Lecture

Since the Stone Age, people have used various tools to expand their capabilities and adapt to changing needs. In the past, only a few managed to perfectly master some kind of creative skill, but with the advent of assistive systems, creativity became more accessible. In this section, we will look at three generations of support systems for creativity and analyze how they contributed to the democratization and escalation of creativity.

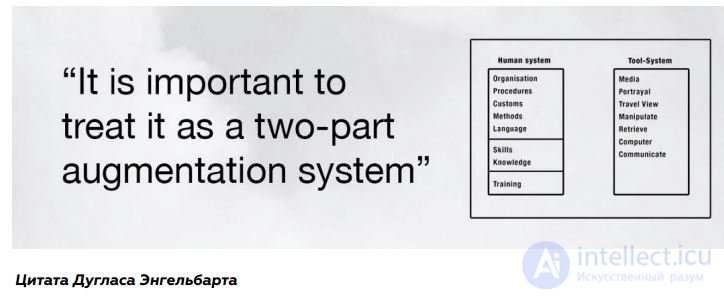

Influenced by Engelbart’s ideas, many scientists began to explore how computer systems can “assist” a person in performing creative tasks. Researcher Ben Schneiderman described such systems as “technologies that help more people perform more creative tasks for a longer time” [1]. In the context of this research, companies such as Apple and Lotus developed the first digital products for creative tasks. In addition, new companies have appeared: for example, Autodesk (1979) [2] and Adobe (1982) [3], which fully specialized in the development of tools and systems for creativity.

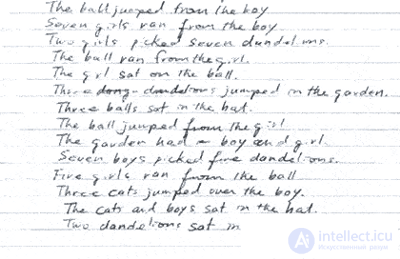

In the 1980s, the development of the first systems of assisted creativity appeared in the industry: Photoshop, Autocad, Pro-Tools, Word and many others. The first generation of such systems simply imitated the capabilities of analog tools using digital technologies [4]. The implementation of creativity required the full attention of a person: the feedback was slow, and the capabilities of the “assistant” were extremely limited. Nevertheless, such tools enhanced the creative abilities of experts and beginners, which led to a wave of new creative processes and results.

The autofocus of the camera, invented by Leica in 1976 [5], can be considered an early example of the systems of the second generation of assisted creativity. In these systems, creative process management takes place through constant feedback. The machine can significantly affect the result, so the process is managed together. Decisions are made by man and the system together. Such second generation systems are ubiquitous in the modern world. They are widely used in all countries and industries. Autocorrection, which in 1991 was invented by Din Hakamovich of Microsoft, influenced the written speech of millions of people, and the automatic adjustment of sound (Autotune) changed the process of creating music.

It is difficult to assess the effect that these systems have had on different spheres of creativity, only one thing is clear: systems of assisted creativity reduce the input barrier of owning a creative tool. This allows participants in the creative process (both professionals and amateurs) to concentrate on higher-level issues, perform complex creative tasks and carry out various kinds of experiments more quickly. And although the use of such systems is associated with certain risks and difficulties, in most cases they do increase our creative abilities.

