Lecture

A family tree is a graphical representation of the relationships between generations in a family. It shows the relationships between relatives, from ancestors to descendants, as branches of a tree. Each branch represents individual family members and their relationships.

A family tree can include various types of information about family members, such as names, birth and death dates, places of residence, and life events. Family trees help people better understand their family history and origins, as well as trace their ancestral lines and connections.

A family tree plays an important role not only in the study of individual families, but also in sociological analysis, allowing researchers to identify patterns of migration, social change, and cultural traditions passed down from generation to generation.

The history of the 20th century, filled with disasters, caused serious “failures” in the social memory of generations, which is directly related to the continuity of the cultural tradition and the reproduction of the value-normative subsystem of society. For the first time, I clearly realized the effect of the loss of social roots, when several years ago, when telling seventh-graders about sociology, I asked them to list their relatives, and even better, to draw a family tree. First, the children suddenly found out that they did not know their relatives well. Secondly, it turned out that they do not know many words denoting kinship relations. Most often, they did not know (or forget) the patronymic, the dates of the main life events (birthdays, weddings, education, places of birth and place of residence of relatives, especially non-residents), and also where and by whom relatives work, or what they do, and sometimes parents. In most pedigrees, apart from parents, only grandparents — grandmothers, great-grandfathers, and more distant ancestors — were mentioned only in isolated cases. However, each family tree averaged about 50 characters. Of course, behind this figure there is a considerable variation. Suffice it to say that the most “uninhabited” tree included 8 people, located on three levels (the informant himself, his parents and grandparents), but on the “largest” tree on six levels (three above the informant and two below it), there were 215 characters. In the late 80s - early 90s, the problem of genealogical trees was developed quite purposefully with both schoolchildren (students of 10–11 grades) and students.

Over the years, the picture has not changed significantly. However, it was found that someone already had ready-made pedigree trees, at different times compiled by parents, and more often by grandmothers or grandfathers. These cases, as well as the active reaction of Leningraders to our request to send to the Biographical Foundation, descriptions of their life, family chronicles and other materials telling about their personal life experience, partly refuted the hypothesis of total destruction of social roots. It turned out that many people consciously sought to preserve their social roots and history of their ancestors.

Violations of historical memory, the “buildup” and ruptures of social roots in world history (not only in Russia and not only in Soviet times) with a more careful approach turn out to be common. Gaps of this kind were caused by epidemics, periods of slavery (not only under the slave system, but also in the new history), wars, revolutions and other reasons. For a long time, conscious concern for the preservation of the roots was the prerogative of the privileged strata of society, which had a completely rational basis - confirmation (and approval) of the legitimacy of their position.

In many countries, including Russia, the forced migration of the peasantry did not contribute to the preservation of the social roots of the “broad popular masses”. The abolition of serfdom in the 60s of the last century, as history has shown, also did not become a noticeable factor in strengthening historical memory. The events of the first half of the twentieth century — three revolutions in a row, a civil war, several waves of mass political repression, the Second World War — most likely only aggravated the tendency towards historical and social amnesia. The loss and distortion of historical memory, the ruptures of social roots quite fall under the Durkheim definition of social fact [1], and this circumstance requires its theoretical understanding. In addition, during the Soviet period of Russian history, this “social fact” became rampant.

The end of the Soviet period caused an exacerbation of people's interest in their social roots. There is a lot of evidence. This includes the appearance of a large number of books containing extensive biographies, memories of relatives and social events, family chronicles and family stories; the introduction in many general education schools of special lessons in which children are taught to make family trees; creation of historical, genealogical, biographical societies, funds, archives, etc. The interest in their social past, more or less distinct and practicable, the desire of people to realize their place in the world, to restore historical memory, can be said to be widespread. This is also a social fact that deserves theoretical understanding.

One of the explanations of the mass interest of people to their social and historical roots is associated with a sharp change in social orientations, the destruction of the old identity and the painful search for a new one. The compilation of genealogical trees is one of the traditional ways of reconstructing the important elements of social being that help a person’s self-determination.

The concept and method of depicting the family tree was preceded by the Aristotelian idea of the “ladder of beings”. Russian scientist PS Pallas (1766) for the first time proved that the linear-step arrangement of organisms does not reflect the relationship between classes of animals and proposed to depict the system of organic bodies as a genealogical tree [2].

The genealogies of kings, rulers, mythical heroes already existed in antiquity, but they acquired special significance in the Middle Ages in connection with the establishment and execution of class (especially noble) privileges. This caused the emergence of special genealogical reference books (in the form of a genealogical tree or tables), in which all members of the main and lateral branches of the genus, their marriage links, were indicated. Especially many such reference books began to appear from the 15th century. Originating and initially developing as a practical branch of knowledge, serving the purpose of proving antiquity and the nobility of the origin of individual clans, genealogy from about the XYII-XYIII centuries begins to take shape as an auxiliary historical discipline (A. Duchesne, P. Anselm in France, J. Dugdale in England, K. .M. Shpener, J.V. Imhof, I. Gatterer in Germany, etc.) [3].

