Lecture

Antigames are a phenomenon or genre in video games that deliberately violate or reject traditional principles of game design. This may include the absence of a goal, the refusal to win/lose, unusual controls, minimalism, or even deliberately boring, unpleasant, absurd, or frustrating gameplay.

In short: anti-games are games that behave like non-games, but that is precisely their game essence.

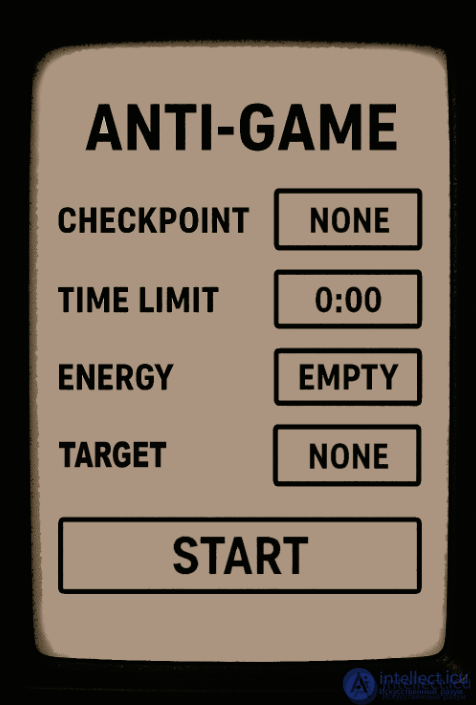

Fig. Interface of a typical anti-game

Lack of purpose or meaning (no "win")

Violation of player expectations from familiar games

Minimalistic or intentionally off-putting visuals

Mechanics that cause discomfort or boredom

Philosophical or critical orientation (irony over the industry, understanding the meaning of games)

"The Stanley Parable"

- Explores player choice and free will, subverting traditional notions of narrative.

"Desert Bus"

- 8 hour real time bus ride simulator without events. Created as a parody.

"Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy"

- Unforgiving controls, an absurd challenge, and the developer's philosophical musings.

Getting Over It revolves around a player-controlled character who is in a large metal cauldron and named Diogenes after the philosopher who lives in a pot. He wields a Yosemite hammer, which he can use to grab objects and move himself. Using a mouse or trackpad, the player attempts to move the man's upper body and the hammer to climb a steep mountain.

As the player progresses up the mountain, they are constantly at risk of losing some or all of their progress; there are no checkpoints. The game ends when the player reaches the highest point of the map, entering space. The closing credits gradually roll, and at the end, a message appears asking players if they are recording their gameplay. If the player indicates that they are not, the game provides access to a chat room filled with other players who have recently completed the game.

Getting Over It features a voiceover by Bennett Foddy, in which he discusses the philosophical observations he makes while climbing the mountain, as well as his own inspirations and experiences developing the game. Additionally, the commentary includes quotes regarding frustration and persistence when the player loses significant progress, as well as when the player reaches certain milestones in the game.

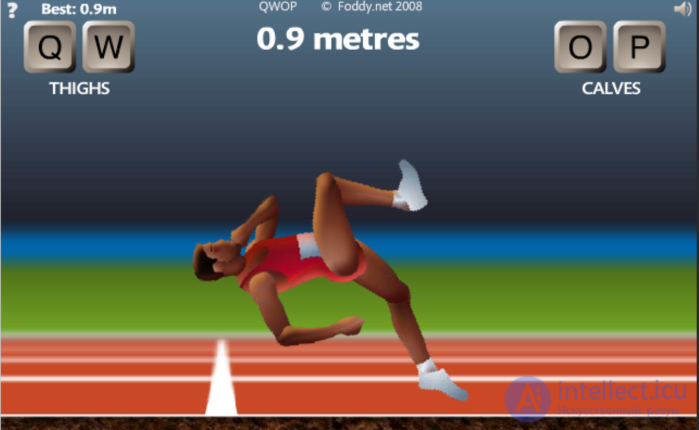

"QWOP"

- Controlling the athlete's legs with 4 keys is extremely unintuitive.

Players play as an athlete named "Qwop" who competes in the 100-meter dash at the Olympic Games. Using only the Q, W, O, and P keys, players must control the movement of the athlete's legs to move the character forward while trying to avoid falling. The Q and W keys each move one of the runner's thighs, while the O and P keys work with the runner's calves. The Q key moves the runner's right thigh forward and left thigh back, while the W key does the opposite. The O and P keys work the same as the Q and W keys, but with the runner's calves. The actual amount of movement of the joint depends on the resistance caused by the gravity and inertia forces applied to it.