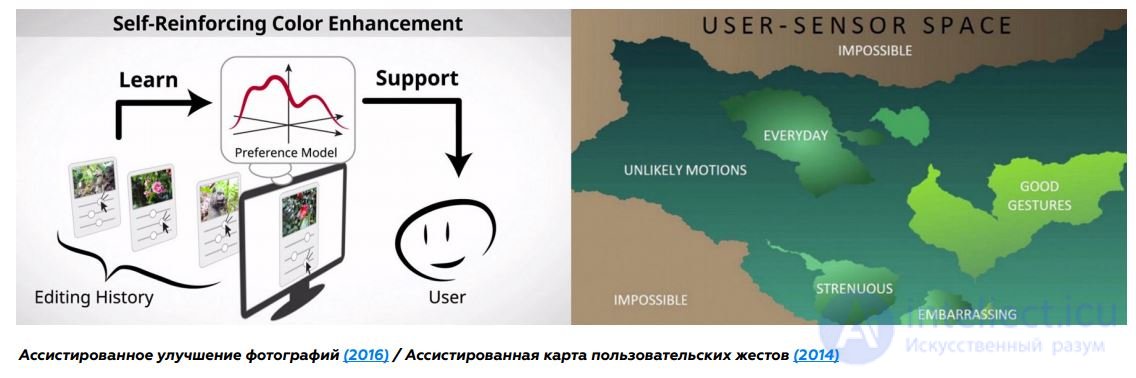

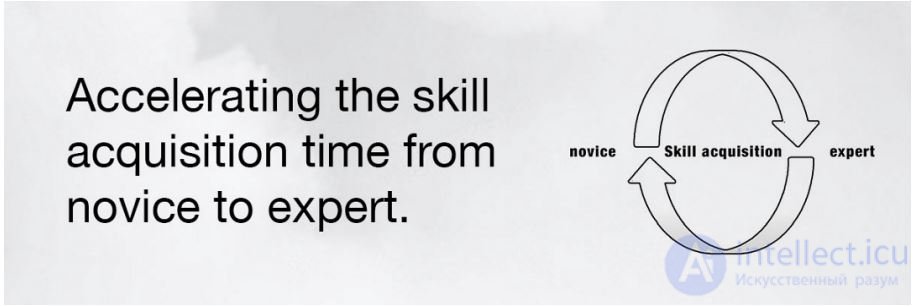

Systems of the second generation often impose restrictions on the creative process: management is rude, and interactions are insufficiently developed. Due to these limitations, popular tools (for example, the auto-complete function) have a controversial reputation. Now new technologies are coming from various research areas. It is hoped that they will help circumvent the previous limitations. We call these technologies the third generation assisted creativity systems (AC 3.0 - assisted creation 3.0). We are talking about designing systems that regulate the creative process through elaborate conversational interactions, expand creative abilities and accelerate the development of skills (that is, the transition from beginner to expert).

The principles of the assisted creativity of the third generation find practical application in solving an ever wider range of creative tasks. Here are some examples:

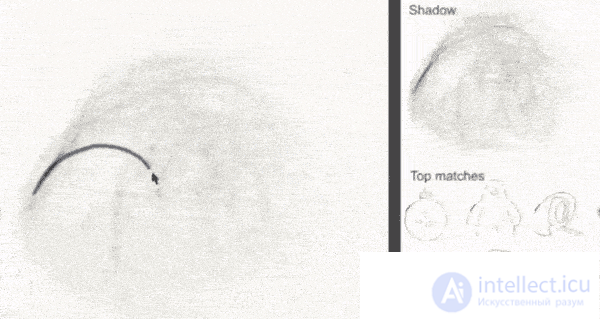

“Assisted drawing” helps illustrators to draw by adjusting strokes.

Assisted writing helps authors to write, improving the style of the text. “Assisted video” (assisted video) helps filmmakers edit videos, making it easy to cut out the extra.

Assisted music helps composers create music by proposing new ideas.

Assisted freehand drawing (2011)

It is difficult to show the full depth of the research with several examples: there are a lot of ideas and fields of study. To track the development of assisted creativity, we analyzed the latest scientific publications of many organizations with the help of machine learning, graph theory and visualization. Judging by the quantitative indicators (the number of publications and experiments), the study and application of assisted creativity leads among other creative disciplines. Interestingly, research on the subject of machine learning (ML - machine learning) and human-computer interaction (HCI - human-computer interaction) make a great contribution to the study of designing systems of assistive creativity. Together, these two disciplines provide a conceptual framework of artificial intelligence in the context of human interaction.

Already in 2011, Rebecca Ann Fibrink, a researcher of machine learning and human-computer interaction at Goldsmiths University, asked the relevant question: “Can we find the use of machine learning in such non-traditional areas as creativity, research?” [9]. In subsequent years, the Fibrink initiative was supported by representatives of various communities: today, many new ideas, theories, experiments, approaches and products are being studied and developed. Continuing studies of human-computer interaction and machine learning open up new opportunities and metaphors for designing systems of assisted creativity.

During the study of assisted creativity, we noticed a couple of current trends that may affect creativity: 1) Assisted creativity systems increase the availability of most creative skills 2) Collaborative platforms - such as Online Video and Open Source - facilitate the acquisition process new creative skills. Taken together, these trends accelerate the process of transforming a person from novice to expert. This causes an interesting phenomenon, which we called the “democratization of creativity”. Now we look at these trends in more detail.

Trend 1: creativity becomes available.

For a composer or photographer of the 1980s, a home studio was just a distant dream. Today in one click from us there are huge opportunities in a variety of creative directions. This gives beginners and experts a chance to show more creativity for a longer time. We can say that the price of creativity decreases. In the creative world, the most important difficulty has always been the “high entrance barrier” [10] for a person who does not possess special skills or talents. Today, systems of assisted creativity significantly reduce this “high barrier”, making creative processes more accessible and making it easier to learn

out skills.

Already in the 1960s, Engelbart reflected not only on empowering individuals, but also on strengthening the collective group mind and on optimizing teamwork and problem solving. As social networks and collaboration programs evolve, we begin to understand how technology can be used to enhance group self-organization, efficiency, and creativity. The bottom line is that creativity is a collective process that goes beyond technological tools, although it can be greatly enhanced through technology. To achieve development, the capabilities of the person and the capabilities of the machine need to be synchronized.