In Russia, genealogical books appeared in the 40s of the XVI century. They contained the genealogies of princely and boyar surnames, whose representatives occupied the highest positions in the state and military apparatus. The most famous "Sovereign genealogist" (1555-1556 years). In 1682, the Chamber of Pedigrees was created to compile the genealogical books of the entire Russian nobility, which supplemented the “Sovereign genealogist” by creating the Velvet Book. After the editions of the Letters' Letter to the nobility (1785), the nobility assemblies compiled genealogical books in which all information about the nobility of this province was entered. These books were kept up to 1917, and all the information contained in them should have been submitted to the Department of Heralds.

From the middle of the XIX century. The genealogies of the Russian princely and noble families, compiled by individual authors, began to appear. In contrast to the earlier (official) genealogies, which were the record-keeping documents, they represented a kind of scientific research.

Initially, genealogies arose “as a practical branch of knowledge” and served to establish inheritance rights, tenure, privileges, etc. by establishing the degree of kinship between people. In this connection, special (mainly state) institutions were created for the conduct of genealogies.

Thus, genealogy as an activity was generated by social practice, and then both the concept itself and the image method (“tree”) were mastered by biology, paleontology, genetics, selection, medicine, linguistics, anthropology, history and sociology. Only in the middle of the XIX century genealogies came to the attention of social scientists. In other areas of knowledge, the principle of the pedigree tree as a research technique, as a method of knowledge, began to be applied much earlier. It is not surprising that today sociology is forced to borrow methods and techniques of working with such structures from biology, linguistics, history and other sciences.

In recent decades, interest in the analysis of genealogical trees has increased significantly. The literature on this issue has thousands of titles. Only the bibliographic database Sociofile (1998) contains more than 150 journal articles, to some extent relevant to the problem of genealogies, among them absolutely relevant - more than 50%. The most popular topic of genealogical research is social mobility (in almost all aspects of this concept), regardless of the scientific discipline within which the research was conducted. The traditional for genealogical problems of inheritance and property, as well as various aspects of reproductive behavior (fertility, nuptiality, fecundity, etc.) are being actively studied. At the same time, methodological aspects of the analysis of genealogies in sociological science are relatively rarely discussed. The recognized leader in this issue is D. Berto [4, 5].

Interesting results were obtained in the study of the inheritance of biological characters, in particular, hereditary diseases [6, 7, 8, 9]. Special attention of researchers is caused by small demographic isolates, in which marriages are between individuals of close kinship. An exceptionally non-trivial view of the problem is the work of P.Sh. Gabdrakhmanova, devoted to the study of the daily life of medieval peasants on the material of family trees (Flanders, XII century). P.Sh. Gabdrakhmanov notes that the history of the private life of medieval peasants has not yet been written. “But can it be written in principle? What are the opportunities for this we have? Most often, we are not able to find out about the peasants anything except the name from documents. But even the name itself is capable of telling a lot, .. - writes P. Sh. Gabdrakhmanov, - in the names of the children their parents ’sociocultural ideas about themselves and their family, about ideals and moral values, about the hopes and thoughts of their children’s fate were manifested . These circumstances allow the researcher, using the methods of anthroponymic analysis, to enter into a “dialogue” with medieval peasants. Moreover, this “dialogue” can be especially productive if the researcher comes into contact not with isolated individuals, but with family-related groups of peasants (italics is ours - O. B.), within which the process of creative work took place. In the case of Laniardis (the name of the ancestor of a peasant family. - OB), it is even a matter of genealogy. Against the background of the relative stinginess of the data of our sources about the private life of medieval peasants, the uniqueness and significance of such documents appears especially clearly ... ”[10, p. 209-238, 212].

More than thirty years ago, K. Bell studied, on the basis of pedigree trees, social and geographical mobility, closeness and nature of social contacts between families belonging to one family-related group, the process of separating young people into independent households, etc. Bell used family trees as a kind of prism through which he viewed family ceremonies and rituals [11].

Our experiments with pedigree trees have shown that even careful looking at (not analyzing, looking at) genealogical trees raises serious research questions. Is social memory really so short, and so fragile are the social roots that they break already in the second - parental - generation? What happens to an ordinary family, why even about their parents, children (already quite adults, not only schoolchildren, but also students) have minimal information? Do parents in such a way try to protect their children from the boring everyday life of the family, or is the family history so insignificant for them that there’s nothing to say about it? Or is this a consequence of alienation between parents and children? If so, what caused this alienation? Or maybe this is another problem in general, which has nothing to do with social roots or historical memory: the problem of work and life in a socialist society? If social roots are really destroyed, if there is deep alienation between children and parents, then the predisposition of young people to neuroses becomes clearer, their helplessness, on the one hand, and cruelty and individualism on the other. They have no one to rely on, they have no “rear”, from all sides there is a front, an incomprehensible and hostile world. Or maybe the secrecy of parents is related to the fact that in relation to their older generations (grandmothers, grandfathers of today's children), the parents themselves have degraded, sank to lower levels of the social hierarchy and are embarrassed about it?

Another possible explanation for the breakdown of social roots is a consequence of the perception of the danger of kinship (especially blood) ties in a totalitarian state that resolved the issue of eliminating “as classes” of a number of estates, which is why people had to hide their social origin. Under these conditions, not only the offspring of “purebred nobles”, aristocrats or priests, but also peasants, merchants, engineers, and officials, blood kinship ties proved extremely dangerous. And then family ties became dangerous for the children of the party members, revolutionaries and civil servants of the “first wave” and, finally, in general for everyone whose family got under the rink of repression. In the 70s, the myth of the “new social community - the Soviet people” was created. An analysis of a large array of genealogies could contribute to an understanding of what was the technology of “melting down” ordinary people into a “new social community”?