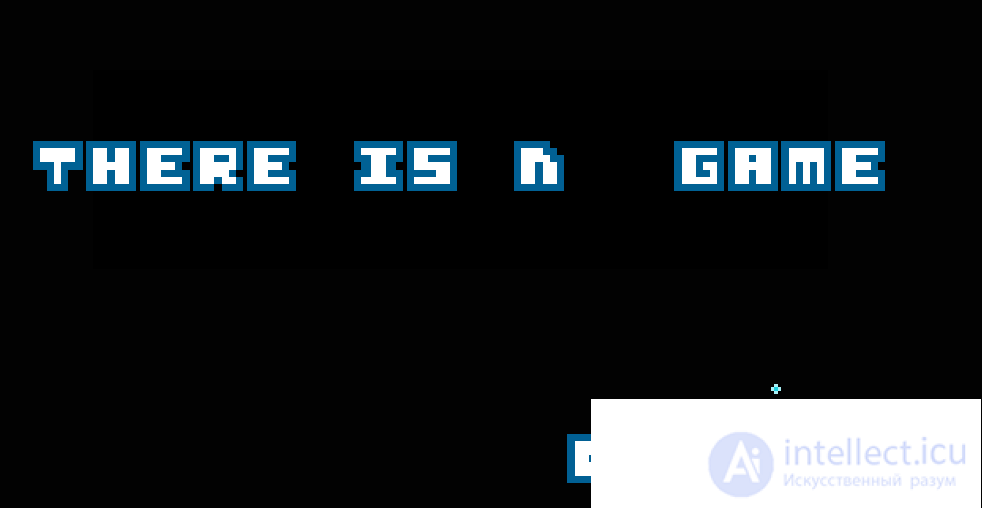

"There Is No Game"

- Declares that "there is no game" and in every way interferes with playing, although this is the essence of the gameplay.

Criticism of the gaming industry

Experiments with form and meaning

Art (analogous to conceptual art)

Challenging player expectations

Humor or satire

Antigames are a special movement in the world of video games that consciously reject the established principles of game design. They challenge player expectations, undermine industry standards, and often look like a paradox: “games that don’t want to be games.” While most projects strive to entertain, antigames provoke, irritate, and pose questions — and this is where their artistic and critical value lies.

One of the key functions of anti-games is open criticism of modern trends in the gaming industry: hyper-commerce, hackneyed mechanics, mindless gameplay, cloning of success formulas.

Anti-games often use irony as a tool. A classic example is "There Is No Game", a game that initially denies its existence. It ridicules the typical interface, template quests and the very idea that "a game should be a game". Behind the absurdity is hidden criticism of the predictability of many commercial projects.

In games like The Beginner's Guide or The Stanley Parable, developers dismantle the very structure of the narrative and mechanics. This is a kind of response to the industry, where the player is led down the corridor of the "illusion of choice." Antigames expose this mechanism, revealing its artificiality.

Many anti-games deliberately deprive the player of traditional satisfaction - upgrades, points, victories. In "Desert Bus" you drive along a straight road for 8 hours of real time without events. This is a mockery of "simulators" and endless grind mechanics, where the reward becomes an end in itself, having no meaning.

Through absurdity and discomfort, anti-games raise philosophical and social questions: “Why do we play?”, “What makes a game a game?”, “Are we repeating the same actions for empty rewards?” These games can be boring or annoying - and this is their function: to reflect the meaninglessness of many gaming habits cultivated by the industry.

Antigames are not just “weird” or “unplayable” projects. They are a whole movement in game art that deliberately breaks the rules in order to ask new questions about the very nature of the game. Instead of the usual victories, points, missions and levels — frustration, absurdity, emptiness, philosophy. One of the most important aspects of antigames is experimentation with form and meaning — an attempt to rethink what a game is, what it should look like and why it exists at all.

Anti-games question the very idea of gameplay. This is not just a rejection of traditional mechanics - it is a search for new forms that were not previously considered "gameable". And often, it is in these forms that unusual meanings are revealed that cannot be expressed through familiar genres.

