: form, line, mass, directions. It helps to highlight important elements, enhances perception and accentuates semantic centers.

Nuance is a subtle difference between similar elements. The correct use of nuances allows you to achieve expressiveness without excessive harshness. The balance between contrast and nuance gives the composition depth and plasticity. Complete identity of elements, on the contrary, kills expressiveness.

Symmetry is the balance of forms relative to an axis or center. It gives the structure a sense of stability, order, sustainability, and is closely related to the tectonics of architecture.

Asymmetry, on the contrary, brings movement and expressive dynamics. The use of asymmetrical solutions allows creating a lively and emotional space. Their combination - symmetry and asymmetry - can be realized in the form of dissymmetry, dynamic symmetry or fractal composition.

The hierarchy of masses, or the subordination of volumes, is also of great importance. This is the principle by which architectural forms are not organized chaotically, but with a clear distribution of dominants, subordinates, and auxiliary elements. As a result, the composition is perceived as a structurally constructed and integral solution, in which chance is excluded, and each element is in its place.

How does organized space affect perception and gameplay?

Composition is the foundation of artistic architecture in games. It defines how elements of a level, building, and environment come together to create atmosphere, guide the player, enhance the narrative, and support the rhythm of gameplay. In game architecture, composition works on multiple levels: visual, spatial, emotional, and functional.

The architectural composition should create a sense of coherence and logic in the world. Even in fantasy settings, the player intuitively expects that the elements will correspond to real laws: a building has a foundation, supporting structures, proportions; streets connect key points; the interior serves a specific function. Such logic makes the space convincing.

Example: In The Last of Us, destroyed buildings and city blocks follow a recognizable compositional logic - the player knows where the entrance was, how to move, what can be used as cover.

Composition is used to direct the player's attention. Perspective lines, lighting, contrast of shapes and colors - all this directs movement and gaze. Architecture helps not only to navigate, but also to make decisions: where to go, what to explore, where the danger is.

Example: Uncharted often uses broken bridges, arches, stairs, and other architectural elements to "hint" the route through the environment.

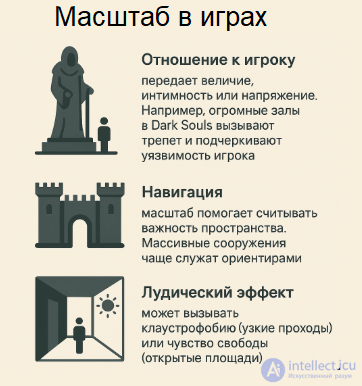

Relationship to the player: Conveys grandeur, intimacy, or tension. For example, the vast halls of Dark Souls evoke awe and emphasize the player's vulnerability.

Navigation: scale helps to read the importance of space. Massive structures often serve as landmarks.

Ludic effect: can cause claustrophobia (narrow passages) or a feeling of freedom (open spaces).

In games, scale is the ratio of the sizes of objects in the game world to each other and to the player character. It plays a key role in shaping the perception of space, gameplay and atmosphere. There is a distinction between physical scale (the sizes of models, levels and distances), visual scale (how objects are perceived visually, even if they do not correspond to real proportions) and gameplay scale (how convenient and understandable it is for the player to navigate and interact with the world). Developers often deliberately distort the scale: they make doors larger than necessary or simplify distances to speed up movement and make the gameplay more dynamic. Scale affects sensations - spacious locations evoke a feeling of freedom, and narrow corridors - tension. In multiplayer shooters, for example, a balance of scale is important so that the maps are not too large (which will slow down the pace) or too small (which will lead to chaos). Thus, the right scale is not just a question of realism, but an important design tool that affects the perception, convenience and emotions of the player.

Spatial dynamics: repetition of elements creates predictability or, on the contrary, by disrupting it – tension.

Pace of progression: Regular changes in architecture can create a rhythm for the player, such as alternating between fighting arenas and corridors.

Musicality of the environment: architecture, like music, can “sound” – set the tone of a location.

The rhythm of events in games is the sequence of events that occur during the game.

Rhythm in games is the dynamics of the change of events, the pace of the gameplay, and the alternation of tense and calm moments that shape the overall emotional perception of the game. It can be expressed in the level of activity, the frequency of encounters with opponents, the change of gameplay situations, the rhythm of the music, and even the construction of levels. A properly constructed rhythm helps to hold the player's attention, creating a balance between action and respite. For example, an intense battle can be followed by a moment of exploration or dialogue, giving the player time to recover. In horror games, the rhythm is often broken by unexpected events to increase anxiety. In platformers and rhythm games, it can literally be built into the mechanics: jumps, attacks, or movements are synchronized with visual and audio cues. Different genres require different rhythms - arcade games tend to have a fast, intense pace, while adventure games may develop more slowly. Rhythm management is a critical tool in drama and game design that developers use to direct player attention, evoke emotion, and make the gaming experience rich and memorable.