“Trees” are not difficult to find in software products that are used today in any personal computer. Take, for example, Windows-95. What is an explorer is a non-hierarchical tree. The tree principle is also used in blocks like “Data Model Design”, “Paradox for Windows” and other programs. In 1997, the advertising campaign of the new version of the program “QSR NUD * IST 4” brought to the first lines of advertising leaflets, pamphlets, booklets a message about the addition of this package with tools for constructing a bierarchical tree.

Examples of active use in programming of the “principles and methods” of hierarchical (genealogical) trees are innumerable. It is enough to say that pedigrees or family trees are just one of the types of tree structures considered by graph theory, along with hierarchical structures, Petri nets, etc.

In recent years, quite a few specialized software products have been created that are divided into at least three groups: 1) tools for building family trees and organizing a specific database; 2) tools to support a specific format (PAF, GEDCOM) corresponding to the standard; 3) tools for graphical representation and design of genealogies (family albums, for example), as well as their recording on CDs or design of web pages. The absence of any programs designed to analyze either individual genealogical trees or data arrays of this kind is noteworthy. The publications present the results of processing the genealogical data, but it does not mention with the help of which analytical apparatus, with the help of what computer technologies they obtained.

Available software products, for example, Corel Family Tree Suite, Family Tree Maker, have undoubted advantages, first of all it refers to the refined service. However, they all offer a rigid database structure, and it is unclear whether it is possible to edit and modify it. Trees are stored in separate files (or subdirectories), and until the means are found that would allow to “collect” and analyze the set (array) of trees. In these packages, there is no apparatus for analyzing even a single tree (elementary statistics, that is, information on the number of persons and families displayed in the tree can be disregarded). But for the time being it was not possible to display the entire tree on the screen or on the printer (however, it is quite possible that this is merely a fact of our personal biography).

The main difficulty lies in the fact that sociological information is still required to be extracted from genealogical and family trees, to dissect in a certain way, to make it obvious and “transparent”. The data obtained by traditional sociology polling methods are of little use in this regard.

First, survey methods (questionnaires, interview plans) are not only focused on individual informants, but also problematize their own behavior, individual motives, assessments, attitudes, value orientations. This is clearly seen in attempts to describe the family structure in questionnaire surveys (Table 1). In this case, inconveniences arise with the numbering of signs, coding, etc. Family members are determined in these cases exclusively in relation to the respondent, which complicates the accurate and theoretically meaningful description and analysis of the actual structure of families and family-kinship relations. As a rule, it comes down to flat typological structures like the following: “1 - singles; 2 - only spouses without children; 3 - spouses with children; 4 - spouses without children with parents; 5 - spouses with children and parents (grandparents); 6 - one of the spouses with children; 7 - one of the spouses with children and with parents (grandparents); 8 is another. ” A definite way out of this difficult situation was found by Moscow colleagues, who presented family-family relations in a structural form and described them without being locked in on the respondent (Table 2) [14]. Probably, the objectives of the study did not require a more detailed fixation and description of kinship relations than is given by the coding scheme. However, it is possible that the analyst’s “freedom” is also limited by the specifics of the questionnaire method.

Secondly, the feature space of traditional empirical data, as a rule, is either a very “rigid” scheme intended for statistical testing of local, private hypotheses, or, on the contrary, is oriented towards a lengthy description and, as a result, is very eclectic, touching upon many topics, each of which is revealed very superficially. Thirdly, family and kinship relations in different sciences are described in different “languages”. Sometimes we use words (for example, “degree of kinship”), without realizing that they have a certain “registration” (in this case, demographic) and a fairly specific meaning that does not coincide with that which an empirical sociologist puts into them. In particular, in demography, degrees of kinship are reflected by the concepts of “native”, “cousin”, “second cousin”, “uncle”, “aunt”, “nephew”, “grandson”, and “mother”, “father”, “brother”, “sister”, etc. have no relation to the degree of kinship. In linguistics, biology, and other sciences, this same concept is filled with a slightly different content and is reflected in other concepts.

Fourth, traditional survey methods are definitely focused on the present (extremely rarely on the past, and then, as a rule, very close - 2-3 years, at least 5 years), and on living people, whereas the pedigrees are “inhabited” not only alive, contemporaries and descendants, but also ancestors, both close and very distant.