In antigames, structure and control are often part of the message themselves. For example:

In QWOP, the sprinter controls are so absurdly complex that they evoke laughter, anger, and confusion rather than excitement. This destroys the idea of "the joy of mastery" by showing that control is not always a blessing.

Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy turns a mountain climb into a meditation on failure: each drop is a metaphor for human effort and repeated failure.

Thus, mechanics becomes not a tool of entertainment, but a language of meaning.

Antigames often break the linear narrative or abandon it entirely:

The Beginner's Guide is not a character story, but a story of a developer exploring his own creativity and the perception of players. A game without a goal, where the ending is not a denouement, but a question without an answer.

The Stanley Parable is a narrative deconstruction in which the narrator's voice conflicts with the player's choices, revealing the illusion of freedom.

This approach shows that a plot can be illogical, fragmentary, even meaningless if it serves reflection rather than entertainment.

Antigames are not just a unique style, they are often an antigenre:

In Desert Bus, the player doesn't compete, doesn't explore, doesn't interact. He just drives. It's not a racing game, it's a stagnation game, a parody of the very idea of "content."

Jason Rohrer's Gravitation turns gameplay into an emotional diary, where interactions with objects reflect feelings of loneliness, highs, and lows.

Here the boundaries between play, poetry and performance disappear.

Experimenting with form, anti-games approach contemporary art. Like gallery installations, they are not always “understandable,” but provoke feelings and thoughts. Some of them can be perceived as:

Interactive essays

Philosophical parables

Critical statement about culture

Antigame does not seek to please. It seeks to make you think, sometimes to shock or even to repel.

Antigames are a phenomenon in which the game form is used not so much for entertainment as for a statement. They deliberately destroy the principles of classical game design, depriving the player of goals, familiar rules and rewards. This destruction is a conscious gesture, close to what conceptual artists once accomplished in the 20th century. Antigames are not just games, but forms of media art that use interactivity to pose questions rather than provide answers.

Conceptual art puts the idea above aesthetics or technique. Antigames do the same: meaning is more important than gameplay. Sometimes the meaning is even the lack of it.

“This is not a game,” says There Is No Game, and yet it is this statement that becomes a game. Just as Marcel Duchamp’s urinal became art when it was placed in a gallery, the simplest code or action can become a game if given the appropriate context.

Antigames often lack graphics, music, interface, or make them deliberately repulsive. This repeats the gestures of minimalists, where the object is replaced by the viewer's attitude towards it.

Example:

Desert Bus is an 8-hour drive on a straight road with no events. It is not a simulator, but a real-time performance, where the act of “playing” itself becomes a meditative observation of emptiness.

In antigames, the gameplay ceases to be a means of achieving a goal. It becomes a metaphor, an analogue of an artistic device.

Example:

Everyday the Same Dream is a short game about an office worker stuck in a routine loop. The game repeats day after day until the player starts breaking the rules - a symbol of rejecting the ordinary. This is not gameplay for the sake of passing, but a visual poem.

As in conceptual art, the player's reaction is part of the work. Boredom, anger, misunderstanding, laughter - these are not mistakes, but planned elements.

The Beginner's Guide offers the player "a collection of games from another developer," but in reality it is an interactive confession of the author, a game with expectations, trust, and the boundary between art and man.

Anti-games are closer to art galleries than to Steam tops. They can often be imagined in a contemporary art museum next to a video installation or sound performance. Why?

They work with a concept, not a product.

They use the game as a medium, not a genre.

They require participation, like any postmodern art.

In modern game design, the player is the center of the universe: they are led by the hand, rewarded, entertained, and made comfortable. But anti-games run counter to this logic. They reject traditional patterns and challenge the player’s expectations, forcing them not to play but to reflect, endure, doubt, get angry, and rethink the very essence of video games.

Most players - even unconsciously - expect from the game:

Clear goal

Clear rules

Smooth increase in complexity

Feelings of progress

Rewards and pleasure

Feedback

This is what decades of design have shaped, from Mario to Witcher 3. Antigames sabotage these expectations, as if to say, “No, it won’t be like this.”

Antigames may not have a final goal at all. The player expects meaning - and gets meaninglessness.

Example:

"Desert Bus" - you drive 8 hours on a perfectly straight road. No enemies, no scenery, no dialogue. The player expects "gameplay" - but gets routine.

Instead of smooth control - discomfort. Instead of logic - absurdity.