Rhythm in games from an architectural point of view is the repetition and alternation of elements of the environment that direct the player's movement, form the visual structure of the space and set the pace of perception of locations. Architectural rhythm can be expressed in symmetry, intervals between columns, openings, lighting, alternation of open and closed spaces. It helps to create a sense of order, logic and direction, which is especially important in navigation through the game world.

Repeating architectural elements (columns, windows, spans) create rhythm—visual and gameplay. They can emphasize movement (long corridors), set the pace (changing rooms), and provide structure to levels.

Example: in Assassin's Creed, the rhythm of the city's architecture aids perception and platforming gameplay - the distance between ledges is calculated for parkour.

For example, in corridor levels, equally spaced arches, windows or niches can set a visual rhythm, by which the player unconsciously "reads" the pace of progress. In urban spaces, rhythm manifests itself in the change of dense buildings and open spaces, which creates a contrast and affects the emotional state of the player. In temples, palaces and other monumental structures, rhythm emphasizes grandeur and scale, and in industrial locations - severity and functionality.

Architectural rhythm can also be used for emphasis: a sharp disruption (such as an irregular element or a broken section of a wall) draws attention and can serve as a landmark or an interactive point. In well-designed games, architectural rhythm is closely linked to the rhythm of gameplay: for example, a series of similar rooms can be followed by a spacious hall with a fight or a cutscene, creating natural peaks and valleys of tension. Thus, architecture in games not only shapes the world, but also actively participates in the construction of rhythm, influencing the speed, direction, and emotional intensity of the gaming experience.

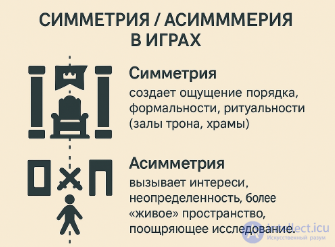

Symmetry: creates a sense of order, formality, ritual (throne halls, temples).

Asymmetry: creates interest, uncertainty, a more “alive” space that encourages exploration.

Symmetry and asymmetry in games from an architectural point of view are key principles of composition that affect the visual perception of space, orientation in the level and the emotional state of the player.

Symmetry in game architecture creates a sense of order, stability, and predictability. Symmetrical buildings, halls, or squares are easy to read visually, helping the player navigate and quickly understand the structure of the space. Such solutions are often used in temples, palaces, military bases, or official buildings to emphasize importance, strength, or monumentality. Symmetry helps create balance and aesthetic harmony, especially in scenes with a high degree of solemnity or in "central" areas, such as boss rooms.

However, too much symmetry can make a space feel boring or too static. So even in symmetrical spaces, designers often add local asymmetries—broken areas, decorative elements, changes in lighting—to create interest and avoid monotony.

Asymmetry, on the contrary, brings liveliness, dynamics and a sense of unpredictability. It is often used in real or pseudo-realistic locations - residential areas, natural areas, industrial facilities. Asymmetrical architecture makes the world more organic and alive, promotes exploration, and arouses interest. In battle arenas or multiplayer maps, asymmetry can be used to create tactical diversity and unique routes, but it requires careful balance so as not to create an unfair advantage.

In some cases, symmetry is applied at the macro level (for example, a city plan), and asymmetry is applied at the micro level (the placement of objects in the interior). This creates a sense of order without losing naturalness.

Thus, symmetry and asymmetry in the architecture of game worlds are not just visual techniques, but tools of storytelling, navigation, emotional impact and gameplay balance. Their competent combination allows you to create expressive, functional and memorable game spaces.

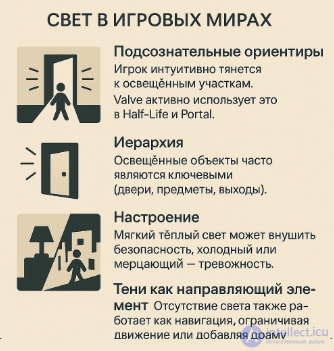

Subconscious landmarks: the player is intuitively drawn to illuminated areas. Valve uses this extensively in Half-Life and Portal.