Table 1 An example of the presentation of a block of questions about family composition in sociological questionnaires. Describe all family members registered in this area (start with yourself):

|

Relation degree |

Age |

Education |

Place of Birth |

Occupation |

|

| 4-8 | |||||

| 9-13 | |||||

| 14-18 | |||||

| 19-23 | |||||

| 24-28 | |||||

| 29-33 |

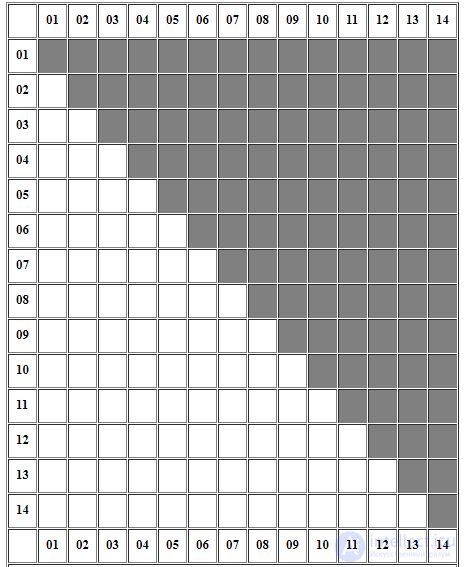

table 2

Relationship Matrix

| Coding scheme | |||||||||||||||

| 01 - husband / wife | 08 - Grandpa / Grandma | ||||||||||||||

| 02 - father / mother | 09 - grandson / granddaughter | ||||||||||||||

| 03 - stepfather / stepmother | 10 - nephew / niece | ||||||||||||||

| 04 - son / daughter | 11 - father-in-law / mother-in-law, father-in-law / mother-in-law | ||||||||||||||

| 05 - step son / step daughter | 12 - son-in-law / daughter in law | ||||||||||||||

| 06 - brother / sister | 13 - other relatives | ||||||||||||||

| 07 - stepbrother / half-sister | 14 - other persons, not relatives | ||||||||||||||

The so-called qualitative data stand apart, in particular, biographical interviews, the materials of which are, as a rule, lengthy interpretations of phonograms. Nevertheless, the range of questions addressed to the respondents even in specialized biographical interviews usually fits into a rigid scheme, formed on the basis of ideas about the limited space of spheres of life: family, study (education), work or work, life, leisure, personal self-realization (hobbies, hobbies, etc.). In recent years, this circumstance has become recognized as a certain methodological problem, and is being intensively discussed within the framework of the research committee “Biography and Society” of the International Sociological Association [15, 16, 17, 18, 19].The thematic assignment of biographical interviews and autobiographies is aggravated by the translation of oral speech into written texts, when the researcher “smoothes” and “combs” the author's text, leading it to the norms of the literary language, and in essence performing the primary interpretation in such a way, inadvertently but very significantly distorts the outlined respondent facts. Sociological conclusions based on “free” texts seem somewhat arbitrary. This is, rather, the researcher’s fantasies “based on” the interview, rather than the results of their rigorous scientific analysis. And finally, if genealogies are cited in sociological publications, it is mainly as illustrative material. There were no exceptions and the materials of the international seminar in Slovakia (August 17-23, 1992),dedicated to the sociological understanding of life stories and family genealogies. Although today more often than 30 years ago, you can find characteristic graphs describing family-related groups, family trees are a relatively new type of object for a sociologist.

Let us consider genealogical trees in a series of other methods of sociological research: standardized questionnaire survey, focused interview, biographical interview. In this case, it is necessary to take into account the following aspects or attributes: the status and functions of the person from whom specific information comes; the nature of the information received; methods of organizing and presenting information; methods of processing and analyzing the received data (Table 3).

Strictly speaking, only a standardized questionnaire survey belongs to the class of formalized, quantitative methods; other types of surveys are most often classified as qualitative today. There are two subtypes of biographical interview. One - thematized by the researcher - is practically no different from the focused interview, at least in that in the pair "respondent - interviewer" in both cases the interviewer is the leader. The second is a fundamentally different type of method, in which the initiative is purposefully given to the respondent. Therefore, it is correct to call the latter not a respondent, but a narrator or informant.

We draw attention to the differences in the motives of participation in the study of all the above subjects. The motivation of the respondent fits into the framework of traditional patterns of cultural behavior. It can be strengthened or weakened by the presence (or absence) of the respondent's personal interest in the problem to which a particular study is devoted; interviewer's skill (or lack thereof). However, in most cases, the respondent behaves according to the patterns of a “polite” or “law-abiding” person. A different nature of motivation is observed in an unmatched biographical interview. Here the “autobiographical impulse” [21] of the narrator begins to work, forming a rather complex motivational complex and “including” additional incentives. Many researchers note that the biographical impulse has a significant “energy field”,which creates very serious psychological and socio-psychological problems and gives rise to the specific task of developing special socio-psychological defense mechanisms for the researcher and / or interviewer.

With genealogical trees everything is different. Regardless of whether the compiler of the genealogical tree undertakes a case on his own initiative or on the initiative of the researcher, he begins by referring to his own memory, then proceeds to an “external” search and analysis of documents and sooner or later comes to different types of survey (even polls his parents, grandparents or other relatives). At the same time, he voluntarily assumes the functions of a researcher. Finally, unlike other cases mentioned above, here the informant (not the respondent and not the narrator!) Collects information mainly about other people, and not about himself. In the genealogical tree, the author himself “dissolves”, “mixes” with the family-related group - this is just one of the leaves of the tree. “Genealogical impulse” as a motive is much stronger than biographical and has a different nature. If the biographical impulse is “looking for a way out” and is certainly oriented towards the reader or listener, then the genealogical one has a deeper personal basis and, most likely, does not need external stimuli to that extent.