If you try to predict the development of these trends, you’ll get a scenario that we call “escalation of creativity”: a world in which creativity will be widely available, and anyone can write like Shakespeare, write music like Bach, paint pictures like Van Gogh, be a skillful designer and look for new forms of creative expression. For a person who does not possess any special creative abilities, the systems of assisted creativity open up many possibilities. If people have the opportunity to learn creative skills on demand, we will have to rethink such concepts as “expert” and “design”. As a result of this escalation, creativity will become one of the means of empathic communication.

And although such scenarios still seem fantastic, the very idea of the future democratization and escalation of creativity determines our current design decisions. Already, we face a difficult task: to create systems that can adapt to different cultural traditions, support different types of creativity, respond to a multitude of human needs and provide transparent feedback.

The first question to ask is when discussing democratization and the escalation of creativity: “Are we creating tools that will strengthen us, or autopilots that will replace us?” Such questions have been haunting humanity for 5,000 years, since how people began to use large cattle in agriculture [11]. History proves to us that any technology has its own dynamics and momentum. As Marshal McLuhan said: “At first we form technologies, and then technologies form us” [12]. Nevertheless, we do not consider technology as the main driving force of nature: human decisions and actions play a decisive role, and they are determined by culture, politics and power.

The second question you want to ask is: “what is meant by automation?”. Our current understanding of automation is strongly influenced by the ideas of the industrial revolution: the mass production of goods by machines. Of course, the problem of mass unemployment due to the replacement of human labor with machine labor is a serious matter, but nevertheless, automation also has advantages. Some activities should be given to machines - especially if they imply inhuman working conditions or a waste of human potential. If we consider automation from the point of view of human potential and capabilities: its strengths and weaknesses, needs and desires, it becomes clear that automation is a possibility rather than a threat.

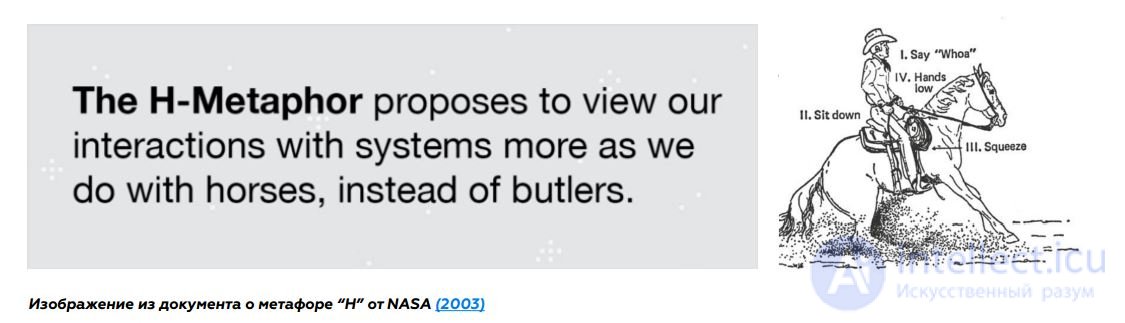

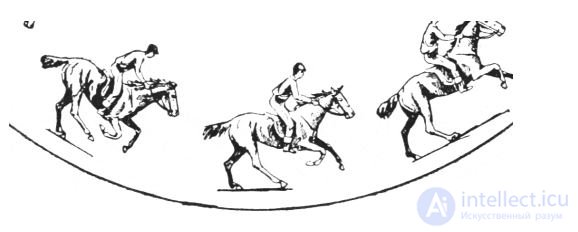

Strengthening (augmentation) and automation (automation) are two different things: automation promises to “free us from inhuman tasks”, and the goal of strengthening is to expand our capabilities. That is, it is supposed not to replace a person, but to expand the collective potential of society. To better understand this phenomenon, let us turn to the concept that NASA developed to study the issues of autonomy: the “H” metaphor [13]. This concept compares the interaction of man and system with the treatment of horses.

Imagine a rider on a horse: if the rider’s movements are precise and conscious, the horse exactly executes the commands. But it is necessary to give a more vague indication, and the horse will go beyond the usual patterns of behavior and take control. The ability to “loosen or tighten the reins” provides smooth feedback and constant monitoring. It works even better than standing rider teams and horse reactions. Human-computer interaction and machine learning researcher Roderick Murray-Smith suggests using the “H” metaphor in the context of interface development. He suggests: “The devices of the future will be able to sense much more surrounding signals, which will allow you to interact with them in many ways. Thanks to this, we can from time to time reduce control and interact more relaxedly ”[14].

When we can interact with systems more relaxed and sometimes reduce the level of control, human-computer interaction, as well as the joint work of people will take completely different forms. If the intuition of the person and the intellect of the machine begin to work in a pair - a completely new creative process will turn out, which neither the person nor the machine can repeat separately. Thanks to this, creativity will become more accessible, and the collective potential of mankind will increase significantly. And although you can imagine a lot of pessimistic scenarios for the development of this sphere, we intentionally concentrate on opportunities, and not on fears. Difficult ethical questions and concerns must become the ground for research and a call for collective decisions. Then the grim scenarios of the future can be avoided.

Comments

To leave a comment

machine art

Terms: machine art