Hierarchy: illuminated objects are often key (doors, objects, exits).

Mood: Soft, warm light can inspire security, while cool or flickering light can inspire anxiety.

Shadows as a guiding element: The absence of light also works as navigation, limiting movement or adding drama.

Light plays not only an aesthetic role in games, but also a functional one, serving as a powerful navigational tool. Its influence on the player's behavior is often carried out at a subconscious level, guiding, prompting and enhancing the impressions of the gameplay. Let's look at the main aspects of this mechanism.

Subconscious landmarks. Players are intuitively drawn to light. This behavior is deeply rooted in the human psyche: light is associated with safety, progress, and purpose. As a result, illuminated areas of a location often become natural landmarks. Companies like Valve masterfully use this principle - in Half-Life, Portal, and other projects, light gives the player subtle hints, indicating the direction of movement or drawing attention to important elements of the level. Even in the absence of an interface or explicit instructions, the player continues to move in the right direction - thanks to the intuitive perception of light.

Hierarchy of elements. Lighted objects in a level usually have special significance. It could be an exit from a room, a door to interact with, an important object or NPC. This technique creates a hierarchy of attention: the light "tells" the player that something important is here. When used correctly, light helps to avoid disorientation, especially in complex levels with many paths. It directs attention precisely and unobtrusively.

Shaping the mood. Light can not only guide, but also influence the emotional perception of the scene. Soft, warm light creates a feeling of coziness and safety, making the player relax and trust the environment. At the same time, cold lighting or sharp flickering can cause anxiety, anticipation of danger or a feeling of alienation. Thus, the color and character of the lighting become part of the atmosphere and drama of the level.

Shadows as a guiding element. The absence of light is also an important navigational tool. Dark areas of the level limit visibility, create tension, indicate where you shouldn’t go, or, on the contrary, where you should look for risk and reward. A clear difference between light and shadow allows you to control the player’s attention and movement without using walls or artificial barriers. Shadow can isolate, frighten, or, on the contrary, hide secrets and resources.

Together, these principles make light and shadow fully-fledged tools for level design and storytelling. When used correctly, they allow developers to guide the player, reinforce gameplay decisions, and emotionally engage them without words or pop-up prompts.

Emptiness and fullness as expressive means in the game space

Emptiness:

Enhances the drama, like a pause in music.

Emphasizes scale (eg desert landscapes in Journey).

Provides space for imagination and rest for the gaze.

Filling:

Conveys density, chaos, warmth or anxiety (e.g. markets, ruins).

May create barriers, lead or restrict movement.

Used for claustrophobic or intense exposures.

The visual perception of the game world is largely formed through the contrast between empty and filled spaces. This technique works not only at the compositional level, but also deeply affects the emotional state of the player, creates rhythm and directs attention. Let's look at how exactly these opposites work.

Emptiness.

Empty space in a game is a powerful dramatic tool. Like a pause in music, it can heighten the significance of a moment, create anticipation, and create silence before the denouement. Visual emptiness is not "nothing," but a way to emphasize what is truly important. It enhances the impression of loneliness, the unknown, or spiritual quests. Journey is a classic example: huge, empty spaces emphasize scale, isolation, and direct the player's internal focus.

Emptiness also gives the viewer a break. The eye rests, the imagination is activated. Spaces free of detail help create a sense of calm, concentration, and depth, especially when used after busy scenes.

Filled areas, on the contrary, create a feeling of density and richness of the world. They can express chaos, fuss, tension or, on the contrary, coziness and warmth depending on the context. For example, dense city markets, broken ruins or cramped living rooms - each of these images carries a different mood, but they are all saturated with details, interactions and noises. Such

a space actively affects perception: it can create visual barriers, limit the player's movement, form routes and scenarios. In conditions of saturation, it is easy to create a feeling of claustrophobia, threat or even overload, which is often used in horror and exposition scenes. Filled areas make the world "tangible", concrete, alive.

The contrast between emptiness and fullness is one of the key tools of spatial dramaturgy in games. It allows the developer to control the emotional rhythm, enhance plot twists and influence the perception of the world. When used consciously, it makes the visual language of the game expressive, deep and memorable.

Composition in game architecture is not just a matter of aesthetics. It is a tool for managing the player's attention, emotions, and actions. A well-built architectural space can not only decorate a game, but also become a full-fledged narrative and gameplay element.

Comments

To leave a comment

Video game architecture

Terms: Video game architecture