Table 3 Comparison of various methods of collecting primary sociological information

| Method of collecting primary information | The status and functions of the person from whom comes | Nature of information | Ways to organize and present information | Methods for processing and analyzing data | ||

| information | at the collection stage | at the processing stage | ||||

| Standardized Questionnaire | Respondent | Monologue of the respondent formalized by the researcher | Text document, form | Matrix of numeric data | Algorithms for Standard Statistical Analysis | |

| Focused interview | Respondent | Dialogue with the respondent formalized by the researcher | Text document, form | Text, hypertext or matrix of numeric data, less database | Qualitative description of the data. Post-coding algorithms for standard statistical analysis | |

| Biographical interview (themed by sociologist) | Narrator, (respondent) | Narrator's narrator narration about his life | Text document, form, script | Text document, narrative | Qualitative description of the data. In the case of data coding, statistical analysis algorithms | |

| Biographical interview (themed by the informant) | Narrator | A narrator about his life built by the narrator | Absent | Text document, narrative | Qualitative description of the data. Classification. Coding. Typologization. Structural models. Simple statistics. | |

| Family tree | The organizer of the collection of information | Institutionalized information about other people (relatives and relatives) | Absent | 1) Relationship graph; 2) its description (text) | Qualitative description of the data. Typologization. Structural models. Simple statistics. | |

Thus, as one moves from a standardized questionnaire to a pedigree tree (Table 3), the status and functions of individuals who are the “suppliers” of primary sociological information gradually change. At the same time, the nature of the information itself changes, both in content and in form. Firstly, the reported information is gradually “released” from the influence of the researcher, and secondly, it becomes less and less “closed” on the respondent and covers a wider range of social actors.

The changes also affect the presentation of information at both the collection stage and the data processing stage. At the information gathering stage, a document or form gradually loses its “rigidity”, “predestination” as it moves from one method to another, leaves more and more space for personal, individual features of an informant, not a researcher, and finally, is completely freed from the original (and actively imposed) conceptual models of the researcher.

It seems appropriate to touch upon the problem of quantitative and qualitative methods. First, different authors put meaning in these concepts a different meaning, and secondly, with all the variety of meanings of the word “qualitative,” most often qualitative information is called information that is more difficult to formalize. Indeed, it is considered that a standardized questionnaire with its closed questions is understood by all participants in the study (researchers, interviewers, respondents and even customers) unequivocally. It is precisely because of its high formalization that the data obtained is usually presented in the form of a matrix (rows - respondents, columns - attributes). With careful theoretical elaboration, the materials of a focused interview, originally presented in the form of a tape or handwritten recording, can also be converted into a numerical matrix after encoding. In relation to biographical interviews, a stable prejudice has developed that this “delicate matter” does not lend itself to formalization and, therefore, coding.

From the point of view of the possibilities of formalization, the epithet “qualitative” does not fit the pedigree tree, for genealogies themselves are well enough structured and completely formalized. Another thing is that it is not very easy to apply the algorithms of statistical analysis traditional for sociology to this structure, but this is a separate issue, which we will not discuss in this article.

We note only that if in the graph table. 3 “The nature of information” is the general trend (as it moves from top to bottom) - an increase in the “respondent’s” freedom, then in the “Methods of data processing and analysis” column, the general trend is an increase in the freedom (or arbitrariness) of the researcher; or (as a practical alternative) the deepening of theoretical analysis and methodological reflection. All these circumstances are essential not only for the characteristics of each method, but also for assessing the status and quality of the information collected, its meaningful and reliable interpretation. As you can see, the choice of method has important consequences and determines the type of research (or is determined by the type of research itself).

The method of the family tree differs significantly from other methods (objects) of sociological analysis in the form of organization and presentation of information. It has a “complex” character and consists of two parts. The first is a drawing or a graph, where each character is a “peak”, and the connections of one peak with others are “edges”.

Ribs denote different types of communication: vertical edges usually indicate blood relations between generations, and horizontal ones - related and intrinsic relations within one generation). The second part is a description of the vertices and edges of the graph, either in the form of relatively free text or in the form of a table.

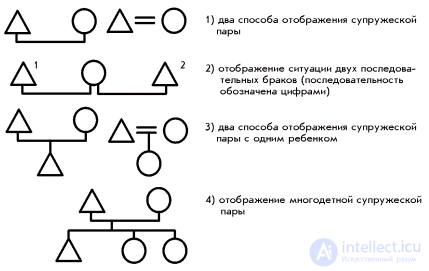

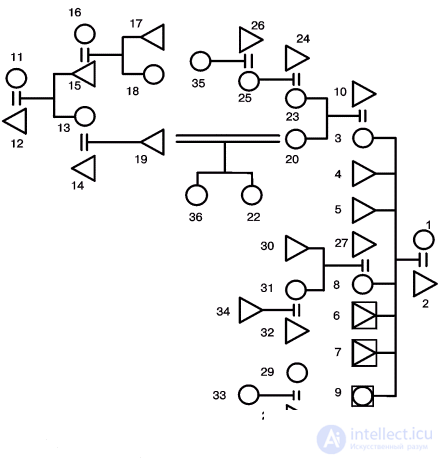

Fig. 1. Typical pedigree tree figures (basic elements)

Consider some typical (elementary) figures of genealogical trees (Fig. 1). In itself, the tree forms a framework defined by a clear structure of related and intrinsic bonds (Table 4). Some of the relationships can be qualified as direct : parents – children (including the relationship “father-in-law – mother-in-law” and “father-in-law — daughter-in-law, daughter-in-law”) are spouses. Other links are mediated. First, it is an uncle / aunt, grandmother / grandfather, great-grandmother / great-grandfather, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, nephews, etc .; secondly, sister-in-law, maiden land, brother-in-law, yatrov, sister-in-law, etc. (the latter are sometimes called not related but “intrinsic” relations). However, regardless of the type of these links, the graphical path between any two characters of the family tree has a clear description and can be calculated.