Example:

"QWOP" - you control the runner's legs with four keys, and everything falls apart. The player expects smooth control - gets humiliated.

The player is accustomed to "choice". Antigames reveal that this choice is often a fiction.

Example:

"The Stanley Parable" - you think you choose the path. But the narrator knows all your actions. Your "freedom" is a plot device, not freedom.

Instead of pleasure - frustration. Progress - but at the expense of suffering.

Example:

"Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy" - each fall can cancel hours of play. The player expects a reward for his efforts - gets a test of patience.

When a game breaks expectations, it takes the player out of automatism. Instead of the usual “pass and get it,” an internal dialogue begins:

"Why do I want to go through this?"

"What do I expect from the game in general?"

"Where is the line between play and absurdity?"

Anti-game works like a mirror: it shows how strongly we are programmed for pleasure, control and meaning – even in a virtual environment.

In antigames, the player is not a hero, but a test subject. His reactions, patience, and thinking become the center of the game experiment.

The player is deprived of support. He becomes vulnerable. And in this vulnerable state new meanings arise that would be impossible to convey through traditional gameplay.

Antigames aren't just weird, absurd, or "broken" video games. They're artistic statements that use gameplay as a language of criticism, philosophy, or... humor. One of the most recognizable forms of antigames is humorous satire — when a game doesn't directly entertain, but ridicules the very concept of a game, game design, player culture, or industry.

If regular games use humor as a way to "amuse" the player, antigames use humor as a tool to undermine. Their laughter is not a joke for the sake of laughter, but a commentary. Often caustic, absurd, rude - but to the point.

A game that... has no game.

Behind the narrator's voice is a witty commentary on how formulaic modern quests and interactions are.

A satire on intrusive tutorials, hidden scripts and the "illusion of choice".

The player is given the illusion of freedom, but the narrator knows everything in advance.

The humor here is in the absurdity of the narrative: the game laughs at the player, who is used to being the center of the universe.

It's a satire on narrative games, on the "branching plot" and even on the very concept of game design as managing player behavior.

It's impossible to control a runner - and that's the joke.

The game ridicules the idea of "realistic physics" by turning it into a farce and a circus.

Laughter is born from the player's suffering, but this suffering is intentional. It's a satire on sports simulators.

While it's not exactly an anti-game, it does employ grotesquery and parody: you "work" in a world where robots try to imitate outdated professions.

It’s a mockery of office routine and, at the same time, of VR itself as a serious technology.

Antigames with humor do not try to be funny for the sake of laughing. Their irony works according to the same laws as in literature or cinema:

Overexploitation of mechanics to the point of absurdity

Inconsistency between form and content

Self-irony - the game makes fun of itself

Breaking the fourth wall, making fun of the player and his habits

In such games, humor works to rethink interaction. Why do we laugh when everything goes wrong? Why do we laugh when the game "breaks"? These reactions become the basis for a new gaming experience - the game as a satirical performance.

Antigames are not mistakes or failures, but conscious acts of resistance. They do not entertain, but make you think; they do not follow the rules, but break them. In an era when games often become products, antigames are a reminder: a game can be a statement. Even an annoying one.

Antigames are experiments not for the sake of strangeness, but for the sake of new meanings. They abandon the familiar guise to speak to the player on a different level: about creativity, freedom, frustration, meaninglessness, and hope. In a world where millions of games repeat the same formulas, antigames remind us that a game can be anything – even a challenge to the very idea of a game.

Antigames are games that speak the language of art. They don’t want to be convenient, beautiful, or fun. They want to be thoughtful. Like conceptual art, they appeal not to the eye, but to the mind. They don’t give rewards – they create questions. And that’s their power.

Anti-games are a challenge, a provocation, a "grain of sand in the shoe" of the entertainment industry. By breaking the player's expectations, they expose cliches, expose dependencies on rewards, and force us to take a new look at games - as media, as art, as personal experience.

These are not "versus player" games. These are games that require maturity, self-irony, and a willingness to be surprised - even unpleasantly - from the player.

Antigames with humor are not just “funny games.” They are satirical performances where the object of the joke is the gaming culture itself, its templates, cliches, and players. Laughter in such projects is a way to look at games differently. Sometimes it sounds funny, sometimes nervous, sometimes bitter. But it is always meaningful.

Comments

To leave a comment

Computer games developming, game-design

Terms: Computer games developming, game-design