Table 4 Basic Russian Kinship Terms

| Female line | Male line | ||

|

Title |

Value |

Title |

Value |

| Mother | The first woman on the pedigree, from which came the race, generation, house, knee | Forefather | The first man on the pedigree, from whom came the race, generation, house, knee |

| Great-grandmother | Mother grandparents | Great grandfather | Grandparents father |

| Grandmother | Mother of father or mother | Grandfather | Father father or mother |

| Mom mother | Parent | Father | Parent |

| Stepmother | Father's other wife in relation to his children | Stepfather | Mother's other husband in relation to her children |

| Daughter | Every woman's father and mother | A son | Every male child father and mother |

| Stepdaughter | Daughter from the first marriage to another husband of the mother | Stepson | Son from first marriage to another wife of father |

| Sister11 | Daughter of some parents to those whom she is a sister | Brother | Son of the same parents to those to whom he is a brother |

| Cousin | Daughter uncle or aunt | Cousin | Son of uncle or aunt |

| Wife | Spouse | Husband | Spouse, master, forming a couple with his wife |

| Granddaughter | Daughter son or daughter | Grandson | Son of a son or daughter |

| Great granddaughter | Daughter of a grandson or granddaughter | Great-grandson | The son of a grandson or granddaughter |

| Aunt | Father or mother sister | Uncle | Brother of father or mother |

| Niece | Daughter of brother or sister | Nephew | Son of brother or sister |

| Nipple | Husband's sister, also brother's wife | Devery | Brother husband |

| The bride | Son's wife, husband's wife | Son-in-law | Husband's daughter, husband's sister, husband of sister-in-law |

| Daughter in law | Son's wife | Son-in-law | Husband's daughter, husband's sister, husband of sister-in-law |

| Mother in law | Mother of husband, wife-in-law | Father-in-law | Husband's father |

| Mother-in-law | Wife's mother | Father-in-law | Wife's father |

| Mother-in-law | Wife's sister | Brother in law | Wife's brother |

| Yatrov | Brother-in-law's wife, wife of deuce, wife of brothers among themselves | Svoyak | The husband of the sister, as well as the husbands of the sisters among themselves |

| Mother-in-law | Wife's sister, the same as yatrov | ||

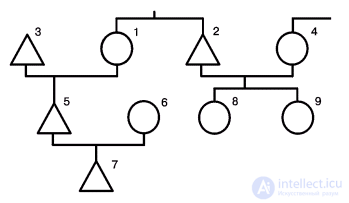

We give a description of the relationship between the characters presented in Fig. 2. Characters number 1 and number 2 brother and sister. Each of them has its own family: No. 3 is the sister's husband (No. 1), that is, relative to No. 2 is a brother-in-law, and No. 4 is the brother's wife (No. 2), that is, in relation to No. 1 sister-in-law. Thus, we have described the relationship of the property between the characters of the top level of the tree. Let us proceed to the next level: No. 5 - son No. 1 and No. 3, No. 6 — his wife, that is, his mother's daughter-in-law (No. 1) and his father’s daughter-in-law (No. 3). In relation to No. 5, characters No. 8 and No. 9 are cousins, that is, the daughters of his uncle (No. 2).

Fig. 2. Fragment of conditional family tree

Even if the author-compiler of such a lineage indicated only characters No. 8 and No. 9, designating them as cousins of character No. 5, and not specifying characters No. 2 and No. 4, we would have good reasons to “reserve” a place on the tree for a brother or sisters of one of the parents (№ 1 or № 3) of this character. It is in this sense that we speak of the “computability” of the path between any two characters of the family tree, even with some of its incompleteness.

A family tree is not just a collection (or network) of characters united by a system of kinship ties. In its structure, in addition to characters, it is possible (and expediently) to isolate other relatively independent objects. On the one (formal) side - generational levels (in our example in Fig. 2, there are four of them); on the other (substantial) side, “nuclear” families (five in Fig. 2); childbirth or surnames, which in our example are three; family-related groups, households (for the assessment of the two last formations in this example there is no necessary information) and maybe some others.

By the nuclear family, we mean “a small social group consisting of spouses and their children” [23]. A nuclear family can be complete if both spouses and at least one child are available, and incomplete if either one of the spouses or children are missing. Obviously, each character can simultaneously or sequentially belong to different nuclear families.

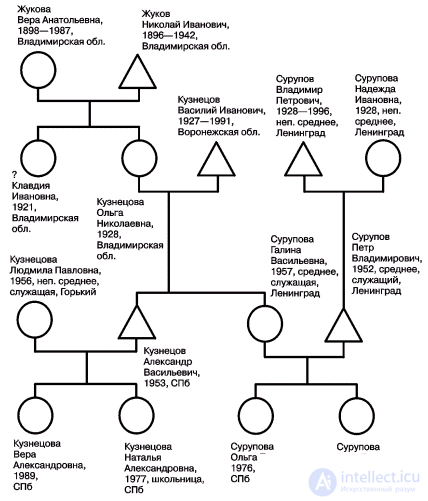

Fig. 3. The family tree of OP Surupova, 1992/1993 school year

By the genus (or surname) we will call all the characters united only by direct (vertical) and indirect (horizontal) blood kinship and having the same surname. Thus, a genus may occupy the entire “vertical” of the family tree, in contrast to the nuclear family, which is located on one or two immediately adjacent generations.

Special discussion requires such an element of the family tree as the family clan . Formally, all the characters included in the family tree constitute a family-related group - the family clan. In other words, a family tree is one of the ways to visualize a family clan. It is advisable to introduce along with the above broad meaning also the specific (narrow) meaning of this concept, implying not the entire set of characters, but only those who are associated with a particular nuclear family with close physical and / or spiritual contacts.

In this sense, the concept of “family clan,” and the family-related group denoted by it, are significantly different from the other generally accepted concept of “ household ”. The latter means persons living under one roof and / or leading a common household. The “family clan” in the narrow sense used here unites not all members of the family-related group, but only those whom the compiler of the genealogy considers psychologically, ideologically, and spiritually close to themselves.

Let us explain this with an example. When schoolchildren began to draw their family trees, they sought to identify and submit to them the maximum number of relatives. At the same time, many experienced psychological discomfort from the fact that a certain (for some people quite significant) part of the characters on their trees is presented purely formally. Yes, these are relatives, but neither in spirit nor “in life” they have anything to do with their family. Some shared their concerns with the teacher. Then the initial task was supplemented with a request to designate on the family tree different colors of those about whom they know little or nothing; whom the informant had never seen personally, but about whom he had heard a lot, with whom he is well known in absentia (family legends); with whom he had communicated ever, at least once; finally, those with whom he and his family communicate constantly or often enough and regularly.

This additional task turned out to be easily accomplished and removed the psychological discomfort; moreover, it provided a clear idea of the degree of cohesion of family-related groups. It became obvious that the concept of “our (or my) family”, in addition to the formal (legal), also has an informal, emotional-psychological content, which, as it seems to us, is reflected in the proposed narrow sense of the concept of “ family clan ” .

The way and nature of the description of family trees or, if you will, the theoretical concept define a lot. In particular, the ideology of the above Corel Family Tree software covers far from all of the elements of the genealogical trees that we have listed. The concept adopted by its authors does not seem to imply a generalized description at all, just as it does not imply the typology of trees and much more, which is interesting and necessary for a sociologist. It is not by chance that the program operates with the terms “individual”, “mother” and “father”, “spouse” as characteristics of an individual, “children” - sablings (as a characteristic of children).

The concept of “events” is also actively used in the program. The range of events is extensive: birth, baptism, confirmation, census, adoption, emigration, graduation, marriage registration, resignation, testament, death and, finally, funeral, that is, almost all important life events with a pious Catholic. At the same time, it is possible to record the place where each event occurred. The proposed range of relationships to individuals included in the tree is wide: “estranged”, separate, independent (separated), confidential, divorced, partner, friend, spouse. “Status of father” includes such definitions as a natural (natural), family member, adoptive parent, official guardian, educator, godson, however, a secret, confidential (private) ioao is also provided. Already from these incomplete data, which CFT authors propose to the user of their product, one can reconstruct the image of the theoretical concept adopted by them and characterize its orientation as very pragmatic and far from the tasks relevant to the sociologist.

First, as a key characteristic, it is advisable to single out the number of tree levels (with separate consideration of “higher” and “lower” in relation to the level at which the originator is located).

Secondly, the total number of characters displayed on it. These are the most common parameters for distinguishing and grouping (classifying, typing) genealogies.

Thirdly, the number of genera (surnames) present on the genealogical tree should be considered as common parameters.

A sufficiently significant characteristic can be the number of the level at which the informant (or respondent) is located. The level number can also be attributed to the general characteristics of the tree. In order for the latter characteristic to acquire the status of a general, a certain standardization is required in the tree description. Indeed, in the minimally and maximally “populated” trees from our collection (Fig. 1, 2) in the first case, the respondent (the compiler of the tree) is on the third level (if you count from the top down) and on the first (if you count on the bottom), in the second случае респондент находится на четвертом уровне (если считать сверху) и на третьем (если считать снизу).Therefore it is worth agreeing at least on the direction of numbering levels. It is also advisable to take as a standard a tree that includes the maximum number of levels, and to “tie” specific family trees to this standard.

It is obvious that the number of the level on which the composer of the tree is located correlates closely enough with the age of the author. However, this relationship is not so tough to replace this parameter with age. In the examples we are considering, both authors are the same age, students of the same class, belong to the same generation, but one of them has a niece who “fills” the “lowest” level of the tree. Binding of both trees to the conditional standard, on the one hand, aligns the “genealogical status” of the respondents - both of them will be at the third (bottom) level, and on the other hand, further emphasizes the fundamental difference between these trees.

Some researchers, in particular, K. Bell, use the method of displaying the genealogical trees, in which the paternal and maternal related groups are initially divorced [11]. In some respects it is advisable and even convenient. At least this form makes it easy to detect a known imbalance in awareness of relatives from the maternal and paternal sides (Fig. 4). However, the overall “depth” (number of levels or generations) of genealogy is not so obvious.

In all likelihood, the range of general characteristics of the tree can be supplemented. We considered a rather large number of possible characteristics, but not all of them seemed invariant (that is, not to a particular thematic class of problems). So, as a general characteristic, one could use any parameter of the respondent himself: age, occupation, place of birth, level of education. But each of them, being in the list of general characteristics of the tree as a whole, more or less rigidly tematizes (links to a specific thematic area) the entire collection.

The next key element of the family tree is the generational level (or knee), in our opinion, deserves a separate description, since it characterizes the structure as a whole. It is advisable to single out the following its thematically independent (invariant) indicators: the total number of characters that make up this level; total number of couples; the number of unmarried characters; the number of characters in more than one marriage; the number of children, that is, the number of “exits” to a lower level of genealogy or “edges of the graph”, connecting this level with the more “younger” (or with the level of immediate descendants); the ratio of the total number of characters that make up this level to the number of all children born by its “representatives”. It is easy to see that all the indicators listed are purely quantitative.It is this fact that gives them the status of general characteristics of any level of genealogy, invariant with respect to a specific topic.

Comparison of descriptions of different levels (tribes) presented in a given genealogical tree is a fairly powerful tool for typologizing the trees themselves. In particular, one of the possible results here may be, for example, a three-member typology of genealogical trees or family clans (in the broad sense) of the following type: 1) growing, developing; 2) stable (self-reproducing); 3) fading, disappearing.

Fig. 4. Genealogical tree of M.O. Zheltoukhova (St. Petersburg State Academic Certification Committee, 1992/1993 academic year)

Description of individual objects (substructures) of the genealogical tree

Let us consider the main elements of the genealogical tree (relatively independent objects on it), listing with minimal comments the characteristics (indicators) necessary to describe each of them.

Nuclear family. Date of family formation (date of marriage of spouses or date of separation of an adult single person from the parent family); date of family breakdown (death, divorce, or some other reason); The “age” of the family or the duration of the marriage; number of children; total number of family members; dates of separation of children from the parent family.

Gender (surname). The number of characters that make up the gender; the number of nuclear families that make up the genus; the number of levels at which members of the genus are located; range (numbers) of genus levels; the number of married women retaining their maiden (generic) surname.

Comment . As already mentioned, in recent years, due to a number of political, economic, national and other reasons, people's interest in their origins, in the history of their last name, of their own kind has increased. In Russia, it is precisely what is happening, as it seems to us, significant (in some ways irreversible) changes in this area.

When studying each of the elements (objects) of the family tree we have identified, a certain range of tasks and problems arises. In particular, in modern studies in the field of medical genetics, it was not by chance that we used what we called a genus as an object of genealogical analysis, since genetic problems are inherent in this particular object.

Family clan (in the narrow sense). The total number of characters attributed to this clan; the number of nuclear families in the clan; the number of generational levels covered by the clan; range of levels (their numbers); the number of births (surnames) assigned to the clan; the dominant type of relationship in the clan.

Comment. The description of this object is associated with certain difficulties, since there is no certainty that the listed characteristics are necessary and sufficient. Clear and transparent identification of family clans is also not an easy task and will require additional serious work. There is no doubt about the significance of the selection of this object, as well as that the study of family clans will be useful and interesting from many points of view.

The household. “Household” is defined as a family-related group living “under one roof” and running a common household. Identifying this section of the family-related structure requires some special efforts, at least an additional setting for the compiler of the genealogy and the introduction of additional features. The household is distinguished by a greater thematic commitment compared to other elements of the family tree and hides “pitfalls”. In particular, household members are not necessarily relatives and not exclusively relatives, but almost always these are people whose relations are formalized legally (which is very often unimportant for actual family ties). Nevertheless, we included this element in the description, believing that it will play a significant role in social processes. The following seems essential for describing the household: the name (or number) of the household, the number of persons included in the household; the proportion of women (or men); the number of surnames (clans) represented in the household; the number of nuclear families.

A specific character (individual). Gender, dates of life (birth and death); number of marriages; date of each marriage; date of termination of each marriage; place of birth.

Comment. The number of characteristics of individuals may be greater, but we limited ourselves to only those named above, since other parameters are quite strictly defined by a specific research topic (occupation, profession, education, qualifications, place of residence, place of work). However, both the date of marriage and the date of termination of marriage can be qualified as thematically biased.

The position “place of birth” may seem controversial, since the place of birth of a person is in a certain sense random. There are many known cases when women give birth, for example, on the road, and subsequently the person never manages to get to the place where he was born. However, the rule is different: the place of birth is quite closely connected with the long-term residence of either the person himself or his parents.

The “dates of life” position (as well as “dates of marriage”) can have two states: closed, if the character is dead (or if the marriage has broken up), and open, if the character is alive at the time the tree is compiled (and the marriage is valid).

People who try to build their family trees often feel that it is useless to seek help from any institutions, although in recent years quite a few organizations have appeared that deal with genealogy issues. Societies and unions that unite the descendants of the nobility

продолжение следует...

Часть 1 Genealogical (genealogical) trees as an object of sociological analysis

Часть 2 “Human” features of the method - Genealogical (genealogical) trees as

Comments

To leave a comment

Sociology

Terms: Sociology